© Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014

Marc Lemmerling and Bert De Foer (eds.)Temporal Bone ImagingMedical Radiology10.1007/174_2014_970Indications for Temporal Bone Imaging: The Clinician’s Approach

(1)

European Institute for ORL, Sint-Augustinus Hospital, Wilrijk, Belgium

3.1 Let Us Now See Which Elements of the Diagnostic Work-up Should Urge the Clinician to Ask for Imaging

Abstract

Recent progress in imaging technology has greatly improved the diagnostic quality and the therapeutic safety in the field of otology and neurotology. This makes imaging one of the cornerstones in the diagnostic work-up and follow-up of temporal bone pathology. By confirming the clinically and audiometrically suspected diagnosis, imaging helps to select the best and safest diagnostic option. It allows the ear surgeon to prepare for surgery in the most efficient way, it identifies contraindications and concomitant ear pathology and warns against potential surgical complications. This allows the clinician to counsel the patient in an honest and a realistic way. The chapter describes how the clinician can decide which imaging sequences to ask for, taking as a starting point the conventional diagnostic aids such as personal and family medical history, symptoms and clinical signs, micro-otoscopy, and audiological work-up. Two pathological situations are described in detail as examples: (1) the patient with conductive or mixed hearing loss with an intact tympanic membrane; (2) the pre-operative work-up and post-operative follow-up of the cholesteatoma patient. A close collaboration between clinician and radiologist is crucial to ensure a correct understanding of the indications for imaging by the clinician, and the selection and application of the correct sequences by the radiologist.

1 Introduction

While imaging since its early days has been an important diagnostic tool in the diagnosis of temporal bone disease, due to the hidden nature and limited accessibility of its structures to the clinician’s unaided or even microscope-aided eye, recent progress in imaging technology has greatly improved the diagnostic quality and the therapeutic safety in the field of otology and neurotology.

The advent of new therapeutic possibilities necessitated improved image resolution and a better discrimination of structures and tissues within the temporal bone.

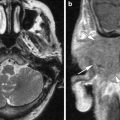

As a consequence, recent MRI sequences open the door to the routine application of imaging in the diagnostic work-up and post-operative follow-up of cholesteatoma, in the latter case even replacing routine exploratory second stage surgery for residual disease. Because of its enhanced resolution and lower radiation dose, Cone beam CT (CBCT) is finding its place in the pre-operative work-up of conductive and mixed hearing loss (HL), facilitating patient counseling and preventing erroneous indications for surgery as well as helping to avoid per-operative complications. The overall effect is a more focussed, safer, more successful and cost-effective intervention.

Within the context of the very variable regional socio-economic conditions throughout the world, otologists and neurotologists need to adapt to these new possibilities, broadening their indications for imaging for the pre-operative work-up and post-operative follow-up. The close collaboration between clinician and otoneuroradiologist is the cornerstone for success, necessitating frequent contacts and discussion of the cases: a real on-going clinico-radiological conversation. The clinician should provide follow-up feedback to his radiologist in order to corroborate or invalidate radiological protocols, thus offering to the radiologist the opportunity of fine-tuning his technique and skills. The radiologist must keep the clinician informed on the development of new imaging sequences and techniques, thus allowing the clinician to identify new clinical applications.

The importance of an intense collaboration between clinician and radiologist cannot be sufficiently emphasised. It is part of a culture of interaction and cross-fertilisation between different specialties.

Therefore, I urge my ENT trainees to take their questions about imaging to their colleagues in the imaging department. Vice versa, young radiologists should ask the clinicians for regular feedback on their imaging protocols and take every opportunity to attend a number of surgical interventions connected to the cases they imaged, in order to familiarise themselves with the work and language of their clinical colleagues.

A common complaint by radiologists is the often very limited clinical information they receive from the clinician. A closer collaboration automatically resolves this important communication flaw, which often leads to either incomplete or superfluous examinations. It is the clinician’s task to amend this.

The various chapters in this book will provide details related to specific pathological entities. This introductory chapter aims to inform the reader on the questions the clinician puts to his radiologist, or in other words, on the kind of information the clinician will expect from his radiological colleagues. As cases in point, two clinical situations will be discussed in some detail: (1) the diagnostic challenge of a conductive or mixed HL with an intact tympanic membrane (TM); (2) the important role of imaging in the pre-operative work-up and post-operative follow up of cholesteatoma cases.

2 Which Information Does the Clinician Need from the Radiologist?

Imaging confirms or contradicts a diagnosis suspected on the basis of the information acquired from: (1) the personal and family history; (2) the clinical examination (otoscopy, vestibular tests); (3) the audiometry and vestibular test battery.

It helps to select the best and safest therapeutic option. If this means surgery, it helps to prepare the operation in the most efficient way: define the urgency of the intervention (e.g., the timing of cholesteatoma surgery in a school attending child); select the best surgical approach; prepare the necessary instruments and surgical aids (e.g., LASER, micro-drill, biological glue, facial nerve monitor, etc.); identify some potential contraindications (e.g., cochleovestibular anomalies in stapedotomy for otosclerosis); identify concomitant pathology of the temporal bone (e.g. vestibular schwannoma in mixed HL); warn the surgeon about potential anatomical risk factors which could lead to per- or post-operative complications (e.g., a dehiscent facial canal with herniation of the facial nerve impacting on the stapes in functional middle ear surgery). This information will allow the surgeon to counsel the patient in an honest and realistic way. As such, pre-operative imaging (or the absence of it) has important medicolegal implications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree