Overview

Location

• The gallbladder (GB) and biliary tract are intraperitoneal structures (enclosed in the sac formed by the parietal peritoneum).

• The gallbladder is located in the fossa on the posteroinferior portion of the right lobe of the liver. The gallbladder fossa is closely related to the main lobar fissure (MLF) of the liver, one of the normal folds throughout the liver that typically form the spaces that contain various blood vessels or ligaments. The MLF runs obliquely between the neck of the gallbladder and right portal vein. It contains the middle hepatic vein and separates the right and left hepatic lobes. Its course is short and variable.

• The gallbladder is extremely variable in position and location as a portion of it is attached by long mesentery, allowing for movement. The neck or narrow portion of the gallbladder, however, is fixed in its position at the main lobar fissure.

• The biliary tract or “tree” runs between the liver and the duodenum.

Anatomy

• The right and left intrahepatic ducts exit the liver at the porta hepatis (area of the hilus/opening where the portal vein and hepatic artery enter the liver and the common duct exits) and meet to form the common duct. The superior or proximal portion of the common duct is referred to as the common hepatic duct (CHD). The CHD runs slightly inferomedially where it is joined by the cystic duct (directs bile from the CHD into the neck of the gallbladder) to form the distal portion of the common duct, the common bile duct (CBD). The CBD courses inferior and medial, all the way to the duodenum.

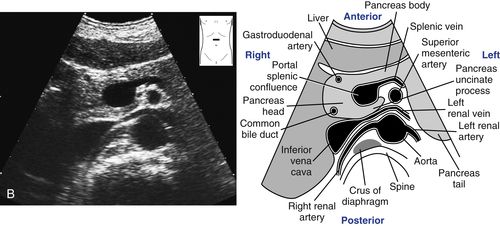

• As the CBD courses inferomedially, it is referred to as the retroduodenal CBD, as it passes behind the first part of the duodenum en route to the head of the pancreas. At the head of the pancreas the CBD either passes through the pancreatic head or runs along a groove on the posterior surface of the head to meet with the main pancreatic duct (or duct of Wirsung, which transports and discharges pancreatic enzymes into the duodenum). Joined together or separately, the CBD and duct of Wirsung course slightly to the right to enter the second portion of the duodenum at the ampulla of Vater, a dilatation of the duodenum, where they empty bile and pancreatic juices to aid the digestive process.

• Normal common duct size is variable according to the amount of bile it contains and patient age. The common duct is known to enlarge with age. CHD is considered normal in size up to 4 mm; the CBD up to 6 mm. Following loss of GB function (as a result of cholecystectomy or gallbladder disease), the common duct assumes bile storage function and is considered normal in size up to 10 mm.

• The gallbladder is a muscular, membranous sac that has been described as pear-shaped, conical, or like a partially filled water balloon. Its narrow end is called the neck, a tube-like structure that joins the cystic duct. Its rounded “bottom” is called the fundus. The portion between the neck and fundus is called the body.

• The gallbladder serves as a storage site for bile; it is not essential to life. Without the gallbladder, the biliary tract (ducts) continues to transport bile from the liver to the duodenum.

• The size of the gallbladder is variable according to the amount of bile it is storing. It is considered normal up to 3 cm wide and 7 cm to 10 cm long. In a fasting patient, the gallbladder wall measurement is considered normal up to 3 mm.

Physiology

• The gallbladder and biliary tract are considered accessories to the digestive system because they store and transport the bile that is manufactured in the liver to the duodenum to help digest fat.

• The hepatic and biliary ducts passively transport bile directly to the second portion of the duodenum or by way of the gallbladder where bile is stored and concentrated.

Sonographic Appearance

• Since the position of the gallbladder is variable depending on the amount of bile it contains and/or the length of its mesenteric attachment its orientation in the body is also variable. Therefore, the gallbladder long axis can be visualized in any scanning plane.

• As demonstrated in the images below, A, the normal bile-filled gallbladder appears longitudinally as an anechoic, oblong structure with bright, thin walls and B, axial sections appear as anechoic, round or oval structures with bright, thin walls.

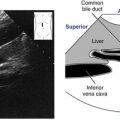

• The following images show how A, the bile-filled common duct appears longitudinally as an anechoic tubular structure with bright, thin walls and B, axial sections of the duct appear as small, anechoic, round structures with bright, thin walls.

• When there is a question of dilated bile ducts, it is important to make a distinction between the structures that comprise the portal triad: the proper hepatic artery, common duct, and portal vein at the level of the porta hepatis. The following oblique, transverse scanning plane image shows that at the level of the porta hepatis, the portal vein (1) lies posterior to the proper hepatic artery (2), which is on the left and the CBD (3), located on the right. The appearance of the axial sections of the portal triad is often referred to as “Mickey’s sign” as they resemble a face and two ears.

Normal Variants

Gallbladder

• Shape variations:

• Segmental contractions: These “segments” disappear when the patient changes position or fasts.

• Phrygian cap: The fundus is folded over giving the gallbladder a “capped” appearance.

• Position variations:

• The position and location of the gallbladder is variable because it is suspended by long mesentery.

• Very rare, deep fossa, intrahepatic gallbladder.

• Septations:

• May partially or totally divide the gallbladder.

Biliary Tract

• Duplications:

• Although very rare, the common duct may be partially or completely duplicated.

• Level variations:

• The level of the junction of the cystic duct and common hepatic ducts is variable.

• Septations:

• May partially or totally divide the cystic duct, producing various degrees of double gallbladder.

Preparation

Patient Prep

• The patient should fast for 8 to 12 hours before the study. This ensures normal gallbladder and biliary tract dilatation and reduces the amount of bowel gas.

• If the patient has eaten within 4 to 6 hours, still attempt the examination.

Transducer

• 3.0 MHz or 3.5 MHz.

• 5.0 MHz for thin patients.

Breathing Technique

• Deep, held inspiration.

Patient Position

• The gallbladder and biliary tract study is performed with the patient in two different positions.

• Supine and left lateral decubitus.

• Left posterior oblique, sitting semierect to erect or prone as needed.

Gallbladder and Biliary Tract Survey Steps

Gallbladder • Longitudinal Survey

Sagittal Plane • Transabdominal Anterior Approach • First Patient Position

First Patient Position: Supine

1. Begin scanning with the transducer perpendicular, just inferior to the costal margin at the right medial angle of the ribs. Have the patient take in a deep breath and hold it. In most cases, the portal vein and gallbladder neck should come into view. If the gallbladder is not visualized here, locate the bright main lobar fissure of the liver that extends from the right branch of the portal vein to the gallbladder neck.

2. Once the gallbladder is identified, find its long axis. This can be accomplished by slightly twisting/rotating the transducer first one way, then the other, to oblique the scanning plane according to the lie of the gallbladder. Occasionally, no oblique is necessary.