Case presentation

A 4-year-old male presents with right elbow pain and swelling. He was playing on his school’s monkey bars when he fell, landing on his right arm and elbow. He fell approximately 3 feet. There was no reported loss of consciousness and the child immediately cried. He complained of elbow pain and was brought directly for evaluation.

The child is afebrile and has age-appropriate vital signs. He has no signs of trauma to his head. He has no neck or back pain, crepitus, swelling, or deformity and is ambulatory. He does not appear to have any injury to his shoulders or his left arm. He initially refuses to move his right arm at the elbow, which is swollen. With some coaxing, he has movement at the elbow but this is limited secondary to pain. There is not any upper arm, forearm, wrist, hand, or digit pain, swelling, or deformity. He is grossly neurovascularly intact.

Imaging considerations

Plain radiography

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the elbow are usually performed to evaluate for fracture. In general, these views will suffice but an internal oblique view is useful to assess the degree of displacement for condyle fractures. One study reported significant discrepancies between the apparent displacement of lateral condyle fracture fragments on AP and lateral views, compared to an internal oblique view. This study showed that a majority of fractures that were detected on AP and lateral views had a different degree of displacement and fracture pattern on an internal oblique view, and the authors recommended adding an internal oblique view to the AP and lateral views to assess lateral condyle fractures. , Internal oblique radiography has also been recommended by some authors at follow-up after initial two-view radiography, as useful for detecting displacement in initially nondisplaced or minimally displaced lateral condyle fractures.

As with lateral condyle fractures, two-view imaging of medial condyle fractures is usually utilized. Some have suggested utilization of internal oblique views in these fractures, although in another case series, the authors identified all fractures with AP and lateral views.

Medial epicondyle fractures are visualized with AP and lateral views. Oblique views, however, can help determine fracture fragment displacement and should be obtained.

Computed tomography (CT)

CT is not indicated as a first-line test in the evaluation of most elbow injuries. In cases where an injury is particularly complex, noncontrast CT can provide additional information about the anatomy of the injury. Pediatric Orthopedic consultation should be considered prior to obtaining CT.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI is also not a first-line imaging test for acute elbow injury. It has proven useful for follow-up imaging in cases where the detection of displacement by plain radiography is difficult. MRI has also been utilized in nondisplaced fractures to better delineate whether a fracture is complete or not.

Imaging findings

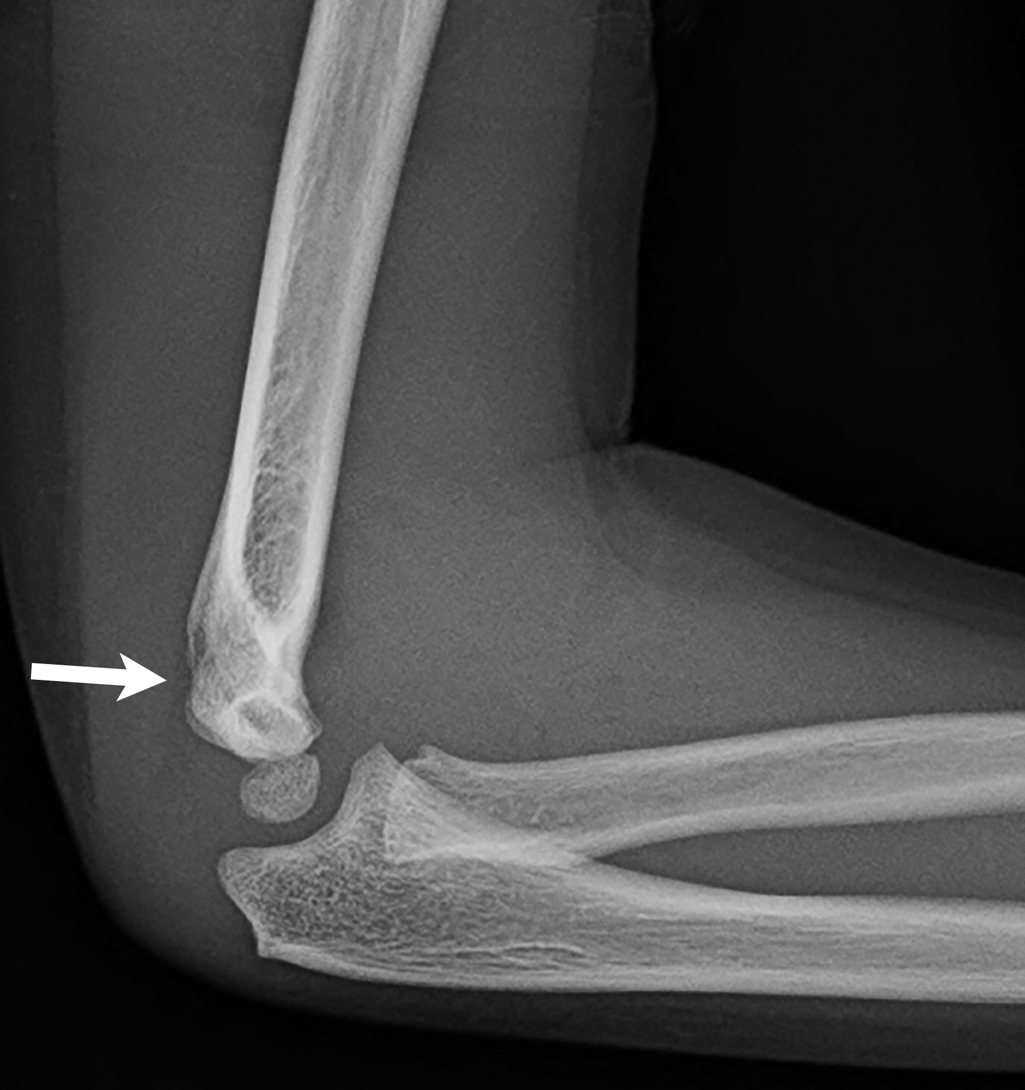

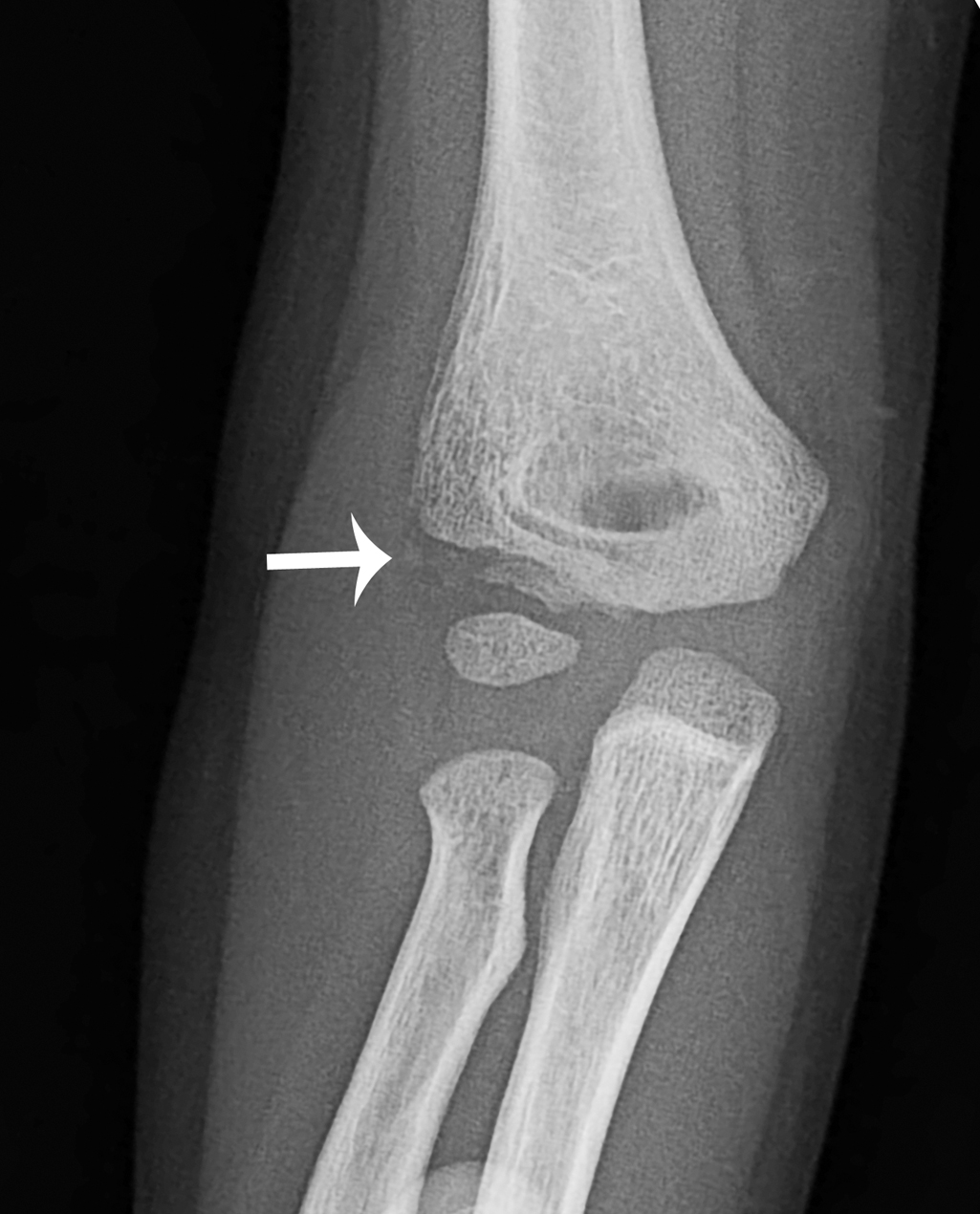

The child initially had two-view imaging of the right elbow. These images demonstrate a fracture of the lateral condyle, not significantly displaced. An elbow joint effusion is present, as evidenced by subtle visualization of the posterior fat pad ( Figs. 53.1 and 53.2 ). Due to the presence of the lateral condyle fracture, an internal oblique view was also obtained. The fracture is again seen, without significant displacement. ( Fig. 53.3 ).

Case conclusion

Pediatric Orthopedics was consulted, and due to the minimal displacement of the fracture, the child was treated with casting immobilization. Follow-up was arranged for 1 week and repeat imaging at that time demonstrated that the displacement had not worsened. He recovered uneventfully.

Lateral condyle fractures

Lateral condyle fractures are among the most common humeral injuries in pediatric patients, second only to supracondylar fractures, accounting for 10%–20% of humeral fractures in this population; however, these are Salter-Harris type IV fractures, with fracture occurring across a metaphyseal and epiphyseal equivalent, the latter being cartilaginous. , Lateral condyle fractures are most commonly caused by falls, and associated injuries include ipsilateral dislocations and ipsilateral upper limb fractures.

There are multiple classification systems used to describe lateral condyle fractures and assist in management guidance. These systems include the Milch, Jakob, Rutherford, and Badelon systems. , These classification systems advocate closed reduction and immobilization as long as the fracture remains stable; otherwise, operative repair is indicated. ,

Management of lateral condyle fractures is determined by the degree of displacement. Complications rates are low in patients who have displacement less than 2 mm. , Therefore, most authors suggest that factures with less than 2-mm displacement can be managed nonoperatively (type I fracture), fractures between 2-mm and 4-mm displacement often exhibit worsening displacement and may need closed reduction and pinning (type II fracture), and fractures greater than 4 mm benefit from open reduction and internal fixation (type III fracture); intact articular cartilage can be useful as a predictor for closed pinning versus open reduction and internal fixation. , ,

Follow-up radiography at 1 week is recommended to assess for fracture displacement. , One study found a displacement rate of almost 15%, usually occurring within the first week following the injury, with nonunion, malunion, and decreased motion as complications. Another study found a displacement rate of around 10%; displacement was detected by subsequent radiographs at follow-up within 1 week in all but one case. Operative intervention was suggested with displacement of more than 2 mm, and follow-up radiography beyond the first week was not indicated until after approximately 3 weeks of immobilization. Treatment compliance can also factor into the management of minimally displaced lateral condyle fractures. While these fractures may not require operative fixation, if noncompliance with follow-up is a concern, reduction and fixation may be indicated to ensure proper healing and maximize return to normal function.

Operative repair is most often accomplished with wiring. , , Most fractures heal well, but there are cases of delayed union or nonunion. In these cases, patients were either treated nonoperatively or had inadequate operative management. , , Malunion has also been reported, and common causes of this complication include inadequate initial reduction or subsequent displacement. , , ,

Medial condyle fractures

Medial condyle fractures are uncommon, comprising 1%–2% of elbow fractures in the pediatric population. , These injuries are Salter-Harris type IV fractures, and nonunion and physeal damage are concerns. , Due to later ossification of the trochlea, these fractures can be difficult to detect radiographically. , Previous literature has suggested that medial condyle fractures are seen primarily in older age children (average age of 9 years old) with minimally displaced fractures occurring in younger children; but a more recent study found an average age of almost 5 years old, with no difference noted between age and severity of the fracture. Interestingly, medial condyle fractures have been reported in patients as young as 6 months of age.

Medial condyle fractures, like lateral condyle fractures, are managed based on degree of displacement and generally heal well. Minimally displaced fractures (less than 2 mm) should be immobilized, and functional results are usually good. , , , Surgical management is usually accomplished with wiring and is recommended for fractures with greater than 2-mm displacement.

Medial epicondyle fractures

Medial epicondyle fractures represent essentially all epicondylar fractures in the pediatric population. , An important feature of these injuries is the association with joint dislocation, which, if present, can incarcerate the displaced epicondylar fragment within the joint either before or after a reduction. ,

Medial epicondyle fractures generally heal well, even in cases of fibrous nonunion (which occurs in up to 90% of patients), with little to no sequelae; traditional management has been immobilization with casting. , , More controversial is the amount of displacement present to indicate operative intervention. Some authors suggest that fractures with less than 5-mm displacement can be managed with immobilization, , and some have suggested nonoperative treatment in patients with fracture displacement up to 15 mm, with great variability in management. , , Incarceration of a medial epicondyle fracture fragment within the joint is an absolute indication for operative intervention to prevent painful sequelae; ulnar nerve palsy (the most commonly affected nerve with these injuries) is not an absolute indication for surgery. , ,

Elbow ossification centers

Knowledge of the order of ossification of the bones of the pediatric elbow is helpful when interpreting elbow imaging. This is especially useful to avoid mistakenly diagnosing an elbow fracture. The six ossification centers of the elbow appear and ossify in a predicable manner based on age. , A helpful mnemonic for remembering this order is CRITOE: ,

| OSSIFICATION CENTER | APPEARANCE AGE | PHYSEAL FUSION AGE |

| C apitellum | 1 year | 14 years |

| R adial head | 4–5 years | 16 years |

| I nternal (medial) epicondyle | 6–7 years | 15 years |

| T rochlea | 8–10 years | 14 years |

| O lecranon | 10 years | 14 years |

| E xternal (lateral) epicondyle | 11 years | 16 years |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree