11 Genitourinary Disease Normal menstruation is characterized by bleeding that occurs for fewer than or equal to 8 days, once every 24 to 38 days, and a volume that does not significantly interfere with quality of life. Any type of bleeding outside these parameters is considered abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). Generally speaking, premenopausal abnormal uterine bleeding is less concerning than postmenopausal. AUB in a postmenopausal patient can be an indicator of an endometrial malignancy. Some patients with uterine leiomyomas, more commonly known as fibroids, may come to IR as self-referrals, so it’s important to have a basic understanding of the work-up for AUB, and have comfort in accurately diagnosing fibroids. A good gynecologic and obstetrical history includes the patient’s pattern of menstrual cycles, vaginal bleeding outside of normal menstruation, past pregnancies, and history of infertility. Bimanual and speculum exams can be deferred if the patient has had a recent gynecological visit (< 1 month). The differential when considering abnormal uterine bleeding in a premenopausal patient includes endometrial polyps and adenomyosis (▸Table 11.1). Endometrial polyps are focal outgrowths of glandular tissue and blood vessels into the uterine cavity, typically appearing as a beefy red, friable mass. Adenomyosis is abnormal proliferation of endometrial tissue within the myometrium, characteristically resulting in a large, boggy uterus and dysmenorrhea. The diagnosis of fibroids is based on the clinical history and confirmatory imaging. Symptomatic patients most commonly present with complaints of heavy menstrual bleeding. The disruption of the endometrial surface and myometrium by these benign smooth muscle tumors contributes to menorrhagia. You may have to specifically ask about “bulk symptoms” caused by mass effect on adjacent organs, including constipation, urinary frequency, flank pain, or pelvic pain. A focused exam includes evaluation for pelvic masses, cervical lesions, and cervical tenderness. The clinical history may be strongly suggestive for fibroids, but a pelvic ultrasound is typically necessary to confirm the diagnosis. If the uterus is quite large, there are atypical appearing fibroids on ultrasound, or if further information is needed for treatment planning, MRI is usually the next step (▸Fig. 11.1). MRI also has the benefit of being able to distinguish adenomyosis from fibroids. CT is sensitive for the incidental detection of fibroids but is not typically a modality used specifically for this work-up. Table 11.1 Causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the premenopausal patient

11.1 Uterine Fibroids

Work-up for Fibroids

Pathology | Description | Defining features |

Fibroids | Benign smooth muscle tumor | Heavy menstrual bleeding, irregularly shaped uterus |

Adenomyosis | Endometrial tissue in uterine muscle layer | Heavy menstrual bleeding, dysmenorrhea, large, boggy uterus on exam |

Endometrial polyps | Outgrowth of endometrium into uterine cavity | Heavy menstrual bleeding |

Fig. 11.1 Sagittal T2-weighted MR image of a well-circumscribed intramural fibroid in the posterior wall of the uterus. (Source: Varicoceles. In: Bakal C, Silberzweig J, Cynamon J, et al, eds. Vascular and Interventional Radiology. Principles and Practice. 1st Edition. Thieme; 2000.)

Fig. 11.2 Diagram depicting fibroids by location. (Source: Imaging Signs. In: Hamm B, Asbach P, Beyersdorff D, et al, eds. Direct Diagnosis in Radiology. Urogenital Imaging. 1st Edition. Thieme; 2008.)

Fibroids are characterized by their location within the uterus: submucosal, intramural, subserosal, and pedunculated subserosal (▸Fig. 11.2).

The majority of patients with fibroids do not need a tissue confirmation prior to treatment. A combination of clinical factors and ultrasound findings should raise suspicion for malignancy in the minority of patients that require a biopsy beforehand. This includes any postmenopausal women with uterine bleeding or a thick uterine stripe.

Management of Fibroids

Fibroids are benign, so no treatment is necessary for asymptomatic patients. For symptomatic patients, a number of medications are available as first-line therapy. Oral contraceptives or hormonal intrauterine devices can help regulate menstruation and alleviate dysmenorrhea, but they don’t actually decrease the size of fibroids, and therefore have no effect on the bulk symptoms. Antiestrogenic medications can shrink fibroids but are associated with a number of side effects. For this reason, they are usually reserved for short-term preintervention purposes, as we’ll discuss below. Menopause itself can reduce the size of fibroids due to a decrease in estrogenic stimuli, so perimenopausal women with bulk symptoms may prefer to wait rather than pursue intervention.

Second-line treatments include surgery (hysterectomy or myomectomy) and uterine artery embolization. Hysterectomy is a definitive therapy for fibroids. The surgery also benefits patients with other uterine pathology (endometriosis, adenomyosis, hyperplasia, or malignancy). Myomectomy is a more conservative surgical option performed hysteroscopically or laparoscopically, and involves focal resection of the fibroids. Myomectomy is limited to fibroids within the uterine cavity or on the serosal surface. Fertility is often preserved when small fibroids are treated with myomectomy. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues (leuprolide) are given as presurgical treatment for 3 to 6 months. This causes hypoestrogenism, resulting in uterine volume reduction and amenorrhea.

Uterine fibroid embolization (UFE), also known as uterine artery embolization (UAE), is an endovascular therapy performed by IR that takes advantage of the rich blood supply of fibroids (Procedure Box 11.1). GnRH analogues are not used prior to UFE like they are for surgery; the resultant decrease in uterine artery caliber and blood flow caused by the medication make endovascular access to the uterine vessels more challenging.

Postprocedure care after a UFE is relatively straightforward. Patients are admitted for up to 24 hours following the procedure, primarily for pain control. Pelvic cramping can be moderate to severe in the first 12 to 24 hours, and typically improves after about a week with NSAIDs. Postembolization syndrome can be seen in up to 40% of patients, and is characterized by low-grade fever, anorexia, nausea, and malaise. Symptoms can be treated with analgesics, anti-inflammatory medications, and oral or intravenous hydration as needed. UFE patients should ideally be followed in clinic roughly 2 weeks and again 3 months after the procedure, with follow-up MRI at 6 months to assess treatment response.

Choosing between Uterine Fibroid Embolization and Surgery

Deciding between hysterectomy and UFE is difficult, but ultimately boils down to the patient’s goals (▸Table 11.2). Do they want a definitive procedure? Do they have a desire for future pregnancy? Are they specifically interested in minimally invasive treatment?

While most studies on UFE have excluded submucosal, subserosal, and pedunculated fibroids, their treatment with UFE is not necessarily contraindicated. Some believed these types of fibroids should not be treated due to potential complications (in particular, the risk of sloughing of the necrotic fibroid into the abdomen or uterine cavity). In reality, there haven’t been any significant reports to support this. Treatment of these other types of fibroids with UFE has been shown to yield similar outcomes to intramural fibroids, and many IRs no longer consider this a contraindication. On the other hand, some types of fibroids, such as pedunculated intrauterine fibroids, are more easily treated with hysteroscopic myomectomy, and there’s no question the surgical approach is better.

Similarly, the total fibroid burden is not an absolute contraindication for a UFE. However, treating very large fibroids with UFE may be inappropriate. Most IRs have an anecdote or two about treatment failure, infection, or serious complication after treating very large fibroids. The upper limit of size that can be treated with UFE probably has more to do with practitioner comfortability than an arbitrary cutoff.

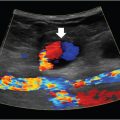

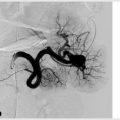

Uterine artery embolization is a minimally invasive treatment for uterine fibroids and may also be required in cases of abnormal placental implantation or for the treatment of refractory postpartum hemorrhage. Arterial access is obtained via the common femoral or left radial artery, and a pelvic arteriogram is performed to delineate anatomy. The anterior division of internal iliac artery is selected with a catheter and another angiogram is performed to identify the uterine artery, which is commonly hypertrophied in patients requiring this procedure. It appears long, tortuous, and anteromedial in location.

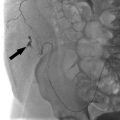

These features help to differentiate the uterine artery from other nearby vessels, including the straighter pudendal artery and the shorter/smaller-caliber cystic artery. It is critical to identify the cervicovaginal branches of the uterine artery, which supply nerve fibers to the cervix and vagina (embolization of which can precipitate cervical or vaginal necrosis, decreased sexual sensation, or inorgasmia). A microcatheter is advanced into the uterine artery distal to the cervicovaginal branches. Embolization is then performed by slowly injecting microsphere particles mixed with contrast under continuous fluoroscopic visualization. The typical particle size is 500 to 700 µm. This size decreases the risk of ovarian shunting, and has been demonstrated to cause less postembolization pain with similar efficacy when compared to smaller particles.

Embolization is repeated on the contralateral side, or alternatively both sides can be treated simultaneously in two-operator settings. The ovarian arteries may occasionally supply some or all of the patient’s fibroids; this is typically suspected due to features on preprocedural imaging or in the setting of a nonhypertrophied uterine artery on iliac arteriography. The ovarian arteries can potentially be selected and distally embolized in some patients, however, the risk of ovarian failure is obviously higher for this technique. Some interventionalists always perform aortography to exclude a significant uterine supply from the ovarian arteries, while others only do this if there is suspicion for incomplete embolization from the uterine arteries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree