10 Duplex assessment of upper-limb arterial disease

INTRODUCTION

In contrast to lower-limb arteries, atherosclerotic disease in the upper extremities is rare and accounts for approximately 5% of all extremity disease (Abou-Zamzam et al. 2000). The most commonly affected sites are the subclavian (SA) and axillary arteries. The disorder is sometimes associated with extracranial carotid artery disease. Radiotherapy in this region, resulting in fibrosis and scarring, can also cause damage to the SA and axillary arteries. Compression of the SA in the area of the thoracic outlet, known as thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS), can produce significant upper-limb symptoms.

ANATOMY OF THE UPPER-EXTREMITY ARTERIES

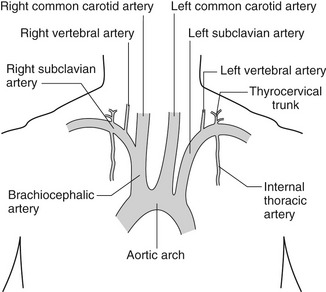

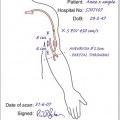

The anatomy of the upper-extremity arteries is illustrated in Figures 10.1 and 10.2. The left SA divides directly from the aortic arch, but the right SA originates from the innominate or brachiocephalic artery. The thoracic outlet is the point where the SA, subclavian vein, and brachial nerve plexus exit the chest. The SA runs between the anterior and middle scalene muscles and passes between the clavicle and first rib to become the axillary artery. The diameter of the SA ranges from 0.6 to 1.1 cm. The SA has a number of important branches, including the vertebral artery and internal thoracic artery (also referred to as the mammary artery), which is frequently used for coronary artery bypass surgery.

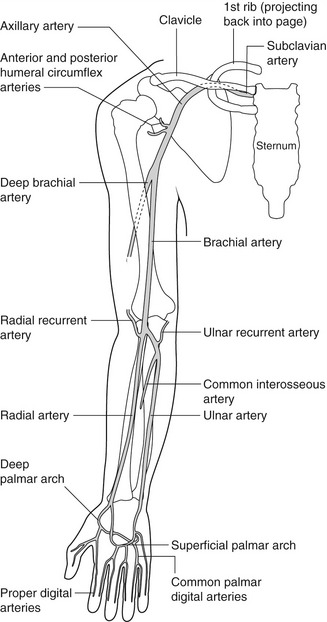

The axillary artery becomes the brachial artery as it crosses the lower margin of the tendon of the teres major muscle, at the top of the arm. The diameter of the axillary artery ranges between 0.6 and 0.8 cm. The brachial artery then runs distally on the medial or inner side of the arm in a groove between the triceps and biceps muscles. The deep brachial artery divides from the main trunk of the brachial artery in the upper arm and acts as an important collateral pathway around the elbow if the brachial artery is occluded distally. The brachial artery runs in a medial to lateral course over the inner aspect of the elbow (cubital fossa) and then divides, 1–2 cm below the elbow, into the radial and ulnar arteries. However, the bifurcation can be quite variable in position and can sometimes be seen in the upper arm. The ulnar artery dives deep beneath the flexor tendons in the upper forearm. The radial artery runs along the lateral side of the forearm toward the thumb and is palpable at the wrist. The ulnar artery runs along the medial side of the forearm and is sometimes the dominant vessel of the forearm. The common interosseous artery is an important branch of the ulnar artery in the upper forearm as it can act as a collateral pathway if the radial and ulnar arteries are occluded. The radial artery supplies the deep palmar arch in the hand, and the ulnar artery supplies the superficial palmar arch. There are usually communicating arteries between the two systems. In some people only one of the wrist arteries will supply the palmar arch system. The fingers are supplied by the palmar digital arteries. There are a number of anatomical variations in the arm that are shown in Table 10.1. The arms normally develop good collateral circulation around diseased segments. The major collateral pathways of the arm are summarized in Table 10.2.

Table 10.1 Anatomical variations of the upper-limb arteries

| ARTERY | VARIATION |

|---|---|

| Left subclavian artery | Common origin with common carotid artery from aortic arch |

| Brachial artery | High bifurcation of brachial artery |

| Radial artery | High origin from axillary artery |

| Ulnar artery | High origin from axillary artery |

Table 10.2 Major collateral pathways of the upper arm

| DISEASED SEGMENT | NORMAL DISTAL ARTERY | POSSIBLE PATHWAYS |

|---|---|---|

| Proximal subclavian artery | Distal subclavian artery | Vertebral artery, internal thoracic artery, and thyrocervical trunk |

| Distal subclavian or proximal axillary artery | Distal axillary artery | Collateral flow to the circumflex humeral arteries |

| Brachial artery | Distal brachial artery or proximal radial and ulnar arteries | Deep brachial artery to the recurrent radial and ulnar arteries |

| Radial and ulnar arteries | Distal radial and ulnar arteries | Interosseous artery and branches of the recurrent radial and ulnar arteries |

SYMPTOMS AND TREATMENT OF UPPER-LIMB ARTERIAL DISEASE

The main causes of upper-limb disorders are shown in Box 10.1. Many patients with chronic upper-limb arterial disease experience few symptoms because of the development of good collateral circulation in the arm. However, some patients complain of aching and heaviness in the arm following a period of use or exercise. Patients with significant chronic symptoms can be treated by angioplasty, provided that the lesion is suitable for dilation. Arterial bypass surgery is rarely performed in the upper extremities. Acute obstructions can produce marked distal ischemia, and the forearm and hand may be cold and painful. In many cases of acute ischemia the condition of the arm and hand improves with appropriate anticoagulation. However, embolectomy, thrombolysis, or bypass surgery may be performed if there is persistent distal ischemia. Trauma, due to injury or stab wounds to the arm or shoulder, can result in arterial damage, requiring local repair or bypass surgery. SA or axillary artery aneurysms can be bypassed with grafts, although in some cases endovascular repair can be performed by deploying a covered stent across the aneurysm to exclude flow in the aneurysm sac. Occasionally, patients with arteriovenous malformations will be encountered. These malformations range in size and distribution and can affect the fingers, hands, or arm.

BOX 10.1 Common causes of symptoms involving the arterial and microvascular circulation of the arms and hands

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR DUPLEX ASSESSMENT OF UPPER-EXTREMITY ARTERIAL DISEASE

A minimum of half an hour should be allocated for an upper-limb examination.