Fig. 6.1

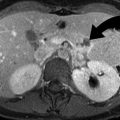

Acute diverticulitis (a–c) Contrast-enhanced CT scan study of the abdomen demonstrates inflamed diverticulum (arrowheads) arising from the ascending colon. There are pericolonic inflammatory changes seen around the inflamed colonic diverticulum. (d) Contrast-enhanced CT scan study of the abdomen demonstrates inflamed diverticulum arising from the distal descending colon. There is colonic wall thickening and pericolonic inflammatory changes

Although graded compression ultrasound has been shown by some to have a sensitivity of 90 % for the diagnosis of diverticulitis, it has not gained widespread acceptance in the USA. Ultrasound is however considered the most appropriate test in the evaluation of left lower quadrant pain in women of childbearing age.

Complications

The complications of acute diverticulitis include abscess, perforation, and colovesical fistula. An uncommon complication of recurrent diverticulitis of the colon is giant colonic diverticula. A giant colonic diverticulum is more than or equal to 4 cm in diameter and is believed to result from narrowing of the diverticular neck, creating ball-valve mechanism where air can enter the diverticula but cannot escape out (Fig. 6.2).

Fig. 6.2

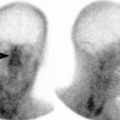

Giant sigmoid diverticulum. (a) Scout film of the abdomen demonstrates a 10-cm-diameter air-containing cavity in the pelvis which corresponds to a giant sigmoid diverticulum (arrowheads) in a patient with recurrent episodes of diverticulitis. (b) Contrast-enhanced CT scan study of the pelvis demonstrates a giant sigmoid diverticulum arising from the sigmoid colon. Small amount of rectal contrast is present within the lumen of the large diverticulum. (c, d) Contrast-enhanced CT scan study demonstrates inflammatory thickening of the wall of a giant sigmoid diverticulum (arrowheads), arising from sigmoid colon

Diverticulitis accounts for two-thirds of the vesicoenteric fistulas. Inflamed colon may adhere to the urinary bladder wall and may cause a fistula. These patients may have pneumaturia and fecaluria. The flow through the fistula predominantly occurs from the large bowel to the urinary bladder and is often indicated by the presence of air in the urinary bladder lumen (Fig. 6.3).

Fig. 6.3

Colovesical fistula. (a, b) Coronal and sagittal reformations of the abdomen demonstrate colovesical fistula (arrow) extending from the sigmoid colon to the urinary bladder dome. There is air identified within the urinary bladder lumen, secondary to the fistulous communication with the colon

Treatment

The treatment of acute diverticulitis is most often conservative with antibiotic therapy. Image-guided pigtail catheter drainage is used to treat abscess and avoids the need for multistage surgery for acute diverticulitis. CT-guided catheter drainage has a 70–90 % success rate in treating a post-diverticulitis abscess. Abscess less than 3 cm in diameter may be managed conservatively, without drainage or surgery. When a collection is more than 4 cm in diameter, CT-guided catheter drainage is often preferred, followed by referral for surgical treatment (Fig. 6.4). Eventual surgical resection of the segment of colon is recommended in all patients who develop abscess.

Fig. 6.4

Diverticulitis abscess. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT scan study of the pelvis demonstrates a well-defined abscess cavity (arrow) in the sigmoid mesocolon with surrounding inflammatory changes. (b) Contrast-enhanced CT scan study demonstrates decrease in the size of the pelvic abscess after placement of a pigtail drainage catheter

Segmental Omental Infarction

Omental infarction is a rare cause of acute abdomen, which most often simulates acute appendicitis on clinical exam. It is seen in younger age group patients than acute epiploic appendagitis. Segmental omental infarction is the result of vascular compromise, either due to torsion or vascular thrombosis. It typically occurs on the right side of the omentum due to embryologic variation in the blood supply.

Omental torsion may result from conditions which cause sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure such as coughing, sneezing, Valsalva, or heavy meal. Although most cases of segmental omental infarction is idiopathic, it can be associated with adhesions, hernias, surgery, intra-abdominal inflammation, congestive heart failure, obesity, strenuous exercise, digitalis administration, recent Whipple surgery/splenectomy surgery, and trauma.

The typical CT findings of omental infarction include a cake-like inflammatory fatty mass or whirled fatty structure, most commonly in the right lower quadrant (Fig. 6.5a, b) [6]. Unlike acute epiploic appendagitis, omental infarction is most commonly on the right side, may or may not about the colon, and does not demonstrate ring sign around the inflamed fat. While typical acute epiploic appendagitis is less than 3.5 cm in diameter, omental infarctions are much larger (typically >5 cm) [7].

Fig. 6.5

Segmental omental infarction (a, b) and acute epiploic appendicitis (c–e). (a) Contrast-enhanced CT scan study demonstrates a 7-cm-diameter omental fat density inflammatory lesion (arrowhead) in the upper right lower quadrant of the abdomen of a 6-year-old patient. (b) Noncontrast CT of a patient with segmental omental infarction demonstrates a midline inflammatory fatty lesion anteroinferior to the left lobe of the liver. (c) Ultrasound of a patient with acute epiploic appendagitis demonstrates a focal heterogeneously hypoechoic lesion (curved arrow) located just deep to the left anterior abdominal wall musculature. (d, e) Axial and coronal contrast-enhanced CT scan study demonstrates an oval, fat density lesion (straight arrow) in relation to the sigmoid colonic wall with surrounding inflammatory changes. The high-density central dot corresponds to thrombosed or congested vessel within the torsed epiploic appendage. Omental infarction

Fig. 6.6

Inflammatory bowel disease. (a) Plain radiograph of the abdomen demonstrates thumbprinting (arrowheads) involving the transverse colon in a patient with ulcerative colitis. (b) Contrast-enhanced CT in a patient with ulcerative colitis shows symmetrical and continuous involvement of the entire rectum and sigmoid colon by inflammatory proctocolitis (arrowhead). There is sigmoid wall thickening, mucosal enhancement, and pericolonic inflammatory densities. (c) Plain radiograph of the abdomen in a patient with Crohn’s colitis demonstrates a featureless segment of the transverse colon

Fig. 6.7

Crohn’s colitis. (a) Double-contrast barium enema examination demonstrates a sinus tract arising off the hepatic flexure (arrowhead). (b) Coronal CT reformation demonstrates inflammatory thickening of right transverse colon (arrow), secondary to Crohn’s colitis. A sinus tract (arrowhead) is seen extending from the splenic flexure to the right subhepatic location

Segmental omental infarction is a self-limited condition which is best managed conservatively using Motrin. Majority of the patients are asymptomatic within 10 days of the treatment.

Acute Epiploic Appendagitis

Epiploic appendages are finger-shaped fat-containing pouches which arise off the surface of the colon and are surrounded by the visceral peritoneum. The most common location of inflammation of an epiploic appendage is adjacent the sigmoid colon and usually affects adult people in fifth to sixth decades [5]. The reason for the presence of epiploic appendagitis in the left abdomen in 80 % of cases is because of the higher number of epiploic appendages present adjacent to the sigmoid colon.

Torsion of epiploic appendages can lead to vascular occlusion and infarction. Inflamed epiploic appendage can cause bowel obstruction from adhesions and can get detached from colon to produce intraperitoneal loose body [5, 8]. It has also been rarely reported to cause intussusception and abscess formation.

Clinically, the patients may present with acute left lower quadrant pain, nausea, fever, and diarrhea or constipation [5]. When it involves the left lower quadrant, it is clinically most often mistaken for sigmoid diverticulitis. When it affects the cecum, it is clinically most often mistaken for acute appendicitis. Because of the clinical misdiagnoses, patients with primary epiploic appendagitis can get unnecessary hospitalization and treatment. The clinical management of acute appendagitis includes conservative treatment with pain medication.

Imaging

Although ultrasound has been occasionally used in diagnosing acute epiploic appendagitis, CT is the imaging tool of choice in making the diagnosis. The CT findings include a pedunculated fatty lesion, 1.5–3.5 cm in length, and associated with surrounding inflammatory stranding, hyperdense ring, high-attenuating central dot, and less commonly adjacent thickening of the colon wall (Fig. 6.5c–e) [5]. The parietal peritoneum deep to the anterior abdominal wall may be thickened. The ultrasound findings are similar to CT study and may include hypoechoic rim surrounding a hyperechoic focal lesion.

A central high-attenuation focus within the fat is a helpful finding which is believed to represent a thrombosed or congested vessel. Since it is seen in 54 % of the cases, its absence does not rule out the diagnosis of acute epiploic appendagitis. There is usually no colonic wall thickening [7]. The CT changes of acute epiploic appendagitis tend to resolve in all patients within 6 months.

The differential diagnosis of an inflammatory fat-containing lesion on CT includes acute epiploic appendagitis, mesenteric panniculitis, acute diverticulitis, trauma, omental contusion, omental metastases, and liposarcoma. Although omental infarction can have an appearance similar to that of epiploic appendagitis, it lacks the hyperdense ring that is seen in all patients with epiploic appendagitis. Majority of the cases of acute epiploic appendagitis are self-limited and can be treated with pain management using analgesics.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Crohn’s disease is a chronic granulomatous inflammatory disease that involves the entire gastrointestinal tract with transmural and discontinuous lesions which most often affects the distal ileum and right colon [9]. The transmural inflammation is commonly associated with deep ulceration and sinus/fistula formation.

Ulcerative colitis is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory disease that most often demonstrates continuous involvement of the rectum and distal colon and rectum mucosa [10].

The common modes of presentation of inflammatory bowel disease include abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, vomiting, and fever. The patients with Crohn’s disease may have associated arthritis, ocular inflammatory diseases, gallstones, and skin lesions [11].

Imaging

For the initial presentation of suspected Crohn’s disease in patients with abdominal pain, fever, and diarrhea, CT enterography is considered the most appropriate imaging modality. The second-line imaging test for suspected Crohn’s disease is small bowel follow-through study. For adult and pediatric patients with known Crohn’s disease, presenting with fever, abdominal pain, and leukocytosis, routine contrast-enhanced CT is considered the imaging modality of choice. CT enterography involves the use of neutral oral contrast and imaging performed 45 s after intravenous contrast.

The CT findings include bowel wall enhancement, wall thickening, mural stratification, prominent vasa recta, and mesenteric inflammation. The mural stratification (Target or halo sign) is produced by soft tissue density mucosa, low-density submucosa (edema or fatty infiltration), and soft tissue density muscularis propria. Imaging also allows differentiation between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (Tables 6.1 and 6.2).

1. Continuous involvement from rectum to colon |

2. Mucosal granularity and stippling |

3. Indistinctness of haustral folds |

4. Collar button ulcers |

5. Inflammatory pseudopolyps |

6. Backlash ileitis |

7. Presacral space widening (>1.5 cm) |

1. Lymphoid hyperplasia: 2 mm filling defects in the wall |

2. Aphthoid ulceration: small, 1 mm diameter superficial ulcerations with radiolucent halo |

3. Deep ulcerations, sinuses, and fistulas |

4. Colonic wall thickening: more with Crohn’s disease |

5. Bowel strictures: often asymmetrical |

6. Anorectal fissures, abscess, and fistulas: more commonly with Crohn’s disease |

In pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease with mild symptoms, MR enterography is considered the most appropriate imaging modality because of its high sensitivity and specificity, similar to CT enterography. Ultrasound is the second-line imaging modality in similar clinical scenario and suffers from the disadvantage of operator dependence. Ultrasound may be useful in diagnosing colonic inflammatory diseases, in particular when equivocal results are obtained by other imaging techniques, because of its ability to see wall thickening (≥4 mm), target sign, sluggish peristalsis, and pericolonic extension of the disease. MR imaging may be also used, in particular when recurrent studies are needed, and allows excellent soft tissue contrast without radiation exposure [10].

Complications and Treatment

The complications of inflammatory bowel disease include abscess, fistulas, and bowel obstruction [2]. Acute flare-up of Crohn’s disease is usually treated with anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids. Surgery is the therapeutic tool which is reserved for nonresponsive disease, complications, and very ill patients.

Pseudomembranous Colitis

Pseudomembranous colitis, also called C. difficile colitis, is a life-threatening condition caused by Clostridium difficile that produces two exotoxins and leads to colonic mucosa to generate a protein-rich membrane (pseudomembrane). Toxin A is responsible for colitis and allows Toxin B to enter the cell. The bacterium has a widespread presence in the hospitals and is the cause of up to 20 % of diarrhea associated with antibiotic therapy [12].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree