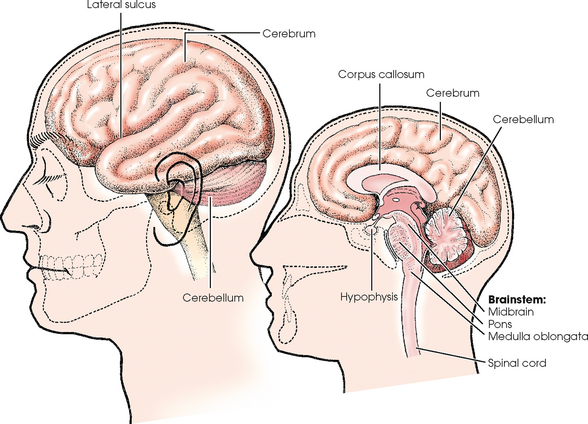

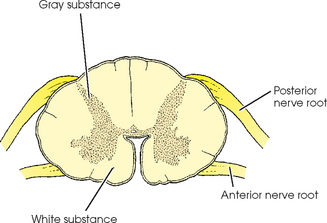

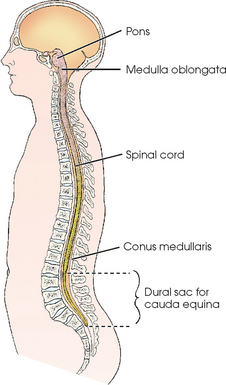

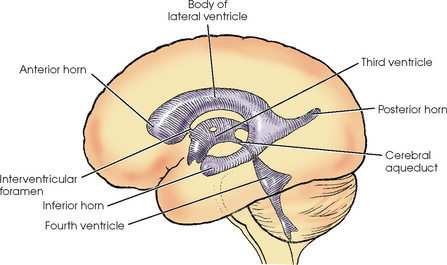

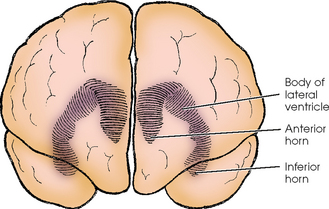

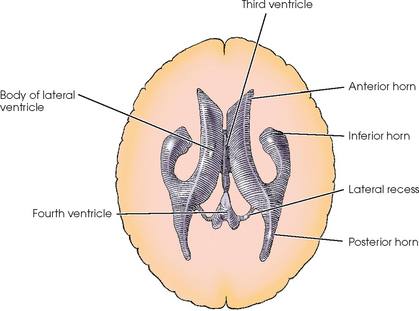

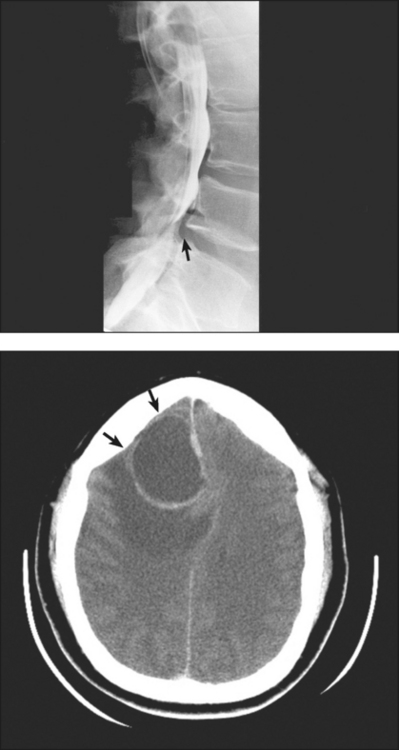

24 For descriptive purposes, the central nervous system (CNS) is divided into two parts: (1) the brain,* which occupies the cranial cavity, and (2) the spinal cord, which is suspended within the vertebral canal. The brain is composed of an outer portion of gray matter called the cortex and an inner portion of white matter. The brain consists of the cerebrum; cerebellum; and brainstem, which is continuous with the spinal cord (Fig. 24-1). The brainstem consists of the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata. The spinal cord is a slender, elongated structure consisting of an inner, gray, cellular substance, which has an H shape on transverse section, and an outer, white, fibrous substance (Figs. 24-2 and 24-3). The cord extends from the brain, where it is connected to the medulla oblongata at the level of the foramen magnum, to the approximate level of the space between the first and second lumbar vertebrae. The spinal cord ends in a pointed extremity called the conus medullaris (see Fig. 24-3). The filum terminale is a delicate fibrous strand that extends from the terminal tip and attaches the cord to the upper coccygeal segment. The ventricular system of the brain consists of four irregular, fluid-containing cavities that communicate with one another through connecting channels (Figs. 24-4 to 24-6). The two upper cavities are an identical pair and are called the right and left lateral ventricles. They are situated, one on each side of the midsagittal plane, in the inferior medial part of the corresponding hemisphere of the cerebrum. Tomography may be used to supplement images of the spine for initial screening purposes. Tomography has been largely replaced by computed tomography (CT) in many institutions (see Chapter 31). Tomography may be employed to show long continuous areas of the spine. Disadvantages of tomography include the lack of soft tissue detail and the difficulty in positioning a traumatized patient for lateral tomographic radiographs. Most myelograms are performed on an outpatient basis, with patients recovering for approximately 4 to 8 hours after the procedure before being released to return home. In many parts of the United States, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (see Chapter 32) has largely replaced myelography. Myelography continues to be the preferred examination method for assessing disk disease in patients with contraindications to MRI, such as pacemakers or metallic posterior spinal fusion rods. A non–water-soluble, iodinated ester (iophendylate [Pantopaque]) was introduced in 1942. Because it could not be absorbed by the body, this lipid-based contrast medium required removal after the procedure. Frequently, some contrast remained in the canal and could be seen on noncontrast radiographs of patients who had the myelography procedure before the introduction of the newer medium. Iophendylate was used in myelography for many years, but is no longer commercially available. The first water-soluble, nonionic, iodinated contrast agent, metrizamide, was introduced in the late 1970s. Thereafter, water-soluble contrast media quickly became the agents of choice. Nonionic, water-soluble contrast media provide good visualization of nerve roots (Fig. 24-7

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

ANATOMY

Brain

Spinal Cord

Ventricular System

Plain Radiographic Examination

Myelography

CONTRAST MEDIA

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM