George M. Bridgeforth, Kevin Bozic, and Jay Patel

A 79-year-old obese woman presents with left hip pain after a fall. she has difficulty walking.

CLINICAL POINTS

- Patients often complain of chronic hip pain.

- A history of morning stiffness is frequent.

- Both hips are usually affected.

Clinical Presentation

Degenerative disease of the hip, a large weight-bearing joint, may affect elderly patients or patients who have been taking steroids for long periods. Complaints of long-term hip or groin pain are not uncommon. Reports of morning stiffness are very common, usually with osteoarthritis. The mechanism of injury is a degenerative process. Usually degenerative joint disease is bilateral; however, one hip may be affected more severely than the other. It is helpful if other signs of osteoarthritis are present. Common findings include hypertrophy of the knees and the presence of Heberden nodes (joint hypertrophy) of the distal interphalangeal joints affecting some of the fingers. Patients with degenerative hip disease have impaired range of motion of the affected hip. Patients exhibit limited flexion as well as internal and external rotation. Moreover, they have an antalgic gait. In mild cases, the limp may be slight. In severe cases, the pain can be severe, and complaints of falling are common. Hip fractures from falls frequently occur in elderly patients, and these are associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Two helpful clinical tests are the Stinchfield test and the Faber test. A Stinchfield test is performed with the patient in supine position. The patient is asked to elevate his or her leg (with the knee straight) to 20 or 30 degrees. A positive test (which indicates intracapsular pathology) is characterized by hip pain or groin pain. If the patient does not complain of pain, the examiner may apply a steady downward force at the ankle in the direction of the examining table. In that case, pain that is reproduced at the ipsilateral hip or groin represents a positive test. The Stinchfield test is different than the Lasègue test, a straight leg-raising test used for back pain. With a positive Lasègue test, the patient complains of radicular low back pain that radiates from the back down the leg, generally at an elevation of 30 to 60 degrees. The Stinchfield test is also different from the Lhermitte test. In a positive Lhermitte test, low back pain radiates down the opposite (i.e., nonelevated) leg. It indicates radicular pathology on that side.

When screening for osteoarthritis, some examiners may prefer to use a Faber (Patrick test). Faber stands for (hip) flexion, abduction, and external rotation. In this maneuver, the leg is placed into a frog leg position. In other words, the hip is placed into abduction by placing the foot across the opposite knee. After stabilizing the opposite pelvis with one hand, the examiner applies pressure against the bent knee in a downward direction toward the examining table. Pain in the groin or the hip indicates hip pathology. However, pain along the sacroiliac joint indicates sacroiliac pathology. Patients with intra-articular pathology from an avascular necrosis may present with similar clinical findings; further radiologic evaluation is warranted.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

- Positive Stinchfield test (pain with active straight leg raise)

- Pain-limited passive range of motion

- Antalgic gait (limp)

Patients with hip fractures exhibit moderate to marked pain and tenderness to palpation. Clinical findings such as acute swelling and ecchymosis (i.e., bruising) may represent a recent fracture. There is impaired range of motion with an antalgic gait as well. Patients with contusions presents with similar findings but there is no evidence of a fracture.

Patients with metastatic disease may present with similar findings of severe hip pain, with impaired range of motion. Unexplained weight loss, a history of cancer, or a family history of cancer may be an important clue. The majority of metastatic diseases are caused by breast, lung, and prostate cancers. They metastasize to the hip, spine, and pelvis. Metastatic diseases may not be apparent on the initial radiographs. However, if the patient has other clinical findings such as a palpable breast mass, lung mass, hematuria (kidney cancer), or a prostrate nodule, then computed tomography (CT) with 2-mm sections might be warranted. Some clinicians prefer bone scans, but a positive bone scan is usually followed by a CT scan anyway. If there is an associated degenerative arthritis, a bone scan may not distinguish between the two conditions.

A trochanteric bursitis is characterized by focal pain and soreness over the greater trochanter. Essentially, it is a diagnosis of exclusion (radiographs do not reveal any fractures). It is treated with cold pain and analgesic medication. Severe cases may require a steroid injection into the trochanteric bursa. Rheumatoid arthritis may be identified by rheumatoid changes affecting other joints such as knees, wrists, metacarpals, pip joints, and ulnar deviation of hands.

Osteomyelitis of the hip is rare. The examiner should look for a portal of infection (e.g., open hip fractures, intravenous drug abuse). The patients manifest marked constitutional signs: elevated fevers, chills, and diaphoresis (sweating) with severe pain.

It is important to examine elderly patients for other signs of bruising or fractures, because elder abuse should be suspected if multiple areas of unexplained bruising are encountered. The elderly are more prone to develop osteoporosis; therefore, even minor falls may cause a serious hip fracture. For this reason, polypharmacy should always be monitored, especially in the elderly.

NOT TO BE MISSED

- Hip contusion/fracture

- Dislocation

- Trochanteric bursitis

- Avascular necrosis

- Metastatic disease

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Osteomyelitis

- Bone tumors

Radiographic Evaluation

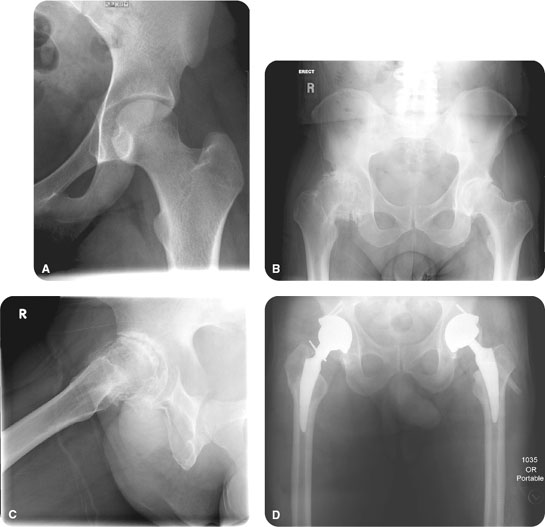

Plain radiographs of the hip(s) (anteroposterior [AP] and lateral [frog leg]) views should be ordered. There are four radiological hallmark findings for degenerative joint disease (osteoarthritis), which are listed as follows:

- Narrowing of the joint space

- Subchondral sclerosis

- Osteophyte (bone spur) formation

- Subchondral cyst formation (see Fig. 10.1)

All four findings need not be present. For example, in early degenerative joint disease, there may be narrowing of the joint space associated with early subchondral sclerosis and osteophyte formation. The subchondral sclerosis is a reactive process to the articular thinning. Essentially, the bone is trying to repair itself. Moreover, subchondral cysts may be difficult to identify. The joint space narrowing and the early osteophyte formation manifest themselves as mild joint hypertrophy. These findings are best appreciated on the AP view.

FIGURE 10.1 (A) A 19-year-old woman with sickle cell disease presents with hip pain, which magnetic resonance imaging proves negative for avascular necrosis. Note the smooth contour of the femoral head and acetabulum in the normal left hip. The joint space is preserved, and there are no bony osteophytes. Compare with a 53-year-old man with severe bilateral hip pain (B), which is an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis demonstrating bilateral osteoarthritis, which is more severe on the right. (C) A frog-leg view of the right hip joint demonstrates near-total narrowing of the joint space, subchondral sclerosis, osteophytes, and subchondral lucencies, probably representing subchondral cysts. (D) An anteroposterior radiograph of the bilateral hip joints nearly two years after the initial examination demonstrates bilateral total hip prostheses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree