Emphysema and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

W. Richard Webb

EMPHYSEMA

As defined by the American Thoracic Society, emphysema is “a condition of the lung characterized by permanent, abnormal enlargement of air spaces distal to the terminal bronchiole, accompanied by the destruction of their walls,” but “without obvious fibrosis.” Currently, it is estimated that 2 million people in the United States suffer from emphysema. It is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality.

PATHOGENESIS OF EMPHYSEMA

It is generally accepted that emphysema results from an imbalance in the dynamic relationship between elastolytic and antielastolytic factors in the lung, usually related to cigarette smoking or enzymatic deficiency. Abnormal or unopposed elastase activity is thought to lead to the tissue destruction that is the primary pathologic abnormality present in patients with this disease.

The proposed mechanisms in the development of emphysema in smokers are as follows:

Inhaled tobacco smoke attracts macrophages to distal airways and alveoli (referred to as respiratory bronchiolitis).

The macrophages, along with airway epithelial cells, release chemotactic substances that attract neutrophils and induce them to release elastases and other proteolytic enzymes. Macrophages also release proteases in response to tobacco smoke.

These elastases have the ability to cleave a variety of proteins, including collagen and elastin. Lung elastin normally is protected from excessive elastase-induced damage by alpha-1-proteaseinhibitors (alpha-1-antiproteaseoralpha-1-antitrypsin) and other circulating antiproteinases.

Tobacco smoke tends to interfere with the function of alpha-1-antiprotease.

In combination, these interactions result in structural damage in the distal airways and alveoli, leading to emphysema.

Inherited deficiency in alpha-1-antiprotease similarly results in lung destruction and emphysema when neutrophils release elastases and other proteolytic enzymes in response to pulmonary infection.

CLASSIFICATION OF EMPHYSEMA

Emphysema usually is classified into three main subtypes, based on the anatomic distribution of the areas of lung destruction: (1) centrilobular, proximal acinar, or centriacinar emphysema; (2) panlobular or panacinar emphysema; and (3) paraseptal or distal acinar emphysema. The terms centrilobular, panlobular, and paraseptal are generally accepted and are used to describe these three types of emphysema in the remainder of this chapter. In their early stages, these three forms of emphysema can be easily distinguished morphologically. However, as the emphysema becomes more severe, distinguishing among the types becomes more difficult.

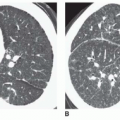

Centrilobular emphysema predominantly affects the respiratory bronchioles in the central portions of acini, and therefore involves the central portion of secondary lobules. It usually results from cigarette smoking and involves mainly the upper lung zones.

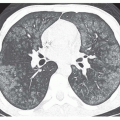

Panlobular emphysema involves all the components of the acinus more or less uniformly, and therefore involves entire secondary lobules. It is classically associated with alpha-1-protease inhibitor (alpha-1-antitrypsin) deficiency, although it also may be seen without protease deficiency in smokers, in elderly persons, distal to bronchial and bronchiolar obliteration, and associated with illicit drug use.

Paraseptal emphysema predominantly involves the alveolar ducts and sacs in the lung periphery, with areas of destruction often marginated by interlobular septa. It can be an isolated phenomenon in young adults, often associated with spontaneous pneumothorax, or can be seen in older patients with centrilobular emphysema.

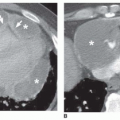

Bullae can develop in association with any type of emphysema, but they are most common with paraseptal or centrilobular

emphysema. A bulla is a sharply demarcated area of emphysema measuring 1 cm or more in diameter and possessing a wall less than 1 mm in thickness. In some patients with emphysema, bullae can become quite large, resulting in significant compromise of respiratory function; this syndrome is sometimes referred to as bullous emphysema. Bullae are most common in a subpleural location, representing foci of paraseptal emphysema associated with air trapping and progressive enlargement.

emphysema. A bulla is a sharply demarcated area of emphysema measuring 1 cm or more in diameter and possessing a wall less than 1 mm in thickness. In some patients with emphysema, bullae can become quite large, resulting in significant compromise of respiratory function; this syndrome is sometimes referred to as bullous emphysema. Bullae are most common in a subpleural location, representing foci of paraseptal emphysema associated with air trapping and progressive enlargement.

Irregular air-space enlargement is an additional type of emphysema that occurs in patients with pulmonary fibrosis; this form of emphysema also is referred to as paracicatricial or irregular emphysema. It commonly is found adjacent to localized parenchymal scars, diffuse pulmonary fibrosis, and in the pneumoconioses, particularly those pneumoconioses associated with progressive massive fibrosis.

DIAGNOSIS OF EMPHYSEMA AND CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

In patients with emphysema, pulmonary function tests usually show findings of chronic airflow obstruction and reduced diffusing capacity. Airflow obstruction in patients with emphysema is due to airway collapse on expiration, resulting largely from destruction of lung parenchyma and loss of airway tethering and support. Abnormal diffusing capacity is due to destruction of the lung parenchyma and the pulmonary capillary bed.

It is important to keep in mind that many patients with emphysema also have chronic bronchitis; both conditions are smoking-related diseases.

The term chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) often is used to describe patients with chronic and largely irreversible airway obstruction, most commonly associated with some combination of emphysema and chronic bronchitis. The term itself indicates some uncertainty as to the exact pathogenesis of the functional abnormalities present; it also may be used to refer to diseases usually associated with airway obstruction, such as emphysema and chronic bronchitis, even if no obstruction is demonstrated on pulmonary function tests.

Respiratory symptoms in patients with COPD usually include chronic cough, sputum production, and dyspnea. Although, cough and sputum production are largely manifestations of chronic bronchitis in patients with COPD, the relative contributions of airways disease and emphysema to respiratory disability often are difficult to determine. Typical pulmonary function abnormalities in emphysema include reductions in the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC), the FEV1, and the diffusing capacity.

Radiographic Findings

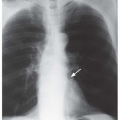

Radiographic abnormalities in patients with COPD are largely the same as those of emphysema. These include increased lung volume and lung destruction (bullae or reduced vascularity). When both findings are used as criteria for diagnosis, a sensitivity as high as 80% has been reported for chest films, although the likelihood of a positive diagnosis depends on the severity of disease. When only findings of lung destruction are used for diagnosis, plain films are only about 40% sensitive.

Although the accuracy of chest radiographs in diagnosing emphysema is controversial, it can be reasonably concluded from the studies performed that moderate to severe emphysema can be diagnosed radiographically, whereas mild emphysema is difficult to detect.

The presence of increased lung volume, or overinflation, is important in making the diagnosis of emphysema on plain radiographs. However, overinflation is an indirect sign of this disease, and findings of increased lung volume are nonspecific. Such findings can be absent in some patients with emphysema but present in patients who have other forms of obstructive pulmonary disease.

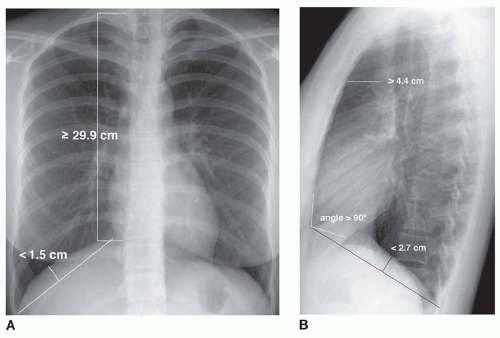

Plain radiographic findings of overinflation (Figs. 24-1 and 24-2; Table 24-1) include the following:

Lung height of 29.9 cm or more, measured from the dome of the right diaphragm to the tubercle of the first rib

Flattening of the right hemidiaphragm on the lateral projection, with a height of less than 2.7 cm measured perpendicular to a line drawn from the anterior to posterior costophrenic angles

Flattening of the right hemidiaphragm on a posteroanterior (PA) radiograph, with the highest level of the dome of the right hemidiaphragm being less than 1.5 cm measured perpendicular to a line drawn between the costophrenic angle laterally and the vertebrophrenic angle medially

Increased retrosternal air space, measuring more than 4.4 cm at a level 3 cm below the manubrial-sternal junction

Right hemidiaphragm at or below the level of the anterior end of the seventh rib

Sternodiaphragmatic angle measuring 90 degrees or more

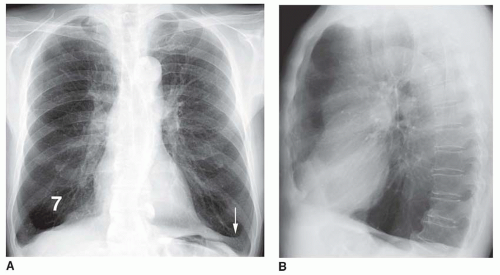

Blunting of the costophrenic angles or visible diaphragmatic slips (i.e., attachments of the diaphragm to the ribs) on the PA view are common findings in markedly increased lung volume; inversion of the hemidiaphragms may be seen on the lateral view (Fig. 24-2).

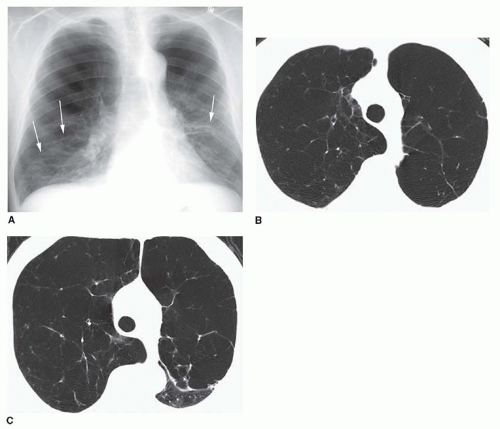

The presence of bullae on chest radiographs is the only specific sign of lung destruction caused by emphysema and usually means that paraseptal or severe centrilobular emphysema is present (Fig. 24-3). However, this finding is uncommon and may not reflect the presence of generalized disease. Bullae usually are visible in the lung periphery, have thin walls, appear lucent, and lung markings are not seen within them. Lung lucency may reflect the presence of bullae when they are not visible as discrete structures.

A reduction in the size of pulmonary vessels or vessel tapering in the lung periphery also can reflect lung destruction in patients with emphysema (see Fig. 24-2), but this finding lacks sensitivity and can be unreliable. Focal absence or displacement of vessels may reflect the presence of bullae (see Fig. 24-3).

TABLE 24.1 Radiographic Findings in Emphysema | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On chest radiographs, centrilobular emphysema usually shows an upper lobe predominance of increased lucency and decreased vascularity (see Figs. 24-3 and 24-4). In panlobular emphysema, lucency and decreased vascularity usually appear to involve the lung uniformly or have a basal predominance (Fig. 24-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree