7 Oncology It has become abundantly clear that the care of cancer patients is best approached by a multidisciplinary team, including interventional radiologists and medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists. Tumor boards provide an opportunity for experts to collaboratively discuss individualized care for each patient. As the role of interventional onco logy (IO) continues to expand, it is vitally important that every interventional radiologist has the relevant clinical knowledge to understand the complexities of cancer treatment, beyond just the technical aspects of the procedure. This chapter is an introduction to the clinical care of cancer patients who benefit from IO procedures, some of which have been firmly established and others which are newly emerging. Patients with liver lesions are usually referred to a specialist after a lesion has been detected on imaging. Before the patient even walks into the clinic, there is already a good sense of what you’re dealing with based on imaging characteristics (▸Table 7.1). In some cases, the imaging is suboptimal, and further studies are needed. Ultrasound, CT, and MRI all have a role in liver imaging, each with its advantages and disadvantages (▸Table 7.2). Liver lesions are often asymptomatic, and diagnosis may be solely based on imaging. A thorough history and examination is mandatory for all potential IO patients, regardless of the presumed diagnosis. Risk factors can help narrow the differential, especially if imaging characteristics are ambiguous. For example, a young female on birth control is more likely to develop an adenoma, while a patient with cirrhosis should make you think about hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The physical examination should look for cirrhotic stigmata (jaundice, scleral icterus, etc.), signs of extrahepatic malignancy, and an assessment of functional status. Baseline labs should include complete blood count (CBC), liver function tests (LFTs), coags, hepatitis panel, and tumor markers. Table 7.1 Characteristic imaging appearance of liver lesions

7.1 Hepatocellular Carcinoma Approach to a New Liver Mass

Liver lesion differential | Imaging characteristics |

Adenoma | Imaging varies significantly, most commonly arterial hyperenhancement with enhancement equal to normal liver in later phases |

Focal nodular hyperplasia | Arterial hyperenhancement with enhancement equal to liver on later phases, nonenhancing central scar is the key diagnostic feature |

Hemangioma | Discontinuous, progressive, peripheral nodular enhancement |

HCC | Arterial hyperenhancement with washout (decreased contrast relative to normal liver) in later phases; often with a capsule |

Cholangiocarcinoma | Delayed, progressive, persistent enhancement |

Metastatic lesions | Highly variable, often demonstrates peripheral enhancement or arterial hyperenhancement. Usually multiple in number |

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma. | |

Working up a Suspected Liver Malignancy

The first step when working up a suspected liver neoplasm is determining if the patient has cirrhosis. For those with cirrhosis, the diagnosis will almost always be HCC (▸Fig. 7.1). In these patients, the diagnosis can be made with imaging alone.

In a noncirrhotic liver, a malignant-appearing lesion is more likely to be metastatic disease. These patients should undergo a thorough work-up including age-appropriate screening, as well as dedicated CT imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Further evaluation might include MRI (especially if the liver lesion is indeterminate on CT), or percutaneous biopsy (Procedure Box 7.1).

Tumor markers can be helpful, but not always. If they’re elevated, it adds to your evidence, but negative markers do not rule out a malignancy. If HCC is the presumed diagnosis, a baseline alpha fetoprotein (AFP) should be measured. AFP, CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) are mainly used to monitor treatment response to HCC, cholangiocarcinoma, and colorectal cancer, respectively.

Table 7.2 Differences in liver imaging modalities

Modality | Advantages | Disadvantages |

CT | Comprehensive look at abdominal anatomy; fast | Radiation; requires contrast; poor evaluation of the biliary system |

MRI | Better characterization of the biliary system; most sensitive for lesion detection and characterization | Motion limits evaluation of the bowel; takes longer to do; most expensive |

Ultrasound (US) | Quick, portable, cheap; good for screening | Limited ability to detect lesions; poor lesion characterization |

Fig. 7.1 Contrast-enhanced CT showing numerous liver masses with the characteristic appearance of hepatocellular carcinoma. (Source: Herzog C. Diffuse hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In: Burgener F, Zaunbauer W, Meyers S, et al., eds. Differential Diagnosis in Computed Tomography. 2nd edition. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2011.)

The Child–Pugh score was originally intended to predict operative mortality but is now a prognostic indicator for determining the severity of liver disease and the need for transplant in cirrhotics. The score is based on the patient’s total bilirubin, serum albumin, prothrombin time (PT)/international normalized ratio (INR), degree of ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy (▸Table 7.3).

MELD takes into account serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, PT/INR, and serum sodium in some cases. Calculators for the MELD score are available online, with numerical scores corresponding to a 3-month mortality rate (▸Table 7.4).

Biopsies can be performed with either ultrasound or CT guidance. There are several key steps to keep in mind when performing biopsies. First, ensure the target lesion is safely accessible before starting. If the lesion is too deep for the available needles or if there are vital structures between the skin and target, biopsy should not be performed. Next, keep in in mind where the lesion is and be prepared for the organ-specific complications that can arise postbiopsy. Biopsies may seem simple, but serious complications can and do occur.

Fine-needle biopsies use 20- to 25-gauge needles, which are relatively atraumatic and can even go through bowel without causing problems in most cases; however, they may not provide tissue samples large enough for accurate diagnosis. Core biopsy needles are typically 14 to 20 gauge, and can provide more substantial samples. Core biopsies are ideal when the patient has a lesion without a known primary malignancy, and a larger chunk of tissue is needed for diagnosis. These needles generally should not go through bowel.

For liver biopsies, it is important to determine whether the patient has ascites and/or advanced cirrhosis, which can make puncture of the liver capsule difficult and increase the risk of bleeding. Hepatic dome tumors may require a transpleural approach. Superficial lesions should not be approached directly, but instead using a path that allows the needle to traverse some parenchyma before hitting the target lesion. This way, if bleeding occurs, there is a greater likelihood the needle tract will thrombose and result in hemostasis.

Management of HCC

HCC treatment options include resection, transplantation, chemoembolization, radioembolization, ablation, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), and systemic chemotherapy (▸Fig. 7.2).

MELD score | 3-month mortality |

> 40 | 71% |

30–39 | 53% |

20–29 | 20% |

10–19 | 6% |

< 9 | 2% |

Abbreviation: MELD, model for end-stage liver disease. | |

Fig. 7.2 Simplified algorithm for management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Locoregional therapy includes transarterial radioembolization/chemoembolization and percutaneous ablation.

Resection

For nontransplant candidates with HCC, surgical resection is the preferred option, since it has the highest potential to be curative. To determine the resectability of HCC, a number of anatomic and functional factors need to be considered.

Patients with Child–Pugh A cirrhosis may tolerate even a major liver resection so long as they do not have portal hypertension. Patients with Child–Pugh B cirrhosis and no portal hypertension may tolerate a moderate or minor hepatectomy (particularly laparoscopic operations). Major hepatectomy is usually contraindicated. Patients with Child–Pugh C cirrhosis and any patient with portal hypertension are generally not candidates for any liver resection.

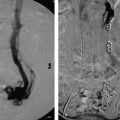

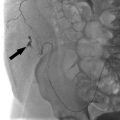

In a noncirrhotic with HCC, up to 80% of the liver can be removed without compromising long-term liver function. In cirrhotic patients with HCC, no more than 50 to 60% of the liver volume can be resected. Interventional radiologists can help these patients by performing a preoperative portal vein embolization (Procedure Box 7.2). Embolization of the portal vein supplying the liver segments to be resected is performed weeks to months in advance of the surgery. The liver responds by hypertrophy of the nonembolized liver segments. As a result, the liver remnant may become large enough to allow for safe resection of the cancer-containing segments (▸Fig. 7.3).

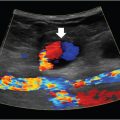

Portal vein embolization is performed to cause hypertrophy of the future liver remnant prior to partial hepatectomy. A needle is used to percutaneously access the portal system (▸Fig. 7.4). Most commonly, the procedure targets the right hepatic lobe; if the left lobe is diseased and planned for resection, the right lobe is usually already large enough to maintain adequate function. Whereas, if the right lobe is diseased, the smaller left lobe may need to hypertrophy beforehand.

Once the portal vein is accessed percutaneously, a catheter is used to select the branch of the portal vein feeding the lobe to be resected, and embolization can proceed. A variety of embolic materials have been used for preoperative portal vein embolization including coils, gelatin sponge, n-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), tris-acryl microspheres and ethanol. Nonabsorbable materials are preferred because surgery is usually performed weeks to months after PVE.

Fig. 7.3 This patient underwent a right portal vein embolization (PVE) in preparation for a right hepatectomy. Note the difference in size of the left hepatic lobe (a) before and (b) after PVE.

Transplantation

A cirrhotic liver will continue to be a breeding ground for new areas of HCC. A liver transplantation offers the patients not only a cure of their current malignancy, but also addresses the underlying liver dysfunction and predisposition for developing more cancer. Transplantation is a definitive treatment option reserved for early-stage HCC patients with cirrhosis, though they have to be transplant candidates. In most institutions, the Milan criteria is used to identify transplant candidacy. This takes into consideration the tumor size, number, and location (▸Table 7.5). In 1996, a paper published by Mazzaferro et al showed that outcomes for transplanted HCC patients that met this criteria were similar to cancer-free transplanted patients. The study is criticized for its limitations, and data published since then suggests that more inclusive criteria, allowing for somewhat larger tumors, do not adversely impact 5-year survival. The University of California San Francisco (UCSF) criteria is an alternative that takes this into account. For cancer and cancer-free patients alike, liver transplantation requires a great deal of planning and close follow-up. Transplantation is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 6.

Locoregional Therapy

The options for locoregional therapy include transarterial bland, chemo- or radioembolization, and ablation. In general, locoregional therapy is an option when a patient with HCC is not a transplant or resection candidate. In some patients who meet or are close to meeting transplant candidacy, these procedures can be used as adjunctive therapy until they are definitively treated with a new liver. In select cases, locoregional therapy itself can be potentially curative.

Single HCC < 5 cm, or up to three nodules < 3 cm each |

No evidence of gross vascular invasion |

No regional nodal or distant metastases |

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma. |

For patients who are just outside the Milan criteria for transplantation, the question then becomes whether the patient’s tumors can be sufficiently reduced in size and number to make them eligible for transplantation. If yes, therapy should be directed toward this goal. An example is a patient who has one 2-cm mass and one 4-cm mass, which puts him outside of the Milan criteria. If locoregional therapy is performed and the 4-cm mass decreases in size to 2.5 cm, the patient is now eligible for liver transplant. This is called “downstaging to transplant.”

If downstaging is not feasible, attention is turned toward prolonging life before the patient succumbs to the disease. Ablation and embolization can both be performed and repeated if necessary, with the aim of reducing or slowing disease progression, adding months or even years of survival.

Thermal ablation by radiofrequency (RFA) or microwave (MWA) is a good option for small (< 3–5 cm) HCC lesions. RFA and MWA involve percutaneous (occasionally laparoscopic or open surgical) insertion of a probe into the tumor and heating it to the point of necrosis (Procedure Box 7.3). Lesions larger than 3 cm can be ablated, but recurrence rates are higher. Generally speaking, ablation is avoided for central lesions very close to the confluence of bile ducts or in close proximity to blood vessels. Proximity to blood flow tends to limit ablation efficacy as the vessels cause a heat sink effect, keeping temperatures from reaching the desired therapeutic level. In select cases (an isolated, small HCC lesion), ablation can be curative.

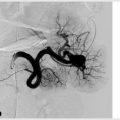

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) involves injecting chemotherapy into a branch of the hepatic artery feeding the tumor. The reason this works is because of the dual blood supply of the liver. Liver malignancies are supplied predominantly from the hepatic artery branches (> 80%), while normal liver parenchyma is supplied mostly by the portal vein. By selectively treating the arterial system, TACE can be used to target the cancer without causing major damage to the liver parenchyma (Procedure Box 7.4).

There are several different types of transarterial embolization, which differ based on materials used. In conventional TACE, the cocktail injected includes a chemotherapeutic drug, lipiodol, and an embolic substance.

The chemotherapeutic drug used for TACE varies, and no studies have concluded that one is definitely better than another. Options include some combination of emulsified doxorubicin, cisplatin, and mitomycin. Alternatively, an embolic agent can be used without any chemotherapy, which is called bland embolization. Yet another option is the use of drug-eluting beads (DEB-TACE), which slowly elutes a chemotherapy agent, often doxorubicin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree