Gary P. Siskin • Tara Murray • Marcelo Guimaraes

PRINCIPLES OF EMBOLIZATION THERAPY

Embolization is defined as the intentional endovascular occlusion of an artery or vein.1 Presently, this procedure has been applied to almost every organ of the body for various indications. The procedure is performed by percutaneously delivering embolic agents into a target vascular system either through selective catheterization or direct puncture of the target organ/vessel. The correct use of embolization techniques require an in-depth knowledge of the clinical condition being treated, the available and appropriate embolic agents and delivery systems (catheters, microcatheters, and guiding catheters), the anticipated postprocedure patient care, and the potential complications of the procedure.

As a general rule for the practice of any percutaneous interventional therapy, every clinical situation must be thoroughly reviewed to help determine how and when to proceed with the embolization procedure. Review of any available imaging is paramount to plan the procedure approach and technique to be used. In general, an embolization procedure should be able to resolve the clinical problem in a single procedure because repeat procedures may not be possible. This is often the case in emergency situations, when alternatives may be limited and rapid decisions need to be made to use embolic therapy sooner rather than later. Ultimately, the final decision to perform an embolization procedure lies with the physician responsible for performing the procedure after an appropriate risk–benefit analysis has been made.

HISTORY

From a historical perspective, the initial agents used for embolization and the procedural indications have significantly changed over time.

The concept of therapeutic vascular occlusion actually began in 1933 when Hamby and Gardener treated a carotid cavernous fistula at surgery by embolizing the fistula with small fragments of muscle via arteriotomy.2 Doppman and Newton have been credited with performing the first percutaneous therapeutic embolization procedures.3,4 In 1968, these early interventionalists published separate case reports describing their independent experience with percutaneous embolization of spinal cord arteriovenous malformations. Doppman et al.3 used 3-mm stainless steel pellets for embolization, and Newton and Adams4 used lead pellets and small fragments of muscle.

In the early 1970s, experience with peripheral embolization was initially gained as a treatment option for acute gastrointestinal bleeding.5 During that time, the indications expanded into the treatment of gastroesophageal varices, arteriovenous fistulas and malformations, control of hemoptysis, treatment of varicocele, and ablation of tumors or organs.6 Initially, autologous clot was used as the embolic agent for these indications, but other agents were introduced during this time. The use of gelfoam for endovascular occlusion grew in popularity but was actually first reported as an embolic agent by Speakman7 in 1964. In 1974, Tadavarthy et al.8 reported the first use of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) as an embolic agent, and Serbinenko9 reported on the use of detachable balloons to treat intracerebral aneurysms. In 1975, Gianturco et al.10 reported on the development and use of the first coils: the cotton-tail device consisting of eight cotton threads attached to a 3-mm body of steel and the wool-tail device consisting of four wool fibers attached to a 5-cm length of guidewire. The wool-tail device design eventually transformed into the stainless steel coil in 1976, and in time, the thrombogenic wool fibers were replaced with nonantigenic synthetic fibers.11

Since that time, the basic tools of embolization have undergone significant development and improvement. New coil configurations, including detachable coils and vascular plugs, have been developed to increase the safety and effectiveness of coil embolization for both neurovascular and peripheral vascular applications.12,13 In addition, experience grew with liquid embolic agents such as cyanoacrylate and Onyx (Covidien, Irvine, California).14 For years, irregularly shaped PVA particles have been the particulate agent of choice. With the maturation of procedures such as chemoembolization and uterine fibroid embolization, new particulate agents were developed, including spherical embolic agents,15 drug-eluting beads,16 yttrium 90 microspheres,17 and soon, bioresorbable spheres.18,19

CLASSIFICATION OF EMBOLIC AGENTS

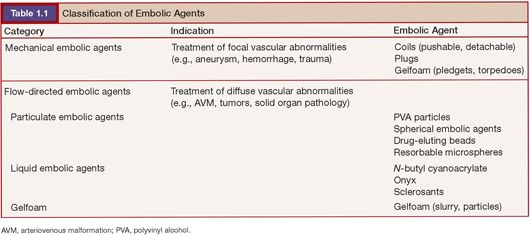

When looking at all of the available agents for embolization, it is often helpful to classify these agents from a clinical perspective, allowing a particular class or type of embolic agent to be an option for a specific indication or procedure. However, this is easier said than done because it can be difficult to define the terms that are traditionally used for this type of classification system. In addition, there is a significant amount of potential overlap between agents in different categories.

Historically, embolic materials have been grouped in several ways: by physical characteristics (type of material), longevity of vascular occlusion (temporary or permanent), level of occlusion (proximal or distal), pathology being treated, type of delivery technique, cost, and many other alternatives. When attempting to classify these materials clinically, consider that not all materials are available in every angiography suite due to local supply constraints and cost concerns or to marketing and regulatory issues. The availability of various embolic agents to allow for the appropriate performance of embolization procedures for various indications is a requirement for any interventionalist and hospital offering this service.

Traditional Classification System

The most common way to classify embolic agents has been to define them as being either temporary or permanent.1 This is helpful when selecting an embolic agent because some applications of embolization, such as trauma, may only require the use of a temporary agent, whereas in other applications, a permanent agent may be more appropriate. When this system is used, the temporary category is small and consists of only gelfoam, collagen, thrombin, and new biodegradable microspheres that are being developed but are not commercially available at this time.18,19 The remaining available agents are considered to be permanent.

When using this classification system, however, the question needs to be asked regarding what one is referring to when using the terms temporary and permanent. This classification system refers to temporary and permanent as terms used to describe the biodegradability of the actual embolic agent. It does not refer to the occlusion caused by the embolic agent because if it does, the group assignment might change for several agents. This can be exemplified with PVA particles. These particles have been classically described as permanent because they are not biodegradable and can be found in embolized tissue years after embolization.20 However, the occlusion caused by PVA particles is not always permanent. Recanalization has been demonstrated, with proposed mechanisms including angiogenesis and capillary regrowth caused by vascular proliferation inside organized thrombus and resorption of the thrombus in between PVA particles found in the vessel lumen after resolution of the initial inflammatory response.21–24 Similarly, gelatin sponge particles are considered to be a temporary embolic agent.25 This has historically been based on the work of Light and Prentice26 in 1945. Later studies have demonstrated the temporary nature of the occlusion induced by gelfoam,27,28 supporting its classification as a temporary embolic agent. However, permanent occlusion after gelfoam embolization has also been described and attributed to dense packing29 and to fibrotic or necrotic changes induced by the gelfoam.30,31 These examples demonstrate the difficulty in using the “temporary versus permanent” classification system unless a clear distinction is made between the temporary and permanent nature of the embolic agent or of the vascular occlusion induced by the embolic agent.

Classification of embolic agents based on the size of the vessel being embolized has also been described.32,33 Although this system can be useful in guiding interventionalists toward the use of appropriate agents, it becomes clear that overlap can exist between these categories. For example, coils are available in various sizes, making them appropriate to use for certain indications in both large and small vessels.

Present Classification System

Various pathologies are treated today by embolization. In general, these can be divided into focal abnormalities (i.e., aneurysms, traumatic injury, arteriovenous fistulae) and more diffuse abnormalities that are treating abnormal vascular beds in part or in their entirety. Focal abnormalities are typically treated by the insertion of mechanical embolic agents at or in close proximity to the abnormality being treated. Diffuse abnormalities, such as tumors and vascular malformations, are typically treated by placing a catheter proximal to the abnormal vascular bed and using a flow-directed embolic agent to embolize the abnormal vasculature. Therefore, it seems useful to classify agents as either mechanical (delivered at the site of a focal vascular abnormality) or flow-directed (delivered by flow from a catheter position proximal to a vascular abnormality (Table 1.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree