and Siddharth P. Jadhav2

(1)

Department of Radiology, University of Texas Medical Branch Pediatric Radiology, Galveston, TX, USA

(2)

The Edward B. Singleton Department of Pediatric Radiology, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA

Abstract

This chapter deals with general considerations for obtaining adequate radiographs. Included are “which views to obtain” and the value of comparative views. Soft tissues and joint fluid are emphasized as they often aid in directing one to the bony injury. The role of MR is briefly cited.

What Views Should Be Obtained?

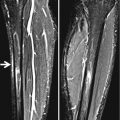

For the extremities, at least two views, usually at right angles to each other, are necessary and most often consist of frontal and lateral projections of the involved extremity. In addition, in some cases, for example, the wrist, ankle, hand, and the foot, a third oblique view is fairly well standard. In the shoulder, internal and external rotation views are obtained, while in the hip, AP and frog-leg views are standard. In addition, it is of considerable benefit to obtain comparative views of the other (normal) side. They are very useful for the detection of subtle findings and fractures [1–5].

Over the years, there has been some movement towards discouraging the routine use of comparative views, but in this regard, in a summary on the subject in a report by the Committee on Radiology of the American Academy of Pediatrics, so many loopholes in the premise that comparative views are not required were identified that the loopholes virtually destroyed the original premise. To this end, and quoting directly from their report [6], the following is presented.

“Injury to the hip joint” is a notable exception to the selective approach; at least one view should routinely include the normal hip, with the gonads shielded. Hip injuries in children are most frequently associated with joint effusion, which can be detected only with comparing similar measurements of the opposite joint space.

Other specific areas of the appendicular skeleton may require more comparative views. The elbow, with a relatively large number of ossification centers appearing at widely varying times, may prove confusing even to the experienced radiologist; comparison view of this joint may be requested frequently. Detection of joint effusion in the knee and ankle may necessitate a comparison view, in at least one projection. Comparison views may also be helpful in evaluating the tissue planes and subcutaneous fat in suspected inflammatory conditions of the soft tissues or “bones.”

Finally, a conclusion from the same communication suggests that no one uniform policy can be expected for all individuals dealing with pediatric trauma: “A number of theoretical and practical considerations will continue to determine the use of comparison views. Personal conviction based on experience and training is the major theoretical consideration. Practical considerations include the availability of radiologic consultation, the expertise of the physician who initially interprets the study, and clinical demands. An individual’s policy toward the use of comparison images is a balance of these considerations.” This latter sentence is probably the most important in this ongoing controversy. Do what you have to do, but be sure in your mind that you will not miss any fractures when you obtain views of the injured side only. One might ask, “How sure am I that I am not missing a bending fracture, a subtle Salter–Harris type I injury, or a minimal buckle fracture?”

Now, what about cost and radiation exposure encumbered with the use of comparative views? In our study [1], it was demonstrated that the cost of obtaining hardcopy comparative views was negligible and so was the risk of radiation injury to the patient. Indeed, it is difficult to construct a case against comparative views if one wants to be able to detect subtle injuries. This is especially true if one does not look at pediatric images on a full–time basis. How did I (LES) come to use comparative views? A number of decades ago, I was placed in charge of pediatric radiology in a teaching hospital. One of the first things that came to my attention was that I was calling kids back for repeat X-rays or X-rays of the other extremity to decide whether a fracture was present. This seemed to be redundant and inconvenient and indeed, not necessary. So I decided that comparative views should be obtained during the first imaging encounter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree