George M. Bridgeforth and Mark Nolden

A 66-year-old man presents with chronic back pain and pain in both thighs.

CLINICAL POINTS

- The presence of constitutional symptoms warrants evaluation.

- Metastatic disease should be suspected in any patient with severe low back pain, especially if he or she is older than 50 years of age.

- Middle-aged patients (especially males) who experience the sudden onset of lower extremity motor weakness without low back pain may be experiencing the initial onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Clinical Presentation

The etiology of low back pain is probably multifactorial. Most people do not engage in regular exercise to strengthen their core abdominal muscles. As a result, excessive loads from obesity, improper lifting techniques, and fatigued muscles from poor core stability place increased strain on the disc and the surrounding neurological structures. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in normal individuals without back pain have shown some evidence of degenerative disc disease in about one-third of patients. Therefore, evidence of mild disc protrusions without gross herniations (i.e., pressing on the nerves or the spinal cord) is not sufficient evidence for long-term disability. Routine radiographs for nonradiating low back pain usually are not required during the initial evaluation but should be considered if the patient does not improve by the end of 4 to 6 weeks. The mechanism of injury in degenerative disc disease is a non–trauma-related degenerative condition.

Metastatic disease should be suspected in any patient presenting with severe low back pain who is older than 50 years of age (but certainly it has been reported in younger individuals as well—age is not an excluding factor). Constitutional symptoms such as generalized weakness and weight loss, a positive personal history of a preexisting cancer, a family history of cancer, a strong smoking history with pulmonary abnormalities, an undiagnosed breast mass, or new-onset hematuria are indications for an initial radiographic evaluation and further workup (MRI or computed tomography [CT] scan). In addition, the acute onset of radicular findings (numbness, weakness of the lower extremities with a positive straight leg raising [pain that radiates down the leg past the knee with straight leg elevation]) also indicates that additional workup is necessary.

During the history, the examiner should inquire about the severity of the pain, its precipitating and palliative factors, and onset, duration and timing. It is important to inquire whether the pain is radiating or nonradiating. Radicular pain from disc herniations is usually unilateral. Pain that radiates to the groin may be secondary to an L3 radiculopathy or degenerative hip disease. L4 radiculopathies radiate to the skin or the ankle. L5 radiculopathies radiate to the great toe, and S1 radiculopathies radiate to the outside of the foot. In addition, it is important to inquire about motor weakness, especially a foot drop. Ninety percent of radiculopathies affect the L5 or S1 nerve roots (Hoppenfeld, 1976).

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

- Low back pain or stiffness

- Limited range of motion

- Possible neurological impairment

- Radicular findings with a disc herniation (positive straight leg raising, motor weakness, sensory loss, diminished absent reflexes)

- Cauda equina injury (rare)

Patients with increasingly severe low back pain, radicular pathology, acute foot drop, or incontinence should be evaluated promptly by a specialist. The new onset or a foot drop or a cauda equina syndrome (motor weakness of the lower extremities, sensory impairment of the lower extremities, and bowel or bladder incontinence) constitutes a medical emergency and warrants an immediate referral. Cauda equina injuries are rare.

Radiographic Evaluation

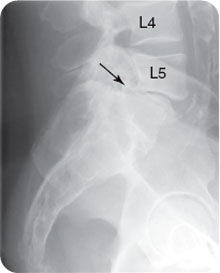

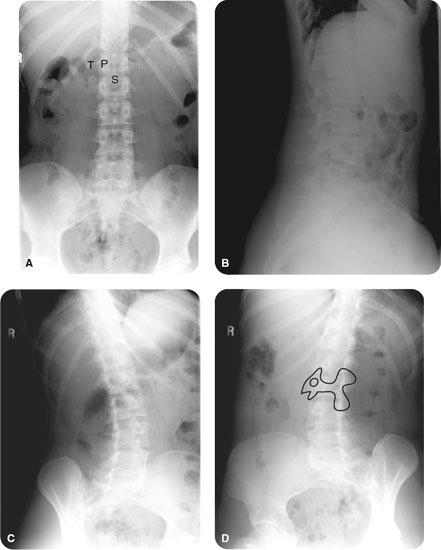

It may not be necessary to order radiographs on initial assessment of nontraumatic cases of low back pain. However, radiographs are recommended for any serious injuries secondary to acute trauma. In addition, radiographs may be considered in patients with severe low back pain who are older than 50 years of age, in patients with metastatic cancer, or in patients whose status deteriorates secondary to low back pain. Tests to order include standard radiographs of the spine—anteroposterior (Fig. 1.1A), lateral (Fig. 1.1B), and oblique views (two; Fig. 1.1C, D). MRI (or CT) may be used in patients with suspected metastatic disease, new-onset radicular symptoms (numbness, weakness, foot drop, diminished or absent reflexes), or focal neurological symptoms.

FIGURE 1.1 A 19-year-old woman without a history of injury presents with back pain of 6-month duration. Normal (A) anteroposterior, (B) lateral, and (C and D) bilateral oblique views demonstrate no acute or chronic findings. “Scottie dog” is evident on the oblique projections where the neuroforamina are easily seen. (T = transverse process, P = pedicle and S = spinous process).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree