Chapter 19 Bladder Cancer and Upper Tracts

Epidemiology And Risk Factors

Epidemiology

Bladder cancer is the most common tumor of the urinary tract. In the United States, it is the fourth most common malignancy in males, accounting for 7% of all male malignancies. There will be an estimated 70,530 new cases and 14,680 deaths from bladder cancer in the United States in 2010.1 The peak incidence is in the ninth decade, although there is a suggestion of a trend toward presentations at a younger age. The incidence is four times higher in men than in women. The lifetime risk for men is 3.8% and for women is 1.2%.1 The tumor is twice as common in whites as in African Americans. In the United Kingdom, bladder cancer is overall the seventh most common malignancy, with an age-standardized rate of 11.4 per 100,000.2

The incidence of upper tract disease is less easily estimated because cancer registries tend to include primary PC system tumors as “renal” cancers. If one makes the assumption that 15% of such “renal” tumors are of PC system origin, there will be 8740 new cases and 1960 deaths from renal pelvic cancer in the USA in 2010.1 There will be an estimated 2490 new cases and 830 deaths from ureteric cancer in the United States in 2010.1 Ureteral transitional cell cancer (TCC), like bladder cancer, is more common in men than in women (ratio 2:1), and the incidence peaks in the eighth decade of life.

For patients with a bladder cancer, up to 6.4% will develop upper tract tumors.3,4 Conversely, for patients with upper tract tumors, up to 40% will develop lower tract disease.5

Risk Factors

Reported risk factors for urothelial tumors include exposure to aniline, aromatic amines, diesel fumes, phenacetin abuse, cigarette smoking, arsenic, and living in urban areas. Heavy smokers (>40 pack-yr) are five times more prone to develop TCC than nonsmokers.6 Balkan nephropathy, an endemic degenerative interstitial nephropathy in Eastern Europe of unknown etiology, is associated with 100 to 200 times the risk of upper tract TCC. These tumors are typical multifocal, but of low grade.7,8 Coffee drinking and artificial sweeteners have been considered to be possible risk factors, but these have not been fully substantiated as a cause of this malignancy.9

Genetic factors in the etiology of urothelial tumors are emerging, and these may be associated with the aggressiveness of the tumor, such as tumor grade, stage, and propensity for vascular invasion.10

Adenocarcinomas of the bladder mucosa are associated with a persistent urachal remnant and cystitis glandularis (which is associated with bladder extrophy).11 In addition, micropapillary and small cell tumors have been reported and are signs of an aggressive histology associated with worse outcomes, likely as a result of early micrometastases.12,13 The rarity of these two histologies has limited our abilities to determine definitive associations; their frequent finding in combination with TCCs would lead one to expect an association with carcinogen exposure.

Anatomy and Pathology

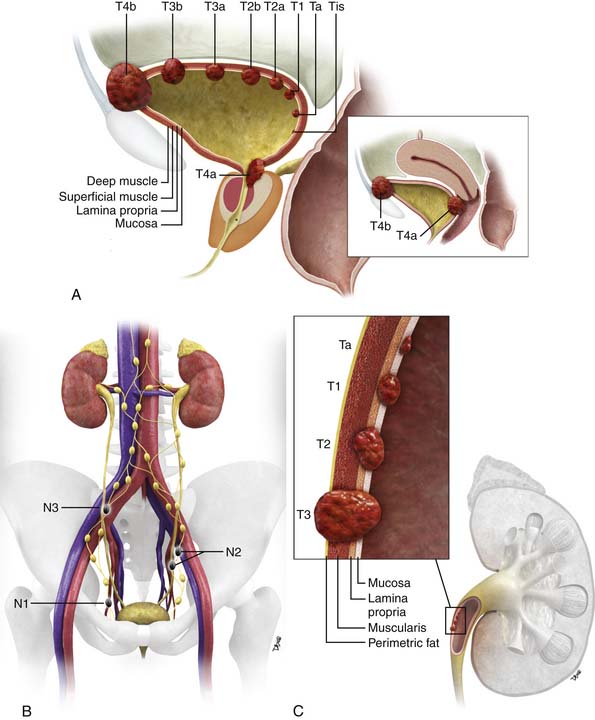

The urinary collecting system conveys, stores, and delivers urine to the exterior of the body; it extends from the renal collecting system and calyces, renal pelvis, ureter, bladder, and urethra. The epithelium of the entire collecting system, the urothelium, consists of the same cell type, transition cells. Deep to the urothelium is a layer of connective tissue and irregularly arranged smooth muscle fibers, frequently considered the submucosa (although strictly this term is incorrect because there is no muscularis mucosae). Deep to the submucosa are three layers of muscle (internal or superficial longitudinal, middle circular, and external or deep longitudinal). Deep to all of these layers is the perivesical or periureteral fat or, toward the dome of the bladder, a partial serous coat derived from the peritoneum (Figure 19-1A).

Figure 19-1 Bladder staging. Schematic of T stage (A) and N stage (B). C, Upper tract staging: schematic of T stage.

The vast majority of tumors that affect the urinary collecting system are epithelial in origin and are termed urothelial carcinomas. The vast majority of these tumors are of TCC origin (>90%); other subtypes are squamous cell (5-10%), adenocarcinoma (2-3%), and small cell carcinoma (<1%).11 TCCs have a propensity to develop in multiple locations throughout the urothelium, both upper tracts and lower tracts. Adenocarcinomas may be mucin-secreting.

Other extremely rare tumors include leiomyoma, hemangioma, granular cell tumors, neurofibroma, paraganglioma, pheochromocytoma, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, hematopoietic and lymphoid tumors (e.g., non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma), carcinosarcoma, malignant melanoma, metastases, and direct invasion from adjacent organs.11

Bladder

The majority of superficial tumors, which are limited to the mucosa and lamina propria, tend to be papillary (i.e., projecting into the lumen) and of low histologic grade. They tend to carry a good prognosis, although they have a propensity to recur (70% at 3 yr), and 10% to 20% may progress to invasive disease (although this is as high as 46% in patients with T1 disease).14 Seventy percent of patients with superficial tumors have low-grade papillary tumors, and 30% have higher-grade, flat, carcinomas in situ. Flat carcinomas in situ carry a higher risk of progression and invasion.15

Upper Tracts

In the ureter, the frequency distribution of urothelial tumors is distal (73%), mid (24%), and proximal (3%). Bilateral disease may occur in 2% to 5% of cases. The tumors are histologically similar to those in the bladder.16 As with urothelial tumors in the bladder, upper tract tumors may be superficial (85%) or infiltrating (15%).

Key Points Anatomy and pathology

• The whole of the urinary collecting system is lined by urothelium.

• The “upper” urinary collecting tract is considered to be calyces, renal pelvis, and ureter; the “lower tract,” bladder and urethra.

• The whole urothelium is potentially at risk of tumor once a tumor is found in any location.

• Most common urothelial tumor is TCC (>90%).

• Urothelial tumors may be superficial (70%) or infiltrative (30%).

• Infiltrative tumors are generally of higher histologic grade and more aggressive.

Patterns of Tumor Spread

Bladder

Disease may spread lymphatically, typically in a contiguous fashion from pelvic (internal iliac, obturator, and external iliac) to common iliac and retroperitoneal nodes. In advanced disease, lymphatic spread may extend above the diaphragm to mediastinal, hilar, and cervical nodes. The incidence of nodal metastasis is approximately 30% in tumors that involve the bladder wall and approximately 60% in those with extravesical invasion.17 Nodal staging has an important impact on prognosis.

The tumor may also metastasize hematogenously, with the liver being the most common site for metastatic disease, followed by bones and lungs.18

When seen, in males, TCC of the urethra is commonly found in the prostatic urethra.

Upper Tracts

Primary urothelial tumors in the upper tracts spread locally to involve periureteral and peripelvic fat. In the region of the renal pelvis, urothelial tumors can infiltrate into the renal parenchyma, where unlike primary renal tumors, they tend to preserve the contour of the kidney. Infiltrating tumors of the ureters tend to be more aggressive than those in the bladder, probably because of the thinner wall of the ureter.19,20

Staging Evaluation

Bladder

The two main staging classification systems for tumors are (1) the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM; Tables 19-1 and 19-2) and (2) the Jewett-Strong-Marshall classification (Table 19-3). The TNM staging system is the more widely used and comprehensive. T stage mainly describes the depth of local bladder wall invasion of the tumor as related to normal bladder wall layers. N stage is based on the size and number of nodes involved by metastatic disease. M stage describes whether there are disseminated hematogenous metastases or not. Retroperitoneal adenopathy is classified as M stage disease.

Table 19-1 Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging for Bladder Cancer by the American Joint Committee on Cancer

| STAGE | DISEASE EXTENT |

|---|---|

| T Stage | |

| Ta | Noninvasive papillary carcinoma, confined to urothelium and projecting toward lumen |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ: flat tumor, high-grade histologic features confined to urothelium |

| T1 | Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue (lamina propria) |

| T2 | Tumor invades muscle |

| T2a | Tumor invades superficial muscle (inner half) |

| T2b | Tumor invades deep muscle (outer half) |

| T3 | Tumor invades perivesical tissue |

| T3a | Tumor invades perivesical tissue microscopically |

| T3b | Tumor invades perivesical tissue macroscopically (extravesical mass) |

| T4 | Tumor invades prostate, uterus, vagina, pelvic wall, or abdominal wall |

| T4a | Tumor invades prostate, uterus, or vagina |

| T4b | Tumor invades pelvic wall or abdominal wall |

| N Stage | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastases |

| N1 | Metastasis to single lymph node < 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2 | Metastasis to single lymph node 2-5 cm in greatest dimension or multiple lymph nodes none > 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node > 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| M Stage | |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

Suffix “is,” associated carcinoma in situ; suffix “m,” multiple tumors.

From Bladder cancer. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:569-577.

Table 19-2 Staging for Bladder Cancer, with Tumor-Node-Metastasis Equivalent

| STAGE | DISEASE EXTENT | TNM CLOSEST EQUIVALENT |

|---|---|---|

| 0a | Papillary, noninvasive | Ta, N0, M0 |

| 0is | Carcinoma in situ, noninvasive | Tis, N0, M0 |

| I | Invades subepithelial connective tissue | T1, N0, M0 |

| II | Invades muscle layer | T2, N0, M0 |

| III | Extravesical spread | T3 or T4a, N0, M0 |

| IV | Fixed to or invading prostate, uterus, vagina or pelvic lymph nodes | T4b, N0, M0 or any T, N1 to 3, M0, or any T, any N, M1 |

TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

From Bladder cancer. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:569-577.

Table 19-3 Comparison of AJCC and Jewett-Strong-Marshall Staging Systems

| STAGE | DISEASE EXTENT | TNM CLOSEST EQUIVALENT |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Limited to mucosa, flat in situ or papillary | Tis, Ta |

| A | Lamina propria invaded | T1 |

| B1 | < halfway through muscularis | T2a |

| B2 | > halfway through muscularis | T2b |

| C | Perivesical fat, prostate, uterus or vagina, pelvic wall or abdominal wall | T3, T4a, T4b |

| D1 | Pelvic lymph node(s) involved | N1-N3 |

| D2 | Distant metastases | M1 |

TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

From National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER Training Modules Staging: Comparison of AJCC & Jewell-Strong-Marshall Staging Systems. Available at http://training.seer.cancer.gov/bladder/abstract-code-staging.html (accessed October 27, 2011).

A schematic of the TNM T staging is presented in Figure 19-1A and B. Superficial tumors are considered Tis, Ta, and T1; infiltrative tumors are T2, T3, and T4.21,22

Prognosis worsens with increasing T, N, and M stage and higher classes of Jewett-Strong-Marshall staging. The overall 5-year survival is 97.2%, 74.3%, 36.2%, and 5.8%, for in situ, localized, regional, and distant disease, respectively.23 Nodal status and organ confinement are independent predictors of survival.24

Prognosis is also affected by tumor grade, the presence of vascular and lymphatic invasion, and diffuse carcinoma in situ (CIS). Of note, these latter factors are not currently reflected in staging classifications.25

Treatment options are influenced by tumor stage. Clinical staging can underestimate the extent of disease in up to 50% of cases as compared with pathology.25 Imaging has the potential to improve this.

Upper Tracts

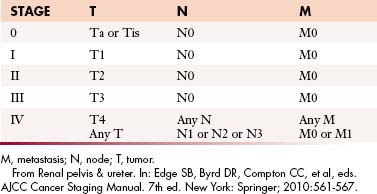

The TNM staging system for urothelial tumors of the upper tracts is presented in Tables 19-4 and 19-5. As with bladder staging, T staging of the upper tracts is assessed in

Table 19-4 Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging of Upper Urinary Tract Transitional Cell Carcinoma

| TNM STAGE | DISEASE EXTENT |

|---|---|

| Ta | Noninvasive papillary carcinoma, confined to urothelium and projecting toward lumen |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ: flat tumor, high-grade histologic features but confined to urothelium |

| T1 | Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue (lamina propria) |

| T2 | Tumor invades muscularis |

| T3 | Renal pelvis: Tumor invades beyond muscularis into peripelvic fat or renal parenchyma. Ureter: Tumor invades beyond muscularis into periureteric fat |

| T4 | Tumor invades adjacent organs, pelvic or abdominal wall, or through kidney into perinephric fat |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastases |

| N1 | Metastasis to single lymph node < 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2 | Metastasis to single lymph node 2-5 cm in greatest dimension, or multiple lymph nodes, none > 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node > 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

From Renal pelvis & ureter. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:561-567.

relation to depth of invasion into the various layers of the wall of the ureter (see Figure 19-1C).

Imaging

Primary Tumor (T)

Bladder

In low T stage disease, cystoscopy and deep biopsy with histologic evaluation is the standard of care. For more deeply invasive tumors (stage T3, T4), clinical staging, which includes bimanual examination under anesthesia to assess the bladder mass and fixity to adjacent organ, has reported errors of both under- and overstaging, of 25% to 50%.26–29 Imaging plays a role in the evaluation of such tumors, especially for nodal and hematogenous metastatic disease.

Computed Tomography

Technique

Thin-section rapid scanning in the portal venous phase at 60 to 80 seconds after commencement of intravenous (IV) contrast medium (125-150 mL at 2.5-3.0 mL/sec) allows detection of tumor enhancement in the bladder wall before excreted IV contrast medium reaches the bladder. Delayed images (180 sec) allow detection of soft tissue density masses against the background of IV contrast within the bladder lumen. Thin-section acquisition allows multiplanar re-formations. Oral and rectal contrast media assist in delineation of adjacent organs in the pelvis. The bladder should be moderately distended. Care should be taken not to over- or underdistend the bladder because the former may flatten small tumors and underdistention may result in spurious bladder wall thickening. If a urinary catheter is in place, it should be clamped for a period before and during the examination.

Findings

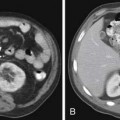

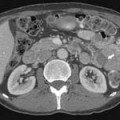

Urothelial tumors in the bladder may appear as foci of thickening in the wall or as filling defects, which may be polypodial (Figure 19-2). Fine calcification may be seen on the mucosal surface. The lesions may demonstrate early enhancement after IV contrast media infusion, probably a reflection of angiogenic activity in the tumor (Figure 19-3). CT is unable to resolve the various bladder wall layers and is, therefore, unable to resolve low T stage disease. Retraction of the outer bladder wall at the site of the tumor is suggestive of deep muscle involvement (stage T2b).

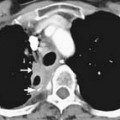

Tumors close to the vesicoureteric junction may cause ureteric obstruction, which may be a presenting feature of the disease (Figure 19-4). Tumors may also be detected in bladder diverticulae, which importantly may not be visible on cystoscopy (Figure 19-5).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Findings

The signs of bladder tumors are similar to those on CT. Tumors are usually hyperintense to muscle on T2-weighted images and isointense to muscle on T1-weighted images (Figure 19-6A). On occasion, the combination of T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced T1 weighted images can help to delineate between stages T2a and T2b tumors, with preservation of T2-weighted hypointensity of bladder muscle adjacent to enhancing tumor.

The corresponding findings of T3b disease described previously for CT appear as hypointense nodules or stranding within the T1-weighted and T2-weighted hyperintense perivesical fat (see Figure 19-6A). These findings may be more conspicuous with the use of contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fat-suppressed images, in which enhancing tissue is seen in the surrounding hypointense (suppressed) perivesical fat.30

MRI is superior to CT in staging T4 disease because of its better intrinsic contrast resolution and multiplanar capability. For example, the combination of sagittal and axial images on MRI allows good delineation of the rectum and vagina (see Figure 19-6B). It should be noted that abutment of structures does not necessarily indicate invasion, and conversely, involvement cannot be excluded; invasion is more likely if foci of infiltration can be identified.

Overall, studies of CT and MRI suggest that MRI is more accurate in staging with accuracies ranging from 73% to 96% compared with CT accuracies of 40% to 95%. This is largely because of the superior ability of MRI in assessing deep muscle layer involvement and earlier detection of adjacent organ invasion. It should be noted that most reported MRI evaluations have been undertaken with body and not pelvic phase array coils, and MRI accuracy may be improved further with such higher-resolution coils.17,31–49

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree