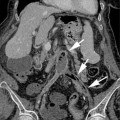

Fig. 12.1

Male, 62 years old, suffering from a gunshot wound to the left flank. a Coronal MPR image demonstrates the bullet entrance hole as a focal defect of the skin at the left flank associated with subcutaneous fat tissue stranding (white arrow). b, c Two noncontiguous axial scans show a hematoma at the mesenteric root (b, arrowhead) and meso-sigma (c, arrowhead) with an active bleeding pooling (c, arrow) along the course of the bullet trajectory. d At the end of its course, the bullet lies between the large and small gluteus muscles

Considering the chest, penetrating traumas are associated with a high incidence of pneumothorax, hemothorax, lung contusions and lacerations and vertebrocostal fractures. When bullets or fragments get in between the vertebral bone structures, there is high risk of spinal cord injury (Fig. 12.2). Documentation of mediastinal vessels or main bronchi lesions is quite rare, since these injuries are mostly incompatible with life.

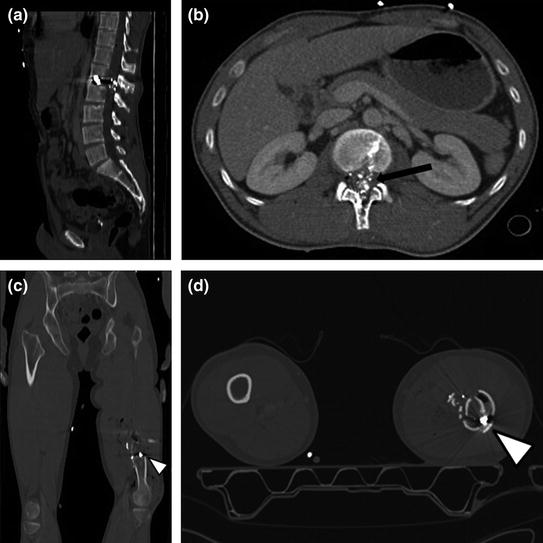

Fig. 12.2

A 28-year-old male victim of shooting with gunshot bullets locked in a lumbar vertebra and in left femur. a Sagittal MPR image shows a bullet locked at the L1–L2 intervertebral disk. b By impacting with the vertebral arch, the bullet has generated small metal and osseous fragments within the spinal canal causing an irreversible medulla damage (b, arrow). c Coronal MPR image and d axial scan show fracture of the femoral diaphysis caused by a further bullet that appears locked in the context of bone fragments (arrowheads)

In abdominal and pelvic regions, recognition of peritoneal injuries is essential for the correct patient’s management. Abdominal violation is evident when a wound is associated with hemorrhage, free air and fluid, fat stranding, bullets or any other fragment in the peritoneal cavity. Intraperitoneal free fluid or air associated or not with solid organ, hollow viscus and/or mesenteric/vascular injuries should be carefully considered because they may also come from extraperitoneal structures [15, 20].

Small and large bowel are the most frequently injured organs as a result of penetrating wounds. Extravasation of contrast medium into the extraluminal space or direct evidence of a discontinuity in the viscera wall, represent the highest specific signs of gastrointestinal transmural injury. These signs usually require an immediate surgical approach.

Parietal hematomas, intra or extraluminal active bleeding (Fig. 12.3), and/or a focal wall thickening of a hollow viscus are also considered highly sensitive signs. The association with a mesenteric injury is not rare, manifesting as fat stranding or thickening, with or without active bleeding. Depending on the clinical context, nonoperative versus surgical or interventional approach with selective embolization should be selectively considered [27, 28].

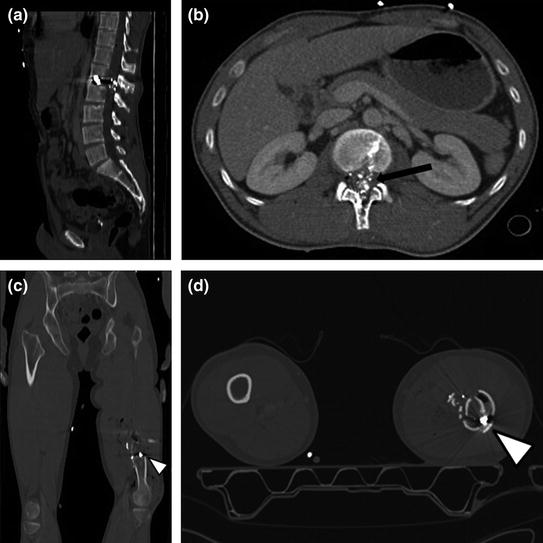

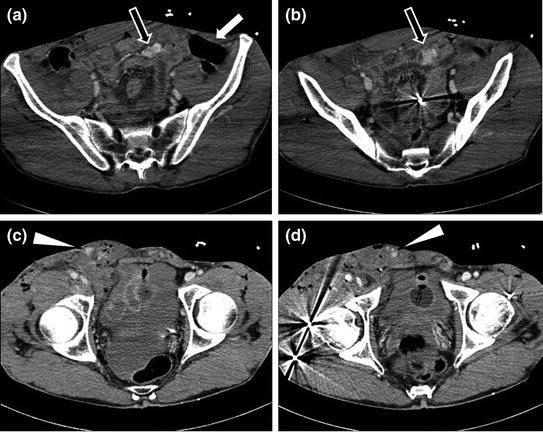

Fig. 12.3

A 42-year-old man with GI and groin injuries and active bleeding after birdshot wounds. a, b Two noncontiguous axial scans show foci of active bleeding in the pelvic cavity (black arrows) associated with an adjacent collection of free air in the left iliac fossa (a, white arrow) due to transmural injury on an ileal loop containing a birdshot bullet (b). c, d At the pelvis, two noncontiguous axial scans demonstrate hematoma of the right inguinal region, with mild subcutaneous emphysema and multiple foci of active bleeding (arrowheads). Furthermore, two birdshot bullets are visible in the contest on the right pelvic muscles (d)

Abdominal solid organs are often involved in penetrating traumas. Splenic injuries are more frequently associated to stab wounds, since majority of people is right-handed. Gunshot wounds in parenchymas are recognizable by the presence of a hypodense band of devascularization due to the transit of the projectile or a “cavity” due to tissue necrosis for the high temperature of the projectile. Sometimes a hollow space in the parenchyma persists over a time. Frequently in the context of parenchyma, vascular lesions such as foci of active bleeding, pseudoaneurysms, and/or arteriovenous fistulas are detectable [20].

In cases of renal injury after penetrating trauma, it is mandatory excluding foci of active bleeding and/or injuries at the excretory system, although very rarely the latter represent a priority in terms of immediate treatment (Fig. 12.4) [29].

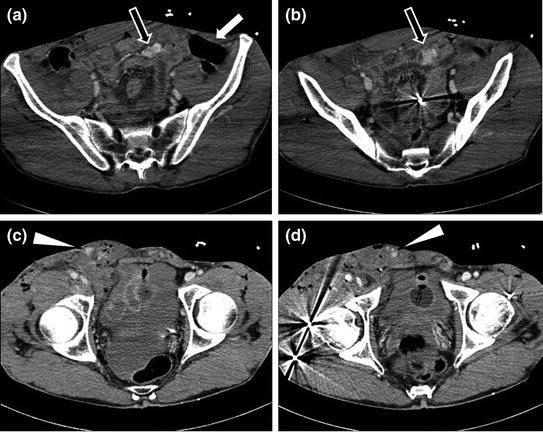

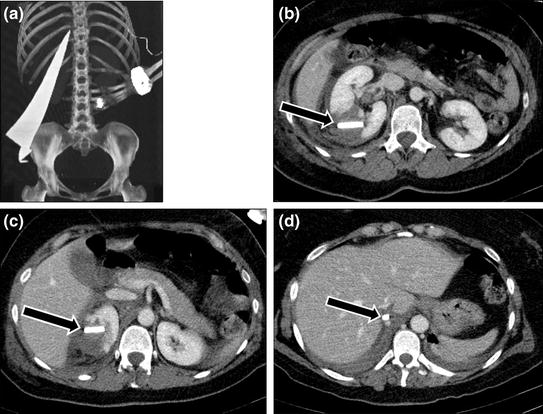

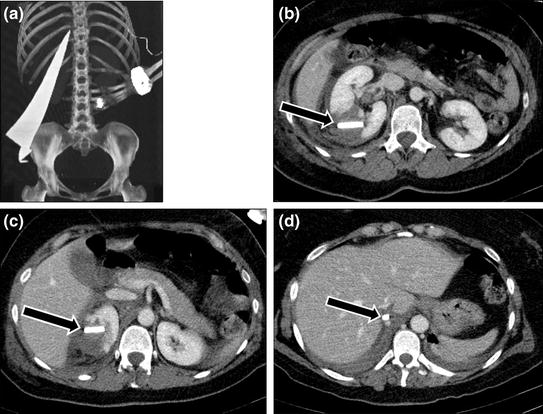

Fig. 12.4

A 35-year-old woman with deep retroperitoneal injury due to a blade of glass after a disastrous accidental fall into a window. a VR reconstruction image shows the presence of a huge glass splinter in the right flank. b, c, d Three noncontiguous axial scans show a deep laceration of the renal parenchyma with perirenal hematoma, due to the presence of a foreign body passing through the body in a caudal-cranial direction (arrows). d Note that the blade glass apex comes in close proximity with the retrohepatic inferior vena cava (arrow). No signs of retroperitoneal vessel laceration are visible. (By courtesy of Dr. G. Casaburo, Department of Radiology, S. Paolo Hospital, Naples, Italy)

In addition, MPR reformations are useful for evaluating the extent of tears, providing an additional viewpoint of any parenchymal injuries (Fig. 12.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree