div class=”ChapterContextInformation”>

2. Current Imaging Approaches and Challenges in the Assessment of the Intracranial Vasculature

Keywords

Catheter angiographyCT angiographyMR angiographyLuminal imagingIntracranial vasculopathyVascular diseaseStrokeLuminal Imaging Basics

Luminal imaging is a vascular imaging technique that evaluates the caliber of the intracranial vasculature. In some instances, these techniques can also provide information regarding the hemodynamics through vessels of interest. Conclusions regarding underlying vessel pathophysiology are ultimately drawn from the observed luminal irregularity and alterations in flow. Catheter digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is typically performed in a dedicated biplane neuroangiography suite. Before diagnostic images can be taken, intra-arterial access must be first acquired and a vessel(s) of interest must be selectively catheterized. Images are then acquired with high temporal resolution as a bolus of contrast flows through the vasculature of interest. CTA is a noninvasive luminal imaging modality that requires intravenous administration of iodinated contrast prior to image acquisition. Modern CT scanners rely on a multi-detector array for photon detection and image acquisition. Multiplanar reformats are subsequently derived from source data with high spatial resolution [1]. MRA techniques allow for the assessment of the vessel caliber and, in some instances, flow characteristics through intracranial vasculature. MRA acquisitions can be performed with or without intravenous contrast. Contrast-enhanced (CE) MRA relies upon the T1 shortening effects of paramagnetic contrast media for luminal visualization [2]. Non-CE-MRA relies upon the intrinsic signal characteristics of flowing blood for luminal visualization. Noncontrast techniques specific to neurovascular imaging include time-of-flight (TOF), phase-contrast (PC), and arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRA.

Technical Aspects of Luminal Imaging

Conventional CTA

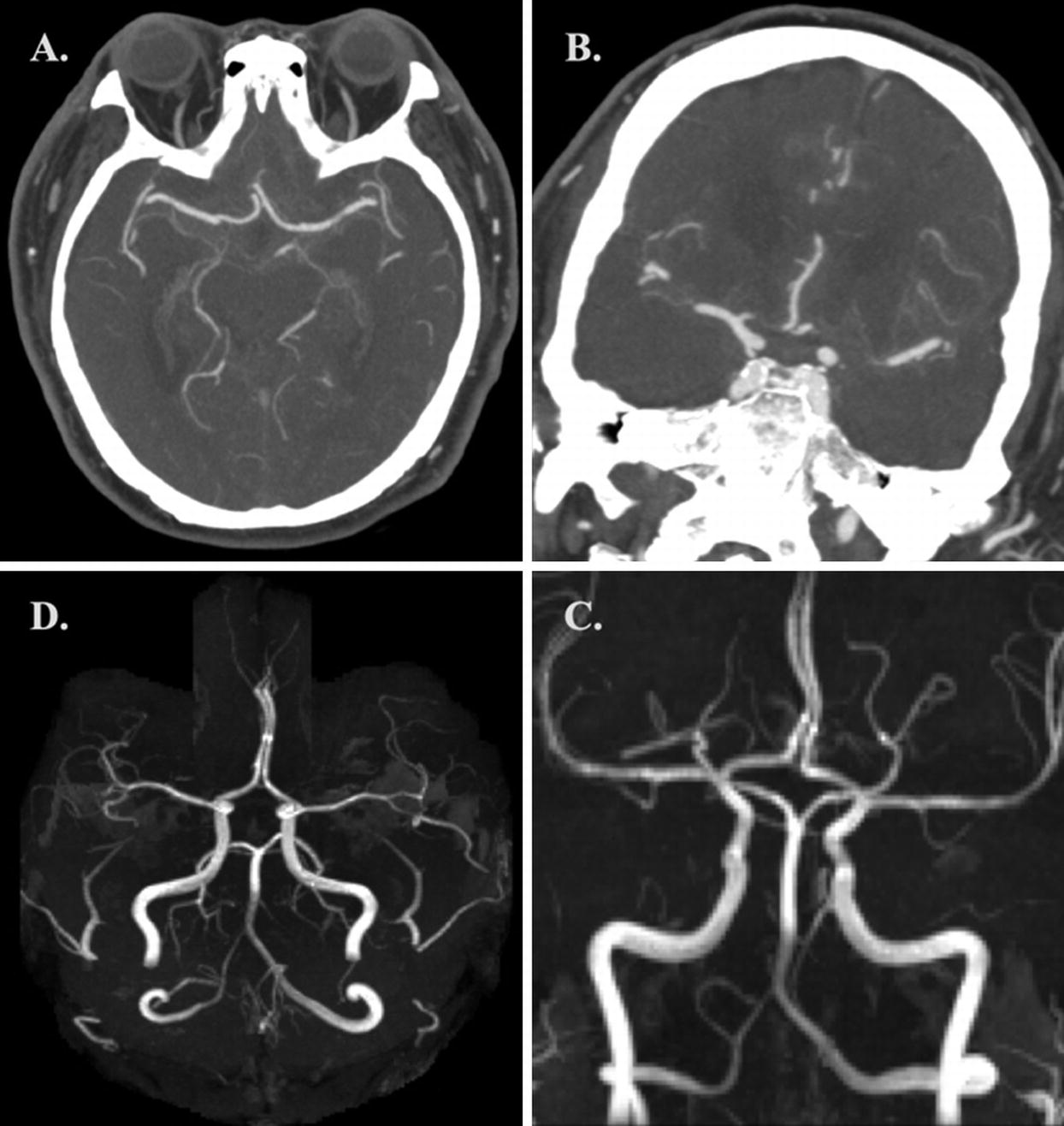

(a, b) Axial and coronal CTA MIP images demonstrating normal intracranial vasculature. (c, d) Coronal and axial 3D-TOF-MRA MIP images demonstrating normal intracranial vasculature

Catheter Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA)

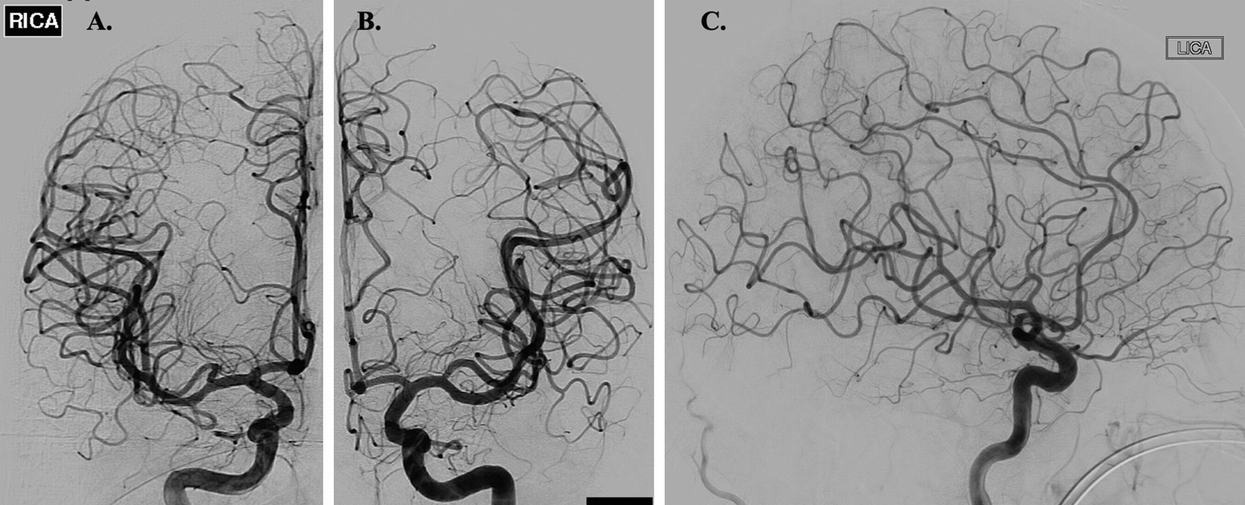

(a, b) Frontal DSA images of the right and left ICA, respectively, illustrating normal intracranial vasculature. (c) Lateral DSA image of the left ICA again demonstrating normal intracranial vasculature

Dual-Energy CTA (DE-CTA)

Dual-energy CT (DE-CT) takes advantage of differences in x-ray attenuation by target materials. These differences in attenuation are dependent upon the energy of the incident photons [7]. The attenuation of materials with a high atomic number is greater with lower energy incident photons than with higher energy incident photons [7]. Similarly, the attenuation of blood vessels is more conspicuous when a low tube voltage is used [7, 8]. When an object of unknown composition is imaged with two distinct energy spectra, materials within the object can be differentiated by comparing the change in differential x-ray attenuation to the x-ray attenuation of known reference materials [7].

There are three DE-CT systems currently available. These include dual-source dual-energy CT (DSDE CT), single-source dual-energy CT (SSDE CT) with fast kilovolt-peak switching, and single-source dual-layer detector CT systems [9, 10]. DSDE CT uses two x-ray tubes that operate at different voltages (80 kVp and 140 kVp) positioned at 90° from each other [10]. In this system, spectral filtration can be independently optimized for each tube-detector pair, thus improving image quality. Due to differences in tube positioning relative to the target, acquisition of the two different datasets occurs at slightly different times, limiting the temporal registration of the DSDE CT images. Because both tubes are simultaneously energized, scattered radiation from one tube may be detected by the detector panel of the other tube (and vice versa), leading to degradation in spectral separation. Implementation of an appropriate scatter-correction algorithm can help correct for this phenomenon [10].

SSDE CT with fast kilovolt-peak switching relies on fast switching between 80 and 140 kVp performed every 250 microseconds during a single projection for spectral separation. This results in the acquisition of 1000 high-energy and 1000 low-energy projections during a single 360° gantry rotation at a full field of view of 50 cm. Unlike DSDE CT, SSDE CT with fast kilovolt-peak switching produces well-preserved spectral separation, and temporal misregistration of the spectral datasets rarely occurs. SSDE CT with a dual-layer energy detector relies on spectral separation at the level of the detector. A layered detector separates low-energy photons collected by the innermost detector layer from high-energy photons collected by the outermost detector layer from a single x-ray source [10].

Acquisition of low-energy monochromatic images with DE-CT allows for improved vessel contrast on CTA. These low-energy monochromatic images prove particularly helpful in delineating small, peripheral vessels [10]. Although the use of a low tube voltage with a traditional single-energy CT scan can produce similar effects, this comes at the cost of increased image noise which is not encountered with DE-CT. Additionally, acquisition of low-energy monochromatic images allows for the use of reduced iodinated contrast volumes while still preserving image quality [10]. This may prove helpful when imaging patients with underlying renal insufficiency in whom there is a clinical desire to minimize iodinated contrast exposure.

DE-CTA allows for the correction of beam-hardening artifact. Beam hardening arises when low-energy photons within a polychromatic x-ray beam are preferentially absorbed as they pass through a target [10]. This can result in streak on the reconstructed imaging and is frequently appreciated near the skull base and within the posterior cranial fossa. DE-CT corrects beam-hardening errors in the iodine- and water-based projection data, resulting in a reduction in beam-hardening artifacts and improved image quality [10].

Metallic implants produce significant streak artifact when imaged on a single-energy CT scanner. Monochromatic images obtained at higher energies with DE-CTA have increased penetration which reduces blooming and metallic streak artifacts [9, 10]. Image data collected at lower energies can then be used to correct for the decreased vessel contrast that occurs at these higher incident photon energies. The reconstructed image will display reduced metallic streak artifact with preserved vascular contrast. This technique proves particularly useful in evaluating vessel lumen patency following intraluminal stent placement. DE-CTA also allows for the subtraction of metallic artifacts, such as intracranial coil masses, from the reconstructed CTA images. This is accomplished through the subtraction of monochromatic images between the two energy levels obtained from the same datasets. In doing so, complete removal of objects with CT attenuation values that reach an upper threshold at both energy levels is achieved. Delineation of the parent vessel remains well-preserved on the subtracted monochromatic images [10]. This same technique can be applied to arterial wall calcifications and adjacent osseous structures, allowing for improved vessel lumen visualization [10–13].

Unlike conventional CTA, DE-CTA allows for reconstruction of virtual noncontrast images (VNC) from DE-CTA source data. Material subtraction images allow for the measurement of CT attenuation values on monochromatic images at 70 keV, which is equal to images acquired on a single-energy CT scanner at 120 kVp. VNC images allow for a reduction in overall radiation exposure, as separate scans acquired before and after contrast administration are no longer necessary [10].

4D-CTA/Timing-Invariant CTA (TI-CTA)

Four-dimensional CTA (4D-CTA), also referred to as timing-invariant CTA (TI-CTA), combines the noninvasive nature of conventional CTA with the dynamic imaging capabilities of catheter DSA [14]. 4D-CTA provides information regarding both the magnitude and directionality of flow through vessels of interest. It also details the angioarchitecture of the vasculature in question [14].

Like catheter DSA, a contrast bolus is delivered intravascularly and then imaged in real-time as it flows through the vasculature of interest. There are three distinct image acquisition techniques for performing 4D-CTA. These include volume mode, toggling-table mode, and shuttle mode scanning. The width of the CT detector ultimately determines which acquisition mode can be used to ensure adequate brain coverage [15].

Volume mode acquisitions are the most versatile, allowing for complete or partial coverage of the intracranial circulation. CTA data can be acquired either continuously throughout a pre-specified time period or discontinuously at either preset fixed or variable time intervals. During discontinuous volume mode acquisitions, the time intervals typically range from 1 to 4 seconds [15]. The datasets obtained at each of these time intervals are then overlaid to produce the final dynamic images [14]. True 4D datasets from continuous volume mode acquisitions can then be retrospectively reconstructed at any time interval. In general, the temporal resolution for this technique is on the order of 0.275–0.5 seconds [15]. Continuous scanning is only possible with volume mode acquisitions. Patients with high-flow vascular malformations benefit from the high temporal resolution of continuous acquisitions. When assessing collateral flow following arterial occlusion, a lower temporal resolution may be used, making the other acquisition techniques viable alternatives [15, 16].

4D-CTA images can be reconstructed from CT perfusion (CTP) datasets. In CTP, multiple CT datasets are acquired at different time intervals following the injection of intravenous contrast. Because 4D-CTA images can be reconstructed from CTP datasets, CTA imaging performed in addition to CTP imaging is not necessary, saving both time and radiation exposure [17]. By reconstructing 4D-CTA from CTP data, it is possible to evaluate both the angioarchitecture of the vasculature in question and the associated cerebral perfusion. The combination of these imaging techniques allows for the comprehensive assessment of the cerebral collateral vessels and the parenchymal perfusion that they supply [17–22].

Maximum intensity projections (MIPs) constructed from the 4D-CTA datasets provide an accurate overview of the vasculature of interest. Bone subtraction post-processing techniques can be used to generate DSA-like images that can be viewed as a temporal sequence that shows the arterial inflow and venous washout of contrast. By filtering the data in the temporal domain, spatial resolution remains intact, while noise is reduced, allowing for TI-CTA reconstructions of the vascular tree [15].

Time-of-Flight MRA (TOF-MRA)

TOF-MRA relies on suppression of background signal by slice-selective gradient echo excitation pulses [2, 24, 33]. In the selected slice or volume, static tissue experiences a rapid series of radiofrequency pulses that cause the tissue to lose most of its T1 signal. Inflowing blood, however, has not experienced these radiofrequency pulses and enters the slice or volume fully magnetized demonstrating a stronger T1 signal relative to the saturated background [24]. Saturation radiofrequency pulses are applied downstream of the slice or slab to suppress inflowing venous spins. Arterial contrast depends upon a combination of the T1 signal of both the arterial blood and background tissue, the radiofrequency pulse spacing and flip angle of the gradient echo sequence, and the velocity of the inflowing blood [33]. TOF-MRA can be acquired in 2D or 3D formats, with 3D TOF-MRA being more suitable for imaging the intracranial arteries [2] (Fig. 2.1c, d). Three-dimensional acquisitions allow for isotropic voxels with submillimeter slice resolution [33]. Three-dimensional TOF-MRA is associated with longer image acquisition times, however, as well as increased susceptibility to flow dephasing artifacts resulting in loss of flow-related signal [2].

Multiple overlapping thin slab acquisition (MOTSA) is a hybrid of 2D TOF-MRA and single-slab 3D TOF-MRA that produces isotropic voxels with high spatial resolution and allows for larger anatomic areas of coverage [2, 34]. Overlapping subvolumes are sequentially acquired, before then being fused with other subvolumes to create a complete 3D volume [2].

First-pass Contrast-Enhanced MRA (CE-MRA)

First-pass CE-MRA images are commonly acquired using a T1W 3D gradient echo sequence [23, 24]. Artery visualization relies on the T1 shortening effects of intravenously delivered paramagnetic contrast agents, which makes the arteries of interest appear bright on imaging [2]. Suppression of background signal is achieved by the application of a 3D radiofrequency spoiled gradient sequence [2, 24].

First-pass CE-MRA depends upon appropriate contrast bolus concentration and timing to optimize vessel visualization. The volume of contrast required is dependent upon the magnetic field strength used, with lower concentrations and smaller volumes of contrast required when imaging is performed at higher magnetic field strengths. The contrast injection rate determines the arrival time of contrast at the vascular bed of interest. A fast injection ensures a tight bolus of contrast arriving over a short period; however, if the rate of infusion is too rapid, infusion-related artifacts can result. Optimal arterial visualization can generally be achieved using a double dose of contrast (0.2 mmol/kg) infused over a slower rate (2 mL/s) [2].

Standard extracellular contrast media are commonly used for first-pass CE-MRA and provide strong and selective enhancement of the vessels of interest [25, 26]. During the steady state, however, rapid contrast-agent extravasation occurs, resulting in decreases in the vessel contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) and increased background signal within the surrounding soft tissues [25]. Consequently, these agents have a relative short distribution phase half-life of approximately 100 seconds [18], limiting the time available for image acquisition. Agents such as Gd-DTPA (Magnevist) and Gd-BOPTA (MultiHance) fall into this category.

Unlike standard extracellular contrast media, blood pool agents (BPA) demonstrate a prolonged intravascular distribution, allowing for strong and prolonged intravascular enhancement [25]. BPA provide an increased time frame for image acquisition (up to 60 minutes) and make steady-state MRA with high spatial resolution possible [27, 28]. BPA demonstrate significantly higher signal intensity in pre-stenotic and post-stenotic vessel segments [27], and MRA performed with BPA has demonstrated superior image quality of the intracranial vasculature compared to standard extracellular contrast agents [18].

These agents can be divided into three broad categories which include ultrasmall supraparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) particles , paramagnetic gadolinium-based macromolecules, and gadolinium-based small molecules with strong reversible protein binding. Of these three classes, USPIO particles and gadolinium-based small molecules with strong reversible protein binding prove to be the most clinically promising. USPIO particles demonstrate strong T1 and T2 shortening effects and are retained within the intravascular space for prolonged periods of time. On T1W imaging, these particles appear bright. Sequences with short echo times are necessary to minimize confounding susceptibility artifacts [25]. Examples of USPIO particles include ferumoxtran-10 (Combidex, Sinerem, Guerbet, France), ferumoxytol (Advanced Magnetics, USA), and SHU-555C (Supravist) (Bremerich 2007). These agents have not yet received FDA approval for clinical use. Although paramagnetic gadolinium-based small molecule agents, such as gadofosveset trisodium (Vasovist/Ablavar), have received FDA approval for use in humans, they are no longer made commercially available by their manufacturers.

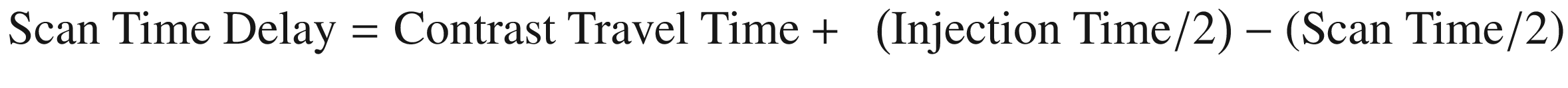

First-pass CE-MRA requires the appropriate timing between contrast bolus infusion and image acquisition. The scan time delay between contrast agent infusion and the start of imaging acquisition can be approximated using the following formula [2]:

This formula does not take into account reduced cardiac output, high-grade arterial stenoses, or abnormal shunt vascularity [2]. A contrast test bolus of 1–2 mL that is injected at the same rate as the actual injection can be used to determine the contrast travel time [2]. From this, the appropriate scan delay can be deduced. Automated bolus detection represents an alternative method for coordinating contrast bolus delivery and image acquisition [23]. This technique involves monitoring a vessel of interest for the arrival of contrast. Once an adequate contrast volume is within the vessel, image acquisition is initiated [2].

Optimization of image acquisition parameters is essential to acquiring high-quality angiographic images. Repetition time (TR) should be kept as short as possible (<4 ms) without increasing the bandwidth [2, 24]. By decreasing TR, it is possible to perform multiphase imaging or increase image spatial resolution. As TR is shortened, however, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) subsequently decreases. This can be compensated for by increasing the rate of contrast infusion [2, 24]. Like TR, echo time (TE) should also be kept as short as possible (<2 ms). A shortened TE decreases proton dephasing which in turn reduces the loss of intravascular signal [2]. This can also decrease SNR by widening the readout bandwidth. TR, TE, and SNR are each affected by changes in the readout bandwidth, with a high readout bandwidth allowing for shorter TR and TE at the expense of SNR. A readout bandwidth of 32–64 kHz is generally sufficient for CE-MRA. The flip angle typically ranges from 20 to 60° in the case of CE-MRA with most image acquisitions utilizing a flip angle between 30 and 45° [2]. Low flip angles are better suited for low contrast doses, slow injection rates, and very low TR, whereas high flip angles are better for high contrast doses and imaging with higher TR.

Increasing the magnetic field strength increases SNR which can be used to increase spatial resolution, decrease image acquisition time, or reduce contrast dose [2, 24]. A 3T field strength causes a T1 prolongation of tissue. Subsequently nonvascular tissues with longer T1 relaxivities are more readily suppressed with 3T scanners [24]. Increased magnetic field strength also increases the specific absorption rate (SAR) and generates higher field inhomogeneities when compared to 1.5T. Increased SAR limits the maximum flip angle that can be used, thereby limiting the increase in SNR. Despite these technical limitations, the net gain in signal remains higher at 3T when compared to 1.5T [2].

Time-Resolved Contrast-Enhanced MRA (TR-CE-MRA)

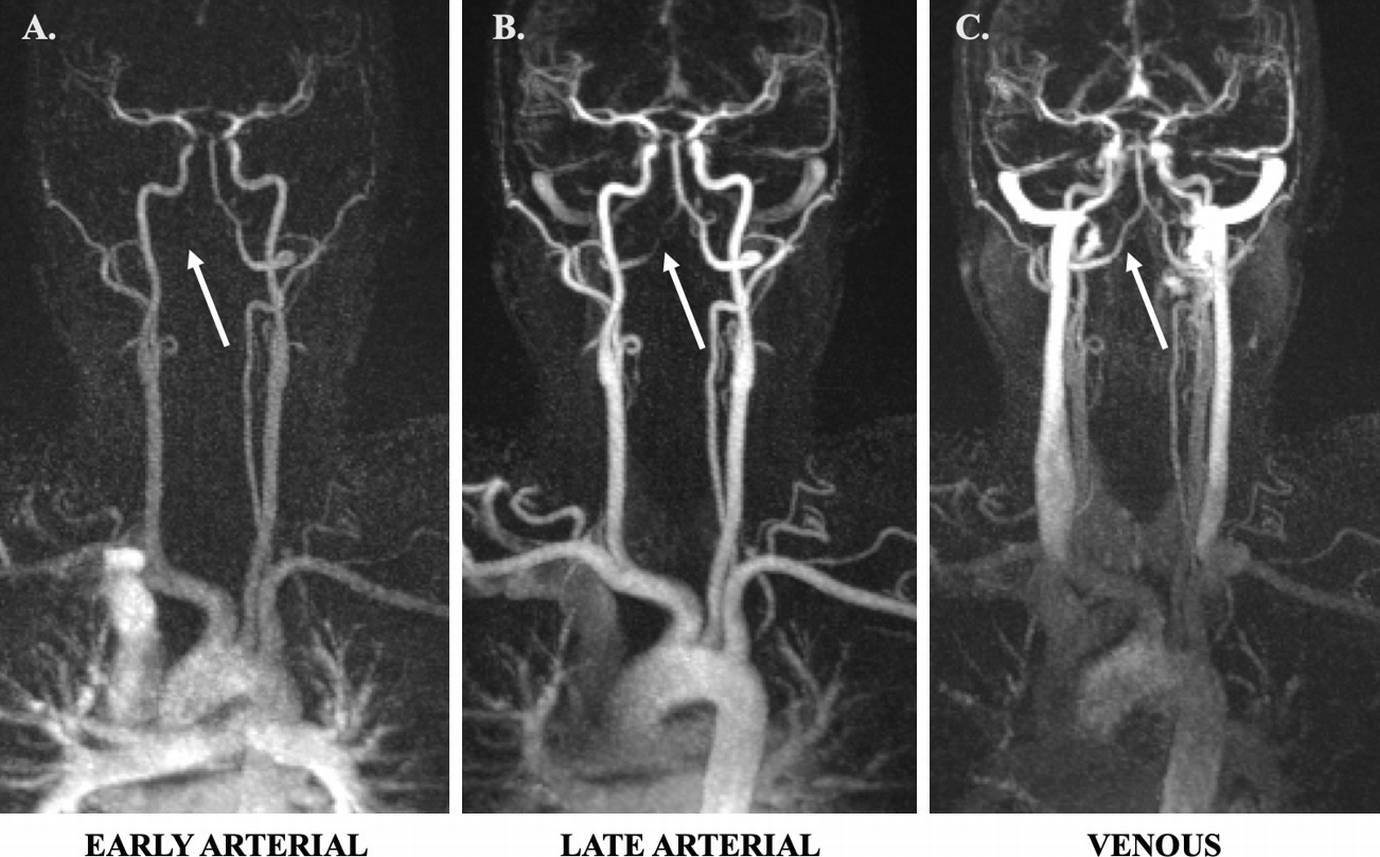

(a) Coronal TR-TWIST-MRA acquired during the early arterial phase shows opacification of the pulmonary vasculature, aorta, and the major aortic branch vessels. Although the carotid arteries and left vertebral artery are well visualized, the right vertebral artery is not opacified (arrow). (b) A late arterial phase image shows delayed partial opacification of the right vertebral artery (arrow). (c) Venous phase image shows increased delayed opacification of the right vertebral artery (arrow). This patient was found to have a right vertebral artery dissection with impaired flow through the vessel. Non-time-resolved MRA techniques could have led to an erroneous diagnosis of vertebral artery occlusion

Keyhole imaging generates a series of images by combining rapidly acquired temporal samples of the central k-space region before performing a single sampling of the outer regions of k-space at the end of the scan [2, 31]. Although this technique provides some sense of the flow dynamics through vessels of interest, high spatial frequency venous signals appear even in the early arterial frames due to late high spatial frequency sampling [31]. CENTRA imaging relies on randomly segmented k-space ordering in which a central sphere of k-space is randomly sampled during the full arterial window. Acquisition of data can extend beyond the time of passage of the contrast bolus through the arteries so that high spatial resolution of a large field of view is achieved [2].

TRICKS imaging samples the center of k-space more frequently than the periphery, and time frames are formed by temporal interpolation [2, 31]. K-space is subdivided into fixed portions, and a part of the peripheral k-space is updated for every keyhole dynamic. Additionally, a rectangular keyhole is used to acquire full lengths of k-space lines [24]. The TRICKS technique then attempts to estimate missing k-space data by linear interpolation of values from shared data across time frames [30]. TRICKS increases the frame rate of a 3D multiphase examination by a factor of 3–4 [2]. This technique offers a significant improvement over the keyhole method because of the ongoing updating of high spatial frequency information. This technique and subsequent derivate methods are the most prevalent commercially available methods for TR-CE-MRA. Although frames may be updated every few seconds, the data used to form each frame covers a substantial time interval of 10 seconds or more due to the temporal interpolation that is required [31].

Multiple variations of the TRICKS technique exist, each with its own unique name. The main differences between these techniques are the size of the central k-space portion that is sampled and how it is combined with k-space periphery data [24]. Like TRICKS, the TREAT technique uses a rectangular keyhole to acquire full lengths of k-space lines with alternating lines of k-space being sampled with each iteration [32]. The TWIST technique alternates between sampling central and peripheral k-space using a spiral, pseudostochastic trajectory. This trajectory is based on the radial distance from the center of k-space and partially updates the k-space periphery [24, 32]. 4D-TRAK combines the CENTRA technique with sensitivity encoding (SENSE), partial Fourier, and keyhole techniques [2]. A central keyhole ellipsoid of k-space is acquired at each successive dynamic time point, and the periphery of k-space is acquired at the last dynamic time point. The k-space periphery acquired at the end of the scan is then used to reconstruct all of the previous dynamics where only the central keyhole was acquired, ultimately optimizing the speed with which contrast enhancement is captured [24]. 4D-TRAK allows for more than 60-times accelerated MRA with high spatial resolution [2, 24]. Temporal resolutions of 1.6–3 seconds can be achieved within the intracranial vasculature [2]. The temporal performance of dynamic high-resolution 3D TR-CE-MRA is faster than what can be achieved by conventional first-pass CE- or non-CE-MRA techniques [2].

Phase-Contrast MRA (PC-MRA)

PC-MRA generates image contrast by exploiting inherent differences in transverse magnetization that occurs between stationary and moving tissues, resulting in phase shifts [2]. PC-MRA uses a flow-encoding gradient along multiple planes to visualize flow [2, 24]. Gradients are turned on in one direction at a time for a pre-specified time interval before then being switched in orientation for the same amount of time. The first gradient dephases spins, while the second gradient rephases spins that are stationary. After application of this bipolar gradient, stationary spins associated with background tissue will have a zero phase shift, whereas spins associated with the flowing intravascular blood pool will accumulate a net phase shift that can then be visualized [24, 33]. This phase shift is proportional to the flow velocities within the imaged vessels [2] with higher flow velocities accumulating more phase shift. Velocity-induced phase shift can subsequently be quantified [2, 35].

PC-MRA requires preselection of a velocity-encoding factor (Venc) based on whether faster moving arterial blood or slower moving venous blood will be imaged [2]. Appropriate Venc selection is critical to image quality. If the Venc is too low, velocity aliasing occurs, whereas if the Venc is too high, vascular CNR will be too low due to decreased sensitivity to slow flow near the edge of the vessel lumen [2, 24, 33]. A reference image is acquired in addition to the velocity-encoded scan. The reference image can then be subtracted from the flow-sensitive images to remove phase errors unrelated to flow. Because phase shift is proportional to flow velocity, an image can be generated where pixel intensity directly relates to flow velocity [24].

Arterial Spin Labeling MRA (ASL-MRA)

ASL-MRA labels flowing spins within the blood pool for image generation. ASL-MRA requires that two image sets are acquired and later subtracted for final image generation. These two image sets differ only in the magnetization of inflowing arterial spins. Pseudocontinuous labeling techniques can also be utilized. In this variant, a stream of radiofrequency energy is applied to a thin (~1 cm thick) labeling plane through which intravascular arterial spins flow before traveling downstream into the vasculature of interest. Pseudocontinuous ASL (pCASL) improves the SNR of vessels near the labeling plane. ASL-MRA allows for high arterial contrast and complete elimination of background signal. The use of extended, multiphase readouts can provide time-resolved ASL data as illustrated by triggered angiography noncontrast-enhanced (TRANCE) MRA (Philips Healthcare; Best, Netherlands) [33].

Clinical Considerations for Luminal Imaging

Catheter DSA

Catheter DSA has superior spatial and temporal resolution when compared to noninvasive, cross-sectional luminal imaging modalities, making it well-suited for the detection of small cerebrovascular lesions, such as blister aneurysms of the supraclinoid ICA, small AVMs, and small dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF). DSA has been shown to better characterize geometric features of aneurysms, including the width and conformation of the aneurysm neck, when compared to CTA and MRA [36]. Traditionally, DSA has been used to assess changes in the intracranial vasculature following open surgery, endovascular intervention, or radiation therapy. Because intra-arterial access is required to perform DSA, examinations can be easily converted into therapeutic endovascular procedures, such as endovascular aneurysm coiling or parent artery reconstruction, should the need arise.

Catheter angiography is an invasive procedure with associated iatrogenic risks. The most serious of these complications is catheter-associated embolic phenomena capable of producing transient or permanent focal neurological deficits. The risk of transient focal neurological deficits following cerebral angiography is estimated to be 0.9%, whereas the risk of permanent neurological deficit is lower, estimated to be 0.5% [6, 37–40]. Arterial wall dissection is also possible. Puncture site complications include perivascular hematoma, arterial pseudoaneurysm formation, arteriovenous fistula formation, and vessel occlusion. The risk of clinically significant perivascular hematoma requiring either surgical evacuation or blood transfusion is approximately 0.2%. The risk of arterial injury or arterial occlusion requiring surgical thrombectomy or thrombolysis is approximately 0.2% [41].

Catheter angiography exposes both patients and operators to radiation. The dose of radiation that one receives increases with increasing frame rate of image acquisition. An individual’s cancer risk is proportional to increases in radiation exposure [6, 42, 43]. Unlike noninvasive luminal imaging, catheter angiography requires the coordination and participation of multiple other clinical providers, including dedicated neurointerventionalists and their associated support staff. This makes catheter angiography a time- and resource-intensive endeavor relative to CTA and MRA.

2D DSA projections can limit detection of subtle vascular lesions due to vessel overlap. In these instances, dedicated 3D rotational angiography (3DRA) acquisitions are helpful in further evaluating a region of interest. Despite catheter angiography’s superb spatial and temporal resolution, it does not allow for direct visualization of soft tissues, including the vessel wall. Clinically relevant information regarding vessel wall characteristics such as abnormal wall thickening, atherosclerotic plaque burden and composition, vessel wall inflammation, and the presence of intramural hematoma or intraplaque hemorrhage remain largely unknown when catheter angiography is used to assess the intracranial vasculature. In the case of ICAD, catheter DSA can significantly underestimate plaque burden as plaque remodeling often occurs in an outward fashion early in the disease process without appreciable luminal stenosis.

Conventional CTA

The combination of high spatial resolution, short image acquisition time, and the noninvasive nature of conventional CTA makes it an ideal screening examination, particularly in critically ill individuals or in the emergency department setting where efficient patient triage and throughput is essential to overall departmental function. As such, a patient’s clinical stability is less of a concern when it comes to CTA image acquisition. Critically ill patients are often able to complete both noncontrast head CT and CTA image acquisitions without issue.

Compared to DSA, there is little short-term risk to patients in performing CTA. Like DSA, iodinated contrast is utilized in CTA imaging protocols. While rare, allergic reactions occur in approximately 0.2–0.7% of patients exposed to intravenous low-osmolar iodinated contrast media. The majority of these reactions are nonlife-threatening [44]. Like contrast-induced allergic reactions, contrast-induced nephropathy is also considered a rare clinical entity that is most likely to occur in patients with poor baseline renal function, though this topic is controversial [45–48] and some question the existence of post-contrast acute kidney injury. Nonetheless, caution should still be exercised in patients with ordered CTA exams who have severely compromised renal function but continue to produce urine [45, 48–50].

CTA is of limited utility in the evaluation of intracranial vascular lesions following open surgical clipping, coil embolization, or endovascular flow diversion. This is due to significant metallic streak artifact generated by these implanted materials. CT imaging in general has difficulty evaluating the posterior cranial fossa and skull base secondary to beam-hardening artifact and photon starvation caused by the dense surrounding bone.

CTA has difficulty detecting small (<3 mm) aneurysms, including blister aneurysms, small bifurcation aneurysms, perforator artery aneurysms, dissecting aneurysms, and peripheral mycotic and myxomatous aneurysms [38]. CTA, with the exception of time-resolved or multiphase CTA, only provides a single time point of imaging. This limits its ability to thoroughly evaluate vascular lesions that demonstrate shunting phenomena such as intracranial AVMs and dAVFs. Additionally, CTA provides limited information about pathological processes affecting the intracranial arterial walls. While findings such as eccentric narrowing of the vessel lumen may suggest ICAD, these findings are not accurate for vasculopathy differentiation.

DE-CTA

Relative to conventional CTA, DE-CTA can be used to improve vessel contrast, particularly as it relates to small and peripheral blood vessels. This proves particularly useful in the evaluation of the intracranial vasculature. The distinct high- and low-energy spectra generated by DE-CTA can be used to reduce beam-hardening artifact at the skull base and within the posterior cranial fossa. These spectra can also be used to minimize metallic streak artifact from objects such as aneurysm clips, endovascular coil masses, or endovascular flow diverters. DE-CTA can be used to reliably assess vessel patency following endovascular stent placement as well as to evaluate for residual aneurysm sacs following microsurgical clipping. This imaging modality is highly sensitive to parent vessel compromise and residual aneurysm sac formation following the placement of multiple aneurysm clips [9]. DE-CTA can produce VNC images from DE-CTA datasets which are helpful in assessing for intracranial hemorrhage and differentiating hemorrhage from iodinated contrast [10], potentially allowing for better prediction of hematoma expansion. Unlike conventional CTA where patients must be scanned before and after contrast delivery, DE-CTA requires only one scan from which VNC images can be reconstructed. This ultimately reduces patient radiation exposure.

Despite its many advantages, DE-CTA has several pertinent shortcomings. First, DE-CTA exposes patients to ionizing radiation. However, the total radiation dose for DE-CTA is estimated to be equivalent to or reduced relative to standard CTA imaging [7, 10, 12]. Although VNC images can be generated from DE-CTA datasets, they have more noise than conventionally acquired noncontrast head CT images. This image noise, however, does not appear to adversely affect radiologists’ abilities to identify acute intracranial hemorrhage [22].

4D-CTA/TI-CTA

The clinical value of 4D-CTA comes from its ability to provide both vascular structural information and the associated flow characteristics, making it useful for the evaluation of flow patterns in acute stroke, Moyamoya disease, AVMs, dAVFs, and large intracranial aneurysms. Additionally, 4D-CTA can provide information regarding the relationship between intracranial tumors and pertinent arterial vascular supplies and venous drainage pathways that may be useful to surgical planning [14].

4D-CTA possesses several unique clinical advantages relative to other luminal imaging techniques. Good correlation exists between 4D-CTA and DSA for the detection and grading of intracranial high-flow vascular malformations [15, 16]. Retrograde cortical venous flow can be visualized with 4D-CTA [15]. 4D-CTA can more accurately grade collateral vascularity in the setting of acute ischemic stroke than conventional CTA [15, 20, 22].

4D-CTA uses ionizing radiation for image acquisition and therefore exposes patients to nontrivial amounts of radiation. Because multiple image acquisitions are performed, the cumulative radiation dose for 4D-CTA is significantly higher than conventional CTA [15]. Despite this fact, the cumulative radiation dose of 4D-CTA is likely still lower than that of catheter DSA [16]. 4D-CTA generates thousands of images as part of a single study. As such, significant computing power is necessary for fast and efficient image post-processing [15].

First-pass CE-MRA

First-pass CE-MRA is a useful imaging modality for the follow-up evaluation of coiled intracranial aneurysms [2]. Compared to noncontrast 3D TOF-MRA, first-pass CE-MRA is more sensitive to the presence of aneurysm neck remnants [51] and can more accurately classify these remnants [2]. The detection of aneurysm neck remnants with 3D TOF-MRA can be improved, however, by scanning with intravenous contrast [51]. Unlike non-CE-MRA techniques, first-pass CE-MRA is relatively insensitive to artifacts generated by turbulent flow and saturation effects [28].

Unlike other MRA techniques, first-pass CE-MRA requires accurate timing of contrast bolus arrival to ensure that the maximum volume of contrast is within the target vessel lumen at the time of scan initiation [2]. The accuracy of first-pass CE-MRA in detecting vascular lesions such as brain aneurysms is limited by the enhancement of adjacent venous structures if timing is delayed [2]. An obvious example of this is the presence of a cavernous segment ICA aneurysm that is surrounded by the cavernous sinus. After aneurysm coiling, the aneurysm wall may demonstrate thin peripheral enhancement which is postulated to represent some combination of peripherally distributed intra-aneurysmal thrombus, vasa vasorum within the adventitial layer of the aneurysm wall, and/or ingrowth of vascularized tissue about the coil mass due to inflammation or healing. Regardless of the underlying etiology, these findings may be confused with a residual aneurysm sac on all types of CE-MRA [51].

TR-CE-MRA

TR-CE-MRA provides a combination of structural and hemodynamic information about the intracranial vasculature. It provides for evaluation of the complex flow patterns of intracranial AVMs and dAVFs [2]. This technique facilitates the visualization of arterial feeders, the nidus, and draining veins in AVMs [2, 52–54] and allows for the evaluation of dAVFs due to its sensitivity for the detection of early venous drainage [2].

TR-CE-MRA readily depicts vascular lesions with arteriovenous shunting [24, 30]. It can determine the directionality of flow through vascular structures and has excellent suppression of background tissue signal [24]. Unlike other luminal imaging modalities, TR-CE-MRA is relatively insensitive to the shape and timing of the contrast bolus [29]. The start of image acquisition coincides with the start of intravenous contrast injection, and no timing bolus is required [30].

TR-CE-MRA commonly exhibits a trade-off between spatial and temporal resolution, with greater temporal resolution coming at the expense of spatial resolution. Additional loss of SNR can result from the incorporation of acceleration techniques, such as parallel imaging. Blurring of vessel walls commonly occurs when aggressive undersampling is applied [32]. In consideration of the vascular disease being evaluated, balancing the spatial and temporal resolution and imaging acceleration for optimal disease evaluation is paramount.

TOF-MRA

TOF-MRA is routinely used to image the cervical and intracranial arteries. It provides a useful screening tool for asymptomatic patients at higher risk for cerebral aneurysm [33]. 3D TOF-MRA has proven particularly useful in imaging the intracranial vasculature due to its higher spatial resolution, whereas 2D TOF-MRA is typically reserved for evaluation of the cervical vasculature [55].

The scan time for TOF-MRA is longer than first-pass CE-MRA [56]. Signal loss of in-plane flow due to saturation effects can occur, giving the appearance of pseudostenosis or pseudo-occlusion. Signal loss occurs in vessels with complex or turbulent flow, as can be seen in areas of moderate- or high-grade vascular stenosis, large intracranial aneurysms, or arteriovenous malformations, secondary to intravoxel dephasing [55]. In the setting of arterial stenosis, dephasing artifacts can overexaggerate the degree of stenosis or even present a stenosis as an occluded artery [2].

PC-MRA

PC-MRA is an excellent imaging technique for the visualization of the intracranial veins, allowing for accurate detection of dural venous sinus thrombosis [2]. PC-MRA also offers excellent background signal suppression, improving visualization of the intracranial vasculature [33, 55].

The use of multiple flow-encoding gradients lengthens the scan time for PC-MRA relative to other non-CE-MRA techniques [2]. As with TOF-MRA, PC-MRA experiences signal loss in vessels with turbulent flow because of intravoxel dephasing. This imaging artifact can lead to an overestimation of luminal stenosis [55]. PC-MRA is susceptible to patient motion because of mask subtraction that occurs as part of image generation [55]. PC-MRA image quality is largely dependent upon appropriate Venc parameters. Finally, PC-MRA image post-processing is complex, making it a time- and resource-intensive endeavor [56].

ASL-MRA

ASL-MRA is an imaging technique that provides complete suppression of background tissues, allowing for high-quality angiographic image generation with high CNR [33]. ASL-MRA is well-suited for imaging vascular regions with rapid flow such as the extracranial or intracranial carotid arteries [56].

ASL-MRA is associated with long image acquisition times, requiring two image acquisitions so that the signal from background tissues can be subtracted out of the final image set [33, 55, 56]. Because image subtraction is performed, ASL-MRA is sensitive to patient motion causing misregistration artifact [33, 56]. Like other non-CE-MRA techniques, in cases of slow flow, ASL provides decreased vascular coverage due to a combination of signal losses and the delayed arrival of spin-labeled protons [33]. This is particularly important in the setting of high-grade stenosis causing severe reduction in downstream flow velocities or in patients with poor cardiac output.

Luminal Imaging Characterization of Cerebrovascular Pathology

Intracranial Aneurysms

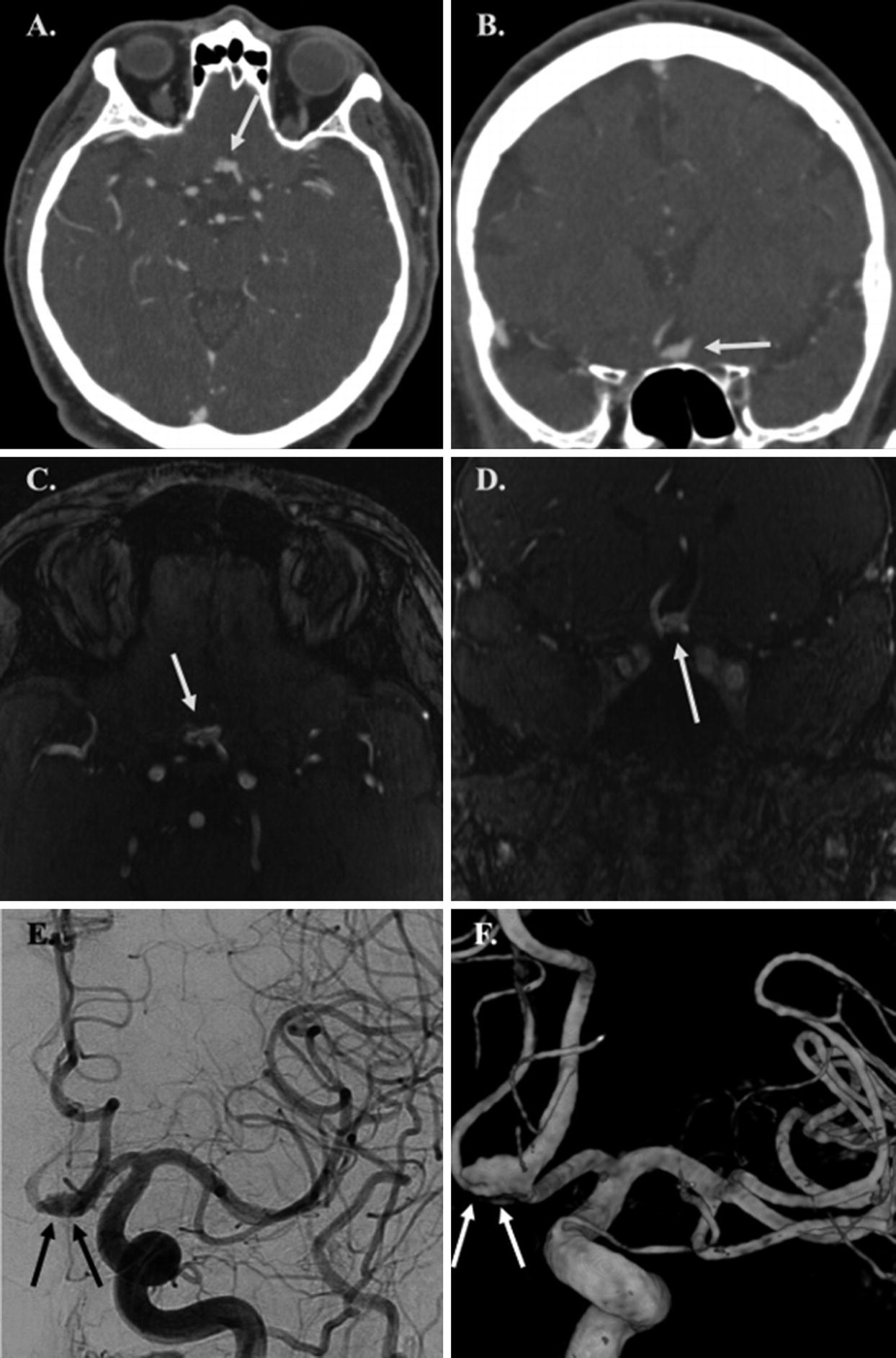

Intracranial aneurysms are pathological vessel wall outpouchings which can be located anywhere within the intracranial circulation but are commonly encountered at vessel bifurcation points. DSA better characterizes geometric and morphologic features of aneurysms, flow characteristics of aneurysms, as well as the lesion’s relationship to the arterial vasculature and small branch origins when compared to CTA and MRA [36]. DSA has a higher sensitivity and specificity for the detection of small supraclinoid blister aneurysms which prove difficult to identify with either CTA or MRA. Additionally, DSA outperforms CTA in the detection of small dissecting aneurysms, perforator artery aneurysms, and small peripheral infectious or myxomatous aneurysms [38].

DSA allows for accurate aneurysm assessment following treatment with microsurgical clipping, endovascular coiling, or flow diversion. After such interventions, DSA accurately identifies residual aneurysm necks and incompletely thrombosed aneurysm sacs [57] as well as identifies in-stent stenosis following flow diverter placement [57]. While the use of flow-diverting stents has posed many technical challenges to both conventional CTA and MRA evaluation, DSA has not encountered the same issues. Unlike these other luminal imaging modalities, DSA can accurately and reproducibly quantify the degree of in-stent stenosis following flow-diverter placement [58–60].

Information regarding aneurysm size, dome morphology, direction of dome projection, and location in the intracranial circulation can all be attained from CTA with a high degree of accuracy [61]. With conventional CTA, the sensitivity and specificity for aneurysm detection are more than 80% [62]. Unfortunately, CTA assessment of treated aneurysms proves significantly more difficult. Assessment of the aneurysm neck proves particularly difficult. The use of metallic streak artifact reduction techniques paired with iterative and noise-reduction filters is emerging as a promising CTA imaging technique for the evaluation of treated intracranial aneurysms [63].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree