Fig. 3.1

Lateral plain film shows the presence of a radiopaque foreign body (chicken bone) (arrow) anterior to the body of C7

Esophageal Foreign Bodies

The esophagus is another common site for impaction of FBs that are accidentally or purposefully swallowed. Patients who have esophageal FBs can be loosely classified into four groups: (1) pediatric patients, (2) psychiatric patients and prisoners, (3) patients who have underlying esophageal disease, and (4) edentulous adults. The largest group is the pediatric group, which corresponds to 75–80 % of cases. Most of these children are aged 18–48 months [12]. Anatomic features of the esophagus are important to identify because there are areas that are at risk of FB impaction. The first area is located posterior to the cricoid cartilage, at the level of the C6 vertebra, where the esophagus begins with the upper esophageal “sphincter” or cricopharyngeus muscle. The second is at the level of T4 where the distal aortic arch descends posterior to the midesophagus [5]. Distally, there is also an area of narrowing at the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The LES is the narrowest point of the entire gastrointestinal tract in adults, and it is the location where most FBs become impacted [13]. Many materials can lodge in the esophagus; they can be classified as food bolus impactions or true FBs. True FBs can be subdivided into blunt objects, sharp objects, and miscellaneous (narcotic packs and disk batteries). The most commonly encountered upper esophageal FBs include dental work, coins (Fig. 3.2), bones, and fruit pits. Other frequently encountered objects in children include crayons, marbles, small toys, keys, stones, and safety pins. FBs are common causes of noniatrogenic esophageal injury. Complications from perforation of the hypopharynx and upper esophagus include retropharyngeal abscess [14], mediastinitis, and even rare instances of aortoesophageal fistulas or tracheoesophageal fistula [15, 16], penetration of the common carotid [17] and facial artery [18], thyroid abscess [19], and epidural abscess [20]. The first diagnostic tool for the evaluation of patients with suspected pharyngoesophageal FBs is radiography. Many objects, such as meat, tiny bones, aluminum, glass, plastic, and wood, may be radiolucent and not visualized on plain radiographs [21]. Although some of these objects may be detected when oral contrast is given, there is a limited role for contrast studies in the management of FBs. Barium studies should be avoided if there is clinical evidence of high-grade obstruction or there is suspicion of esophageal perforation, as there is the potential for barium spillage into the mediastinum or pleural space. If barium is used, a minimal amount of a thin solution is preferred, as residual barium in the esophagus obscures visualization during a subsequent endoscopy. Gastrografin may be helpful in localizing a suspected perforation, but because of its hypertonicity, it may cause severe pneumonitis if aspirated [21].

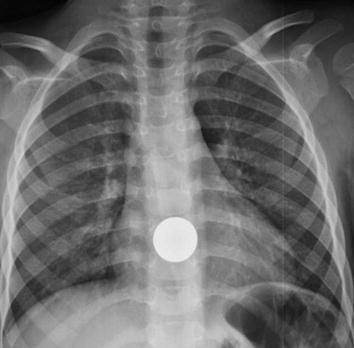

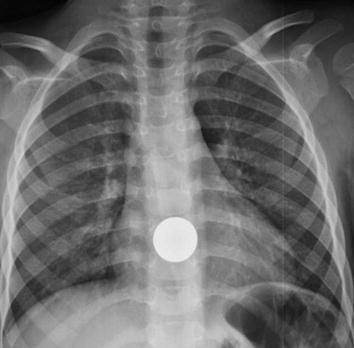

Fig. 3.2

Chest radiograph shows the presence of a radiopaque foreign body (coin) lodged at the level of the distal portion of the thoracic esophagus

Stomach and Duodenal Foreign Bodies

The vast majority of FBs that enter the stomach pass through the entire GI tract uneventfully. Objects longer than 5 cm may have difficulty negotiating the tight curve of the duodenum, and objects larger than 2 cm in diameter may have difficulty passing the pylorus or ileocecal valve [22, 23]. Less than 1 % of FBs that enter the stomach cause perforation of the bowel [24].

Battery ingestions (Fig. 3.3) are common among children, impaired individuals, and those with psychiatric disorders. There are four types of button batteries that range in size from 6 to 23 cm: manganese dioxide, silver oxide, mercuric oxide, and lithium manganese. The larger the diameter of the battery, the more likely it is to lodge in the esophagus. The possible mechanisms of injury from battery ingestion include leakage of battery contents, electrical discharge, and pressure necrosis. Another potential mechanism of injury is absorption of heavy metals from broken or fragmented batteries. However, no cases of heavy metal poisoning from disc battery ingestion have been reported. The alkaline solutions in these batteries can cause liquefaction necrosis and saponification in the mucosal surface of the GI tract. If the battery remains in place, ulceration and perforation can occur.

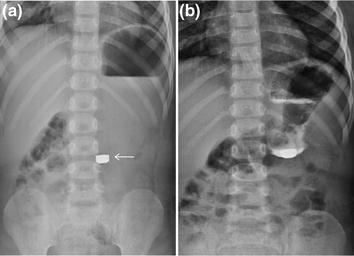

Fig. 3.3

Plain abdominal film shows an ingested radiopaque foreign body (battery) (a, arrow). The exact location of the ingested foreign body is confirmed after oral administration of gastrografin (b)

Foreign Bodies of the Small and Large Intestine

Once in the small intestine, the most common impaction point is the ileocecal valve, followed by the hepatic and splenic flexures. Less than 1 % of ingested foreign bodies cause perforation of the gastrointestinal tract. Sharp, elongated objects (Fig. 3.4) are the most likely to penetrate the bowel mucosal lining and cause significant injury to the bowel wall or frank perforation [1].

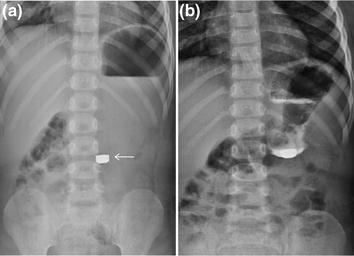

Fig. 3.4

Plain abdominal film shows an ingested radiopaque foreign body (nail) (arrow) located at the level of the distal portion of the descending colon

Two interesting phenomena occur that help protect the bowel wall from injury during foreign body passage. The first is related to axial flow and a tendency for sharp objects to be turned in the intestine so that the sharper end will trail down the lumen. Second, once the foreign object reaches the colon, it becomes surrounded by fecal material that aid in bowel wall protection.

Management of sharp FBs in the intestine includes daily radiographs to document progression of the FB. If there is no distal progression over a 3-day period or if the patient becomes symptomatic, emergent surgical consultation should be obtained [25].

MDCT is regarded to be a good modality for detecting and characterizing FBs in the GI tract and for evaluating the risk of complications. However, metallic FBs produce beam-hardening artifacts, which can obscure their contours and those of surrounding structures. Although scout MDCT images can be helpful for identifying FBs, they have lower resolution than plain radiographs. The majority of FB ingestion patients essentially need close observation and monitoring by serial plain radiography. Furthermore, because MDCT has a greater radiation hazard than plain radiography, plain radiography is the better alternative for follow-up examinations particularly in the paediatric population.

Rectal Foreign Bodies

The number of patients presenting with retained rectal foreign bodies appears to have increased in recent decades. Foreign objects retained in the rectum may result from ingestion or direct introduction through the anus (more common). Affected individuals often will make unsuccessful attempts to remove the object themselves, resulting in further delay of medical care and potentially increasing the risk of complications. As with upper GI foreign bodies, the types of objects introduced through the anus are unlimited. Objects such as vibrators, rubber phallus, vegetables (carrots, zucchini, corn cob) (Fig. 3.5), fruit (apple, banana), stones, wire, toothbrush, screwdrivers, rodents, cans, bottles, and jars are but a few of the retained rectal objects reported. Autoeroticism has been reported as the most common reason for anally inserted foreign bodies [26]. Diagnostic problems can occur with trans-anal rectal injuries, because of the natural hesitancy of the patient to describe what might have been a very embarrassing and socially unacceptable incident. Trans-anal high hydrostatic pressure may cause severe colorectal injury, necessitating resection of the blown injured segment. The firm lateral support of the rectum makes the rectosigmoid junction the first part to be hit by the pressure column, which acts as a solid body as it opens the anal sphincter [3].

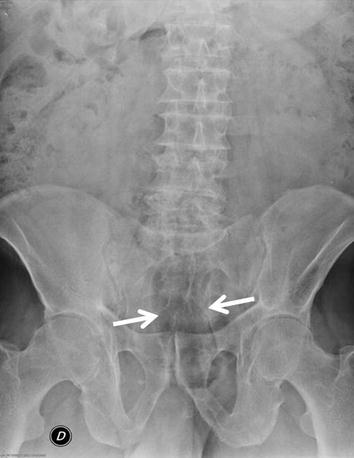

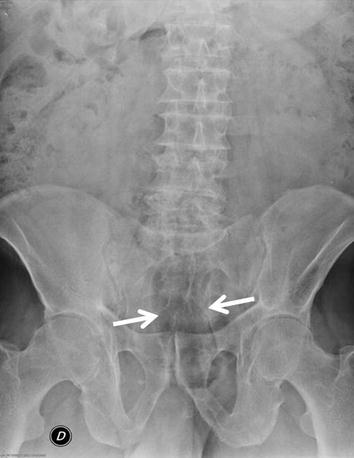

Fig. 3.5

Plain abdominal film shows a radiolucent foreign body (vegetable) (arrows) located at the level of the rectum

Body Packing

Over the last two decades, drug smuggling has not only increased worldwide, but the gastrointestinal tract has been also used more frequently as a vehicle for smuggling narcotics [27, 28]. Body packing and body stuffing are the terms employed for intracorporeal concealment of illicit drugs, mainly cocaine and heroine. The general characteristics of a body packer include: (1) returning from a trip abroad in a location with a history of illicit drug exporting; (2) history of frequent trips; (3) high profit drugs such as cocaine or heroin involved; and (4) the packaging material is made of high-grade latex, aluminum foil, or condoms. In addition to transporting cocaine and heroin, body packers may smuggle amphetamines, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”), marijuana, or hashish. Occasionally, they ingest more than one type of drug. Body packers usually carry about 1 kg of drug, divided into 50–100 packets of 8–10 g each, although persons carrying more than 200 packets have been described [28]. Patients suspected of being body packers require radiographic evaluation. Plain abdominal X-ray is the most widely used radiological tool to detect drug-filled packets of 2–8 cm within the gastrointestinal tract of body packers [27, 29, 30]. However, due to limited contrast resolution, conventional radiographs (CR) of body packers reveal the presence of drug containers in 40–90 % of cases only [27, 28, 31–33]. Several specific signs on the abdominal radiograph may suggest the presence of body packing: multiple radiodense foreign bodies, a “rosette-like finding” formed by air trapped in the knot where a condom is tied [27, 32] and a “double-condom” sign [27, 31] in which air trapped between layers of latex makes them more visible. The last finding may also suggest a loss of integrity of the packing material [34]. Abdominal ultrasound (US) [27] and radiographic studies after oral intestinal opacification with hydrosoluble contrast agents have been used and recommended for investigation of body packers. However, for detection of the small-sized cocaine-filled packets, which may be located anywhere in the digestive tract, none of these two methods is considered very sensitive [30].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree