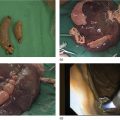

Shannon Melissa Chan and Anthony Yuen Bun Teoh Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong Acute cholecystitis has been managed with laparoscopic cholecystectomy in surgically fit patients. In patients who are high‐risk surgical candidates, percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PT‐GBD) has traditionally been the treatment of choice [1,2]. In recent years, internal drainage of the gallbladder using an endoscopic ultrasound‐guided transmural approach has emerged as a feasible and safe alternative [3–5]. Technical and clinical success were achieved in 95.3% and 90.8% of patients, respectively [6]. The technique was first described in 2007 [7]. In initial studies, the gallbladder was drained with transmural nasobiliary drainage tubes or plastic stents [8,9]. In recent years, the development of lumen‐apposing metal stents (LAMS) has gained widespread popularity due to the ease of deployment and lower concern for bile leakage [3,5,10]. LAMS also allows for subsequent advanced procedures such as stone removal [11]. According to the latest Tokyo Guidelines 2018, endoscopic ultrasound‐guided gallbladder drainage (EUS‐GBD) could be considered an alternative in high‐volume centers when performed by skilled endoscopists [12]. Certain technical aspects and controversies with EUS‐GBD are discussed in this chapter. The gallbladder can be drained with the EUS transmural approach via the antrum or duodenum. In other words, a cholecystogastric or cholecystoduodenal anastomosis is being created endoscopically. However, the gallbladder and the antrum or duodenum are inherently separate organs that are not adhered to each other. Therefore, there is a risk of stent migration, bile leakage, and pneumoperitoneum. Therefore, the puncture site and choice of stent determine the integrity of the anastomosis, and thus the success of the procedure. Initial studies reported the use of EUS‐guided insertion of nasocholecystic drains [8,9]. A cholecystogram was performed 48–72 hours later after sepsis subsided, and the nasocholecystic drain was exchanged for a double pigtail or was removed. When compared to PT‐GBD, EUS‐GBD with nasocholecystic drain showed similar rates of technical (97% vs. 97%) and clinical (100% vs. 96%) success [13]. The median postprocedure pain score was significantly lower after EUS‐GBD than after PT‐GBD [13]. This may be preferable in patients in whom cholecystectomy is contemplated in the future. However, plastic stents are easily occluded due to the narrow lumen. Fully covered self‐expandable metal stents have a larger lumen than plastic double pigtail stents. However, they are not designed for transluminal drainage and do not have tissue apposition ability. Thus, they are prone to stent migration and may result in leakage and peritonitis. LAMS were designed for transluminal drainage. All LAMS presently available on the market are initially intended for drainage of pancreatic fluid collections. They were designed with properties of tissue apposition and a large lumen to prevent stent occlusion. They are made of braided nitinol mesh with widely flared or dumbbell‐shaped flanges. All models are also covered with silicone membrane. Covered stents help to prevent leakage of air and bile. The silicone lining also impedes tissue ingrowth, making LAMS easily removable when needed [14]. LAMS that are currently available in the market are listed in Table 46.1. The larger lumens of LAMS allow for quick and effective drainage of infectious material and allows for further transluminal interventions via the stent in the gallbladder. A range of different diagnostic and interventional procedures through the stent, such as magnifying endoscopy, laser lithotripsy and basket mechanical lithotripsy for stone clearance, have also been reported in the gallbladder [11]. Table 46.1 Currently available LAMS on the market. Several studies comparing EUS‐GBD and PT‐GBD have been published [15–18]. The two procedures have similar rates of technical (EUS‐GBD 85.7–96.6% vs. PT‐GBD 99–100%) and clinical success (EUS‐GBD 89.8–95% vs. PT‐GBD 86–94.9%) [15,16,18]. PT‐GBD has been shown to be associated with more adverse events and more unplanned admissions [16], and also to have a higher need for reintervention [15]. In addition, a meta‐analysis that included five comparative studies (206 patients in the EUS‐GBD group vs. 289 patients in the PT‐GBD group) concluded that EUS‐GBD had fewer adverse events than PT‐GBD (odds ratio [OR] 0.43, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.18–1.00; P = 0.05; I2 = 66%), shorter hospital stays with pooled standard mean difference of –2.53 (95% CI –4.28 to –0.78; P = 0.005; I2 = 98%), and required significantly fewer reinterventions (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.04–0.042; P <0.001; I2 = 32%) resulting in significantly fewer unplanned readmissions (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.05–0.53; P = 0.003; I2 = 79%) [19]. LAMS can be inserted by delivery systems that are with or without cautery enhanced tip. For LAMS without a cautery tip, the conventional method of EUS‐guided insertion is required. The procedure is as follows. Thus, these points should be considered when deciding on the site for drainage of the gallbladder.

46

How to do EUS Gallbladder Drainage

Introduction

Background concept

Choice of stents: metal stents versus plastic stents

Stent

Brand

Introducer diameter (Fr)

Internal diameter (mm)

Flange diameter (mm)

Saddle length (mm)

Cautery tip delivery system available

Axios

Boston Scientific

10.8

10/15/20

21/24/29

10/10/10

Yes

Spaxus

Taewoong

10

10/16

23/25/31

20

Yes

Hanarostent

M.I.Tech

10.5

10/12/14 16

22/24/26/28

10/30

No

EUS‐GBD with LAMS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree