Key Facts

- •

Pedal complications are very common in the diabetic population due to neurologic and vascular disease and cause significant morbidity.

- •

Neuropathic arthropathy results from a combination of sensory, motor, and autonomic dysfunction.

- •

The Schon classification is based on the location of Charcot joints and their severity.

- •

Neuropathy, ligamentous injury, tendinopathy, and muscle atrophy lead to foot deformity and abnormal biomechanics resulting in callus formation. Progressive breakdown of the callus leads to focal ulceration and superimposed infection.

- •

The most accurate way of determining the presence of osteomyelitis is to find the ulcer and sinus tract and closely assess the adjacent bones, either clinically or more accurately by imaging.

- •

It is often difficult to distinguish neuropathic arthropathy from osteomyelitis. Neuroarthropathy commonly occurs in the midfoot, whereas osteomyelitis is seen predominantly in the metatarsal heads and hindfoot. Nuclear scintigraphy is frequently used to differentiate the two.

Diabetes has become a health care problem of increasing concern in the United States as the number of people affected has risen tremendously over the past 2 decades. From 1980 through 2003, the number of Americans with diabetes has nearly tripled and will continue to rise to near epidemic proportions. Approximately 15 million persons in the United States alone have been estimated to have diabetes, and this number is predicted to rise to 22 million by 2025.

The diabetic foot has had a significant impact both on society and on individual patients. An estimated 15% to 20% of all individuals with diabetes in the United States will be hospitalized at some point for a foot-related complication. Health-economic consequences are enormous, with costs of healing an infected ulcer without amputation totaling $17,500. However, amputation is often a necessary treatment in the diabetic patient, with approximately 50,000 lower extremity amputations performed each year in the United States at a cost of over $1 billion. Diabetes is the most common cause of nontraumatic amputation, with a rate 15 times higher among the diabetic population compared with the nondiabetic population. The incidence of complication involving the contralateral foot is also increased within 2 years after surgery, which reflects the weight-bearing shift onto the intact extremity. The overall quality of life following amputation is reduced in the diabetic patient as well.

Early care and management of the diabetic foot is extremely important and can improve quality of life. Effective interventions include optimizing glycemic control, intensive podiatric care, debridement of calluses, orthotics, and in some cases surgical revascularization, including bypass grafts and peripheral angioplasty. These interventions may contribute to a decreased risk of foot ulcerations and therefore favorable consequences to the individual and society.

The foot is susceptible to multiple complications that are largely due to the cumulative effects of neurologic and vascular disease. Diabetic patients show evidence of peripheral vascular disease, both macrovascular and microvascular, which lead to chronic ischemia, decreased ability to fight infection, and poor wound healing. Diabetic patients also exhibit peripheral neuropathy, motor and sensory as well as autonomic, which contribute to the pedal disorder. The decreased sensation of the diabetic foot allows unrecognized microtrauma with incomplete healing, the formation of calluses, and consequent tissue breakdown and ulceration. Superimposed infection may occur as a result of bacterial colonization via direct implantation and contiguous spread. Furthermore, repetitive trauma to the foot and ischemia result in neuropathic osteoarthropathy, or joint deformity.

Imaging is essential in the evaluation of the sequelae of the diabetic foot. It is key for identifying vascular disease and soft tissue, articular, and bony complications. Radiographs and computed tomography (CT) are useful for osseous anatomic information. Bone and leukocyte scintigraphy are often used to distinguish infection, although localization is sometimes imprecise. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become the primary imaging tool for evaluation of the diabetic foot, demonstrating both osseous and soft tissue infection in addition to improved anatomic depiction.

PATHOGENESIS

A combination of metabolic dysfunction, neuropathy, immunopathy, and peripheral vascular disease contribute to the development of the diabetic foot. On the microvascular level, diabetic patients show thickening of the capillary basement membrane and accumulation of advanced glycation end products on the membrane, impairing transfer of molecules and contributing to an abnormal hyperemic response. Vasomotor changes and formation of arteriovenous shunting lead to decreased perfusion to bone, muscle, skin, and subcutaneous tissue, which is thought to play a role in the onset of both ischemic changes and the neuropathic foot.

Macrovascular disease affects the diabetic population and occurs in the form of atherosclerosis. This complication is believed to arise from metabolic mechanisms increased by hyperglycemia, including nonenzymatic glycation, diacylglycerol-protein kinase C activation, sorbitol-polyol pathway, and redox alterations. These abnormal pathways promote accelerated atherosclerosis, particularly in the lower extremity. An additional contributor to atherosclerosis is the cell mediator, nitric oxide, which interferes with cell adhesion to vasculature and leads to smooth muscle proliferation and increased negative vascular tone.

Neuropathy primarily originates from the direct effects of hyperglycemia. The “sorbitol theory” explains the mechanism by which excess glucose enters an alternative pathway and is converted to sorbitol. The by-product of this pathway is that the redox potential of the cell is lowered, thus impairing fatty acid metabolism, reducing axonal transport. A second mechanism for the development of neuropathy is nonenzymatic glycosylation. This activity occurs in several tissues including the nerve, vascular basement membrane, and connective tissue. Exposure of these tissues, including nerve myelin, to hyperglycemia leads to covalent bonding of advanced glycation end products, which disrupt protein function.

Sensory neuropathy, seen as distal sensory loss and numbness, results in failure to recognize foot trauma. Motor neuropathy and ischemia lead to atrophy of the intrinsic muscles, promoting foot deformity. This structural change leads to loss of the plantar arch, increased pressure points in several areas, and ulcer formation. Autonomic neuropathy causes impaired thermoregulation of the microvasculature and anhidrosis. As a result, diabetic patients often have dry scaly skin with cracks and fissures, which provides an entrance for infection. Autonomic dysfunction may manifest as a failure of the parasympathetic system with a loss of regulation of heart rate or sympathetic failure with dysregulated neurogenic control of blood flow.

Furthermore, hyperglycemia and metabolic derangements impair the immune system, causing increased susceptibility to infection. Hyperglycemia impairs neutrophil function and diminishes aspects of host defense such as chemotaxis and phagocytosis. Impaired leukocyte function leads to poor granuloma formation and impaired wound healing. Studies have shown that up to 50% of diabetics have an inadequate leukocyte response to severe foot infection. The pedal manifestations of these derangements include osteomyelitis and septic arthritis ( Table 10-1 ).

| Photogenesis | Mechanism | Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular disease | Small vessel disease | Decreased perfusion, neuropathy |

| Large vessel disease | Decreased perfusion | |

| Nerve disease | Motor | Muscular atrophy, deformity, pressure points |

| Sensory | Numbness, failure to recognize trauma | |

| Autonomic | Dry skin, portal for infection | |

| Immunologic abnormalities | Increased susceptibility to infection |

VASCULAR DISEASE

Peripheral vascular disease is very common in the diabetic patient and is four times more likely to develop in such a patient than in the general population. It is characterized by both atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the lower extremities and arteriosclerotic disease, which is more diffuse, premature, and accelerated in the diabetic patient. Plaques develop circumferentially along the vessel, and calcification occurs within the tunica media. Perfusion is compromised, resulting in chronic ischemia of the lower extremity.

Atherosclerosis is found most commonly at the aortic bifurcation, at the tibial trifurcation, and in the superficial femoral artery at the adductor hiatus. Peripheral vascular disease tends to spare the internal iliac, profunda femoris, and peroneal arteries. Patterns of atherosclerosis have been classified based on vessel involvement. Type 1 disease involves the aorta and common iliac arteries. Type 2 disease involves the aorta, common iliac, and external iliac arteries. Type 3 disease extends from the aorta and iliac to the femoral, popliteal, and tibial arteries. Diabetic patients often have patterns of type 2 and 3. In addition to the major vessels, the distal arterioles and capillaries of the diabetic patient are affected as well and to a greater degree than in nondiabetic individuals. Atherosclerotic narrowing of the vessels in the upper extremity is fairly uncommon but may be seen in some cases.

Radiographically, proximal arterial disease is seen as calcification of the vessel wall and angiographically as stenosis.

Calcification of the vessels distal to the Lisfranc joint in patients younger than 50 years is fairly specific for diabetes.

Conventional angiography, CT angiography, and MR angiography have all played a role in the diagnosis of peripheral vascular disease of the diabetic patient. In each of these imaging techniques, arterial stenosis is seen as a localized narrowing of the vessel, abrupt cutoff of blood flow, or nonvisualization of a vessel branch. With chronic disease, collateralization of vessels may develop in the attempt to increase perfusion to the extremity ( Figure 10-1 ). Although these imaging modalities are accurate in the diagnosis of macrovascular disease and are useful to assess the role of bypass grafts or angioplasty with stents to treat proximal disease, they are not effective in diagnosing the more important microvascular disease. Revascularization techniques may improve blood flow to distal vessels, but disease of the periphery still exists and is more difficult to manage.

Current theory suggests that the microvascular disease may not be anatomic, but rather part of the autonomic dysfunction. Dysfunctional sympathetic control of the neurovascular system leads to capillary hypertension, impaired vasoconstriction, arteriovenous shunting of blood, and consequently decreased perfusion. Injury to the foot is less likely to heal in the face of disease of distal vessels as a result of baseline ischemia and decreased vascular reserve. Callus formation and gradual breakdown in these ischemic areas promotes the development of ulceration and infection.

MRI of peripheral vascular disease is promising. This imaging can be anatomic and show proximal major vessels. However, distal imaging and the assessment of tissue perfusion are more important. One method of assessing tissue perfusion is a comparison between precontrast and postcontrast imaging sequences after administration of intravenous gadolinium. Ischemia and tissue devitalization can be detected as a focal or regional lack of soft tissue contrast enhancement.

Lack of tissue enhancement after intravenous gadolinium can indicate tissue ischemia and devitalization.

Surrounding soft tissue may show increased enhancement representative of hypervascular, reactive tissue. T1-weighted and T2-weighted images show nonspecific alterations in signal, and therefore contrast enhancement is necessary to recognize devitalization. Ischemic tissue that has not yet devitalized may show subtle MRI changes, such as mildly decreased enhancement in comparison with surrounding tissue ( Figure 10-2 ). Arterial spin labeling is an alternative method, not requiring the use of contrast, to obtain similar information.

With the loss of adequate blood supply, gangrene may ensue. Gangrene can be classified as wet or dry, meaning superinfected or not, respectively. Gangrenous tissue shows localized soft tissue loss, mostly in the distal digits. This is often easy to identify on radiographs but is sometimes more difficult to see on MRI.

Soft tissue air may be seen as low-density (dark) structures on radiographs or CT or as signal voids in areas of devitalization on MRI. Gas may be a sign of overlying infection; however, it does not always imply gas gangrene, as it may be seen when an overlying skin ulceration allows air to enter the underlying soft tissues.

Not all gas within soft tissues in diabetic patients indicates infection. Gas may be introduced into the soft tissues through an ulcer without infection being present.

It is important to note that underlying infections such as osteomyelitis and abscess may not enhance within the necrotic area; in these cases, T1-weighted and T2-weighted images should be used to diagnose infection. Furthermore, even using these signs, false-negative studies may occur.

Finally, in areas of chronic foot ischemia accompanying diabetes, bone infarction is not rare. Bone infarcts are demonstrated by longitudinally oriented regions of signal abnormality in the fatty medullary cavity. They have well-defined margins and a serpiginous configuration. Surrounding marrow, if noninfected, is typically normal. It is not uncommon to see multiple bones infarcted in a region of chronic, even fairly mild ischemia.

NEUROPATHY

Neuropathic osteoarthropathy is a complication of diabetes that is sometimes overlooked clinically or is misdiagnosed. This deforming, destructive arthritis is suggested to result from sensory, motor, and autonomic dysfunction. First, the diabetic patient experiences diminished sensation of the distal extremities, classically referred to as having a “stocking and glove” distribution. This sensory neuropathy leads to multiple episodes of minor trauma to the foot with the patient unaware of the injury or the inadequate healing. Immunopathy and chronic baseline ischemia further contribute to the delayed wound healing. Second, motor neuropathy leads to intrinsic foot muscular atrophy and some minimal calf muscle atrophy. This results in shifted weight bearing of the lower extremity and exacerbates the articular injury. Third, autonomic dysfunction occurs involving both sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, leading to soft tissue change and accelerated ulceration. Neuropathic osteoarthropathy or Charcot’s arthropathy is the product of this multifaceted pathologic interplay.

Charcot’s neuroarthropathy has been further explained by two main theories. The first is a neurotraumatic mechanism in which the joints are insensitive to pain and proprioception and therefore undergo destruction from repetitive microtrauma. The second theory suggests that joint destruction is secondary to a neurally stimulated vascular reflex causing periarticular bone resorption and ligamentous insufficiency.

Ligamentous injury is a significant contributor to neuropathic arthritis. Tendon injury occurs as well, at an increased incidence, particularly in the posterior tibialis tendon, promoting deformity. Tendon and—more significantly—ligamentous injury, in addition to muscular atrophy, joint injuries, and microtrauma, cause a severe foot deformity with arch collapse leading to deformities such as the “rocker bottom” foot. These effects on the peripheral nervous system of the diabetic patient gradually lead to alteration in the distribution of plantar pressure, progressive ulceration, and finally superimposed infection.

Multiple classification systems have characterized diabetic neuroarthropathy into several patterns. Schon classified Charcot joints based on the location and degree of involvement ( Table 10-2 ). There are four patterns of involvement, each divided into three subtypes. The first pattern is Lisfranc, the second is the naviculocuneiform, the third is the perinavicular, and the fourth is the transversal tarsal pattern. The staging system allows for the prediction of disease progression and sites where future ulceration may occur as well as assessing risk for infection. Thus neuropathic arthropathy can occur at multiple locations including the Lisfranc joint, the hindfoot and ankle, the talonavicular joint, and the metatarsophalangeal joints.

| Type | Pattern |

|---|---|

| I | Lisfranc |

| IA | Breakdown along medial side of Lisfranc joints, primarily the first, second, and third metatarsocuneiform joints; hallux valgus possible; no rocker bottom |

| IB | Medial rocker from excessive abduction of foot. Minimal fullness under the fourth and fifth metatarsocuboid joint but no plantar lateral rocker bottom |

| IC | Extension plantarly of medial rocker toward the lateral side of midfoot under the fourth and fifth metatarsocuboid joint. Central rocker often ulcerates, with risk for infection |

| II | Naviculocuneiform |

| IIA | Instability of naviculocuneiform joint, lowers medial arch, leads to fullness under fourth and fifth metatarsocuboid joints |

| IIB | Medial arch lowers further, but deformity is occurring more proximally in medial foot, therefore no medial rocker. Later rocker develops under the fourth and fifth metatarsocuboid joints |

| IIC | Extension of lateral rocker to central and medial plantar region of foot. Prominence can ulcerate, with risk for infection |

| III | Perinavicular |

| IIIA | Avascular necrosis of navicular or displaced fracture of navicular. Minimal lowering of medial arch, fullness under fourth and fifth metatarsocuboid joint from decrease in lateral arch height |

| IIIB | Fragmentation of navicular, dorsal subluxation on the talus, shortening of medial column. Lateral rocker develops under fourth and fifth metatarsocuboid joint |

| IIIC | Rocker bottom shifts more proximally under cuboid toward midfoot. Talus is plantar flexed and navicular is dorsally located on neck of talus. Dorsal translation of medial column may be complete, with cuneiform metatarsals dorsally on neck of talus. Ulceration and infection likely |

| IV | Transverse tarsal pattern |

| IVA | Lateral subluxation of navicular on talus with abduction of foot and valgus of calcaneus. Dorsal translation of cuboid relative to calcaneus. Central-lateral fullness over calcaneocuboid joint |

| IVB | Progressive adduction of foot on head of talus, decreased height of medial arch. Plantar central rocker under calcaneocuboid joint |

| IVC | Destruction of calcaneocuboid articulation or dorsal translation of cuboid relative to calcaneus. Extreme abduction of navicular on talus and complete dislocation may occur. Central proximal rocker because posterior calcaneal tuberosity is non–weight bearing. All weight on distal end of calcaneus and cuboid. Medial rocker under navicular and central rocker under calcaneus. Osteomyelitis of distal calcaneus or talus is often seen because it is uncovered by navicular |

Neuroarthropathy can be identified in the acute or chronic stage. In the acute form, there is edema, erythema, tenderness, and associated warmth that may mimic cellulitis. As the disease progresses, joint fragmentation and/or destruction occur, as well as subluxation, bony proliferation, and sclerosis. The diabetic foot then exhibits a chronic deformity.

Radiography is often the first imaging modality used in the diagnosis of the neuroarthropathic foot ( Table 10-3 ).

| Classification | Findings |

|---|---|

| Acute | Swelling |

| Slight subluxation | |

| Slight bone resorption | |

| Chronic | “The D’s”: |

| D eformity | |

| D islocation | |

| D estruction | |

| D ebris | |

| No D emineralization | |

| Hypertrophic | Sclerosis of juxtaarticular bone |

| Generally normal bone density | |

| Large osteophytes | |

| Periosteal bone proliferation | |

| Atrophic | Erosion, bone loss |

| Destruction | |

| Dislocation | |

| Fracture |

Imaging findings in the acute phase of the Charcot foot may be absent at the time of presentation. If radiographic change is evident, it may be minimal soft tissue swelling and slight resorption of bone around the affected joint. There also may be an offset of the arch or slight subluxation. Findings on radiography in the chronic phase of the neuropathic foot are more prominent and include deformity, dislocation, destruction, and debris. The arthropathy appears on radiographs as a mixed pattern of both bone destruction and production, as opposed to a predominant proliferative or erosive pattern as seen in the rest of the body.

Hypertrophic neuroarthropathy is manifested by sclerosis of the marginal bone, preservation of bone density, and large osteophytes. Osteophytes that form are ill defined and grow large in the late stage of the arthropathy. Periosteal new bone formation is also characteristic. This can extend up to the mid metatarsals and mimic infection.

Hypertrophic neuroarthropathy is characterized by the “D’s” including d ebris, d estruction, d islocation, and no d emineralization ( Table 10-3 ).

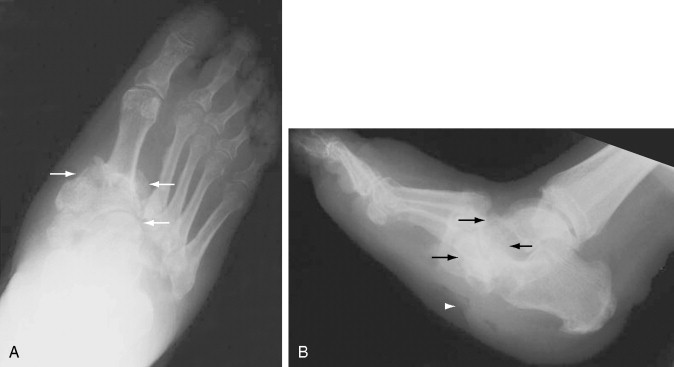

Atrophic neuroarthropathy shows joint erosion, destruction, and disorganization. The fragmentation of articular surfaces causes bony debris and intraarticular bodies to form, and parts of the tarsal bones may dissolve. Fractures of neighboring bones are often found in neuropathic arthropathy. They are usually spontaneous or occur with minimal trauma and tend to be horizontal fractures, as opposed to those caused by trauma, which are spiral or oblique. The most common finding on radiography is the Lisfranc fracture dislocation with destruction and fragmentation of the tarsometatarsal joints ( Figure 10-3 ). Calcaneal fractures, talar collapse and angulation, and less commonly distal fibular fractures occur as well.

The patterns of radiographic changes in the neuropathic foot are found at the tarsometatarsal joints, the metatarsophalangeal and interphalangeal joints, and the anterior medial column of the foot, with talus, talonavicular, and naviculocuneiform destruction. In the forefoot, osteolysis of the distal ends of the metatarsals combined with a broadening of bases of the proximal phalanges produce “pencil and cup” deformities. Flattening or fragmenting of the metatarsals may occur as well. Dorsiflexion of the toes accompanied by plantar subluxation of the metatarsal heads leads to ulceration under the heads of the metatarsals or at the dorsal aspects of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. The midfoot and hindfoot experience continuous trauma and exhibit a rapidly destructive process with fragmentation, subluxation, and dislocation ( Figure 10-4 ).

The Charcot process has been well characterized by the presence of bone destruction, joint destruction, and subluxation or dislocation and fragmentation, as well as periosteal reaction. These changes are characteristically found in the midfoot of the diabetic patient. In a group of neuropathic patients with foot ulcers, there was a 16% prevalence of hypertrophic Charcot changes.

A three-phase bone scan has been a useful tool in demonstrating neuropathic disease. Sensitivity of bone scintigraphy is high for neuropathic arthropathy at 85% to 100%; however, specificity is low at 0% to 54%. The latter is a particular problem, as the usual clinical question is whether infection is present. Neuropathic arthropathy has been divided into five scintigraphic stages according to uptake ( Table 10-4 ). Stage zero has swelling and pain clinically. Radiographs are normal while the bone scan shows increased radiouptake in all three phases. In stage one, radiographs show erosion and periarticular cysts, and the bone scan shows increased uptake in phases I and II with diffuse uptake in phase III. Stage two and three show joint subluxation on radiographs, and the bone scan shows increased uptake in all three phases. Stage four is a clinically stable patient with the rare fusion of joint spaces and increased uptake on the delayed phase; phases 1 and 2 are normal. Therefore in the early stage of neuropathic joints, uptake is seen on the early and late phase of the bone scan due to bone turnover and increased vascularity at the articular surface. In the late stage of disease, uptake is seen on the delayed images only.

| Stage | Radiographic Appearance | Scintigraphic Appearance |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Normal | Increased uptake in phases I–III of bone scan |

| Stage 1 | Erosion and cystic changes |

|

| Stage 2 | Subluxation | Increased uptake phases I, II, III |

| Stage 3 | Dislocation | Increased uptake phases I, II, III |

| Stage 4 (rare, fusion, stable patient) | Bone fusion | Increased uptake phase III Normal phases I, II |

The use of bone scanning may be limited related to vascular disease in the diabetic patient where decreased perfusion may affect distribution and hence uptake of the radiotracer. Also, the amount of hyperemia in the acute stage of neuropathy is variable and therefore scintigraphy may not be accurate. Combined bone and radiolabeled white blood cell scans may be used for the detection of infection in the neuropathic foot. This combination has been found to be more specific in diagnosing osteomyelitis of the Charcot foot than MRI or radiography.

The combination of bone scanning and white blood cell scans may be helpful in diagnosing osteomyelitis of the Charcot foot and may be more helpful than MRI.

MRI is somewhat nonspecific in the diagnosis of neuropathic arthropathy. The acute hyperemic stage is characterized by soft tissue edema and osseous edema with no bone destruction ( Box 10-1 ). Joint effusions are also common and show rim enhancement with contrast. Bone marrow edema and enhancement centered at the subchondral bone reflect the articular pattern of disease. Periarticular edema also occurs, and enhancement may be seen. Subcutaneous fat is preserved in this setting, which helps to differentiate this edema from cellulitis. Chronic neuropathic arthropathy shows dislocation or subluxation of the joints with bony proliferation at the joint margins. Fragmentation, debris, and deformity are prominent. Soft tissue edema is frequently seen in the diabetic foot, largely due to decreased venous drainage ( Figures 10-5 to 10-7 ).

ACUTE HYPEREMIA

Soft tissue and bone marrow edema

Joint effusions

May have contrast enhancement of periarticular bone

Adjacent fat is preserved (unlike infection)

CHRONIC NEUROPATHIC FOOT

Dislocation or subluxation

Debris

Deformity

Soft tissue edema

CALLUS

Subcutaneous mass-like density with low signal on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images

ULCERATION

Skin defect

Granulation tissue at the ulcer base shows low T1 and high T2 signal and contrast enhancement

CELLULITIS

Thickened skin

Reticulated subcutaneous tissue

Edema signal in the subcutaneous tissues (low signal on T1-weighted, bright signal on T2-weighted) similar to nonspecific edema but with poorly defined septal enhancement in patients with cellulitis

Gas (low signal foci on all sequences) in an area of absent enhancement raises the possibility of infection in devitalized tissue

SINUS TRACTS

May be difficult to see

May emanate from an ulcer

Postcontrast fat-suppressed images allow the hyperemic bright walls of the tracts to be delineated

ABSCESS

Focal fluid collection (intermediate to low signal on T1-weighted and high signal on T2-weighted images with thick low signal wall)

Wall enhancement after contrast

Adjacent soft tissues are edematous

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree