Facial Trauma

Lindell R. Gentry

L. R. Gentry: Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, Madison, Wisconsin 53792-3252.

The incidence and severity of facial trauma have greatly increased during the last few decades because of the increased use of high-speed travel modes. Evaluation of patients with facial trauma requires special attention to the clinical situation, because many such patients also have injuries of other body systems. In all unstable patients, definitive evaluation of facial injury is best delayed for a few hours until the more urgent injuries have been treated.

Thin-section high-resolution computed tomography, over the last two decades, has become the most important diagnostic study for evaluation of traumatic facial injury.1,2 Because computed tomography (CT) alone can answer the majority of clinical problems, it has replaced other diagnostic studies as the preferred initial examination for patients with facial trauma.1 Conventional radiography is now relegated to imaging of very simple types of fractures. Magnetic resonance imaging is currently viewed as an ancillary diagnostic procedure reserved for assessment of specific soft-tissue complications of trauma, such as intraorbital hematoma, optic nerve injury, and vascular injuries.

The facial skeleton comprises numerous thin bony struts that are oriented in multiple planes (axial, coronal, sagittal).1 These struts are oriented in this pattern so that the face is protected from a variety of forces. There are many different types of fractures in the upper and lower face.

FRONTAL SINUS FRACTURES

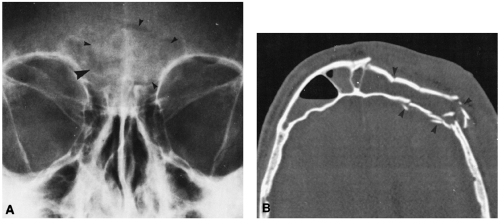

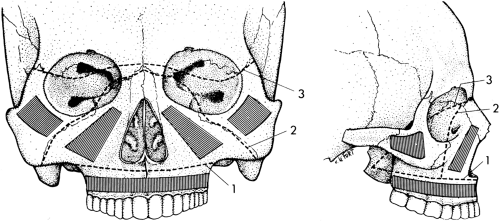

Frontal sinus fractures can be caused by localized trauma to the frontal sinuses.1,2 More frequently, the frontal sinuses are injured when fractures in other areas (cranial vault, anterior skull base, lower face) propagate into these sinuses. Fractures may be linear, comminuted, or complex. Linear fractures usually involve only the anterior sinus wall. Complex frontal sinus fractures are commonly associated with other facial trauma and consist of fractures of both the anterior and posterior walls (Fig. 37-1). Signs of frontal sinus fractures include fluid levels, sinus opacification, orbital emphysema, and intracranial pneumocephaly. Frontal sinus fractures and their fragments are best demonstrated on axial CT scans.1,2

ORBITAL FRACTURES

Fractures of the orbit occur as isolated injuries or in combination with other facial or cranial fractures. They may be simple or complex.1,2,3

Simple Fractures

Simple fractures are of two kinds: those that involve only the orbital rim, and those that involve only an orbital wall (blowout type). Because the orbital rim is the strongest part of the orbit, isolated rim fractures are uncommon.

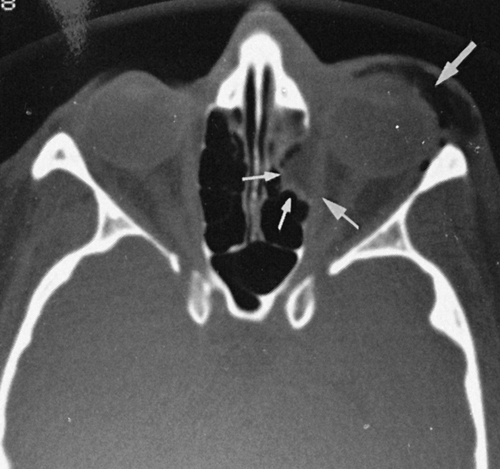

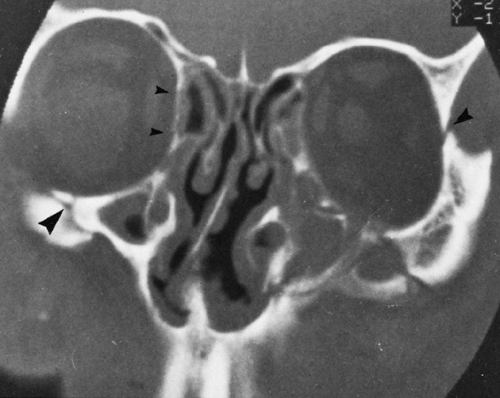

Blowout fractures are thought to be produced by a sudden increase in intraorbital pressure caused by violent impact to the anterior aspect of the orbit by a rounded object (e.g., fist, ball). This is thought to cause an increase in intraorbital pressure, resulting in a blowout fracture of the weaker portions of the orbital walls. The walls that are most susceptible to blowout fracture are the inferior and medial orbital walls. A blowout fracture is considered pure if only the orbital wall is fractured and impure if there is a coexistent fracture of the orbital rim.1,2,3

Radiographic findings in blowout fractures include floor disruption, ipsilateral sinus opacification caused by hemorrhage, and orbital emphysema resulting from interruption of an adjacent sinus wall.1,2,3 CT is required to precisely delineate the fractures and assess for complications (Figs. 37-2, 37-3, and 37-4).

The major complication of a blowout fracture is muscle entrapment. The inferior rectus and/or inferior oblique muscles can be entrapped in floor fractures, and medial rectus entrapment can occur in medial-wall fractures.2,3 Fractures

that involve the infraorbital foramen may produce anesthesia over the distribution of the infraorbital nerve. Enopthalmos, a posterior displacement of the globe in the orbit, is caused when a large amount of orbital fat is displaced into the sinuses at the time of the fracture.2,3

that involve the infraorbital foramen may produce anesthesia over the distribution of the infraorbital nerve. Enopthalmos, a posterior displacement of the globe in the orbit, is caused when a large amount of orbital fat is displaced into the sinuses at the time of the fracture.2,3

Complex Fractures

Complex orbital fractures are those that involve multiple facial struts. All suspected complex fractures should be imaged with CT. Small fracture fragments and soft-tissue complications cannot be demonstrated adequately by conventional techniques (Figs. 37-5 and 37-6).2,3 The complex fractures that involve the orbit are the Le Fort II and III fractures (Fig. 37-4), nasofrontoethmoidal fractures (Fig. 37-7), and zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) or “tripod” fractures.

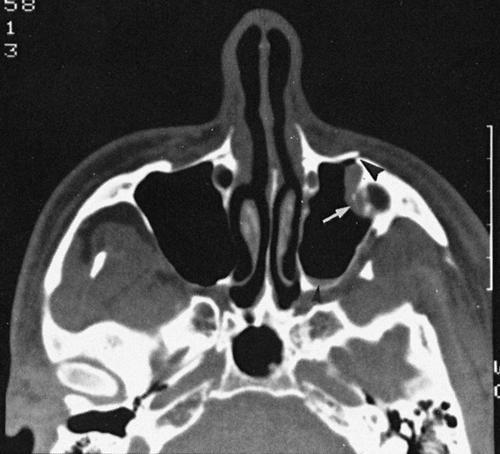

Nasofrontoethmoidal complex fractures typically involve the medial walls of the orbit. These fractures are caused by midline blunt trauma to the upper nasal area and the base of the frontal sinuses. This results in a posterior displacement of the thin bony struts in this region into the anterior aspect

of the ethmoid sinuses (Fig. 37-7). The medial orbital walls (lamina papyracea) usually are fractured and displaced into the medial aspect of the orbit. The structures most frequently injured are the medial rectus muscles, the optic nerves, and the frontal sinus drainage pathways. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea is also a common complication resulting from injury of the cribriform plate.2.

of the ethmoid sinuses (Fig. 37-7). The medial orbital walls (lamina papyracea) usually are fractured and displaced into the medial aspect of the orbit. The structures most frequently injured are the medial rectus muscles, the optic nerves, and the frontal sinus drainage pathways. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea is also a common complication resulting from injury of the cribriform plate.2.

The bony struts that usually are fractured with the ZMC fracture are the inferior orbital wall and rim, the lateral orbital wall and rim, the anterior and posterolateral maxillary sinus walls, the lateral wall of the orbit, and the zygomatic arch. Complications related to ZMC fractures are similar to those that occur with blowout fractures. CT is the best study to demonstrate the fractures associated with this type of injury, although conventional films can demonstrate the zygomatic arch component of the fracture (Fig. 37-8).1,2,3,4

The locations of orbital involvement in Le Fort II and III injuries are different (Fig. 37-9). In the Le Fort II fracture complex, the anteromedial portion of the orbit is damaged, whereas both the medial and lateral aspects of the orbit are injured in Le Fort III fractures (see Fig. 37-4). These fractures are discussed in a later section.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree