Fig. 9.1

Expansive solid lesion of the descending colon with free small air bubbles near the lesion (arrow) and pneumoperitoneum (curved arrow)

Fig. 9.2

Modest quote of pneumoperitoneum between intestinal loops and below the diaphragm (arrows)

9.8 Colonic Ischemia and Stercoral Perforation

Stercoral perforation is related to a localized mucosal ulceration and ischemic pressure necrosis of the bowel wall for vascular occlusion, caused by a stercoraceous mass, most often involving the sigmoid or rectosigmoid.

Risk factors include conditions leading to longstanding constipation, often in bedridden patients, such as drug-induced constipation (narcotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, postoperative analgesia, and methadone), scleroderma, and an underlying obstructing colonic lesion such as neoplasm or stricture [15].

The most useful tool for diagnosis of stercoral perforation is abdominopelvic CT [16]. The main specific CT finding of vascular impairment of the colonic wall (ischemia) is lack or poor enhancement of its wall and often, in relation to focal fecal distension of the colonic lumen, is indicative of stercoral perforation (Fig. 9.3) [8]. Other CT findings are free intraperitoneal air (Fig. 9.4), colonic mural thickening, and adjacent fat stranding [17].

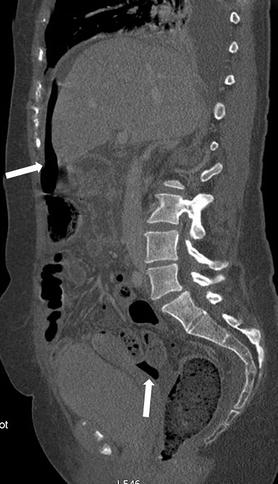

Fig. 9.3

Stercoraceous mass of rectal-sigma (curved arrow) and lack of wall contrast enhancement (arrows)

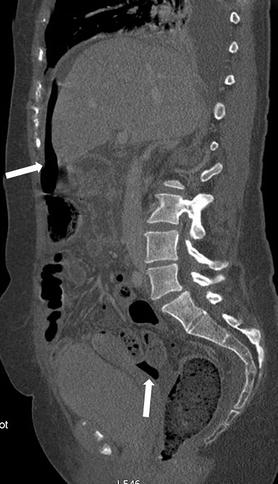

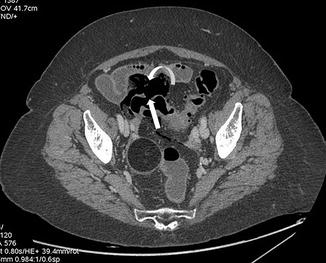

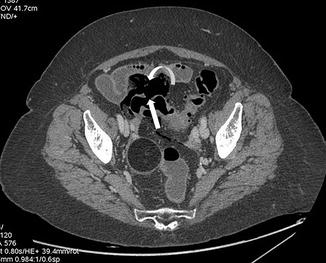

Fig. 9.4

Supramesecolic and undermesocolic free intraperitoneal air (arrows)

9.9 Iatrogenic Injury: Perforation During Colonoscopy

Post-colonoscopic perforation is rare. These iatrogenic perforations occur in approximately 1 in 1,000 patients. The clinical presentation varies from acute abdomen to subtle clinical findings.

In diagnostic colonoscopy the rectosigmoid is the most common site of perforation followed by the cecum, while post-polypectomy perforation, in therapeutic colonoscopy, occurs at the site of the excised polyp. A perforated site is typically a large anti-mesenteric tear of colonic wall if it is caused by the shaft of the endoscope. Furthermore, a smaller perforation can be found in an injury from the tip of the endoscope. If a perforation is clinically suspected and conventional chest and abdominal X-ray exclude free abdominal or subdiaphragmatic air, air within the colonic wall, subcutaneous emphysema, or pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax, a CT is recommended [7, 18]. As we said before, about direct findings, in iatrogenic perforation, we can find free retroperitoneal gas in the anterior pararenal space caused by perforation of the posterior walls of the sigmoid, ascending, and descending colon.

When we have anterior wall sigmoid perforation, the direct sign is discontinuity of the bowel wall with free extraluminal air near the lesion and eventually in the intraperitoneal spaces (Figs. 9.5 and 9.6).

Fig. 9.5

Gaseous distention of the colon due to recent colonoscopy (arrows)

Fig. 9.6

Discontinuity of the anterior sigma wall (arrow) with modest quote of perivisceral free air (curved arrow)

9.10 Perforation After Colon: Rectal Surgery (Anastomotic Dehiscence)

The most alarming complication following colorectal surgery is anastomotic leakage which is associated with a high mortality rate.

Different factors are involved: the type of surgery (higher risk after restorative proctocolectomy or rectal resection), the extraperitoneal site of the anastomosis, the type of the anastomosis (higher risk after coloanal or ileal-anal pouch or colorectal), the stapled anastomosis, and the intraoperative complications.

CT represents the modality of choice for the optimal recognition of postoperative complications and for the assessment of patients with postoperative sepsis. Most postoperative CT features overlap between patients with and without clinically important anastomotic leak (CIAL). The only feature seen statistically more frequently with CIAL is peri-anastomotic loculated fluid containing air.

Evident anastomotic leak is suspected on the basis of a large hydropneumoperitoneum or if pneumoperitoneum enlarges on successive examinations. Usually the collection is situated between the rectum and the sacrum, and the rectum is anteriorly displaced by the collection. Sometimes we can find the fluid collections around the anastomotic site also in patients without anastomotic leakage. The key point for suspicion of a leakage is visualization of air or contrast into the fluid collection (Figs. 9.7 and 9.8) [22, 23].

Fig. 9.7

Sigma resection with air-fluid collections around the colon – rectal anastomosis (arrows)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree