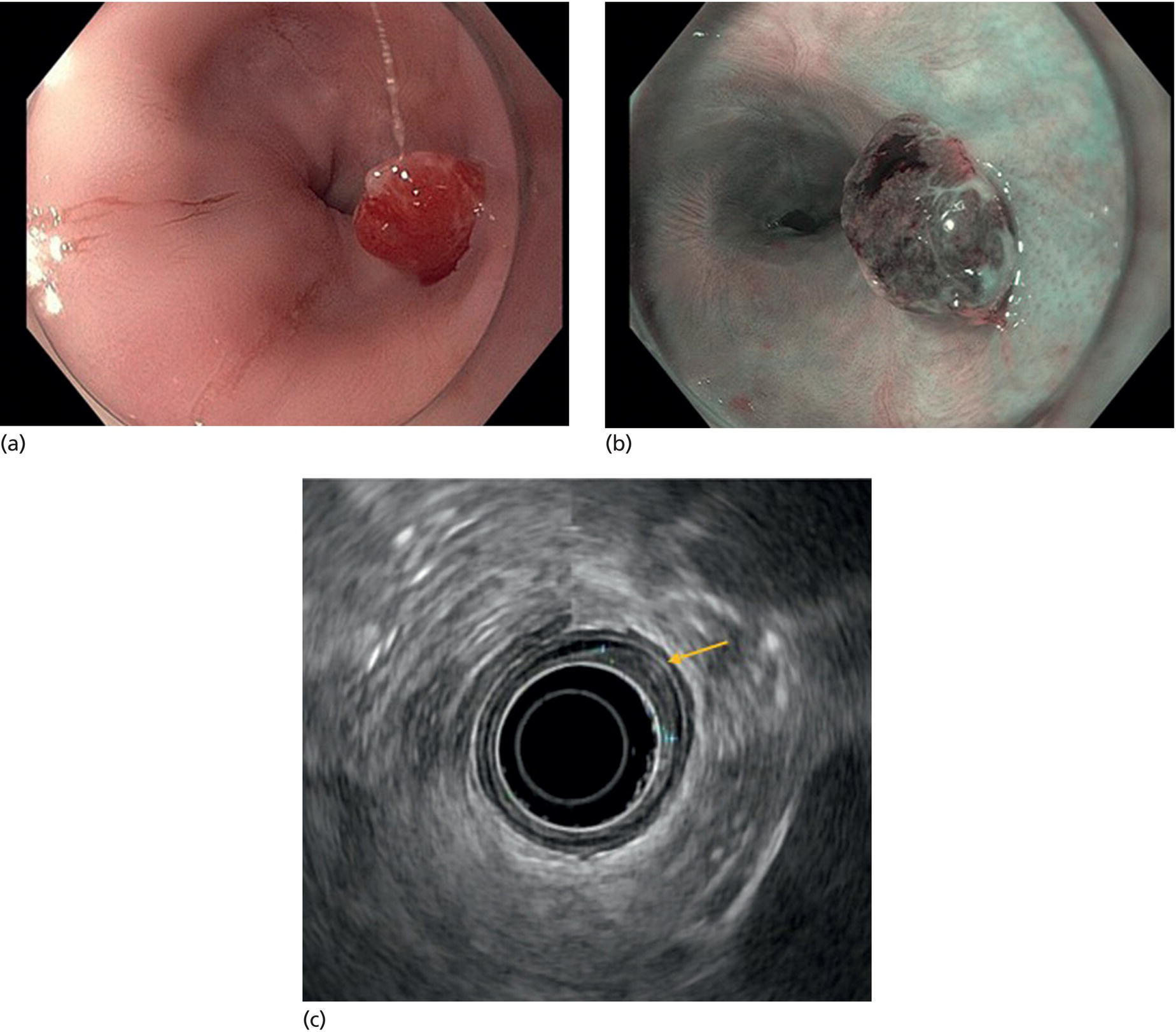

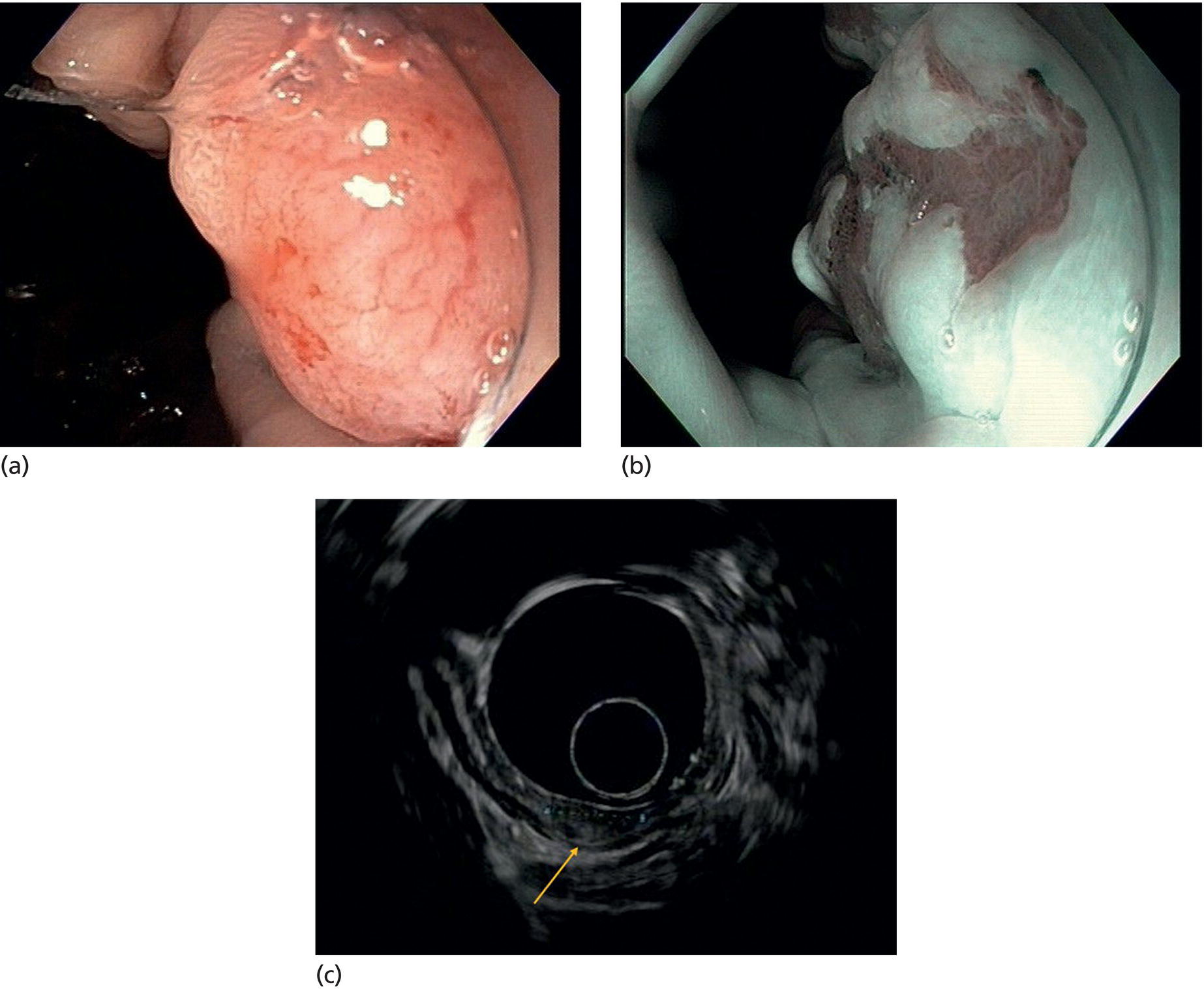

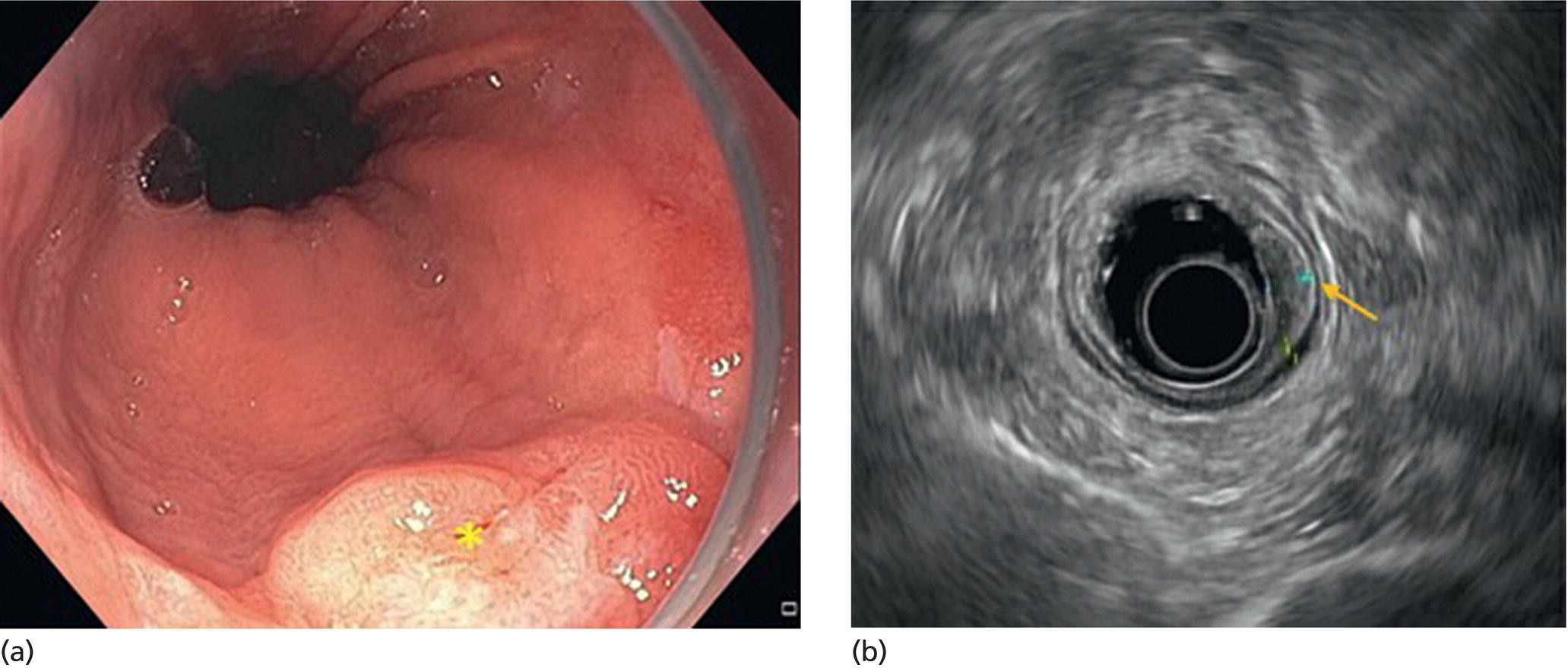

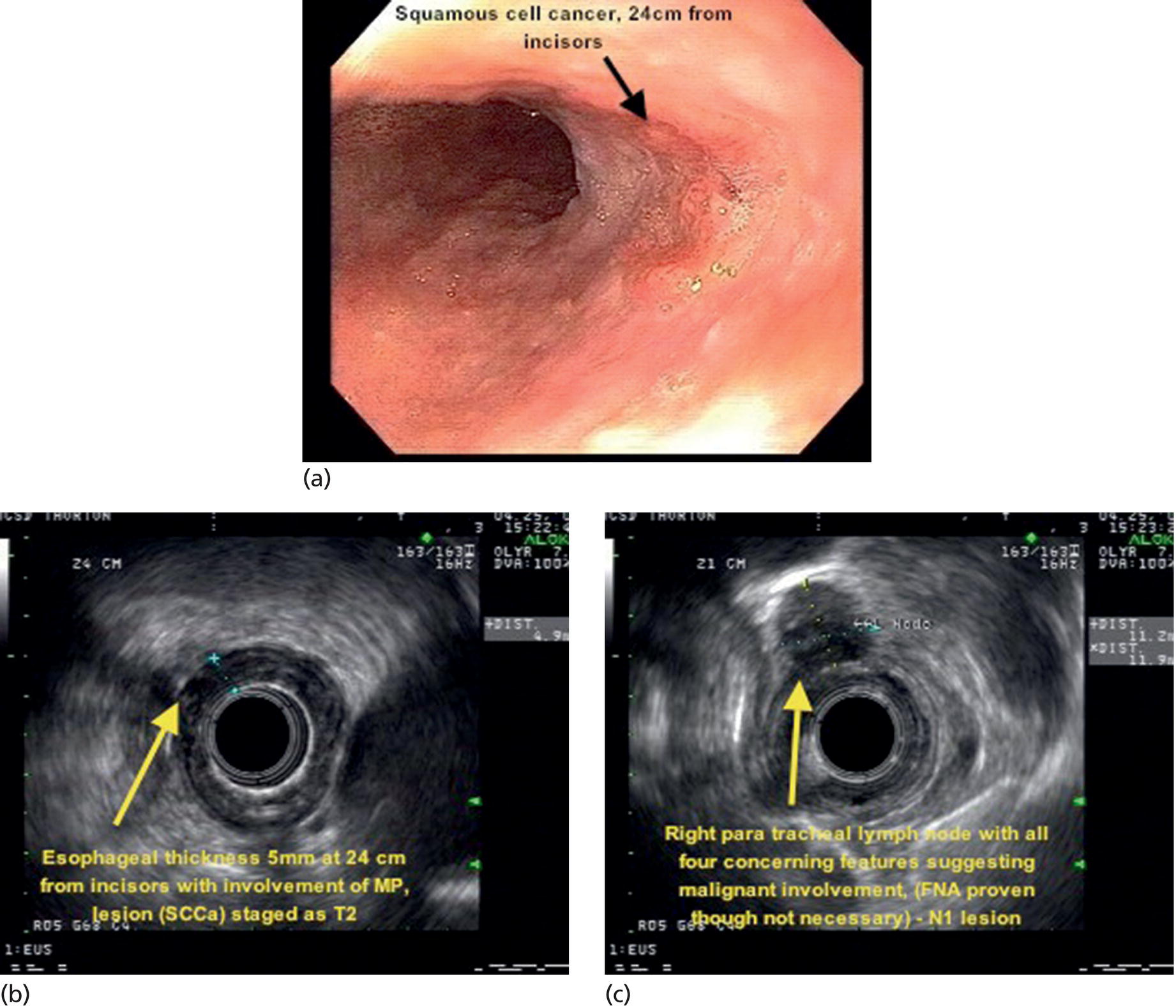

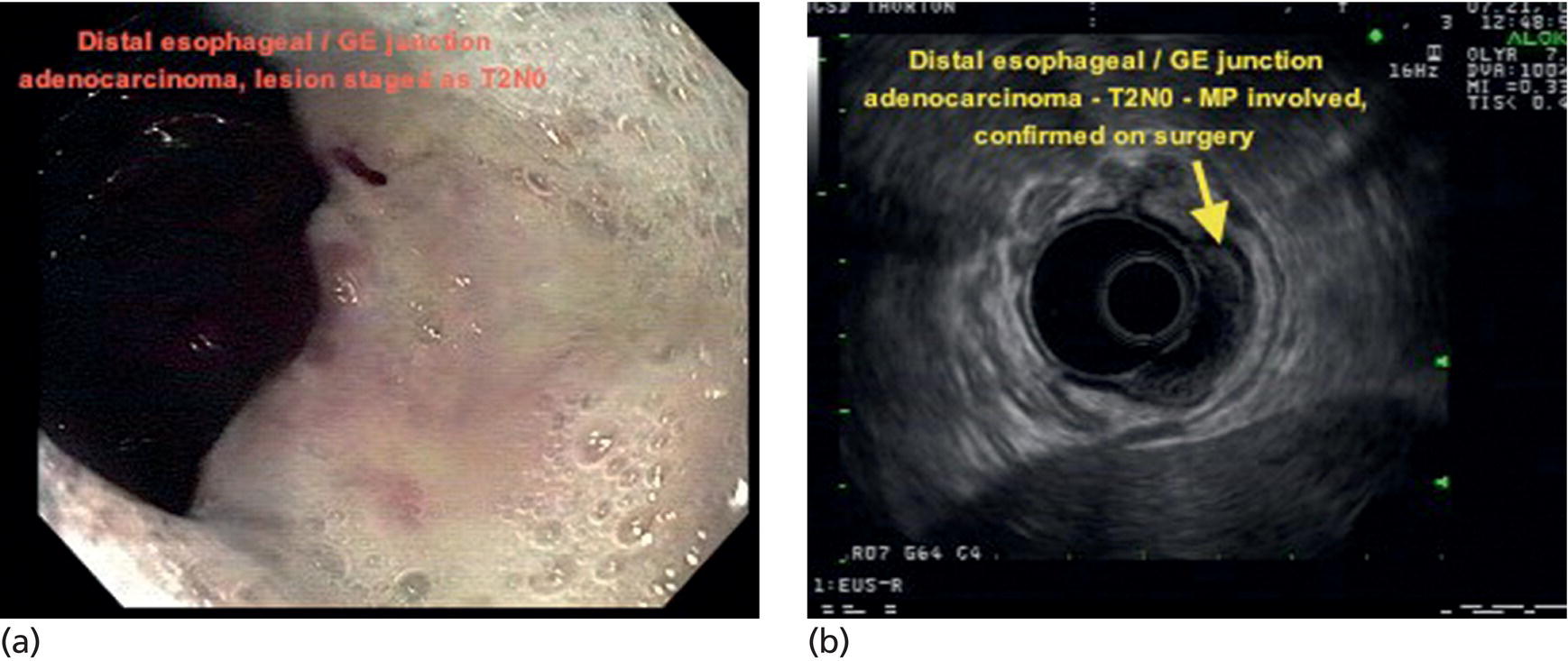

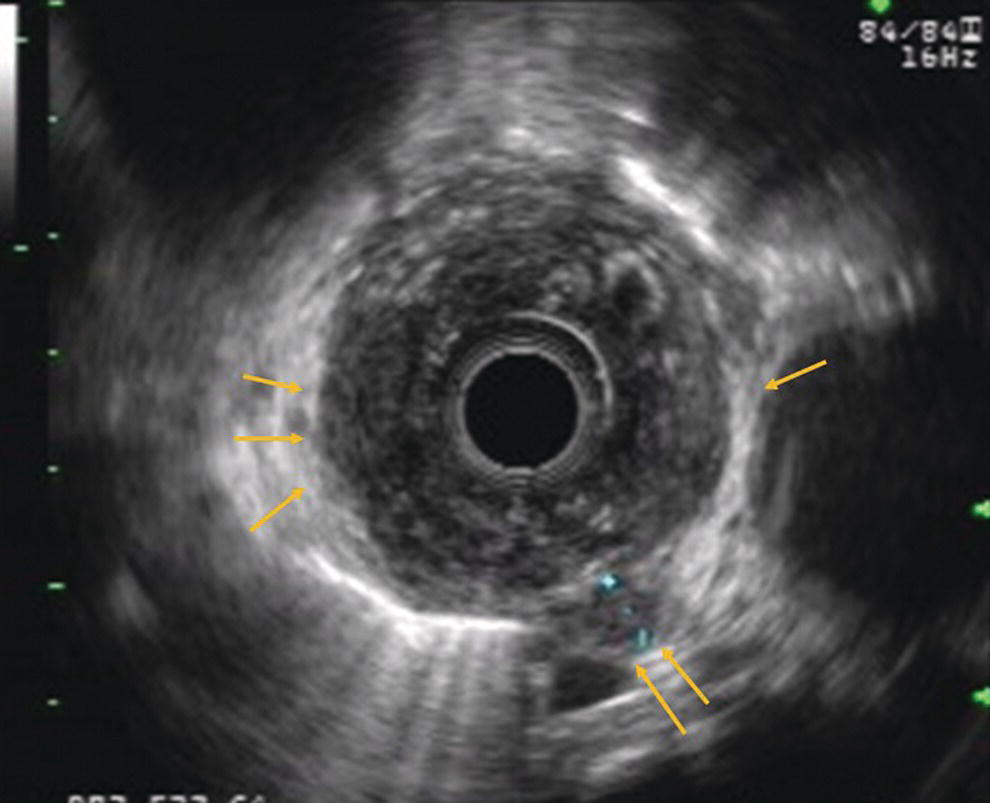

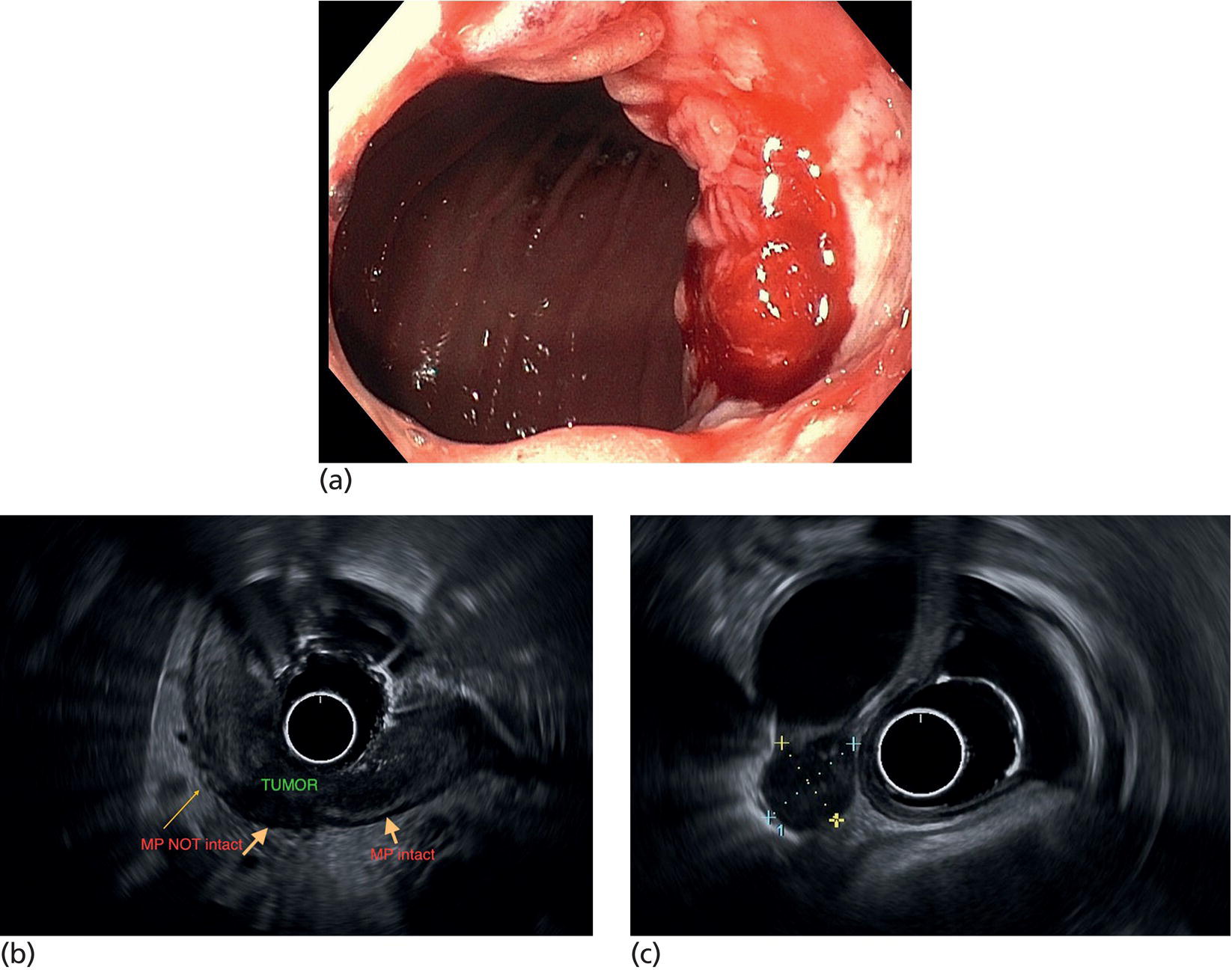

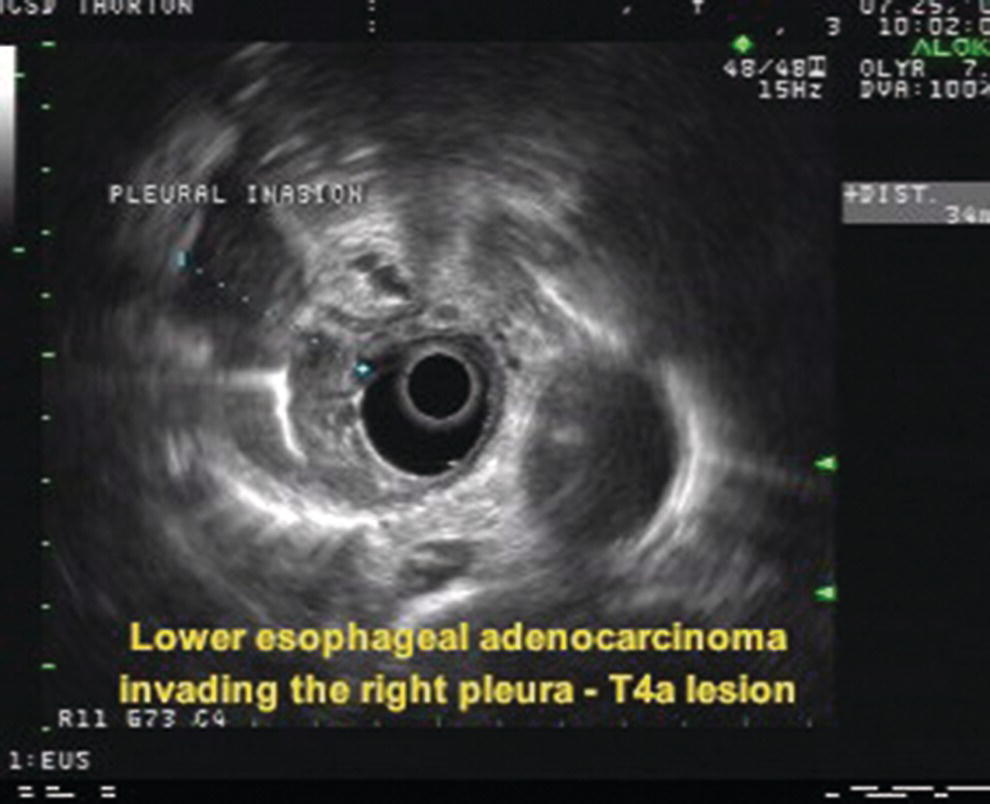

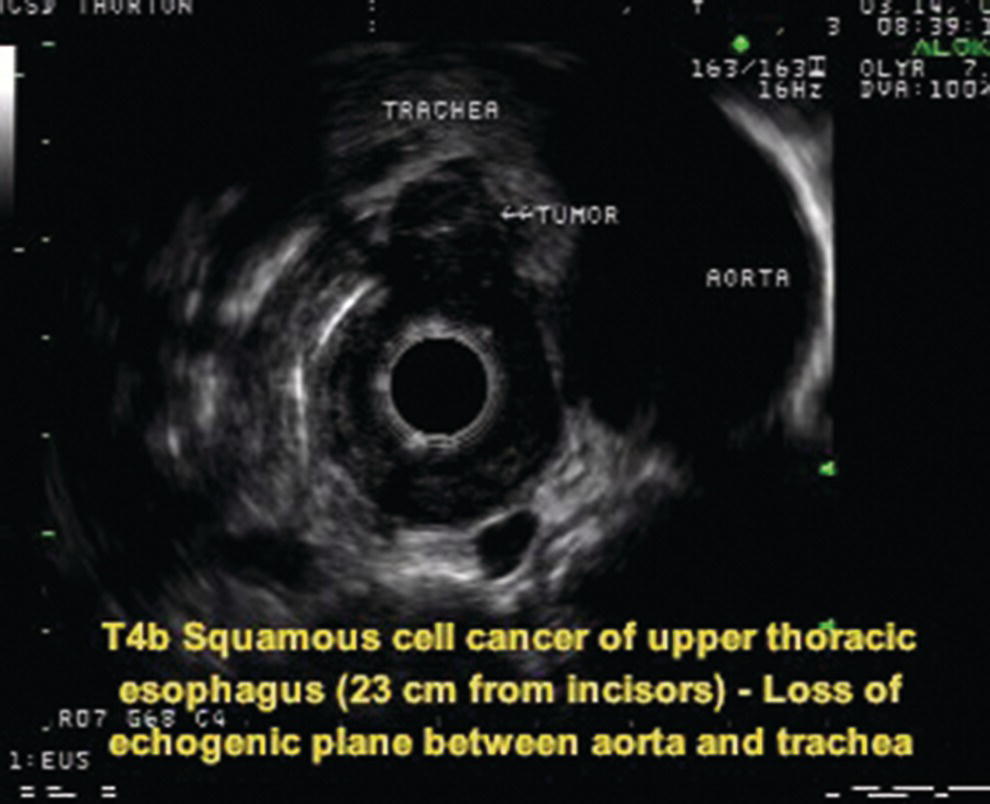

Armen Eskandari and Syed M. Abbas Fehmi Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA In 2018 there were more than 570 000 new cases of esophageal cancer in the world [1]. According to the American Cancer Society, in 2019, 17 650 new cases of esophageal cancer will be diagnosed in the USA with an attributable 16 080 deaths. The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma continues to rise in the USA, albeit at a slower rate. In the last 15 years, the role of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has evolved in the management of esophageal cancer, with EUS currently essential for accurate locoregional staging and addressing the key management question of operability. The eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) includes clinical, pathologic and neoadjuvant staging groups to facilitate staging in an increasing number of patients undergoing chemoradiation prior to esophagectomy and in patients who may not undergo esophagectomy at all due to advanced disease (Table 9.1). The important changes affecting the endosonographer in daily practice include a change in the definition of tumor location from the upper border of the tumor in the seventh edition to the epicenter of the tumor in the eighth edition. The location of the primary tumor is defined by the epicenter of cancer in centimeters from the incisors (cervical esophagus 15 cm to <20 cm; upper thoracic esophagus 20 cm to <25 cm; middle thoracic esophagus 25 cm to <30 cm; and lower esophagus 30–40 cm). In addition, cancers involving the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) whose epicenter is within 2 cm of the cardia are stage grouped similar to lower thoracic esophageal cancer. EGJ tumors with their epicenter located more than 2 cm into the proximal stomach are staged as stomach cancers, as are all cardia cancers not involving the EGJ. The eighth edition of the TNM classification is shown in Table 9.1. As in the previous edition, stage groupings are separate for squamous cell cancer and adenocarcinoma; however, the criteria for T, N, and M stage designation for the two histologic types is similar. The locoregional staging of esophageal cancer is most accurately done by EUS when compared to any other imaging modality, including computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Accurate staging helps predict the prognosis, optimize management strategy, and provides a standard platform for comparison of patients for research purposes. It is recommended to perform a standard upper endoscopy prior to EUS examination. The endoscopy report should mention the location of the tumor, presence and degree of obstruction, presence of skip lesions, and whether EUS staging was incomplete due to obstruction precluding passage of the echoendoscope. EUS can examine the different wall layers of the esophagus, which forms the basis for its superiority over other imaging modalities. The reported accuracy of EUS for T staging is 80–90%. Accuracy for distinguishing T3 or T4 disease from T1 or T2 disease is better than distinguishing T1a or T1b from T2 disease. In our practice, the role of EUS in the setting of Barrett’s esophagus for Tis lesion (defined as high‐grade dysplasia) is to exclude periesophageal lymphadenopathy or a mass. T1 lesions can be divided into T1a or T1b depending on whether tumor is limited to mucosa (Figure 9.1) versus submucosal invasion (Figures 9.2 and 9.3). If the tumor is observed to invade the fourth layer (muscularis propria or proper muscle layer), the tumor is classified as T2 (Figures 9.4 and 9.5). When the tumor invades through the muscularis propria into the adventitia, it is classified as a T3 lesion (Figures 9.6 and 9.7, and Video 9.1). The T4 stage has been revised in the updated guidelines. In addition to involvement of pleura, diaphragm, and pericardium, tumors that are found to invade the azygos vein and peritoneum are now also considered T4a and hence potentially resectable (Figure 9.8) Involvement of the aorta, trachea, and vertebral body indicates T4B disease which is considered unresectable (Figure 9.9). Table 9.1 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging of esophageal cancer, 2017 (eighth edition). For N staging, EUS has an accuracy of 75–80%. Endoscopic ultrasound‐guided fine needle aspiration (EUS‐FNA) can improve accuracy, but care must be taken that the needle does not penetrate the area of the tumor in order to prevent false‐positive results. The positive predictive value of four subjective endosonographic features of lymph nodes (round, hypoechoic, sharp edges, and size 1 cm or more in short axis) is about 90%. If these are present, there is less need to do FNA. In the 2017 TNM classification, the N component has been subclassified according to the number of regional lymph nodes containing metastasis (N1 indicating metastases in one to two regional nodes; N2 metastases in three to six nodes; and N3 metastases in seven or more). Additionally, celiac lymphadenopathy distant from the primary tumor site is no longer considered distant metastasis in the new classification. M1 disease is now defined as metastasis to non‐regional lymph nodes or distant sites. EUS can visualize liver metastases of less than 1 cm or even malignant ascites, and EUS via FNA can provide endoscopic opportunity for providing a tissue diagnosis for either of these findings. It is important to note that edema, cellular infiltration, and neoplastic masses can produce an endosonographic image of a thickened esophageal wall upstaging early disease. EUS is considerably less accurate (40%) for restaging of disease after chemoradiation therapy secondary to the associated fibrosis and inflammation. Recent studies suggest that FNA of even benign‐appearing lymph nodes may increase the sensitivity (50% vs. 75%) and specificity (78% vs. 100%) of qualitative EUS [2] in this setting. The sensitivity of EUS in detecting pathologic complete response (ypCR) has been reported from as low as 10% to as high as 96.4% [3,4]. The management for early disease may differ somewhat between institutions, but the treatment outcome for patients is highly stage dependent. Therefore, in most circumstance a multimodal approach to preoperative staging is adopted which includes cross‐sectional imaging with CT or hybrid PET/CT. With increasing use of PET/CT, the role of EUS has decreased in some practices. However, a recent study on 279 patients who received upfront PET and were also staged with EUS showed that EUS impacted the management plan in 28.7% of patients including change in radiation field in 22.6%, curability in 1.8%, and lymphadenectomy in 17.2%. Additionally, FNA provided definitive information regarding lymph node status in 7.5% [5]. For early‐stage disease, operability is the key question that heavily depends on accurate T staging by EUS. Currently, for Tis or T1a disease in the absence of any lymph nodes, the endoscopic approach is usually the preferred option. Even for T1b disease, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) has usually been done to confirm submucosal invasion when endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is not available. The role of ESD is rapidly evolving for early/superficial disease in the USA and is well established outside the USA (e.g. Japan and Europe). A recent practice update from the American Gastroenterology Association recommends consideration of ESD in selected patients with Barrett’s esophagus if they have a large or bulky area of nodularity, confirmed or suspicious submucosal invasion, or recurrent dysplasia. In some poor surgical candidates, ESD or other aggressive endoscopic therapy like cryoablation may also be offered. Usually for T2 disease with no obvious lymph node involvement, surgery is done. However, if lymph node involvement is suspected or it is T3 disease, neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgery is usually the preferred option. T4b disease is usually unresectable with no surgical opportunity for cure. The use of neoadjuvant therapy with subsequent surgery is becoming increasingly popular; this in turn poses the difficulty of restaging patients after neoadjuvant therapy. As described earlier, EUS performs poorly in patients who have undergone neoadjuvant therapy. Figure 9.1 Distal esophageal adenocarcinoma shown to be T1a on pathology. (a) White light and (b) narrow band imaging; (c) EUS image shows intact submucosa (yellow arrow). The endosonographer must be familiar with the patient’s history (specifically the presence and degree of dysphagia) and the impact of EUS findings on management. It is advisable to perform an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) before EUS to confirm the extent of the lesion (for accurate staging), assess patency of the lumen (hence, the for need of dilation), and report skip lesions. In some centers, surgery is being offered for staging with an initial approach being minimally invasive; in most centers, though, EUS is used. The radial array echoendoscope is most frequently used due to its 360‐degree imaging and ease of use. The standard technique is to do multiple pull‐backs from the stomach into the proximal esophagus, paying close attention to the wall layers and periesophageal lymph nodes. Effort should be made to evaluate the liver for metastasis. For stenotic tumors not allowing passage of the usual 13‐mm tip echoendoscopes, dilation to 15 mm or 45 Fr is usually required. Risks of dilation need to be weighed against perceived benefits of any additional information gained by passing the endoscope distal to the stenosis. Some strategies include use of thin non‐optic probes or endobronchial scopes versus embedding the tip of a regular EUS scope in the proximal aspect of tumor and trying to obtain as much information as possible (T3 lesion or N1). Non‐optic probes with high frequency can also be used to distinguish T1a and T1b lesions with high accuracy. However, with newer electronic EUS scopes and improved processors, imaging has improved so that high‐frequency probes may not be routinely used. In addition, EMR is being increasingly utilized for better histologic assessment for mucosal versus submucosal involvement. When an obstructing tumor precludes passage of the echoendoscope, the report should mention that the examination may not be accurate. Figure 9.2 T1b adenocarcinoma in a background of Barrett’s esophagus at the gastroesophageal junction. (a) High‐definition white light image shows irregular pit pattern. (b) Narrow band imaging of the same lesion. (c) EUS image with yellow arrow showing intact muscularis propria. Figure 9.3 (a) T1b adenocarcinoma at the gastroesophageal junction with central depression shown by asterisk. (b) EUS image showing submucosal invasion but no involvement of muscularis propria shown by yellow arrow. Figure 9.4 (a) T2N1Mx lesion, squamous cell cancer with ulceration 24 cm from incisors shown by yellow arrow. (b) EUS image showing invasion of muscularis propria (MP) but not through the MP, shown by arrow. (c) Malignant‐appearing paratracheal lymph node also observed and marked by arrow. This has all four concerning features suggesting malignant involvement (fine needle aspiration [FNA] proven though not necessary). Since a total of two or less lymph nodes are observed during exam, lesion classified as N1 according to the eighth edition of the AJCC classification system. Figure 9.5 (a) T2N0Mx lesion, adenocarcinoma of lower thoracic esophagus involving gastroesophageal (GE) junction, marked by arrow. (b) EUS image showing invasion of muscularis propria (MP) but not through the MP, marked by arrow. Figure 9.6 T3N3Mx lesion, adenocarcinoma involving the lower thoracic esophagus, lesion invading through the muscularis propria (MP) into the periesophageal fat marked by three arrows. Note malignant‐appearing lymph node (LN) marked by double arrows; a total of eight such LNs were observed during the exam, making this an N3 lesion (according to the eighth edition of the AJCC guideline). Note also the intact plane between the lesion and aorta marked by single arrow. Figure 9.7 (a) T3N1Mx adenocarcinoma with friable mass at the gastroesophageal junction. (b) EUS image showing lesion invading through the muscularis propria (MP) into the periesophageal fat, marked by arrow. (c) Round, hypoechoic, symmetrical lymph node larger than 10 mm suggestive of malignancy. Figure 9.8 T4a lesion, adenocarcinoma in lower thoracic esophagus invading through the muscularis propria and the periesophageal fat into the right pleura (note made of loss of echogenic plane between lesion and right pleura). According to the eighth edition of the AJCC guideline, this is a potentially resectable lesion staged as T4a. Figure 9.9 T4b lesion, squamous cell cancer in upper thoracic esophagus invading through the muscularis propria and the periesophageal fat into the aorta and trachea (note made of loss of echogenic plane between lesion and the aorta and trachea). According to the eighth edition of the AJCC guideline, this is an unresectable lesion staged as T4b.

9

Esophageal Cancer

Introduction

Updated American Joint Committee on Cancer staging guidelines for esophageal cancer 2017 and implications for endosonographers

Role of EUS in staging of esophageal cancer

TX

Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0

No evidence of primary tumor

Tis

High‐grade dysplasia

T1

Tumor invades the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa

T1a

Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae

T1b

Tumor invades the submucosa

T2

Tumor invades the muscularis propria

T3

Tumor invades the adventitia

T4

Tumor invades adjacent structures

T4a

Resectable tumor invading the pleura, pericardium, diaphragm, azygos vein and peritoneum

T4b

Unresectable tumor invading the other adjacent structures such as aorta, vertebral body, trachea, etc.

NX

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

N0

No regional lymph node metastasis

N1

Metastasis in 1–2 regional lymph nodes

N2

Metastasis in 3–6 regional lymph nodes

N3

Metastasis in 7 or more regional lymph nodes

M0

No distant metastasis

M1

Distant metastasis

Limitations

Impact of EUS staging on management

Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree