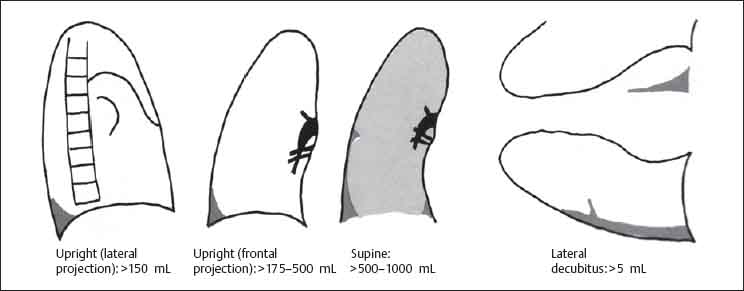

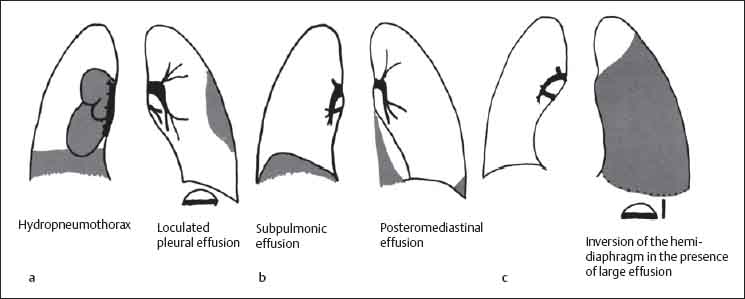

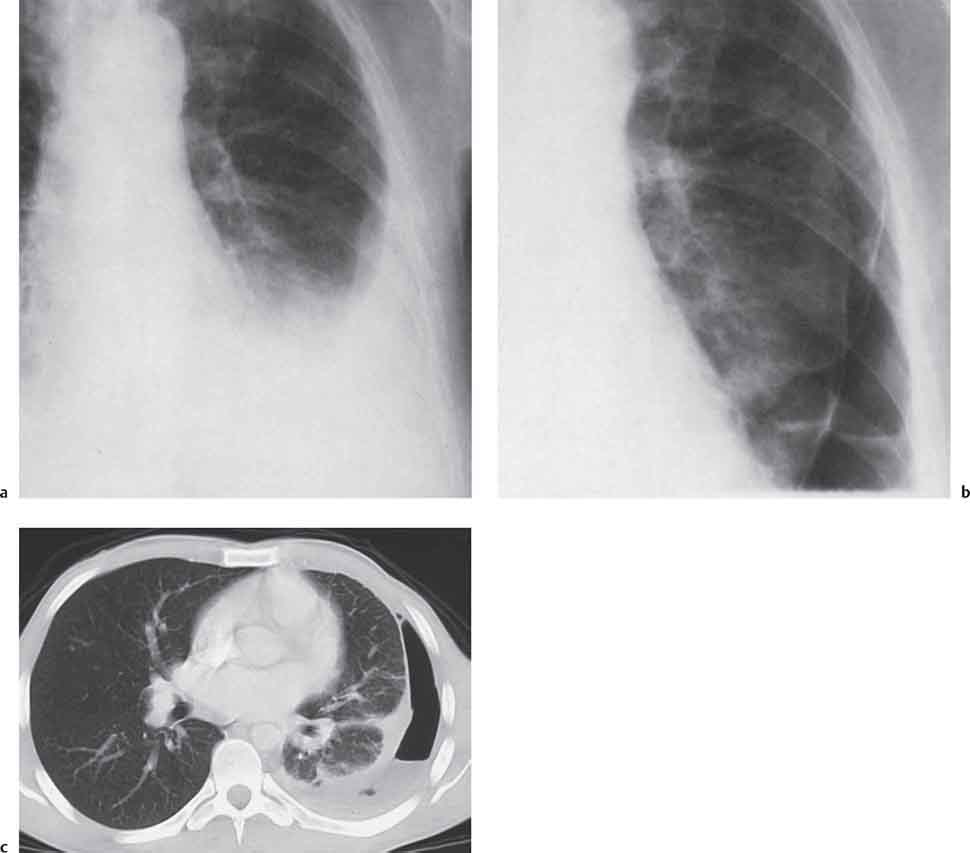

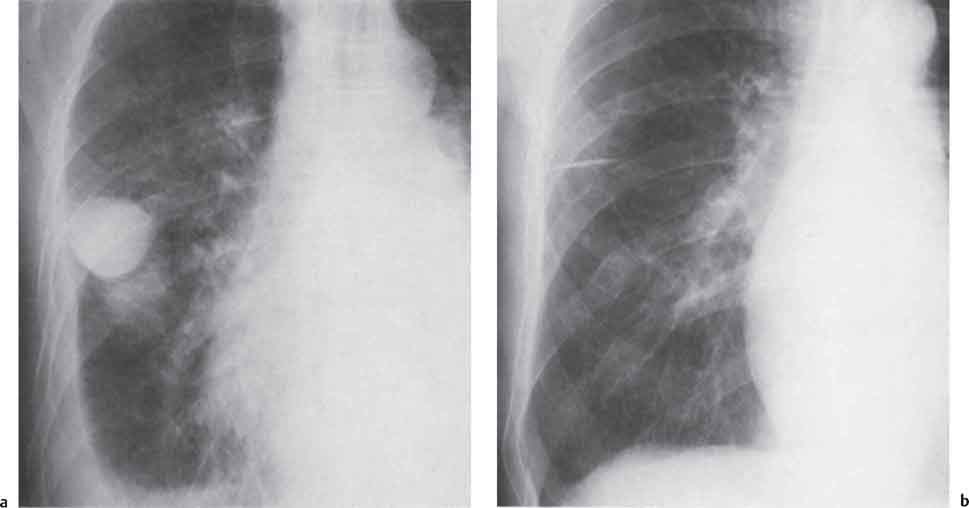

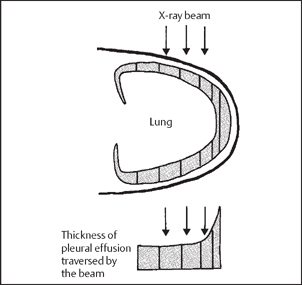

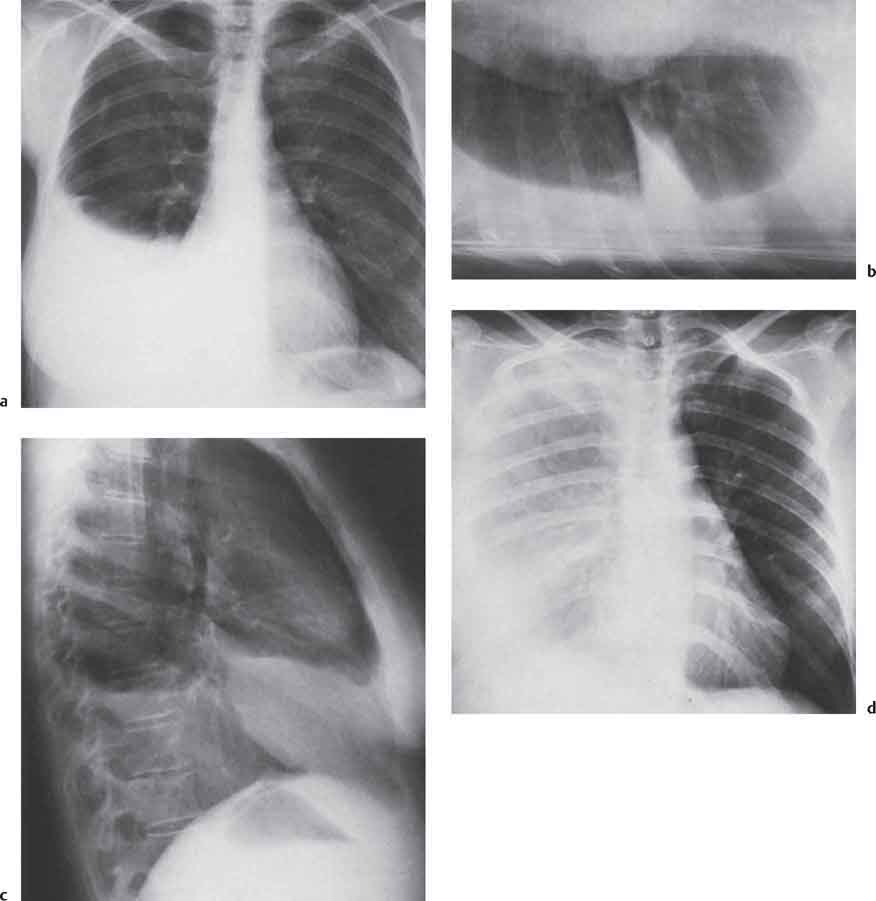

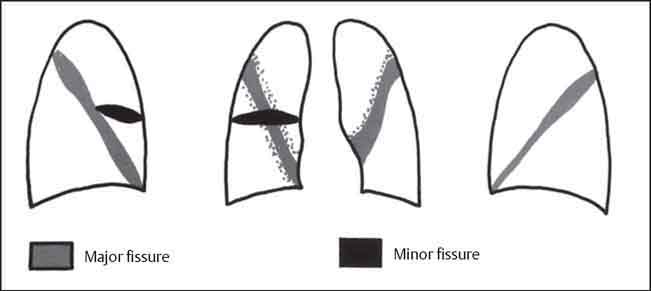

9 Diseases of the Pleura, Diaphragm, and Chest Wall A pleural effusion is a pathologic fluid collection within the pleural cavity. Normally 10–15 mL of fluid is present and this serves as a lubricant between the parietal and visceral pleural layers. Pleural effusions may reach volumes of up to a few liters and these large effusions result in compression of the underlying lung, contralateral displacement of the mediastinum, and depression of the hemidiaphragm. Table 9.1 Etiology of pleural effusions in the U.S. (from R. W. Light: Pleural Diseases, 1983) Table 9.2 Causes of pleural effusion M = diseases in which the chest radiograph generally shows other changes besides pleural effusion. O = diseases in which pleural effusion may be the only radiographic finding (from Light). Pleural effusions may be classified according to their composition: Effusions are frequently asymptomatic but may cause pleuritic chest pain and splinting of the hemidiaphragm with decreased respiratory excursion. Large effusions may result in dyspnea. On auscultation, breathing sounds are diminished. Table 9.3 Causes of chylothorax (modified from Reeder and Felson 2003) Fig. 9.1 Pleural effusion on PA chest radiograph. The effusion surrounds the entire lung base but it is visible as a meniscus only when it is tangential to the x-ray beam (from Greene, McLoud, and Stark 1977). The shape of the effusion results from: Pleural fluid is mobile and therefore its distribution is position-dependent. This accounts for its varying radiographic appearances (Figs. 9.1–9.3). Upright position: Fig. 9.2 Limits of detectability of pleural effusion (from Moskowitz 1973). Fig. 9.3a-d Chylothorax. Fluid layering dependently in the lateral decubitus view appears as a crescent-shaped opacity entering the minor fissure (b). On the supine view, the fluid causes general haziness of the hemithorax (d). The etiology of the chylothorax was a Milroy-Trenaunay malformation of the lymphatic vessels. Fig. 9.4a-c Variants of pleural effusion. Supine position: Effusions are only visible on supine radiographs when they exceed 500 mL Manifestations include: In contrast to pneumonia or atelectasis, the pulmonary vessels are well defined with small to moderate effusions and there is no evidence of an air bronchogram. Lateral decubitus position: Fluid collects between the lateral chest wall and the lung, producing a band of opacification which may enter the minor fissure. Postmortem studies have shown that as little as 5 mL of fluid may be detected on the lateral decubitus view (Moskowitz et al. 1973). If the depth of the effusion (“band” thickness) is less than 1 cm, then the effusion is small. Atypical forms of pleural effusion (Figs. 9.4, 9.5): Fig. 9.5a-c Malignant pleural effusion in breast carcinoma (a). Hydropneumothorax developed following thoracentesis (b). CT shows visceral pleural thickening and fluid extending into the major fissure (c). Fig. 9.6 Interlobar effusions. Fig. 9.7a,b Fissural effusion appears as a round opacity in the minor fissure in a patient with congestive heart failure. Radiograph post treatment shows minimal residual fissural thickening.

Diseases of the Pleura

Pleural Effusion

Heart failure

500 000

Bacterial pneumonia

300 000

Malignant tumors

200 000

• Lung

60 000

• Breast

50 000

• Lymphoma

40 000

• Miscellaneous

50 000

Thromboembolism

150 000

Viral pneumonia

100 000

Hepatic cirrhosis with ascites

50 000

Gastrointestinal disease (e. g., pancreatitis)

25 000

Collagen diseases

6 000

Tuberculosis

2 600

Asbestosis

2 000

Mesothelioma

450

Vascular

O

Pulmonary infarction

M

Heart failure

O

Constrictive pericarditis

Inflammatory

O

Tuberculosis

M

Parapneumonic effusion (viral, mycoplasma, bacterial, fungal)

O

Collagen diseases (SLE, rheumatoid arthritis)

O

Postinfarction Dressler“s syndrome

O

Whipple disease

O

Mediterranean fever

O

Recurrent familial polyserositis

Neoplastic

M

Bronchial carcinoma

O

Lymphoma

O

Metastatic pleural adenocarcinoma

O

Mesothelioma

Iatrogenic

O

Intrapleural infusion (e. g., due to faulty catheter placement)

M

Postthoracotomy

M

Radiotherapy

Traumatic

O

Hemothorax

O

Esophageal rupture

O

Chylothorax

Mediastinal

M

Superior vena caval obstruction

M

Aortic rupture

O

Esophageal fistula (e. g., carcinoma)

O

Thoracic duct fistula (filariasis, carcinoma)

M

Ruptured dermoid cyst

Subphrenic Abdominal

O

Pancreatitis

O

Subphrenic abscess

O

Cirrhosis with ascites

O

Meigs’ syndrome (ascites associated with ovarian tumor)

Miscellaneous

O

Asbestosis

O

Nephrotic syndrome

O

Myxedema

O

Uremia

O

Spontaneous pleural hemorrhage due to coagulopathy

O

Congenital lymphedema (Milroy)

Pathology

Clinical Features

Traumatic

Tumor invasion (bronchial carcinoma, mesothelioma, Hodgkin“s disease, etc.)

Filariasis

Left subclavian vein thrombosis

Lymphangioma, lymphangiomatosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis

Iatrogenic (postthoracic surgery)

Idiopathic

Radiologic Findings

Chest Radiograph

Conventional tomography allows more accurate differentiation based on the homogeneity of the effusion versus the heterogeneity of atelectatic lung. However, today CT is usually performed when there is diagnostic difficulty.

Ultrasound

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree