Case presentation

An 83-day-old female, with a history of congenital hydrocephalus and chronic subdural fluid collections, presents with a 1-week history of increasing fussiness and decreasing oral intake. She has a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt that was placed soon after birth; there has been no revision of the shunt since placement. The mother reports to you that there has been no fever, vomiting, diarrhea, or rash, and there has been good urine output. She tells you that the child was seen by her primary care provider several days ago and was noted to have an increased head circumference compared to previous measurements, but she cannot elaborate further except to say she was told to make a follow-up appointment with the child’s pediatric neurosurgeon.

The child’s physical exam reveals an irritable, yet nontoxic, child. She is afebrile. Her respiratory rate is 40 breaths per minute with a heat rate of 180 beats per minute. A blood pressure is not documented. She has a small anterior fontanelle that seems full although the mother is unable to tell you how the fontanelle usually feels. She has palpable shunt tubing on the right parietal portion of her scalp; you are unable to feel a reservoir. The rest of her examination is unremarkable.

Imaging considerations

Plain radiography

A series of plain radiographs, more commonly known as a shunt series, is often the first step in the evaluation of a possible shunt malfunction. The purpose of these images is to examine the shunt tubing for cracks, kinking, or disconnections. A full series will evaluate the entire length of the shunt. The tubing is often coiled in the peritoneal cavity; this is to allow a patient to “grow” into their shunt and reduce the number of revisions necessary to compensate for a child’s growth. Recently, however, the utility of obtaining a traditional shunt series has come into question. , Some experts have proposed proceeding directly to neuroimaging in children when shunt malfunction is suspected, given the low sensitivity of plain radiography in detecting shunt malfunction. ,

The programmable valve settings on a shunt may be seen with a “valve view.” This view can be used to confirm shunt settings.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound has been used to evaluate optic nerve sheath diameter as a measurement of intracranial pressure and has begun to be explored as a possible imaging test to evaluate a patient for shunt malfunction. In some studies, when combined with plain radiography shunt series imaging, ultrasound has been shown to be helpful in detecting shunt malfunction in patients with low pretest probability of shunt malfunction. However, another study using ocular ultrasound as a single imaging modality to screen for shunt malfunction demonstrated low sensitivity and specificity. Further research is needed to understand the potential role of ultrasound in patients with suspected shunt malfunction.

Neuroimaging

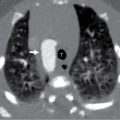

Computed tomography (CT)

Usually readily available, and performed without intravenous (IV) contrast for this indication, CT offers rapid assessment of the size of a child’s ventricles, assisting the clinician in ascertaining if a shunt malfunction exists. Sedation is rarely, if ever, required. CT exposes the patient to ionizing radiation. These children often have had multiple studies, and the potential of sequelae from exposure to ionizing radiation is cumulative. Minimizing the duration and amount of radiation exposure by practicing ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) principles helps mitigate this risk. Limited-use CT protocols have been proposed; one center initiated a pilot study using a four-slice protocol (third ventricle, fourth ventricle, lateral ventricle, and basal ganglia levels) to evaluate ventricular size. Another institution created a clinical pathway that used a full coverage (i.e., complete brain visualization) but reduced-dose cranial CT and eliminated routine radiographic shunt series, with directed plain films obtained only for specific indications. Results showed this clinical pathway to reduce CT effective radiation dose by approximately 50% and to decrease effective dose from radiographs by 64%, with no adverse effect on patient care. CT may be the only option available (even in tertiary care pediatric facilities), and the risk of complications by either not identifying shunt malfunction or delaying treatment can be significant.

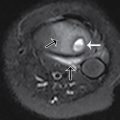

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI has seen increasing use in VP shunt evaluation. There is no exposure to ionizing radiation and IV contrast is not required. Fast acquisition MRI has become an alternative to conventional brain MRI, allowing good visualization of ventricular size with a short scanning time. Diagnostic accuracy is comparable to CT, and sedation needs have diminished with rapid acquisition protocols. ,

Several issues complicate the use of MRI. MRI is often not readily available on demand, even in pediatric facilities. The time required to complete an adequate study sometimes necessitates the use of sedation, particularly in patients who may be agitated, although fast acquisition MRI has made this need less common.

Most programmable VP shunt valves are MRI-compatible. However, some programmable shunt valves are programmed using magnets, and an MRI evaluation can reset the current shunt settings. It is important to ascertain if the child has a programmable shunt and if the shunt valve setting requires evaluation after scanning. One can still obtain the study, but a post-MRI “valve view” (a one-view plain radiograph) to confirm that the settings have not changed should be performed. ,

Regardless of the neuroimaging method used, there are two important aspects to consider. First, expertise in the interpretation of pediatric neuroimaging is important in determining if shunt malfunction exists. Second, prior neuroimaging studies are critical. A comparison should be made between the current neuroimaging study results and past study results. Ideally, similar modalities should be compared, but comparison of current CT to prior MRI and vice versa are acceptable.

Imaging findings

This child had a radiographic shunt series ( Figs. 27.1–27.4 ) and a fast acquisition MRI ( Figs. 27.5–27.7 ). Selected views are included.