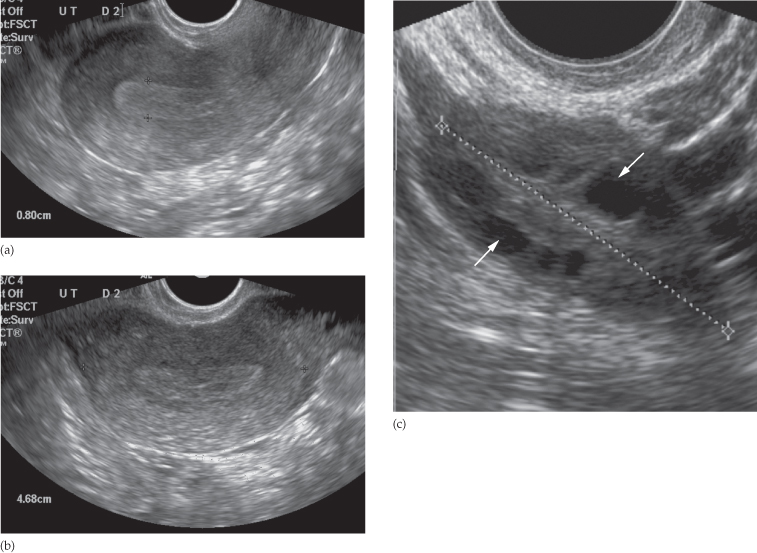

Fig. 9.2 Normal transvaginal ultrasound scan. (a) Longitudinal section through the uterus. Note the echogenic endometrial stripe between the measurement calipers. (b) Transverse section through the uterus. (c) Normal ovary. Several normal follicles are seen (arrows).

The ovaries are suspended from the broad ligament and usually lie lateral to the uterus near the pelvic side walls. During childbearing years, the ovaries measure 2.5–5 cm in greatest diameter, but after the menopause they atrophy. The endocrine changes occurring during the menstrual cycle have a great effect on the appearance of the ovaries. During the early phase, several cystic structures are seen, representing developing follicles (Fig. 9.2c). Around the eighth day of the cycle, one follicle becomes dominant and may reach 2–2.5 cm in diameter prior to ovulation. At ovulation, the follicle ruptures and immediately decreases in size giving rise to the corpus luteum, which degenerates if there is no intervening pregnancy. By observing these changes it is possible to determine whether an infertile woman is ovulating.

Computed Tomography

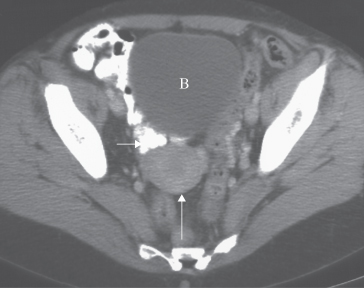

Multislice CT of the pelvis may be optimized with the use of oral contrast (water or dilute iodine-based contrast) given 1 hour prior to pelvic imaging to aid the differentiation of bowel loops from adnexal structures. Intravenous contrast medium may help to differentiate between vessels and lymph nodes, and to assess the enhancement pattern of a mass. Viewing on coronal and sagittal reformatted images is also helpful. The vagina is seen as a linear structure between the urethra and rectum. Immediately above the vagina, the cervix is seen as a rounded soft tissue structure approximately 3 cm in diameter. The body of the uterus (Fig. 9.3) merges with the cervix and its precise appearance depends on the lie of the uterus. The endometrial lining cannot be fully assessed on CT. The fallopian tubes and broad ligaments are usually not visible and the ovaries may not be identified. The parametrium is of fat density, the interface with the pelvic musculature being clearly visible. The uterus may be surrounded by loops of bowel.

Fig. 9.3 Normal uterus (long arrow) in a 49-year-old patient, on CT, following intravenous contrast enhancement. Note the oral contrast medium within loops of the small bowel (short arrow). B, bladder.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

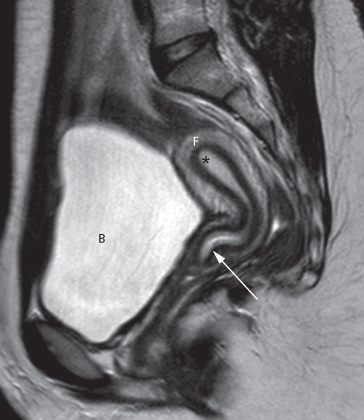

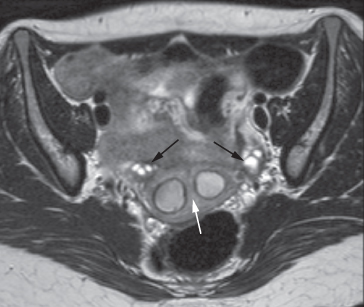

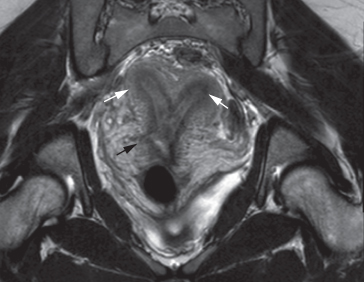

Pelvic anatomy is very well demonstrated because of the excellent soft tissue contrast afforded by MRI. The patient may be given a muscle relaxant to reduce movement artefacts from the bowel. Images are usually taken in the axial and sagittal planes but may be supplemented by oblique images, particularly for examination of the cervix or endometrium. Axial images give anatomical appearances similar to CT. T2-weighted sagittal images show the vagina and cervix in continuity with the body of the uterus. The zonal anatomy of the uterus is best demonstrated on T2-weighted images, with the endometrium having a high signal intensity, the adjacent inner myometrium (junctional zone) a low signal intensity, and the myometrium an intermediate signal intensity (Fig. 9.4). The cervix may be predominantly low in signal intensity. Variations of uterine anatomy are well delineated on MRI (Figs 9.5 and 9.6). The ovaries are of intermediate signal intensity and often contain multiple high signal follicles on T2-weighted images (Fig. 9.5). The broad ligaments can also be identified.

Fig. 9.4 Normal uterus on sagittal T2-weighted MRI. The endometrium (*) returns a high signal intensity. The cervix (white arrow) is in continuity with the lower uterine body. B, bladder; F, uterine fundus.

Fig. 9.5 Axial MRI of a septate uterus, an anatomical variant. The endometrial cavity is divided into two compartments by a septum of myometrium (white arrow). Note the normal ovaries bilaterally (black arrows).

Fig. 9.6 Oblique coronal T2-weighted MRI of a bicornuate uterus, with two divergent cornu (white arrows). The scar from a previous caesarean section is also seen (black arrow).

Positron Emission Tomography/computed Tomography

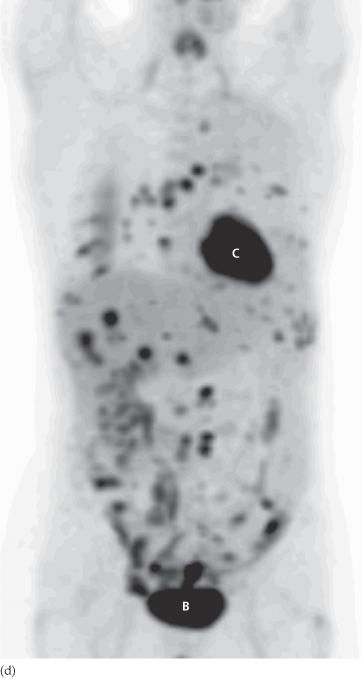

In selected cases, the extent and distribution of gynaecological cancer may be assessed using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET)/CT. This technique is particularly helpful in detecting disease that has metastasized beyond the pelvis (see Fig. 9.9d). In addition, some centres are using the technique to assess response to chemotherapy.

Gynaecological Pathology

Patients attending for pelvic imaging may present with non-specific symptoms of lower abdominal discomfort or pain, a sensation of bloating, with abnormal vaginal bleeding or a pelvic mass. Pelvic imaging may also be undertaken for the investigation of infertility. Ultrasound is the initial investigation in most cases.

Pelvic Masses

Ultrasound, CT and MRI will be abnormal in virtually any patient in whom a mass can be felt on physical examination. With ultrasound, it is possible to tell whether the mass is cystic or solid. In some cases, the characteristics of the adnexal cyst or mass may indicate whether the lesion is benign in nature or likely to be malignant. However, in some cases, this distinction cannot be made on ultrasound alone and MRI may be helpful in further characterization. CT is predominantly used to demonstrate the extent of disease in the abdomen in cases of malignant disease. A limitation of imaging, particularly ultrasound and CT, is that sometimes it is not possible to determine from which organ the mass arises; an ovarian mass that lies in contact with the uterus may appear similar to a mass arising within the uterus and vice versa. MRI, which may be performed in any scan plane, may be used to help make the distinction.

Ovarian Masses

Ovarian Cysts

Sometimes a follicle or corpus luteum persists as a follicular or corpus luteum cyst, both of which are easily recognized by ultrasound, CT or MRI (Fig. 9.7). Follicular cysts are mostly asymptomatic and regress spontaneously. Corpus luteum cysts are most often seen in the first trimester of pregnancy; they usually resolve, but may rupture or twist. Haemorrhage into both types of cyst may occur and gives a characteristic appearance on ultrasound.

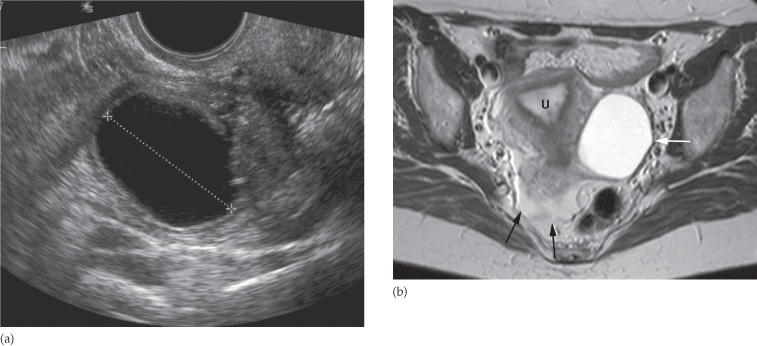

Fig. 9.7 Ovarian cyst. (a) Longitudinal ultrasound scan to the right of midline showing a 5 cm cyst in the right ovary with no internal echoes. (b) Axial T2-weighted MRI scan showing a left-sided ovarian cyst (white arrow) with benign features. There is a small volume of free fluid in the pouch of Douglas (black arrows). U, uterus.

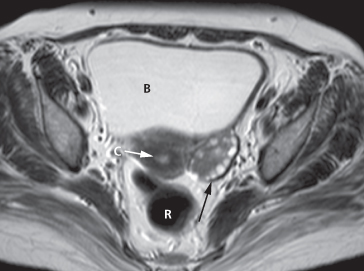

The typical features of polycystic ovaries on ultrasound or MRI include large volume ovaries with multiple small follicles arranged around the periphery, forming the appearance of a ‘string of pearls’ (Fig. 9.8).

Fig. 9.8 Polycystic ovary. Axial T2-weighted MRI demonstrating a left ovary (black arrow) which is large in size and has multiple small cysts arranged around the periphery of the ovary, in a characteristic ‘string of pearls’ distribution. B, bladder; C, cervix; R, rectum.

Ovarian Tumours

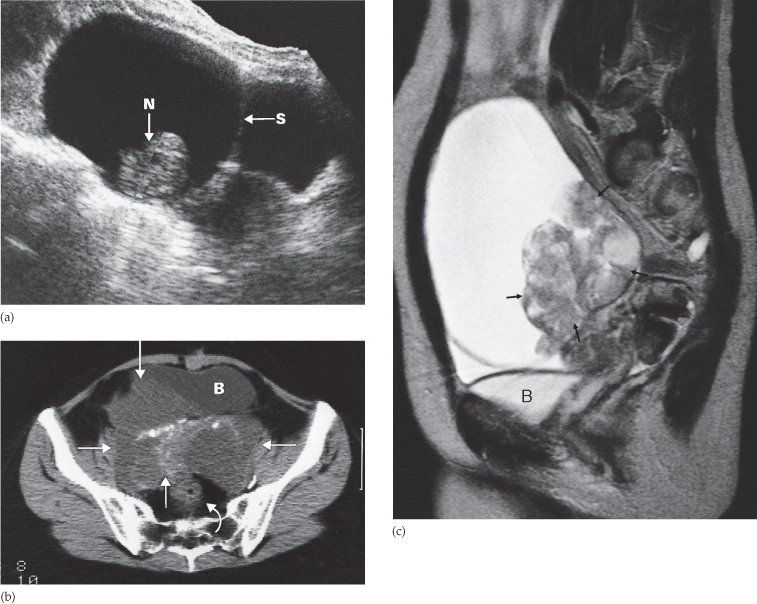

The commonest ovarian tumours are the cystadenoma and the cystadenocarcinoma. Ovarian tumours can be predominantly cystic, solid or a mixture of the two (Fig. 9.9). Those that are cystic may be multilocular. On ultrasound, the recognized features of benign lesions and malignant lesions are listed in Box 9.1. In some cases it is not possible to say whether the mass is benign or malignant based on the ultrasound, unless there is evidence of local invasion or distant spread. MRI may be used to further characterize indeterminate masses as benign or malignant prior to deciding on patient management. With disseminated malignancy, deposits within the omentum and ascites may be visible (see Fig. 10.3), but small omental and peritoneal metastases are frequently difficult to detect. FDG-PET/CT may be used to demonstrate the extent of disseminated disease in order to aid treatment planning (Fig. 9.9d). Ultrasound, CT and MRI may show hydronephrosis from ureteric obstruction by the tumour and may also demonstrate enlarged lymph nodes, liver metastases or pleural effusions.

Fig. 9.9 Ovarian carcinoma. (a) Longitudinal ultrasound scan showing a very large multilocular cystic tumour containing septa (S) and solid nodules (N). The lesion was a cystadenocarcinoma. (b) CT scan showing a large partly cystic, partly solid ovarian carcinoma (arrows). The tumour, which contains irregular areas of calcification, has invaded the right side of the bladder (B). The rectum is indicated by a curved arrow. (c) MRI scan showing a partly solid (arrows) and partly cystic tumour. The cystic component is of high signal intensity on this T2-weighted image. (d) FDG-PET/CT in a patient with disseminated ovarian cancer. Abnormally increased activity is seen in the chest, liver and peritoneum. Normal cardiac (C) and bladder (B) activity is demonstrated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree