Nonneoplastic Lesion of the Ovary

Cysts of Follicular Origin

During prepuberal and reproductive years, the functional follicle cysts and corpus luteum cysts measuring 3–10 cm in diameter are, by definition, benign. These lesions are often completely asymptomatic; most resolve spontaneously but may cause acute abdominal pain secondary to rupture and hemoperitoneum or torsion.

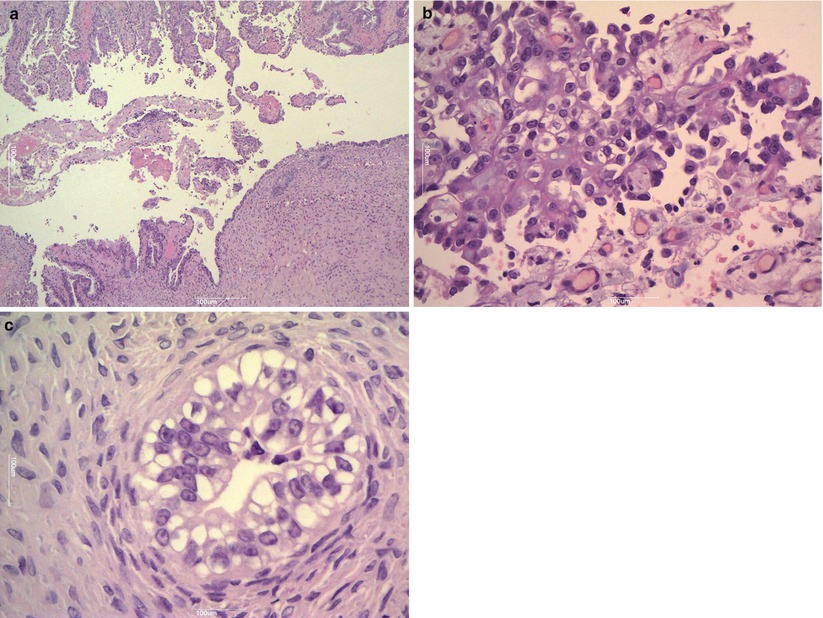

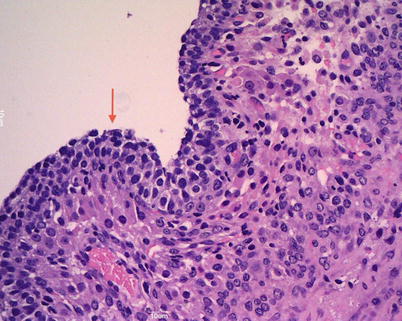

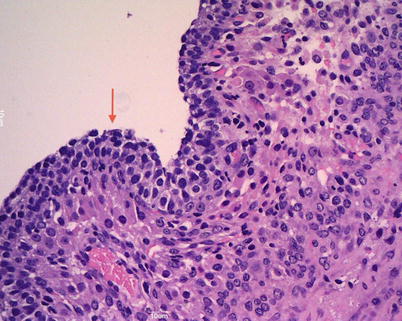

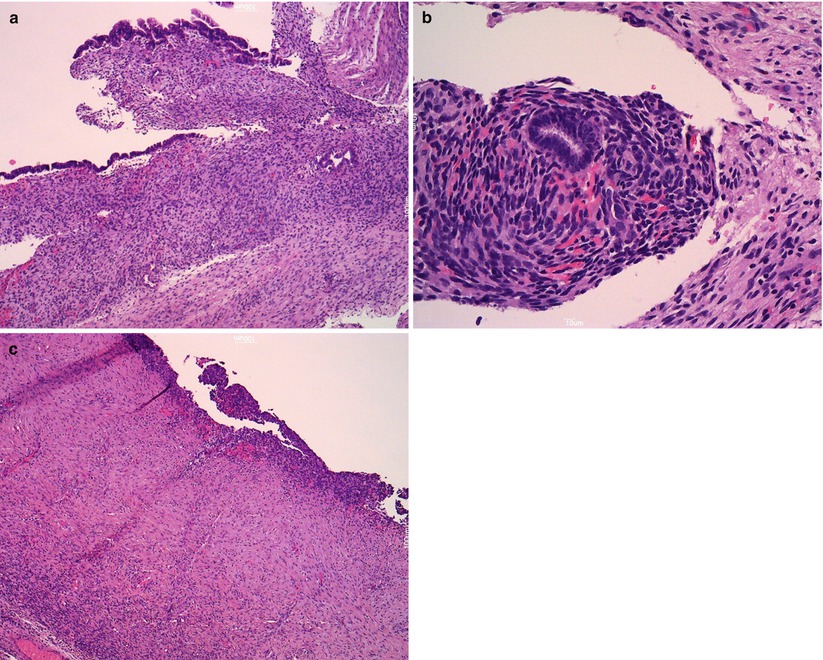

The cysts of follicular origin are solitary and fluid-filled. At microscopy follicular cysts are lined by granulosa cells, with a surrounding layer of theca cells (Fig. 1); both layers may show luteinization; corpus luteum cysts commonly contain intracystic hemorrhage, show a yellow rim of variable thickness, and are lined by a thick undulating layer of granulosa and theca cells, with prominent luteinization.

Fig. 1

Follicular cyst is lined by several layers of granulosa cells (arrow)

Differential Diagnosis

Cystic granulosa cell tumor

Surface epithelial cystoadenoma

Pregnancy Luteoma

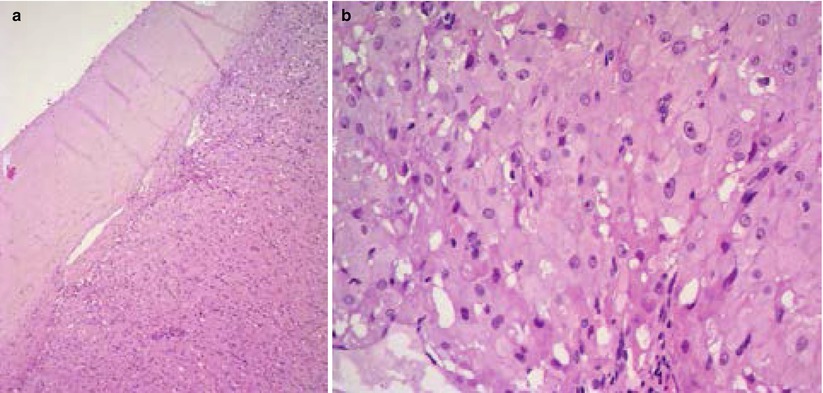

It can mimic an ovarian neoplasia both grossly and microscopically. These tumorlike lesions, more common in black women, are composed of luteinized cells occurring during pregnancy secondary to hormonal stimulations. Macroscopically, pregnancy luteoma presents as one or multiple (30 % are bilateral, 50 % are multiple) solid masses with multiple circumscribed nodules that show a red-brown cut surface. At microscopy, nodules are well-circumscribed and luteinized cells show abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, central and regular nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Fig. 2). Mitoses could be up to 7/10 HPFs. Necrotic and degenerative changes may be present. Usually pregnancy luteoma regresses after delivery.

Fig. 2

Pregnancy luteoma is composed of luteinized cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (a); central and regular nuclei and prominent nucleoli are present (b)

Differential Diagnosis

Steroid cell tumor

Leydig cell tumor

Thecoma

Endometrioma (Endometriotic Cyst)

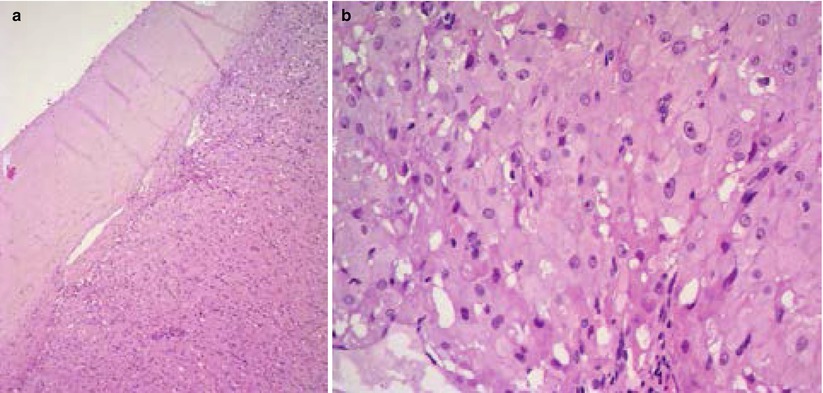

Ovarian endometriosis is a common finding and frequently gives to cystic masses (endometriomas): it is often bilateral and usually presents during the reproductive age. The macroscopic appearance is that of a large cystic mass (usually < 15 cm) with a thick wall that often replaces the ovary completely. Frequently, the ovarian surface is covered by dense fibrous adhesions. The intracystic material is dense and brown (“chocolate cyst”). The variable microscopic appearance is due to the different ectopic endometrial glands and stromal response to the hormonal milieu of the menstrual cycle. Endometrial glands surrounded by endometrial-type stroma may show inactive or proliferative, secretory, or atrophic changes (Fig. 3). Fibrosis and inflammation also interfere with macro- and microscopic features. Often, in non-recent cases, where we cannot find a well-defined glandular or stromal structure, the histological diagnosis is suggested by indirect signs including granulation tissue, macrophages, and siderophages (Fig. 4). Foci with epithelial atypia are often detected (atypical endometriosis), but they should not be mistaken for malignant transformation. Ancillary immunohistochemical studies may help to detect endometrial stroma and glandular structures.

Fig. 3

Endometriosis. Endometriotic cyst is lined by endometrial-type epithelium (a); endometrioid gland is surrounded by endometrial-type stroma (b); atrophic changes of epithelium (c)

Fig. 4

Granulation tissue macrophages and siderophages (arrow) in endometrioma

Differential Diagnosis

Benign hemorrhagic cyst of follicular origin

Chronic tubo-ovarian abscesses

Cystoadenomas

Unilocular granulosa cell tumors

Secondary neoplasm (clear cell or endometrioid carcinoma)

Ovarian Tumors

Ovarian tumors, according to the WHO classification (2003), can be primary or secondary (metastatic). Primary ovarian tumors arise from surface müllerian epithelium or from sex cord-stroma or from germ cells.

Surface Epithelial Tumors of the Ovary

Surface epithelial tumors are the most common neoplasms of the ovary. They may arise from the surface epithelium, from the fallopian tube epithelium, or from preexistent ovarian endometriosis. Surface epithelial tumors are classified into serous (46 %), mucinous (36 %), endometrioid (8 %), clear cells (3 %), transitional (2 %), undifferentiated (2 %), and mixed (3 %) on the basis of their different cell type. Histological features allow us to subclassify these tumors as benign, borderline and malignant. By definition, the borderline tumors lack destructive stromal invasion but show other histological features of malignancy (nuclear atypia, cellular stratification, mitotic activity). Their clinical behavior is mostly benign but, caveat, as far as serous borderline surface tumors are concerned, they are frequently associated with extraovarian disease and present a clinical behavior intermediate between benign tumors and invasive serous carcinomas.

Tumor stage, according to FIGO, is the most important prognostic factor; stage can only be assigned after completion of a proper surgical staging procedure. Tumor grading is done on the basis of architectural and cytologic atypia; mitotic count is another prognostic factor, but its prognostic value and reproducibility remain to be determined.

Serous Surface Epithelial Tumors

Serous Cystoadenoma, Cystoadenofibroma, and Adenofibroma

It is the most common serous benign ovarian neoplasm (50 %), occurs in the reproductive age, is composed of varying amounts of fibrous stroma and cysts and is subclassified by the WHO in serous cystoadenoma, cystoadenofibroma, and adenofibroma. These tumors range in size from 1 to 10 cm and are bilateral in 20 % of the cases. Smooth-walled unilocular or multilocular cysts are lined by nonstratified tubal-type epithelium. Epithelial cells do not show nuclear atypia, mitoses and necrosis. Torsion, rupture, and infection are the most common complications.

Differential Diagnosis

Epithelial inclusion cyst

Ovarian rete cyst

Endometriotic cyst

Struma ovarii

Serous borderline tumor

Mucinous cystoadenoma

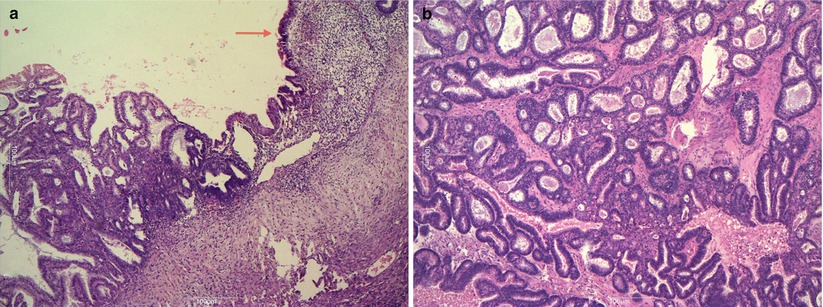

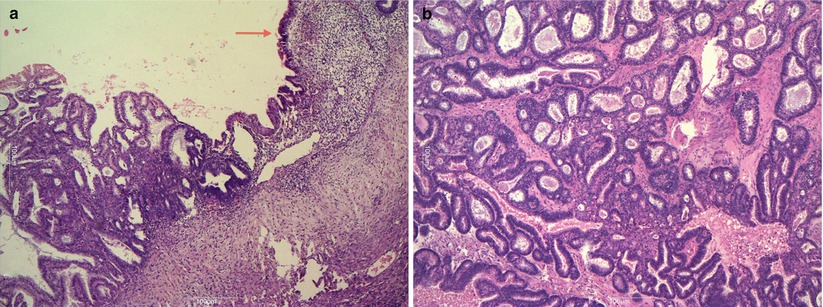

Serous Borderline Tumor (Serous Tumor of Low Malignant Potential)

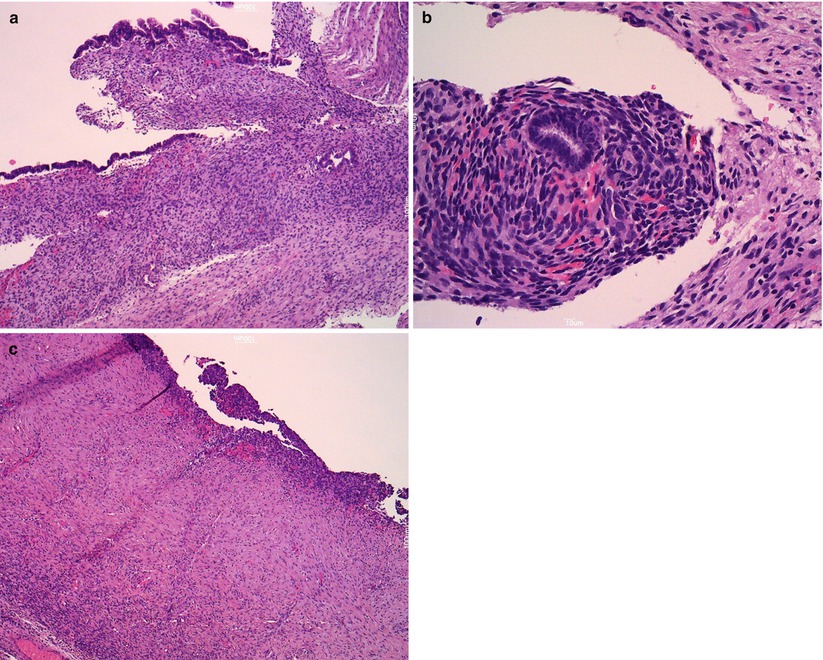

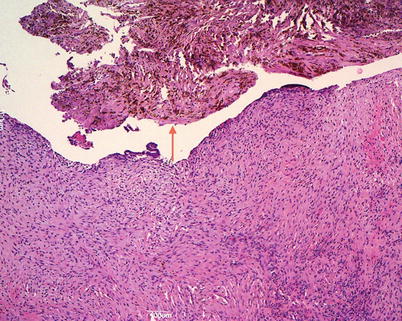

Serous borderline tumors occur more frequently during the fourth and fifth decades and usually in the reproductive age. They form bilateral (30–40 %) large cystic or solid and cystic masses with surface papillary epithelial structures. The inner layer of the cyst is composed of large and small confluent papillae with complex hierarchical branching (Fig. 5). The lining cells are tall to columnar with stratification, mild–moderate atypia, and sparse mitoses (Fig. 6). Psammoma bodies can be present. Foci of stromal microinvasion (<10 mm2) do not warrant a diagnosis of carcinoma. Extraovarian peritoneal and lymph node implants may be present at the time of detection. The extraovarian serous implants are classified according to the WHO as invasive or noninvasive, epithelial or desmoplastic, on the basis of the interface between the implant and normal tissue. The micropapillary variant of serous borderline tumors is more frequently associated with bilaterality, ovarian surface involvement and extraovarian implants, some of which may be invasive. The course of disease is indolent. Tumor stage is an important prognostic factor; invasive extraovarian implants confer a comparatively poor prognosis. Serous borderline tumor cells are immunoreactive for CK7, EMA, WT1, CA125 while are CK20 negative. Point mutations in BRAF or K-RAS are frequently associated with serous borderline tumors, but no association with germ line or somatic BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations has been reported.

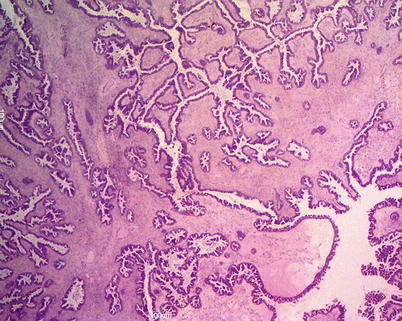

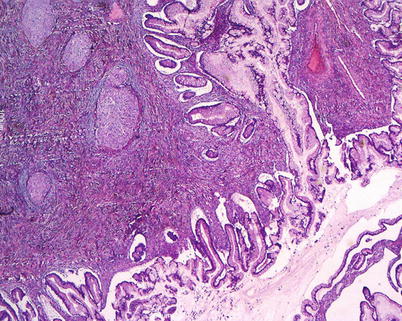

Fig. 5

Serous borderline tumor: the inner layer of the cyst is composed of large and small confluent papillae with complex hierarchical branching

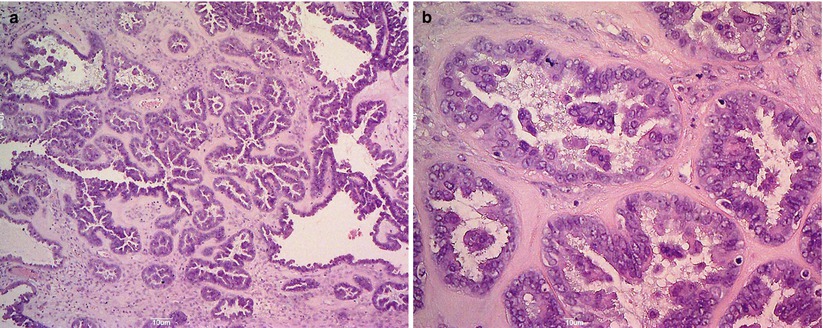

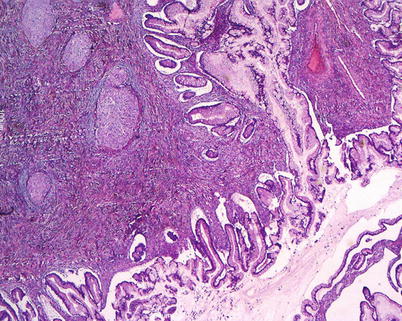

Fig. 6

Serous borderline tumor: the lining cells are tall to columnar with stratification (a); mild–moderate atypia and sparse mitosis are present (b)

Differential Diagnosis

Serous borderline tumor with focal proliferation

Serous adenocarcinoma

Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma

Struma ovarii

Mucinous borderline tumor, endocervical type

Serous Adenocarcinoma

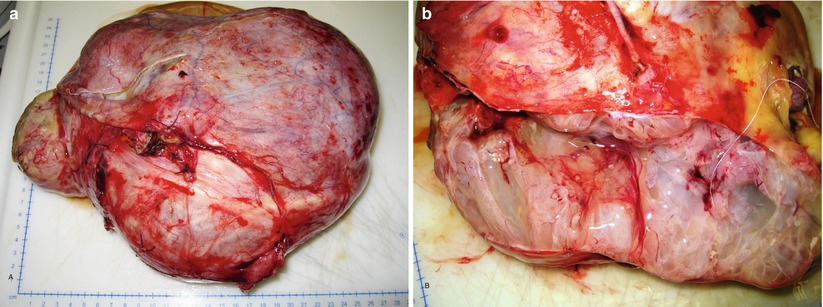

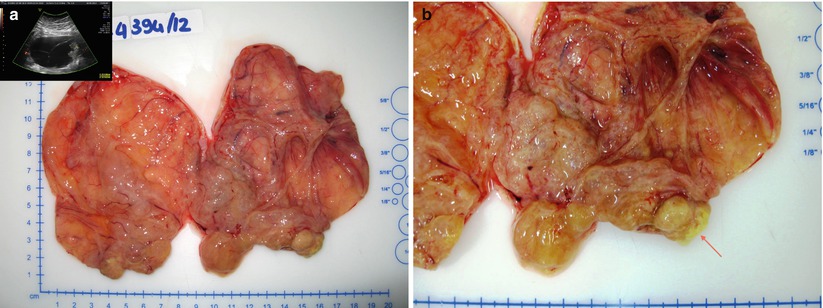

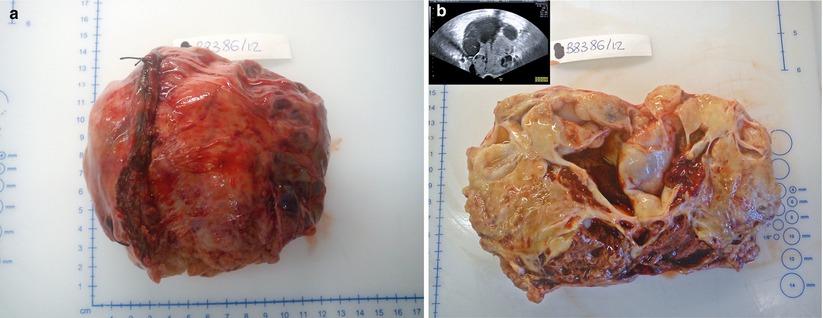

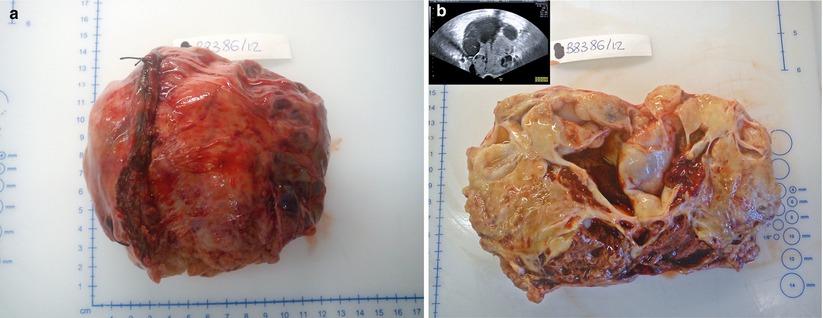

Serous carcinoma comprises 35 % of all ovarian tumors, the incidence peak being in the sixth to seventh decades. At the time of diagnosis, pelvic ovarian masses, peritoneal spread and ascites are present. Serous carcinoma forms solid and cystic masses (Fig. 7) that frequently show areas of necrosis and hemorrhage. At microscopy, complex papillae, glands with malignant cellular stratification, and psammoma bodies are observed. The immunohistochemical profile is similar to that typically found in benign and borderline serous tumors. Grading, from 1 to 3 according to the WHO, is based on architectural features and nuclear atypia (Fig. 8). Molecular studies show somatic or germ line abnormalities of BRCA1/BRCA2 genes in high-grade tumors. In contrast, low-grade serous carcinoma shows a molecular profile similar to that of serous borderline tumors (BRAF or K-RAS mutation).

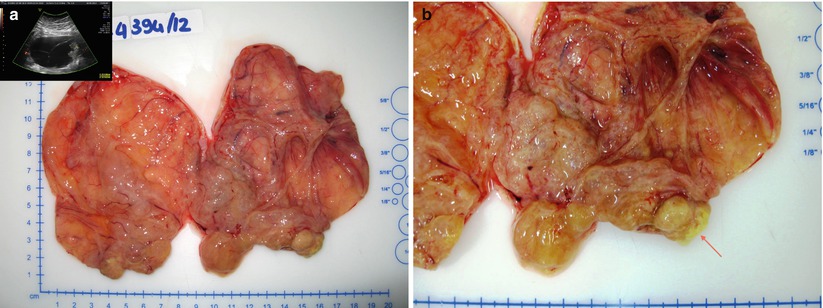

Fig. 7

Bilateral serous adenocarcinoma: solid masses replace both ovaries (a); cut surface shows also areas of necrosis; perfect concordance with the transvaginal scan (b)

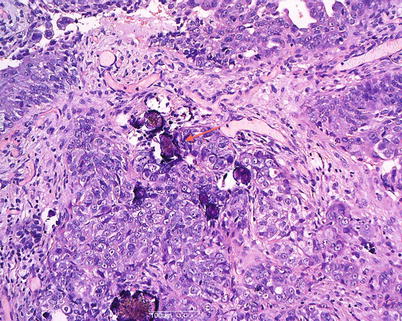

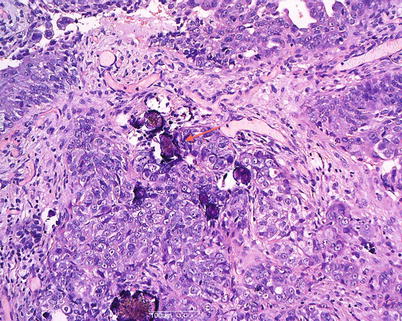

Fig. 8

High-grade serous carcinoma: solid growth with marked cytologic atypia and psammoma bodies (arrow)

Differential Diagnosis

Serous borderline tumor

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma

Clear cell carcinoma

Transitional cell carcinoma

Primary peritoneal serous carcinoma

Peritoneal papillary mesothelioma

Metastatic serous carcinoma of endometrium

Metastatic breast carcinoma

Mucinous Surface Epithelial Tumors

Primary ovarian mucinous tumors include cystoadenomas, borderline or low malignant potential tumors, and carcinomas (intraepithelial and invasive). Cystoadenomas and borderline tumors are, by definition, noninvasive and are distinguished by their degree of complexity and epithelial proliferation. Frequently, in the same tumor there is a morphologic spectrum of epithelial proliferations which include benign, borderline, and malignant features; therefore, an appropriate histological sampling is very important for a correct diagnosis. Mucinous tumors with the same histological features can also occur in extraovarian sites; ovarian metastases from tumors of gastrointestinal and biliary tract can simulate primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma. Even with the aid of ancillary immunohistochemical techniques, and in expert hands, distinction of primary from metastatic mucinous carcinoma may be very difficult. Mucinous epithelial tumors may coexist with Brenner tumors (Fig. 9): it has been suggested that the majority of intestinal-type mucinous tumors arise from Brenner tumors or transitional cell nests.

Fig. 9

Mixed tumor: mucinous borderline tumor, intestinal type, and benign Brenner tumor

Benign Mucinous Tumors (Cystoadenoma, Cystoadenofibroma, and Adenofibroma)

Benign mucinous tumors are composed of intestinal-type or endocervical-like mucinous epithelium. They account for the majority of mucinous ovarian tumors (80 %). They are unilocular or multilocular tumors of variable size, ranging from a few to over 30 cm. They are typically unilateral; the capsula is thick and white with a smooth outer surface. Mucinous cysts contain gelatinous material and are composed of glands and cysts lined by columnar, pale-staining epithelium; stratification and atypia are absent (Fig. 10).

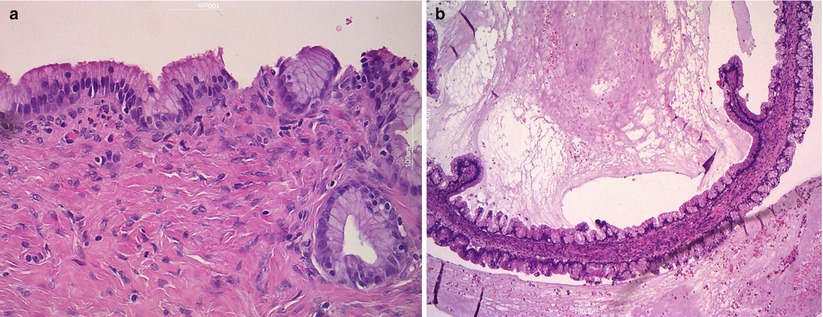

Fig. 10

Mucinous cystoadenoma. The cysts are lined by simple nonstratified mucinous epithelium (a) and contain thick gelatinous material (b)

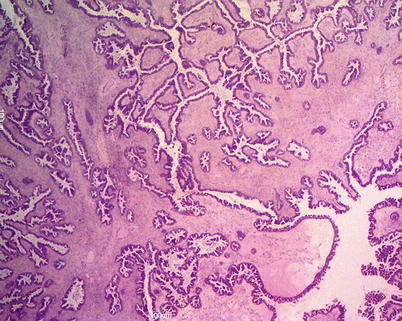

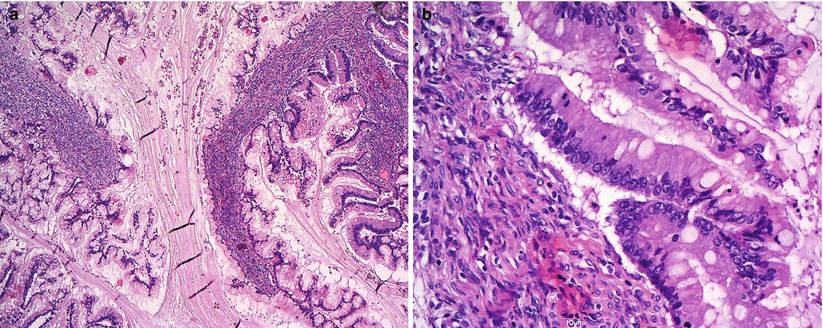

Mucinous Borderline Tumor (Mucinous Tumor of Low Malignant Potential)

Two histological types of mucinous borderline tumors are distinguished: intestinal type and endocervical-like. The first type (Fig. 11) is a large, multicystic and unilateral (>95 %) tumor lined by stratified intestinal-type epithelium with papillary intraglandular growth, mild to moderate nuclear atypia, and rare mitoses. Stromal invasion is absent (Fig. 12). Intestinal-type mucinous borderline tumors at immunohistochemistry are CEA positive, CA125 negative, CK7 and CK20 positive. At presentation, most of them are stage I and have a benign clinical course. Patients with associated peritoneal implants, foci of intraepithelial carcinoma, or stromal microinvasion have an excellent prognosis (100 % survival). Recent studies show that advanced stage intestinal-type mucinous borderline tumors with adverse outcome represent in fact metastases from occult extraovarian primary tumors.

Fig. 11

Mucinous borderline tumor, intestinal type: large ovarian mass (a); multiloculated cysts contain mucoid material (b)

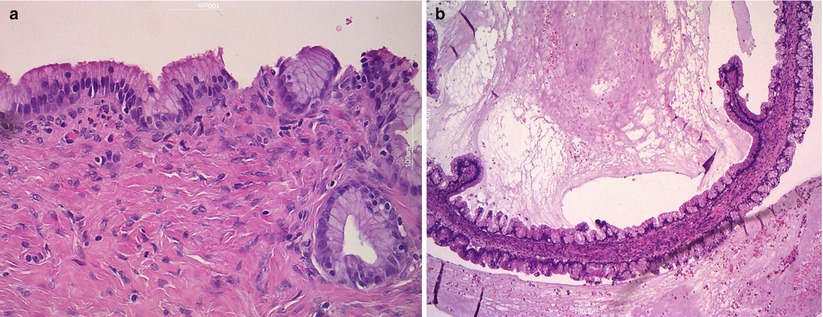

Fig. 12

Mucinous borderline tumor, intestinal type: complex papillary folds (a); intestinal-type epithelium with goblet cells, mild to moderate cytologic atypia, and focal mitoses (b)

Differential Diagnosis

Mucinous cystoadenoma with focal proliferation

Mucinous adenocarcinoma

Metastatic adenocarcinoma (appendix, colon, stomach, pancreatobiliary tract, cervix, lung)

In contrast to intestinal-type mucinous borderline tumors, endocervical-like neoplasms are less common, usually smaller, frequently bilateral and associated with endometriosis. Tumor cells are CK7 positive and CK20 negative. These tumors are often admixed with a component of serous borderline tumor.

Differential Diagnosis

Serous borderline tumor

Mucinous borderline tumor, intestinal type

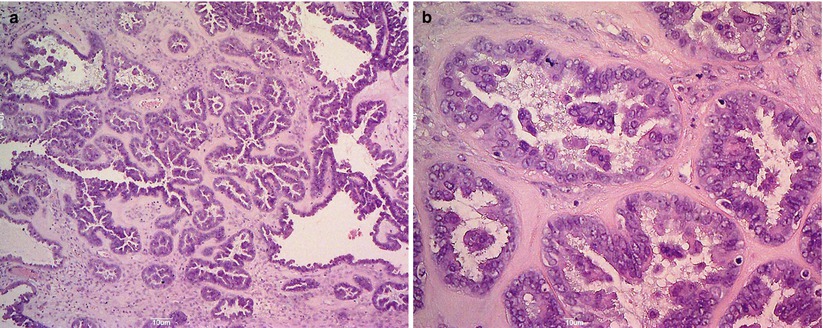

Mucinous Adenocarcinoma

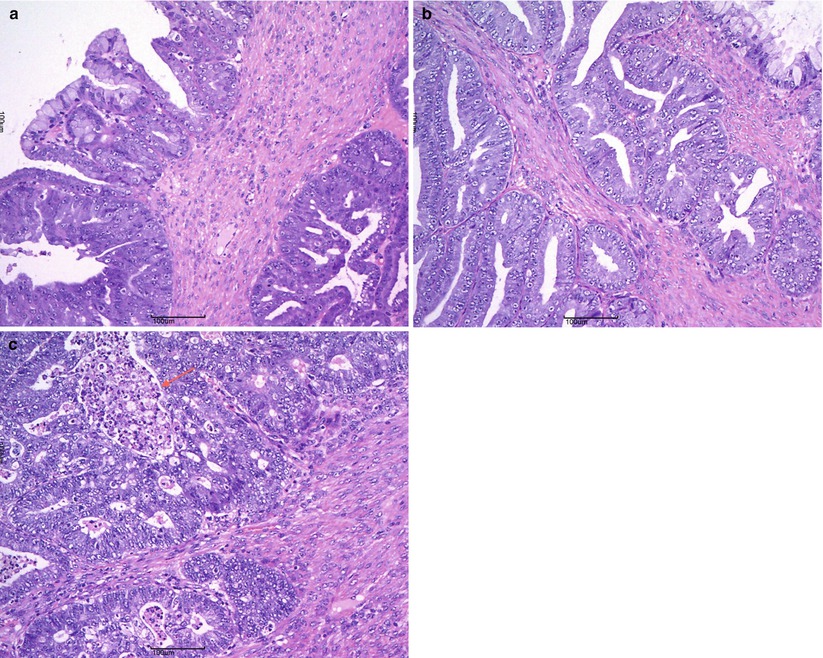

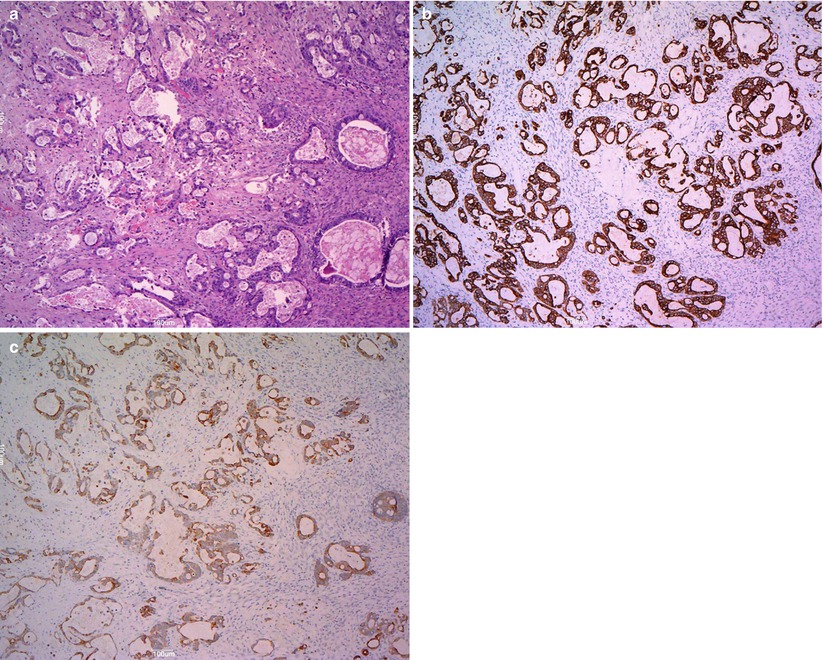

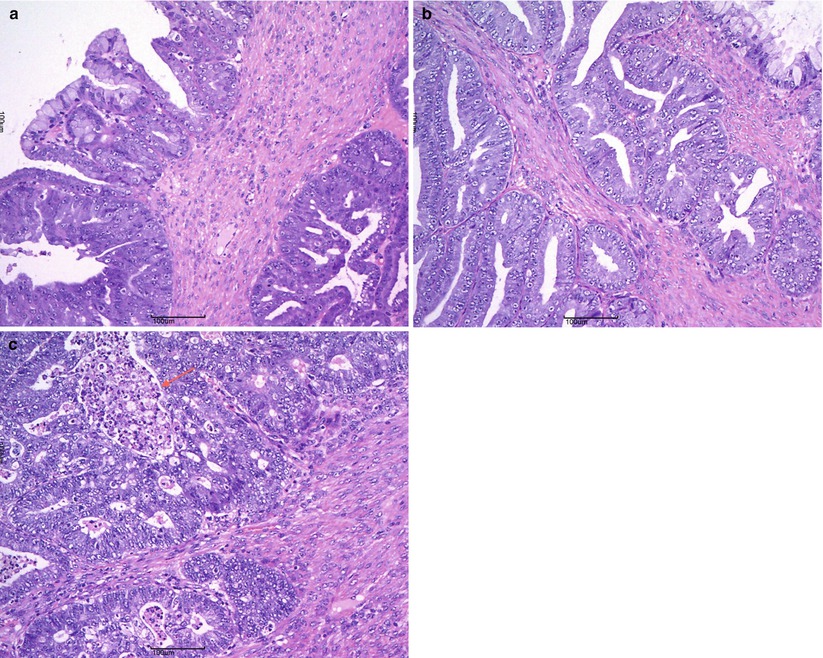

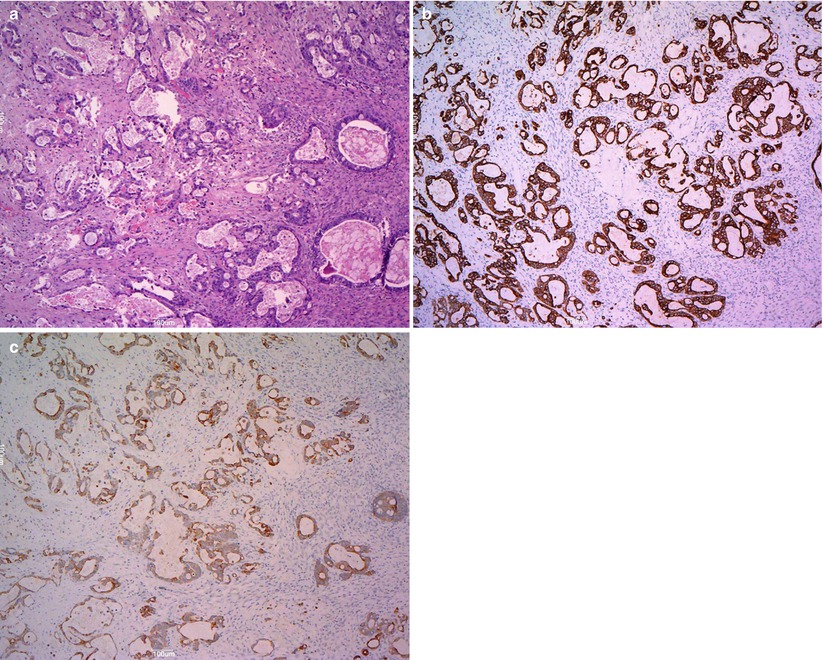

Mucinous adenocarcinomas are <15 % of all mucinous ovarian tumors and most of them are stage I at presentation. The tumoral masses are solid and cystic and may contain foci of necrosis and hemorrhage (Fig. 13). Ovarian surface involvement is rare but large tumors may present capsular rupture. Different patterns of stromal invasion can be recognized in intestinal-type adenocarcinoma: (1) confluent or expansile pattern (complex, crowded, confluent glands with cytologic atypia and little stroma) (Fig. 14); (2) infiltrative and destructive pattern (Fig. 15), more frequent in metastatic tumors. Areas of benign, borderline, and invasive mucinous carcinoma coexist in the same tumor (Fig. 16). Immunohistochemical profile is similar to that of borderline tumors (CK7+, CK20+, CEA+). The stage is the most important prognostic factor. Grading of mucinous carcinomas has not been precisely defined yet, but the nuclear features are the best discriminator; tumors with glandular and papillary architecture are low grade.

Fig. 13

Mucinous carcinoma: on cut surface the tumor is partly cystic multiloculated filled with mucoid material (perfect concordance with the transvaginal scan) (a) partly solid with areas of necrosis (arrow) (b)

Fig. 14

Mucinous carcinoma: expansile pattern of invasion (a); complex interconnecting neoplastic glands (b); cribriform pattern with marked cytologic atypia and necrotic debris in gland lumens (arrow) (c)

Fig. 15

Mucinous carcinoma: infiltrative pattern of stromal invasion (a); the tumor cells show strong and diffuse positivity for CK20 (b) and CK7 (c)

Fig. 16

Mucinous carcinoma: areas of borderline tumor adjacent to areas of carcinoma

Differential Diagnosis

Metastatic adenocarcinoma (appendix, colon, stomach, pancreatobiliary tract, cervix, lung)

Mucinous borderline tumor

Mucinous Tumors Associated with Pseudomyxoma Peritonei (PMP)

Mucoid noninvasive nodules adherent to peritoneal surface characterize PMP. Low-grade neoplastic mucinous epithelium with pools of extracellular mucin and fibrosis is their typical morphologic appearance. Many studies show that all cases of PMP derive from low-grade mucinous tumors of the appendix and that ovarian involvement is secondary (“metastatic mucinous tumor”).

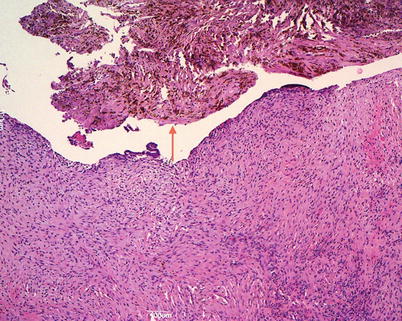

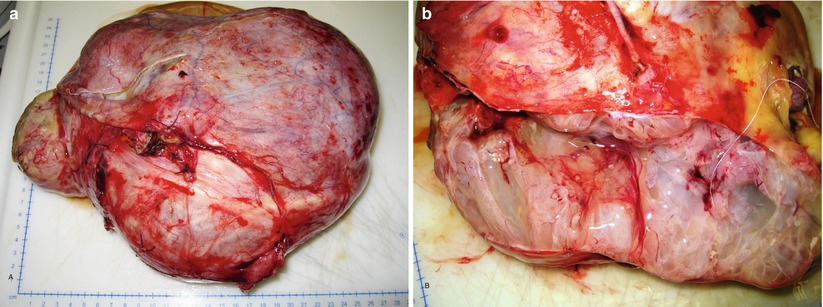

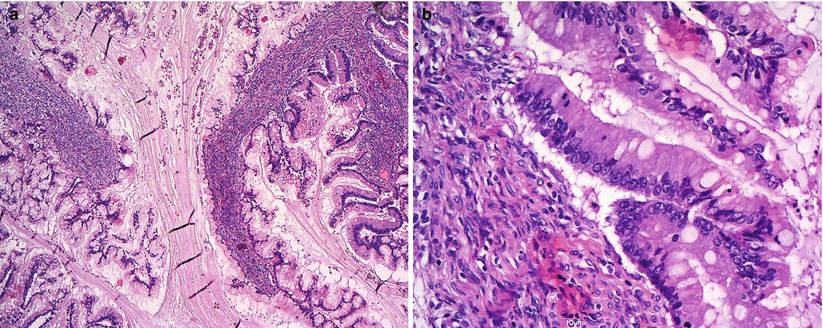

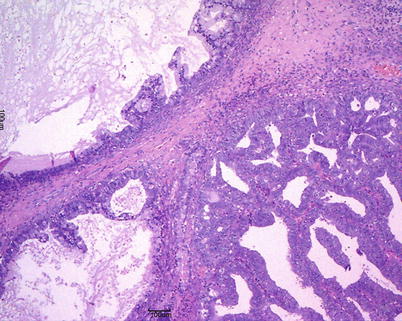

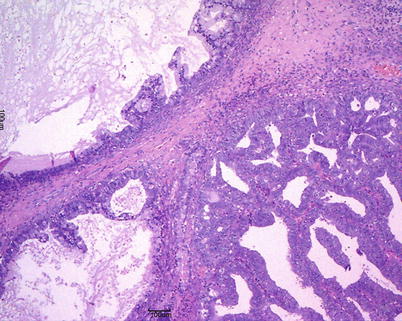

Endometrioid Surface Epithelial Tumors

The majority of endometrioid ovarian tumors are carcinomas (75 %). Benign and borderline endometrioid tumors are uncommon. Many of them arise from malignant transformation of ovarian endometriosis (Fig. 17). Endometrioid carcinomas are associated with synchronous low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium in 15–20 % of cases. Borderline tumors and carcinomas may be monolateral or bilateral; they can be cystic with intracystic solid nodules. Areas of hemorrhage and necrosis are found in carcinomas. Endometrioid tumors are composed of endometrial-type glands and stroma. Endometrioid borderline tumors, according to the WHO classification, are composed of atypical endometrioid-type glands in a dense stroma without stromal invasion. Ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma is usually comparable to FIGO grade 1 or 2 endometrioid endometrial carcinoma (Fig. 18) and grading system is the same as for endometrial carcinoma; squamous metaplasia is common. At immunohistochemistry, endometrioid tumors are positive for CK7, ER and PR, negative for CK20, alpha-inhibin and calretinin. The most common genetic abnormalities in sporadic ovarian endometrioid carcinoma are somatic mutations of beta-catenin and PTEN.

Fig. 17

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma: large unilateral ovarian mass with capsule rupture (a); on cut surface the tumor shows cystic and solid areas, hemorrhage and necrosis; the transvaginal scan shows the same large ovarian multilocular-solid tumor (b)

Fig. 18

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma associated with endometriosis (arrow) (a); FIGO grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma (b)

Differential Diagnosis

Serous adenocarcinoma

Sex cord-stromal tumors

Carcinoid tumor

Metastatic colorectal or endometrial carcinoma

Polypoid endometriosis

Diffuse granulosa cell tumor

High-grade carcinoma

Clear Cell Surface Epithelial Tumors

The vast majority of clear cell surface epithelial tumors are malignant (99 %). Benign and borderline clear cell adenofibromatous tumors are very rare and are composed of firm tissue with small cysts (Fig. 19), showing, on cut surface, a fine honeycomb appearance. Clear cell carcinomas present frequently as a unilocular cyst containing a solid mass with foci of necrosis and hemorrhage (Fig. 20). Clear cell carcinomas are frequently associated with endometriosis (70–80 %), and one-fourth of cases arise in endometriotic cysts as a single fleshy nodule. Tumor architecture is usually an admixture of tubulocystic, papillary, and solid patterns. At microscopy clear cell tumors are composed of epithelial cells with abundant glycogen-rich cytoplasm and hobnail cells with scant cytoplasm and nuclei protruding into the lumens of cystic spaces (Fig. 21). All clear cell carcinomas are considered high grade.

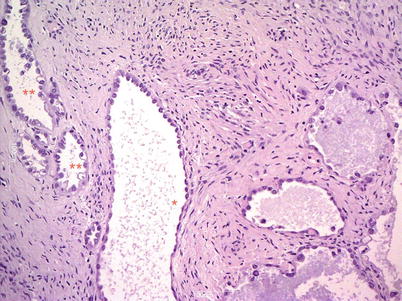

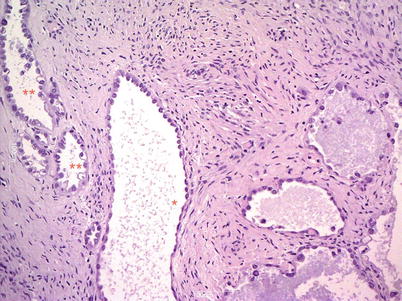

Fig. 19

Borderline clear cell adenofibroma: cystic glands, separated by fibromatous stroma, are lined by flat or hobnail cells with clear cytoplasm (**)

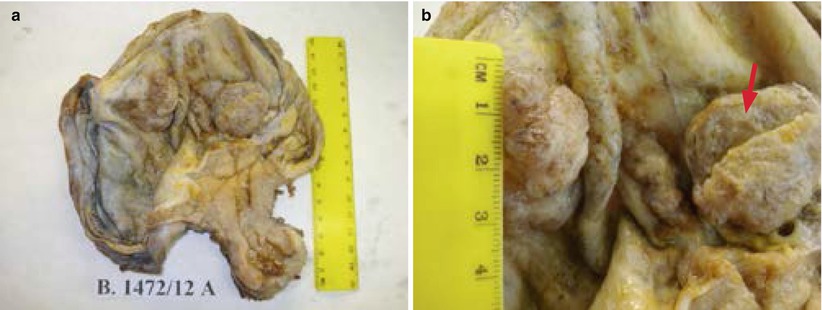

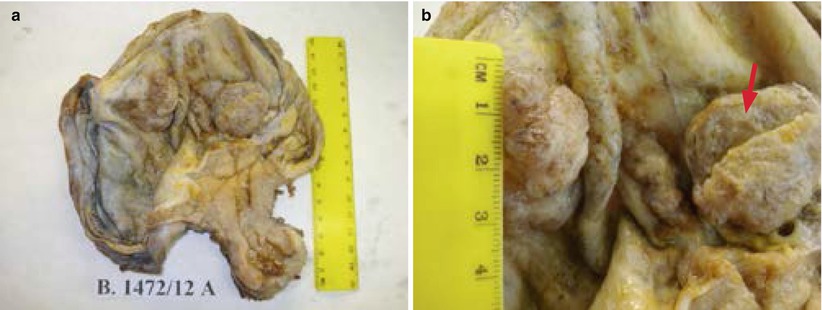

Fig. 20

Clear cell carcinoma associated with endometriosis: fleshy nodules in an endometriotic cyst with capsular adhesion to the uterus (a); the cut surface of nodules (arrow) shows microcystic appearance (b)