George M. Bridgeforth and Mark Nolden

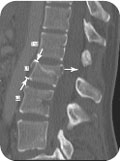

A 23-year-old woman, who drank a six-pack of beer before swinging over a brook on a rope, slipped and fell into the water below, landing on her feet without losing consciousness. she complains of back pain.

CLINICAL POINTS

- Patients with narrow cervical spinal canals may have a central spinal stenosis.

- A head CT may be indicated after high-impact spinal injuries.

- A spinal CT may be indicated if there is evidence of the following:

- Extreme pain

- Focal tenderness

- Focal neurological signs of spinal trauma (acute weakness, numbness, loss of reflexes, loss of bowel tone)

- Evidence of spinal ecchymosis, hematomas, or crepitus

- Extreme pain

- Not all patients with acute spinal cord injuries exhibit neurologic impairment.

Clinical Presentation

All patients with high-impact spinal cord injuries from trauma, motor vehicle accidents, sports, and recreational or competitive diving have unstable spinal injuries until proven otherwise. In addition, there is a strong correlation of traumatic brain injuries associated with these cases. All patients with an acute spinal cord injury who are mentally obtunded or have an impaired mental status from drug or alcohol intoxication have a traumatic brain injury until proven otherwise. For most trauma cases, a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan is sufficient to rule out an acute subdural hematoma. Box 3.1 lists the indications for a head CT.

Various clinical clues may help differentiate between an acute spinal cord injury and a traumatic brain injury. Although it is uncommon, patients with an acute spinal cord injury may present without neurological impairment. Primary care physicians need to know how to distinguish between stable and unstable injuries.

In most cases of acute spinal cord injury, a neighboring fracture or dislocation is usually evident.

Acute spinal cord injuries usually present with bilateral neurological impairments. Although diffuse brain damage following closed head injuries may present with bilateral upper motor signs, the impairment caused by a spinal cord injury is usually below a specific neurological level. Upper motor neuron signs are characterized by motor weakness, spasticity, hyperreflexia, and upgoing plantar (Babinski) responses, and they are usually associated with a sensory impairment. In contrast, head injuries are usually associated with an impaired mental status, bilateral upper motor neuron signs with diffuse damage, or unilateral upper motor neuron signs on the opposite side with focal damage. In addition, acute cranial nerve impairments affecting the speech, vision, or hearing are common.

Patients with acute spinal cord injuries above the midthoracic level exhibit acute spinal shock. Acutely, spinal shock is characterized by hypotension (blood pressures less than 100/70 mm Hg), motor weakness, poor or absent reflexes, loss of voluntary bowel tone (the patient does not exhibit a forceful strain during a rectal examination), and sensory impairment. These findings are below the level of the spinal cord injury. Several days later, when the patient recovers from spinal shock, they then exhibit upper motor neuron signs below the level of the spinal cord injury. Patients with spinal cord injuries below the midthoracic region develop acute paraplegia of the lower extremities. The bowel and bladder problems affecting paraplegics are different than those affecting tetraplegics (quadriplegics).

Box 3.1 Indications for Computed Tomography of the Head

Severe headache with focal neurological signs or acutely impaired cranial nerve signs (sudden onset of visual, speech, or hearing disturbances)

Head injury with recurrent nausea and vomiting

Obtunded mental status including drug or alcohol intoxication or short-term cognitive-memory impairments

Poor result on Glasgow Coma Scale

Skull fracture

Major traumatic injuries above the clavicle

Age more than 60 years

Coagulation disorder (or taking anticoagulants)

Acute onset of seizure

Traditionally, the Frankel classification, a functional classification, was used to group acute spinal cord injuries into four major classes (Box 3.2). The American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) classification, which is presented in greater detail in Chapter 4, has replaced the Frankel classification. The ASIA classification system adds a Class E, in which both motor and sensory functions are normal.

It is important to remember that it is possible to have serious fracture or dislocation of the spine despite normal neurological function. An individual with an unstable spinal cord injury to the vertebral column may have normal or near-normal neurological function. Therefore, all patients who are subject to acute spinal cord trauma have unstable injuries to the spine until proven otherwise by a history, a thorough neurological assessment, initial radiographs, and a CT scan.

If a spinal fracture is suspected, the patient should be immobilized on a spine board. Moreover, if there is accompanying head, cervical, or upper chest wall trauma, the neck should be placed in a hard cervical collar as well. The patient should be referred immediately to a high-level emergency trauma center, and a CT scan should be obtained.

Box 3.2 Functional Classification of Acute Spinal Cord Injuries

Class A: complete motor and sensory loss below the level of the spinal cord injury

Class B: preserved sensory function but not motor function below the level of the spinal cord injury

Class C: preservation of motor function below the level of the spinal cord injury, although it is nonfunctional

Class D: preservation of functional motor strength below the level of the spinal cord injury

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree