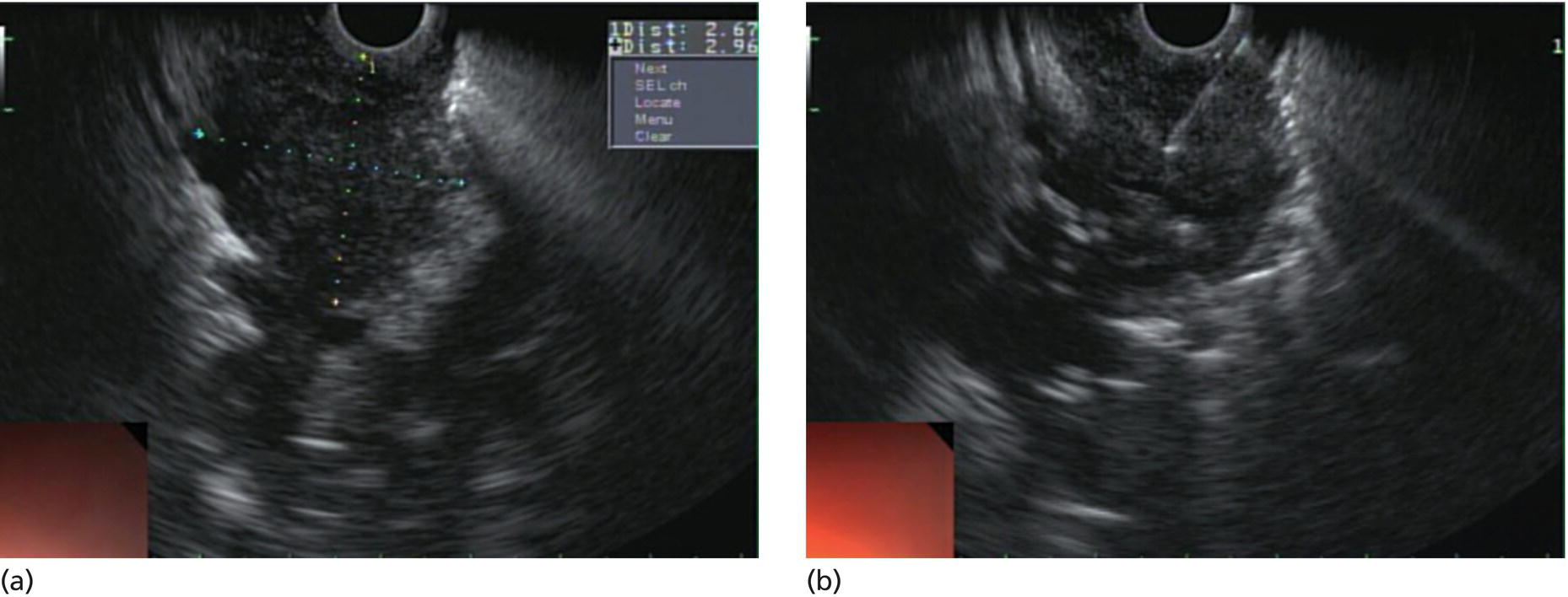

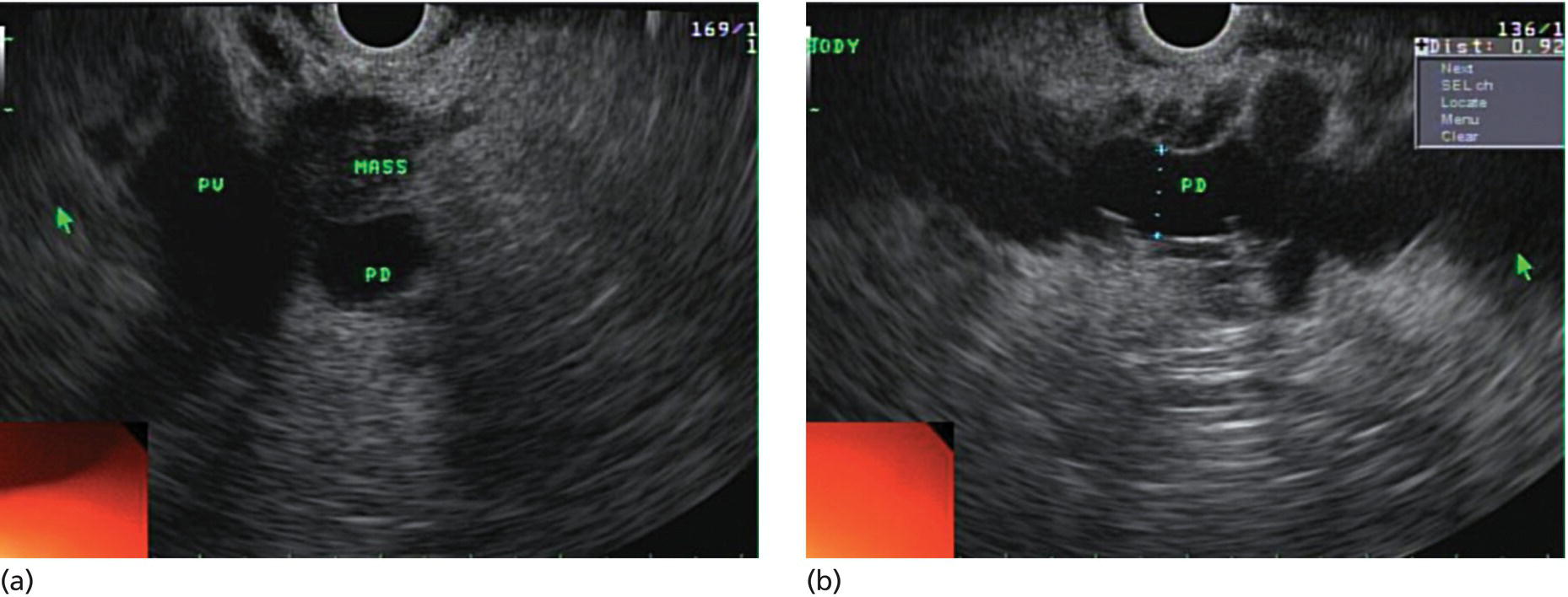

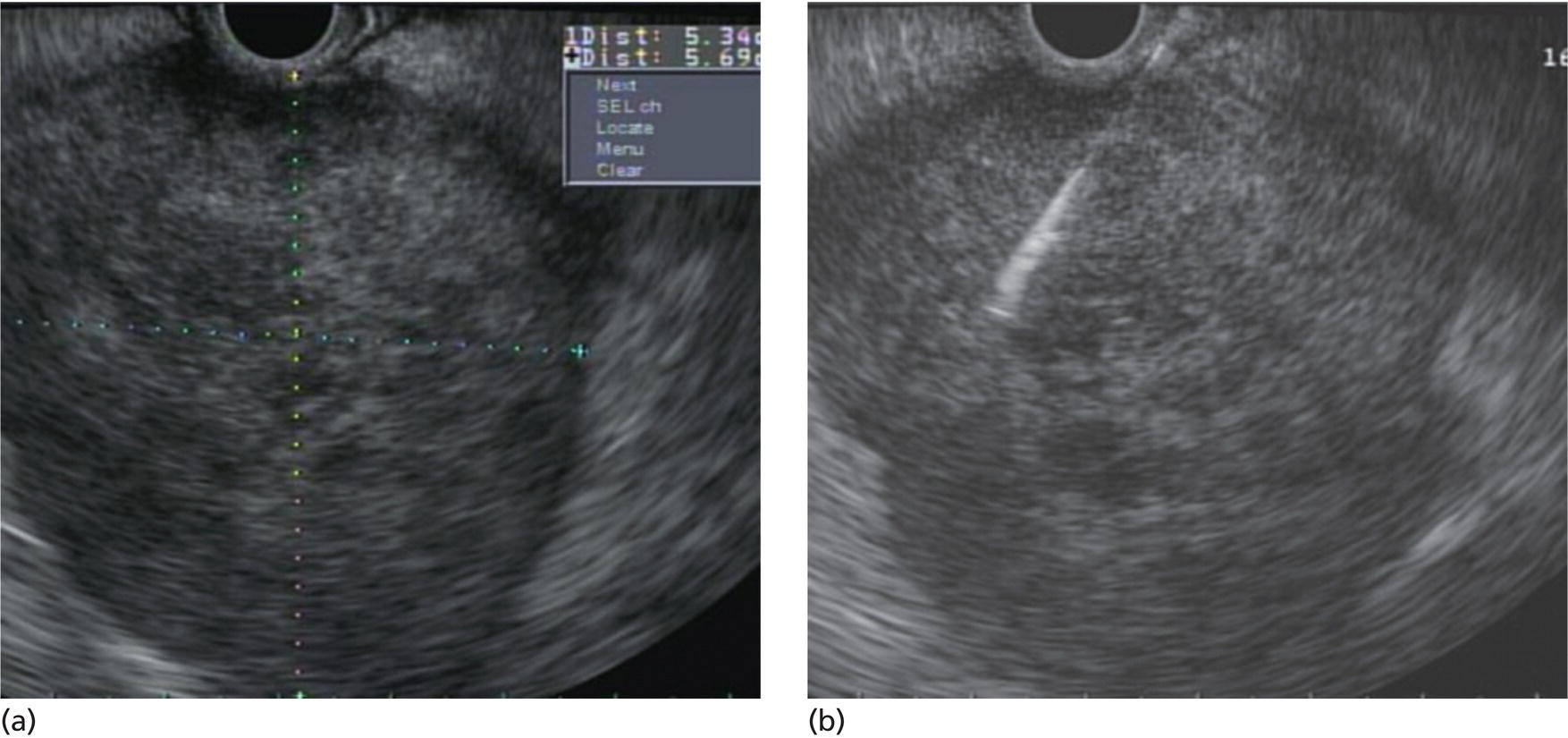

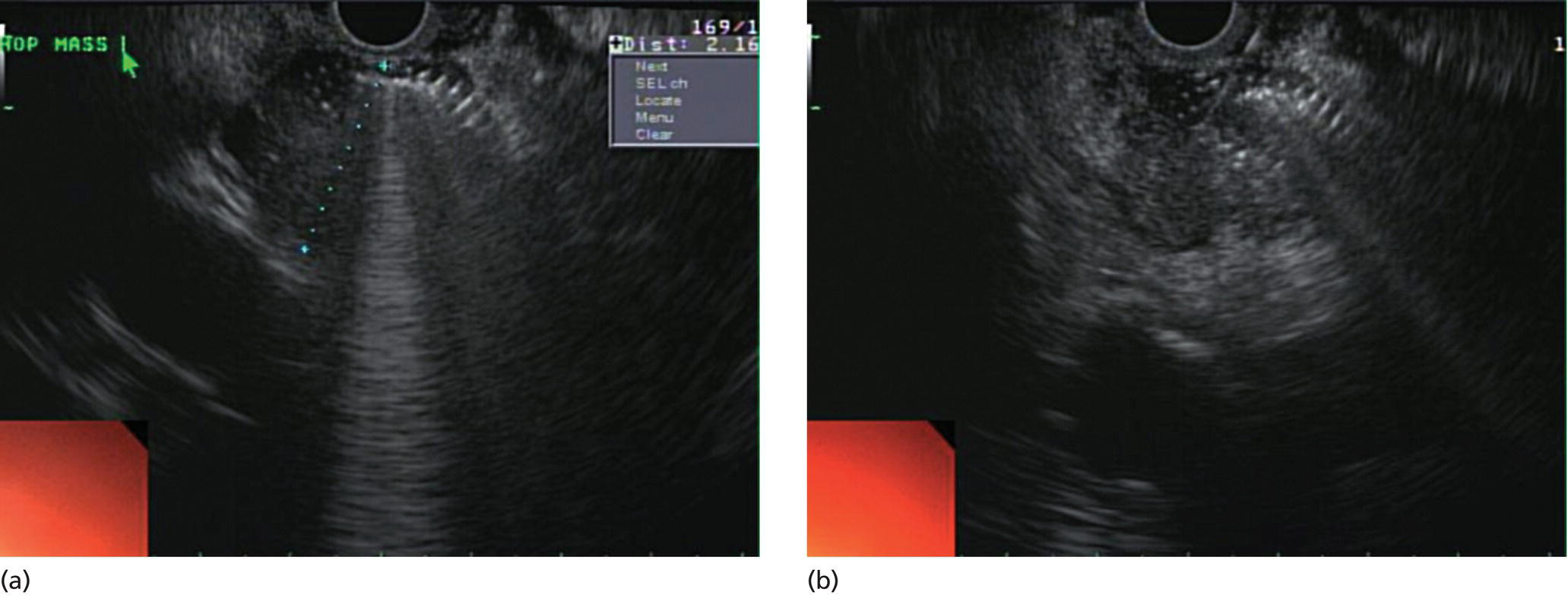

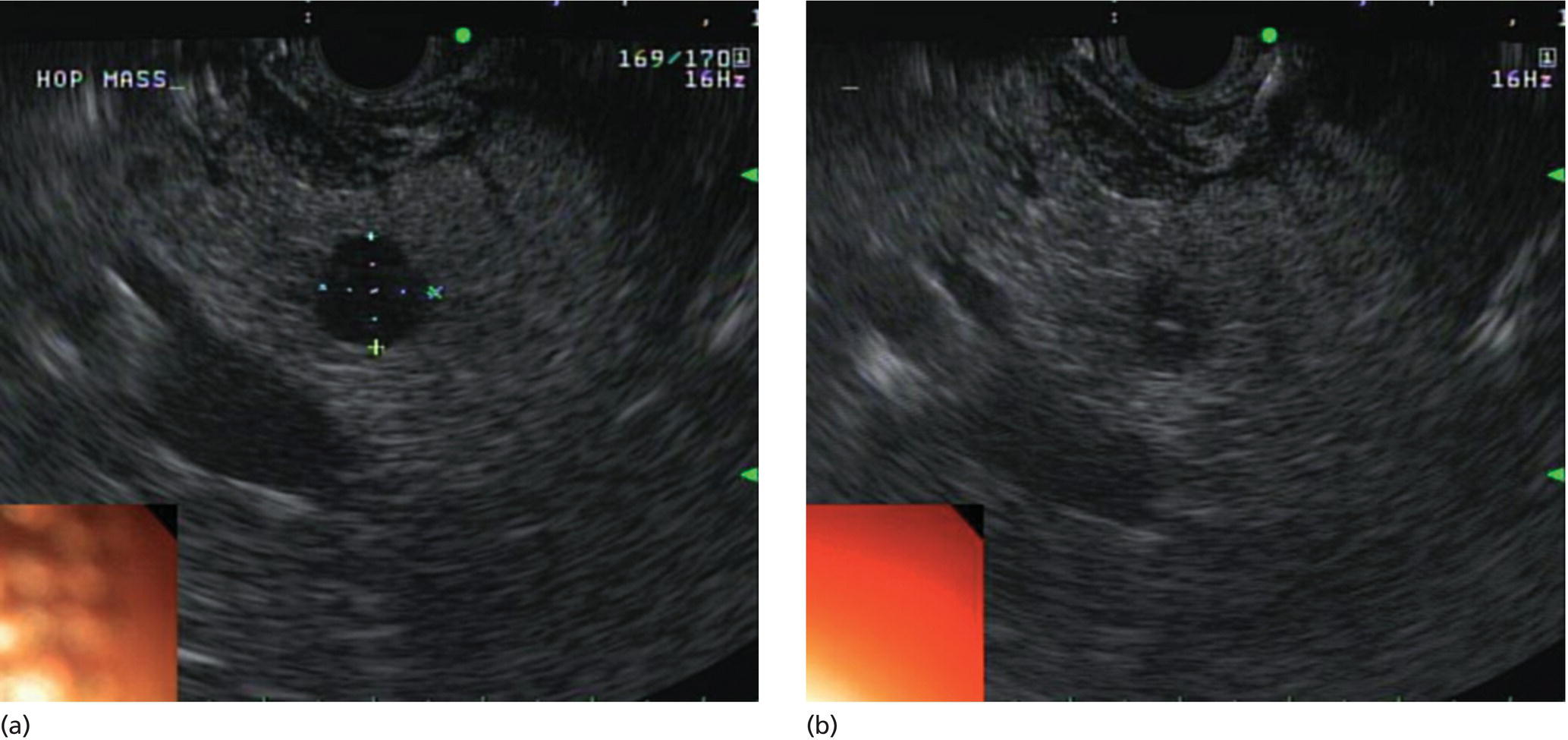

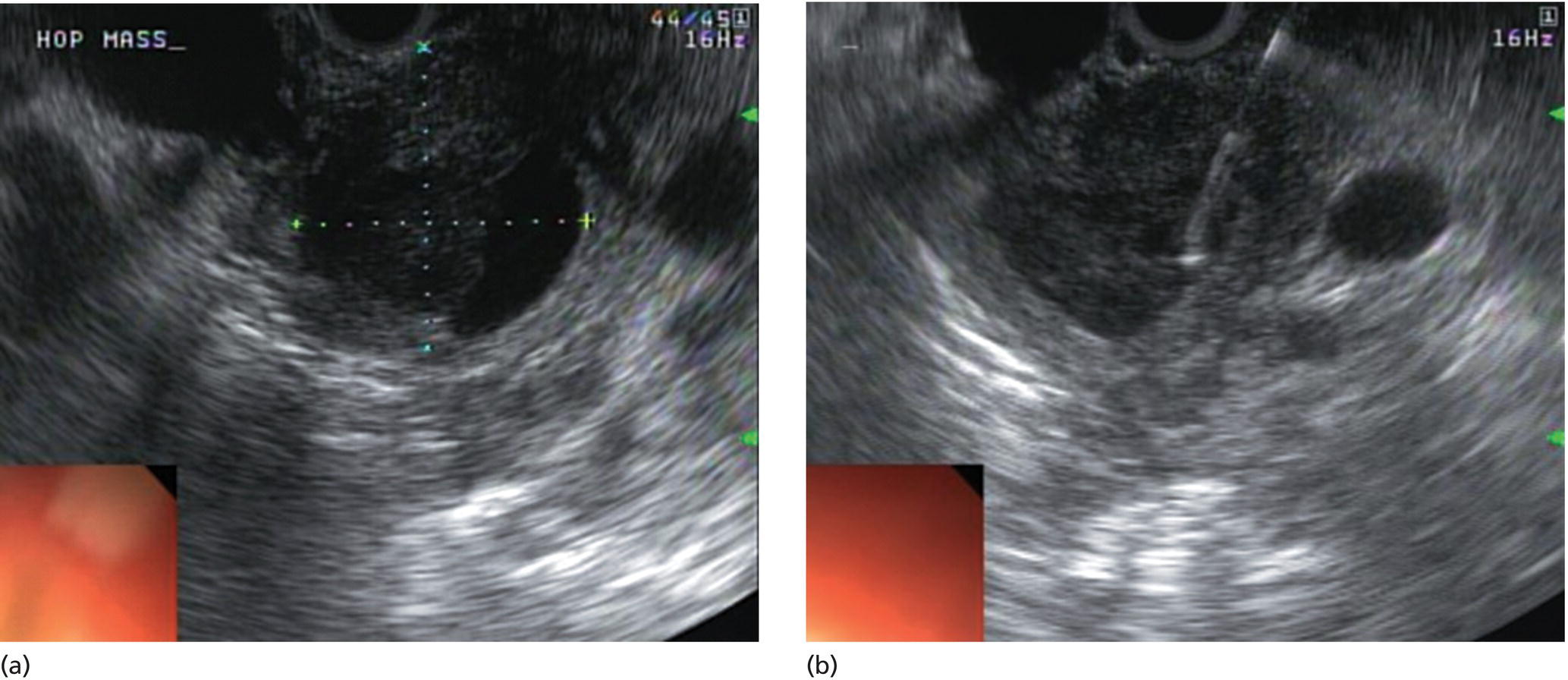

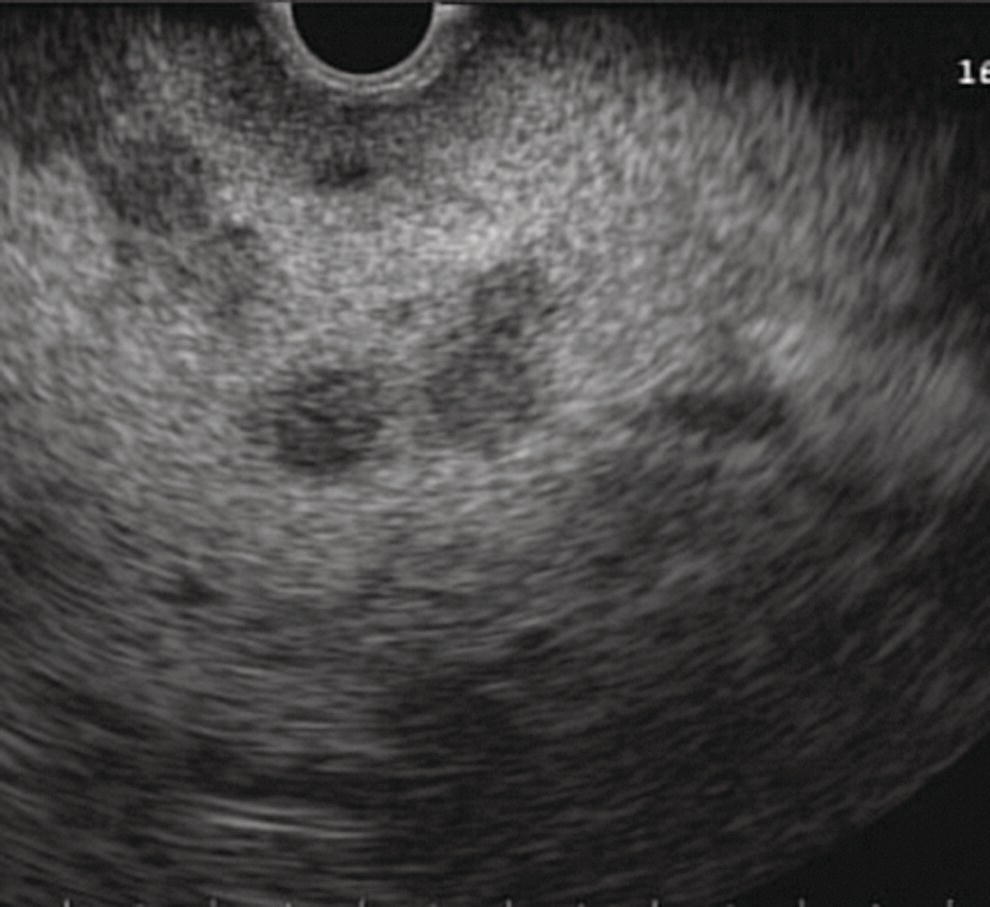

Yunseok Namn and Jonathan M. Buscaglia Stony Brook University Hospital, Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, USA Gastrointestinal specialists are frequently consulted for the diagnosis and management of solid lesions within the pancreas. These masses are often malignant and include pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, lymphoma, and metastatic disease presenting as a solid pancreatic lesion (e.g. renal cell carcinoma). Benign lesions include focal chronic pancreatitis and autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is the most sensitive imaging modality of the pancreas and remains pivotal for the evaluation of these solid masses. It allows for safe, minimally invasive characterization of pancreatic pathology with the ability for tissue acquisition in the form of ultrasound‐guided fine needle aspiration (FNA). The overall adverse event rate of EUS‐FNA is low, ranging between 1 and 2%. The risk of bleeding, which is usually self‐limited and without need for transfusions, is considered the most common complication. Pancreatitis is a rare complication and may occur more commonly after FNA of a cystic rather than a solid lesion. The chief advantage of EUS‐guided FNA is the ability to target small intrapancreatic masses and low‐grade malignancies that are often not accessible by computed tomography (CT) guidance. The decreased risk of malignant peritoneal contamination with EUS compared to CT‐guided FNA of pancreatic lesions is an added potential advantage. EUS‐FNA has an extremely low false‐positive rate with a positive predictive value of nearly 99%. Based on a large meta‐analysis, EUS‐FNA demonstrated an overall sensitivity of 85–91% and specificity of 94–98%. Various studies have shown a negative predictive value of 75%, with the majority of false‐negative cases resulting from sampling error. To optimize the diagnostic yield of EUS‐FNA of pancreatic lesions, preprocedural considerations should include reviewing the patient’s history, physical exam findings, and pertinent blood work. It is especially important to review all relevant cross‐sectional imaging such as a CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This provides the endosonographer with specific clues that may facilitate a more thorough and complete examination, such as the exact location of a lesion or its relationship with major vascular structures. Furthermore, knowledge of additional pathologic features such as hepatic metastases or abdominal ascites may be important if FNA results are non‐diagnostic, and they can frequently influence intraprocedural decision‐making. Figures 31.1–31.7 demonstrate typical examples of the sonographic appearance of masses in the pancreas during EUS evaluation. We often begin our examination with a radial echoendoscope and image the pancreas from the uncinate process to the tail of gland. This allows for a more thorough examination of the pancreas given the 270–360 degree imaging capability. It also facilitates a more complete evaluation of the pancreatic neck and tail, as well as the mediastinum. After the location of the mass is identified, we then introduce the curved linear array echoendoscope. Depending on the lesion location, FNA is performed transgastrically for lesions of the pancreatic genu, body, and tail. Transduodenal FNA is generally performed for lesions in the uncinate process and head of the pancreas. Transduodenal FNA is often more technically difficult due to the torque on the echoendoscope and the use of extreme upward tip deflection necessary for masses involving the uncinate process. Once the lesion is positioned favorably in a 5 o’clock to 7 o’clock position below the EUS probe, FNA is performed with the appropriate needle under constant EUS guidance. Multiple needles are available for FNA and include a 19‐gauge (G), 22‐G, and 25‐G needle. The choice of needle is based on the type of lesion targeted. For solid mass lesions, a 19‐G needle is generally discouraged due to the potential risk for bleeding, as well as the lack of data demonstrating a diagnostic advantage with larger‐caliber FNA needles. In general, we prefer to use the 25‐G needle because of its flexibility and thus ease of use in difficult positions with excessive torque on the echoendoscope to access the pancreatic head and uncinate region from the first or second portion of the duodenum. Figure 31.1 (a) Hypoechoic, irregular, 3‐cm adenocarcinoma in the head of pancreas. (b) Mass positioned in the 6 o’clock to 7 o’clock position during fine needle aspiration. Figure 31.2 (a) Small adenocarcinoma in the head of pancreas adjacent to the portal vein (PV) and a dilated pancreatic duct (PD). (b) Downstream dilation of the PD in the body of the pancreas. Figure 31.3 (a) Large 5‐cm adenocarcinoma in the tail of pancreas. (b) Mass positioned at the 6 o’clock position during fine needle aspiration with a 25‐gauge needle. Figure 31.4 (a) A 2‐cm mass in the head of pancreas with acoustic interference from a metal stent within the common bile duct. (b) Fine needle aspiration through the metal stent to sample tissue from the inferior portion of the mass. Figure 31.5 (a) Small 1‐cm hypoechoic neuroendocrine tumor in the head of pancreas. (b) Fine needle aspiration needle tip visible in the center of the mass. In straighter positions, such as within the stomach, we often use a 22‐G needle. Prior to FNA, the tip of the EUS probe is positioned in a fashion to minimize the distance between the lesion and the probe itself. This allows for greater precision when advancing the needle through the gastrointestinal tract and into the pancreas. Color Doppler is often used to exclude any intervening vessels just before FNA. When the FNA needle is in place inside the echoendoscope channel and appropriately fastened at the end of the scope, the stylet is pulled back approximately 1 cm to create a sharpened needle tip. Both dials controlling tip deflection on the echoendoscope are locked to ensure scope stability. Transgastric FNA can be challenging due to the thick gastric wall. To prevent tenting of the needle against the lumen, the gastric wall can first be suctioned to increase the angle at which the needle passes, followed by a quick spearing motion of the needle with sufficient force to penetrate the wall. This assures accurate entrance of the needle tip into the lesion. Once the FNA needle tip lies sufficiently within the center of the lesion, the stylet is pushed forward to purge any gastrointestinal contaminant obtained at the time of wall puncture. The stylet is then completely removed, and a 10‐ or 20‐ml syringe may be fastened to the operator end of the needle in order to apply suction to the needle’s lumen. This technique is often referred to as “dry suction” FNA. It is important to know that other techniques exist, such as the “wet suction” in which the needle lumen and syringe are filled with water before applying suction, as well as the “slow pull” technique in which no syringe is used and the stylet is simply pulled from the needle lumen as the operator is making several passes with the needle tip in the center of the lesion. The needle is then passed back and forth swiftly (multiple rapid thrusts) within the mass along separate linear planes while keeping the needle tip visible at all times to break up tissue for better cytologic yield. We recommend this “fanning” technique using the elevator and subtle tip deflections of the large echoendoscope dials to sample different areas as opposed advancing the needle back and forth through the same portion of the mass (Video 31.1). Figure 31.6 (a) Cystic neoplasm with malignant degeneration in the head of pancreas. (b) Fine needle aspiration targeting the solid components of the mass for higher diagnostic yield. Figure 31.7 Hepatic metastases visualized during EUS examination for a pancreas mass. In large solid masses, the center of the lesion is often soft and necrotic; therefore, the peripheral firm portions of the mass should be aspirated to maximize the cytologic yield. Prior to removal of the needle, suction should be turned off to prevent intestinal contamination. The needle is then removed completely from the echoendoscope channel, and an air‐filled syringe is used to flush the aspirated material onto glass slides. If clot is present within the needle, the stylet is inserted to push the material forward. A thin smear is then made and immediately rinsed with an alcohol fixative. For in‐room staining, a separate thin smear may be made and then air‐dried. Next, a Diff‐Quik™ stain is usually performed which allows for immediate evaluation by either the endosonographer or the cytotechnician. The number of passes with the FNA needle depends on the presence of rapid on‐site evaluation of cytology (ROSE), which is a valuable tool for optimizing diagnostic yield. The immediate evaluation of sample quality by the pathologist helps determine if the acquired sample was satisfactory for cytologic study and theoretically reduces the number of punctures. Some studies have shown that ROSE can improve the overall diagnostic yield of FNA by up to 10–15%. If ROSE is present, additional passes with the needle depend on the adequacy of the specimen delivered to and assessed by the cytotechnician. When ROSE is not available, we generally perform three separate passes with the needle, and then await a future and final cytopathologic interpretation. If para‐tumor or celiac axis lymph nodes are noted, FNA with a separate needle can be performed in a similar fashion. This may be especially important in making an accurate diagnosis for a necrotic mass lesion in which adequate tissue acquisition is often difficult. As an adjunctive diagnostic tool, contrast‐enhanced EUS can be used to assess the vascularization and perfusion patterns of pancreatic masses. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma has a distinct hypovascular appearance while other pancreatic processes, such as neuroendocrine tumors and chronic/autoimmune pancreatitis, have either a hypervascular or isovascular appearance. EUS elastography is another technique that can help distinguish pancreatic cancer from other inflammatory masses based on tumor elasticity. Fine needle aspiration is an important tool in the diagnosis and management of pancreatic masses. Studies have shown the overall accuracy of EUS‐FNA ranges between 71 and 94% in this setting. It is important to review all pertinent clinical data (especially cross‐sectional imaging) prior to performing endoscopy to optimize the diagnostic yield. The choice of the needle may depend on the location and size of the lesion. Once the lesion is targeted and placed in optimal position, FNA is performed under total EUS guidance while visualizing the needle tip at all times. Factors that may increase the diagnostic yield of FNA include sampling the lesion in multiple planes through the “fanning” technique, targeting the firmer peripheral margins of the necrotic mass, and arranging for rapid on‐site evaluation of cytology (Box 31.1). Contrast‐enhanced EUS and EUS elastography can be useful adjunctive techniques to help characterize, differentiate, and stage focal pancreatic masses.

31

How to do Pancreatic Mass FNA

Introduction

The technique

Final considerations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree