15 Endosonographic Diagnosis and Treatment Planning in Gastrointestinal Lymphoma The gastrointestinal tract is by far the most frequent site of manifestation for extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs). Primary gastrointestinal lymphomas are today regarded as an independent entity, and there are differences between gastric lymphomas and intestinal lymphomas with regard to etiology, histomorphology, and clinical course. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification, dating from 2002 (Table 15.1), deliberately avoids classification into low-grade and high-grade NHL.1 However, a distinction of this type would still be useful from the clinical point of view. In its present form, the classification does take account of the fact that there is no conclusive evidence for the existence of a sequential development of high-grade lymphomas from low-grade ones. More than 70% of primary gastrointestinal NHLs present as gastric lymphomas. In terms of numbers, marginal-zone B cell lymphomas (MZBCLs) of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCLs) are predominant. The majority of intestinal lymphomas, which represent up to 20–30% of cases, are high-grade B cell and T cell lymphomas. Colonic lymphomas are a rarity, at 2%. Multiple-organ involvement in the gastrointestinal tract is seen in some 6% of cases.2 The etiopathogenetic significance of Helicobacter pylori infection for the development of gastric MZBCL of MALT is well established, with convincing data from epidemiological, morphological, and molecular-biological studies, as well as animal experiments.3 These insights have led to the use of eradication therapy as the treatment of first choice in patients with stage I MZBCL of MALT. Mucosal immuneregulatory changes resulting from untreated gluten-sensitive celiac disease or chronic infections, as well as congenital or acquired immune-deficiency syndromes, are recognized risk factors for intestinal lymphomas. The clinical picture of gastrointestinal lymphomas in nonspecific. It is characterized by abdominal discomfort, pain, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, and manifest or occult bleeding. However, gastric lymphomas are also quite often an incidental finding at endoscopy. In general, it can be stated that complications such as obstruction, perforation, or bleeding are extremely rare in gastric lymphomas but may occur in intestinal lymphomas—which may in part be due to the fact that diagnosing them is more difficult and consequently takes place later. The diagnostic procedure focuses on two aspects: • Precise histological classification, typing, and grading of the lymphoma (MZBCL of MALT, DLBCL with or without MALT components, others (Table 15.1) • Accurate clinical staging These are the two decisive prognostic factors and determinants of treatment.4,5 Careful endoscopic and biopsy diagnosis and accurate staging are the essential prerequisite for adequate treatment. Gastric lymphomas are accessible to endoscopic viewing. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy is therefore of the utmost importance for diagnosis. In view of the nonspecific appearance of gastric lymphomas6 and potential sources of error in diagnostic work-up with endoscopy and biopsy,7 biopsy methods involving what is known as gastric mapping are required. This means: • Taking 8–10 biopsies from suspicious areas • Four-quadrant biopsies from normal-appearing mucosa in the antrum and gastric body • Two biopsies from the fundus • Rapid urease testing in the antrum and gastric body

B cell lymphomas |

Marginal-zone B cell lymphoma of MALT |

Follicular lymphoma (grades I–III) |

Mantle cell lymphoma (lymphomatous polyposis) |

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma with/without MALT-type components |

Burkitt lymphoma |

Immune deficiency-associated lymphoma |

T cell lymphomas |

Enteropathy-associated T cell lymphoma (EATCL) |

Peripheral T cell-lymphoma (non-EATCL) |

The particular difficulty with intestinal lymphomas lies in the limited endoscopic and biopsy access that was possible until very recently. This often made exploratory laparoscopy or laparotomy necessary for diagnostic or therapeutic reasons.

It can be expected that new methods such as double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy (Fig. 15.1) will in the future allow improved noninvasive methods of diagnosing intestinal NHLs. In addition, capsule endoscopy makes it possible to identify the intestinal manifestation expected in some 6% of cases of gastric lymphoma when there is multiple-organ gastrointestinal involvement.2 If a diagnosis of gastrointestinal lymphoma is established, various obligatory or optional (according to Fischbach et al.8) examinations follow to allow assessment of the spread of the lymphoma (“staging”):

• Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) (obligatory)

• Ileocolonoscopy (optional)

• Radiographic small-bowel double-contrast imaging or Sellink magnetic resonance imaging (optional)

• Cervical and abdominal ultrasonography (obligatory)

• Computed tomography of the abdomen (obligatory) and chest (optional in MZBCL of MALT and obligatory in diffuse large B cell lymphoma)

• Cytological and histological assessment of a bone-marrow puncture (optional in MZBCL of MALT and obligatory in DLBCL)

Fig. 15.1 Capsule endoscopy, demonstrating normal mucosa and a follicular lymphoma (arrow).

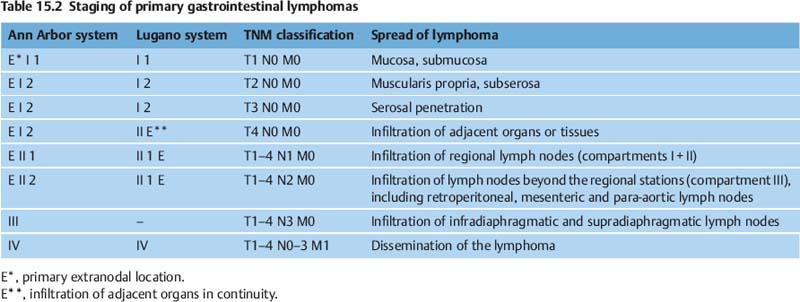

For staging, the Ann Arbor classification is still used, with Musshoffs modification and taking the Radaszkiewicz subclassification of stage I into account (Table 15.2). It would be desirable for the Paris staging system to become established, as it is more modern, is based on the TNM classification, and better reflects the specific characteristics of gastrointestinal lymphomas.9

The prognostic relevance of the subclassification of stages I and II into stages I1, I2, and II1 (Table 15.2) has been confirmed.5 EUS is the only imaging procedure that makes it possible to differentiate the gastric wall layers and that visualizes perigastric lymph nodes. EUS alone is now able to differentiate stages I and II into EI1 (T1 m/sm), EI2 (T2–4) and EII1 (T1–4N1). EUS is therefore an obligatory part of the staging procedure for gastric lymphomas in both the current German S3 guideline “H. pylori

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree