FIGURE 20-8. Axial views of contours of a patient treated with adjuvant IMRT after hysterectomy for endocervical adenocarcinoma. Small bowel (green), sigmoid (yellow-green), rectum (brown), bladder (yellow), CTV nodes (red), and CTV vagina (orange).

1. ANATOMY

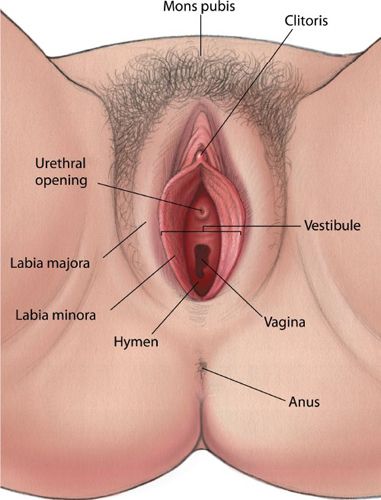

1.1. Vulva

• The vulva consists of all external genital structures including the labia majora, mons pubis, labia minora, clitoris, perineal body, vulvar vestibule containing the urethral meatus, hymenal remnant, greater and lesser vestibular glands, and the associated erectile tissues and muscles. Figure 20-1 shows the anatomy of the vulva.

• The vulva is bound by the anterior abdominal wall superiorly, the labial crural folds laterally, and the anus posteriorly.

• The labia majora form the lateral boundaries of the vulva and are composed of adipose and fibrous tissue. They fuse anteriorly to form the mons pubis, a hair-bearing region of tissue overlying the pubic symphysis. Posteriorly, they terminate 3 to 4 cm anterior to the anus where they are joined at the posterior fourchette.

• The labia minora are immediately medial to the labia majora and contain mainly connective tissue with little adipose tissue. Anteriorly, the labia minora divide into two parts with one part passing over the clitoris to form the prepuce and the other joining beneath the clitoris to form the frenulum. The duct opening for the greater vestibular glands (Bartholin glands) is situated at the junction of the labia minor and the vaginal vestibule.

FIGURE 20-1. External female genitalia. (From Westheimer R, Lopater S. Human Sexuality. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.)

• In addition to the clitoris, other midline structures below the mons include the urethral meatus, the vaginal opening, and the perineal body.

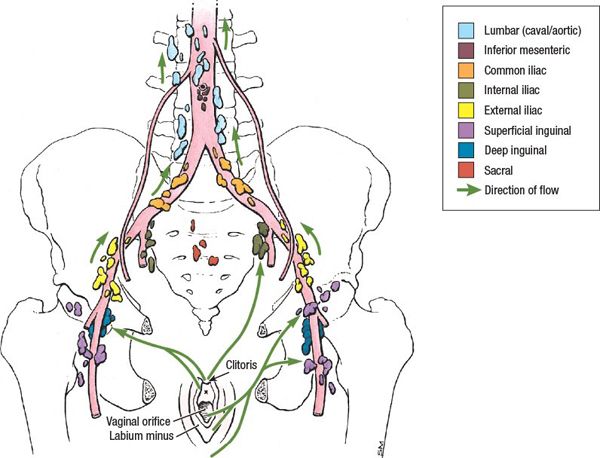

• Lymphatic drainage of the vulva and distal third of the vagina is primarily via the inguinal lymph nodes. These lymph nodes are found in the tissues overlying the femoral triangle which is bounded by the inguinal ligament superiorly, the sartorius muscle laterally, and the adductor longus muscle medially (Fig. 20-2).

1.2. Vagina

• The vagina is a hollow, pliable, muscular organ that extends from the cervix to the vulva. It averages 7 to 8 cm in length.

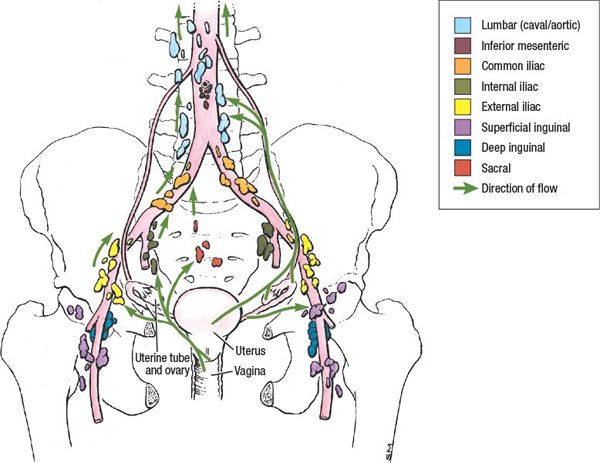

• Lymphatic flow within the vagina is complex with an extensive interconnected network. Lymphatics in the upper vagina drain primarily through the lymphatics of the cervix. The anterior upper vagina drains into the internal iliac and parametrial nodes, whereas the posterior vagina drains into the inferior gluteal, presacral, and anorectal nodes. The lymphatic drainage of the lower vagina follows the vulva with lymphatic flow into the inguinofemoral nodes and then to the pelvic lymph nodes. Lesions within the mid-vagina can drain through either route.1

• As a result of the complex network of lymphatics in the vagina, particularly the terminal branches of the vaginal artery and adjacent to the vaginal wall, the external iliac lymph nodes are at high risk even in patients with distal vaginal tumors and as such should be addressed during the treatment planning.

1.3. Endometrium and Cervix

• The uterus is a hollow, muscular, thick-walled organ that lies in the pelvic cavity between the bladder and rectum. The uterus is divided into the fundus, body, and isthmus. The wall consists of an inner glandular mucosa and an outer smooth muscle myometrium.

• The cervix is an extension of the lower uterine segment and generally varies in length, averaging 3 to 4 cm, but this is dependent on age of the patient and other cervical or uterine factors. The cervix is divided into two components, the upper or supravaginal cervix and the lower or vaginal cervix. The external os is located centrally within the vaginal portion and connects to the endocervical canal, the internal cervical os, and the endometrial canal (Fig. 20-3).

FIGURE 20-2. Lymphatic drainage of the female pelvis. (Reprinted from Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009:244.)

FIGURE 20-3. Diagram of the uterus and vagina illustrating the parts of the uterus and the relationship of its cervix to the superior end of the vagina.

• Five paired ligaments support the uterus: broad, round, uterosacral, cardinal, and vesicouterine. The uterosacral and cardinal ligaments are uncommonly involved in uterine cancer, contrary to cervical cancer.

• Blood supply of the uterus is through the uterine artery, a branch of the hypogastric artery.

• Lymphatic flow from the uterus can occur through four main drainage channels: from the fundus, along the round ligaments, along the mesosalpinx and fallopian tubes, and in the folds of the broad ligament. The drainage patterns are reflected in the metastatic potential to the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes (Fig. 20-4).

• The lymphatic flow of the cervix is complex. The most dominant route is laterally from the cervix: lymphatics drain into the paracervical and parametrial lymph nodes to the internal, external, and common iliac chains. The other routes of drainage include the inferior and superior gluteal lymph nodes, and the superior rectal, presacral, and para-aortic lymph nodes.

2. NATURAL HISTORY

2.1. Vulva

• Over 90% of vulvar malignancies are squamous cell carcinoma. There are two distinct types:

º Keratinizing type generally occurs in older women and is unrelated to HPV infection, but associated with vulvar dystrophies. Verroucous carcinoma, a variant of squamous cell carcinoma has a cauliflower-like appearance and rarely metastasizes to lymph nodes, though it can be locally destructive.

FIGURE 20-4. Lymphatic drainage of the structures of the female pelvis. (Reprinted from Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009:244.)

º Classic, warty, or Bowenoid type is associated commonly with HPV 16, 18, and 33 and tends to occur more often in younger women.

• Vulvar cancers metastasize by a variety of methods:

º Direct extension to nearby organs including vagina, urethra, anus, clitoris.

º Lymphatic spread to regional lymph nodes can occur early even in women with small lesions. Most vulvar cancers spread initially to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes and then through to the deep femoral lymph nodes, followed by the pelvic lymph node chains. Lesions that are well-lateralized generally spread only to ipsilateral lymph nodes. Carcinomas of the clitoris or Bartholin glands can occasionally spread directly to the deep femoral and obturator lymph nodes, though this is rare in the absence of evident superficial inguinal lymph node involvement.

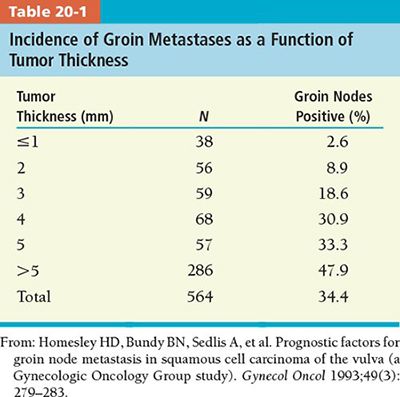

º The vulva is supplied by a rich network of lymphatics thus the risk of lymph node metastases is common. Risk of lymph node metastases increases with depth of stromal invasion. The risk of lymph node metastases in patients with <1 mm invasion is 3.1% versus 31% in patients with an invasion of 4 mm or greater (Table 20-1).

º Clinical evaluation of the groin nodes is inaccurate with more than 20% of palpably enlarged groin nodes ultimately histologically negative, and conversely approximately 20% of patients with clinically uninvolved groin nodes having pathologic evidence of groin metastases.2,3

º The presence of pelvic nodal metastases is rare in patients without clinically suspicious groin nodes or three or more positive uniteral groin nodes.4,5 It is also uncommon to observe metastases to the contralateral groin or to the deep pelvic nodes without ipsilateral groin metastases.

º Hematogenous dissemination can occur, but generally late in the course of the disease, and is rare in patients without inguinofemoral involvement.

2.2. Vagina

• The posterior vaginal wall along the upper third of the vagina is the most common site of presentation. Lesions of the mid-vagina are uncommon.

• Vaginal tumors can invade locally to involve the paravaginal tissues, bladder, urethra, rectum, and pelvic wall. If biopsies of the cervix or vulva are positive, the tumor cannot be characterized as a primary vaginal cancer.

• Lymphatic spread is determined by the location of the primary tumor. For apical lesions, drainage is primarily to the obturator and hypogastric nodes and then to para-aortic lymph nodes. Lesions in the distal third of the vagina drain initially to the inguinofemoral lymph nodes. However, due to the complexity of the lymphatic system, any of the nodal groups may be involved.

• Hematogenous metastases occur late in the course of the disease and most commonly include lungs, liver, and bone.

2.3. Cervix

• Invasive carcinoma of the cervix can grow as exophytic tumors protruding from the cervix into the vagina or as endocervical lesions causing expansion of the cervix with a relatively normal appearing surface.

• Cervix cancer can spread by direction extension into the low uterine segment, vagina, paracervical tissues by route of the broad and uterosacral ligaments, peritoneal cavity, bladder, or rectum. Extension into the ovaries is rare.

• In advanced disease, tumor may become fixed to the side wall by direct extension or from nodal involvement.

• Lymphatic spread of cervical cancer usually follows an orderly progression spreading first to the primary echelon nodes in the pelvis then to the para-aortic nodes, and then to distant sites. It is rare for para-aortic nodes to contain the first draining nodes.

• The risk of pelvic lymph node metastases increases with increasing depth of cervical invasion.6,7

• The most frequent sites of distant metastases are extrapelvic lymph nodes, lung, liver, and bone.

2.4. Endometrium

• The median age of diagnosis of uterine cancer in the United States is 61 years.8

• There are two types of endometrial carcinomas:

º Type I endometrial cancers are most common and account for approximately 70% to 80% of endometrial carcinomas. They are usually low grade with a generally favorable prognosis. They may be preceded by an intraepithelial neoplasm (atypical and/or complex hyperplasia) and are estrogen dependent.9

º Type II account for 10% to 20% of endometrial carcinomas. Histologies include grade 3 endometrioid carcinoma, serous, clear cell, squamous, mesonephric, undifferentiated. They are not necessarily associated with estrogen stimulation and occur in women who are older and postmenopausal. Prognosis is worse than with type I.

• Risk factors for disease include obesity, unopposed estrogen exposure, and tamoxifen.10–12

• Although endometrial cancer is most commonly sporadic, there are some genetic syndromes associated with increased risk of endometrial cancer including hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome or Lynch syndrome, which is an autosomal dominant cancer susceptibility syndrome.13,14

• The main route of spread of endometrial cancer is lymphatic dissemination.

3. DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

3.1. Signs and Symptoms

3.1.1. Vulva

• The most common presentation is an ulcer, plaque, or mass on the labia majora. Labia minora, clitoris, mons, and perineum are less commonly involved. Pruritus is also a common symptom associated with vulvar disease. Vulvar bleeding or discharge, dysuria, and an enlarged lymph node are less frequent symptoms.

• Pelvic pain may be associated with advanced disease.

3.1.2. Vagina

• The most common presenting symptom is abnormal bleeding.

• Other symptoms on presentation include malodorous discharge, mass, pain, dyspareunia, urinary (dysuria, hematuria, frequency) or gastrointestinal symptoms (tenesmus, constipation), and pelvic pain.

3.1.3. Cervix

• The most common symptoms at presentation are abnormal vaginal bleeding, discharge, and postcoital bleeding.

• Patients with early-stage cervical cancer may be asymptomatic. Patients with advanced disease may present with pelvic or lower back pain.

• Bowel or bladder symptoms such as dysuria, incontinence, urgency, hematuria or pelvic pressure suggest advanced disease.

3.1.4. Endometrium

• The most common symptom at presentation is postmenopausal vaginal bleeding.

3.2. Physical Examination

3.2.1. Vulva

• In addition to a history and physical examination, a complete pelvic examination and examination of the groins is mandatory.

• Careful examination of the vulva should be performed to determine the dimensions, distance from major midline structures including clitoris, anus, and urethral meatus.

• Approximately 5% of patients can have multifocal lesions, and a thorough examination of the perineum, anus, cervix, and vagina is required.

• Groins should be examined carefully as well in the supine position.

3.2.2. Vagina

• A history and physical examination in addition to a complete pelvic examination of the pelvis is mandatory.

• Cystoscopy and proctoscopy should be performed if there is clinical suspicion for advanced disease.

• Special attention should be paid to the size, location, and extent of the tumor and whether there is invasion into the paravaginal tissues and/or pelvic side wall.

3.2.3. Cervix/Endometrium

• In addition to a complete history and physical examination, careful pelvic examination should be performed. This should include an assessment of the external genitalia, vagina, and cervix.

• Speculum examination should take note of the appearance of the cervix, size and extension of the tumor on the cervix, and visual appearance of the mucosal surfaces of the vagina. Digital examination of the vagina should also note any mucosal irregularities.

• Bimanual examination should also be performed to assess the size and shape of the uterus as well as its position (anteverted/retroverted/axial), flexion (retroflexed/anteflexed), and presence of masses. Adnexa should be palpated for any tenderness or masses.

• Rectovaginal examination should also be performed to assess size of the tumor/cervix and extension into paracervical tissues. Note should be made of the mobility of the tumor, any nodularity, and distortion of the anatomy.

• Cystoscopy and proctoscopy should be performed if there is clinical suspicions for bladder or rectal invasion.

• Palpation of the groins as well as the supraclavicular fossa should be performed particularly in those patients with lower vaginal extension or advanced disease.

3.3. Imaging

• Intravenous pyelography and radiography of the chest are the only imaging studies allowed to impact a patient’s cancer stage according to the FIGO cancer staging system. However, these studies have largely been replaced by computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET).15

• For patients with larger tumors (≥2 cm), clinically palpable inguinal adenopathy, or suspected metastases, anatomic imaging of the abdomen and pelvis is appropriate. CT and MRI are equally effective at detecting positive lymph nodes with moderate sensitivity and specificity.16

• MRI is superior to CT, physical examination, and ultrasound in the evaluation of the extent of local disease spread including tumor size, depth of stromal invasion, and vaginal or parametrial extension in most gynecologic cancers.17 Figure 20-5 demonstrates vaginal extension in a patient with locally advanced cervical cancer.

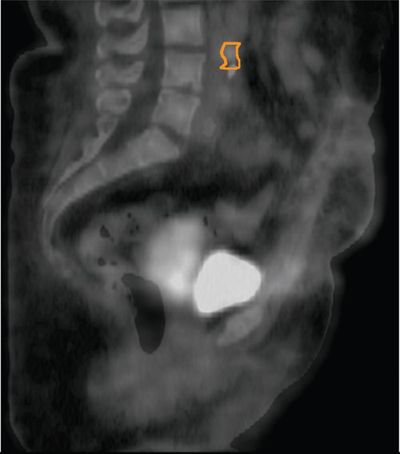

• 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET/CT has been shown to be superior to CT and MRI for detecting lymph node metastases in cervical cancer, and posttreatment residual FDG avidity on PET significantly predicts cause-specific survival.18–20 It is particularly useful in detecting para-aortic lymph node metastases in patients with cervical cancer and can be useful for determining the extent of external beam radiotherapy fields and for delineating the para-aortic nodal boost in this region (Fig. 20-6).21 Its use can be extrapolated to other gynecologic malignancies including vulvar and vaginal cancer. Although it has been less studied in other gynecologic malignancies such as vulvar and vaginal cancer, its use may also be appropriate given the similar natural history and epidemiology.

FIGURE 20-5. Patient with locally advanced cervical cancer with vaginal extension. Water-based lubricant is inserted into the vagina to aid in visualization of the extent of disease (green arrow). The white arrow denotes a fibroid in the uterus.

FIGURE 20-6. FDG-PET/CT on a patient with cervical carcinoma and FDG avid para-aortic and common iliac lymph nodes (contoured in orange).

• Anatomic imaging preoperatively for uterine cancer is generally not necessary if surgery is planned unless there is a suspicion for metastatic disease. In a rare patient for whom surgery is not planned, MRI is superior to CT for evaluating extent of myometrial invasion.22 For patients with uterine sarcoma or papillary serous histologies, anatomic imaging may be indicated to assess for metastatic disease.

4. PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

4.1. Vulva

• Lymph node status: One of the strongest predictors of prognosis is inguinal lymph node status.5

• Predictors for nodal metastasis: Tumor size, depth of invasion, tumor thickness, and the presence or absence of lymphovascular invasion all contribute to risk of lymph node metastases.

• Margin status: Incidence of local failure has been found to be higher with margins of <8 mm in the primary resected vulvar specimen.23

4.2. Vagina

• Stage is probably the most important prognostic factor for disease outcome.24–26

• Size: The prognostic importance of lesion size is controversial with several investigators noting a correlation with local recurrence, while others not.24–27

• Age: Age has been found to be an important prognostic factor in several studies with survival lower in patients above 60 years of age.24,28

• Location: The importance of disease location is controversial. Several investigators have noted improved survival for patients with disease located in the upper vagina compared to lesions in the distal vagina or involving the entire vagina.24,28,29

4.3. Cervix

• Lymph node involvement is one of the most important predictors of outcome with number, size, and location also influencing overall survival.30,31

• Lymphovascular space invasion is associated with a higher risk of recurrence independent of lymph node involvement.32,33

• Tumor size is one of the most important predictors of local recurrence and overall death from cervical cancer whether treated with radiotherapy34,35 or surgery.36,37

• Anemia: Low hemoglobin either pretreatment or during radiotherapy has been associated with poor prognosis.38,39

• Overall treatment time: Prolongation of overall treatment time has been shown to result in significantly decreased survival with radiotherapy.40

4.4. Endometrium

• Age: Women who are younger at diagnosis have a lower risk of recurrence.41

• Stage is the primary determinant of prognosis and recommendation for adjuvant therapy.

• Histology: Serous carcinomas have historically been considered to be more aggressive neoplasms even in the absence of myometrial invasion. Endometrioid type particularly stage I have an excellent overall prognosis.

• LVSI: The presence of lymphatic invasion may be important particularly in unstaged, early endometrial cancer. However, its prognostic significance may be reduced in well-staged node-negative patients.

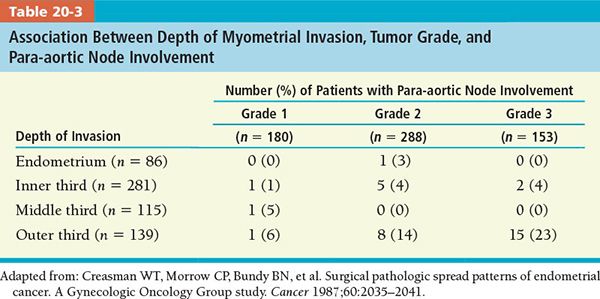

• Grade: The degree of differentiation may indicate tumor spread with higher rates of pelvic and para-aortic lymph node metastases as grade becomes less differentiated (Tables 20-2 and 20-3).42,43

• Pelvic Washings: The prognostic significance of positive pelvic washings is unclear particularly when it is the only evidence of disease outside of the uterus.44,45

• Lymph Node: Lymph node involvement particularly in the para-aortic region is associated with poorer prognosis.46

• Depth of Myometrial Invasion: The risk of lymph node metastases increases with the depth of myometrial invasion.42 Deep myometrial invasion is also correlated with a higher probability of extrauterine disease, treatment failure, and recurrence.

5. GENERAL MANAGEMENT

5.1. Vulvar Cancer

5.1.1. Surgical Management

• Small, minimally invasive tumors with <1 mm invasion beyond the superficial basement membrane have a very low (<1%) risk of regional lymph node metastases and can be treated with wide local excision alone.47 Any tumor that invades deeper than 1 mm beyond the most superficial basement membrane necessitates treatment of the regional nodes.

• Historically, surgical management of vulvar cancer consisted of en bloc resection of the vulva and inguinofemoral nodes which was associated with high rates of morbidity. Surgical excisions that remove less of the vulva and surrounding tissues are now more commonly used.48

• Radical local excision or radical partial vulvectomy is used to treat early-stage lesions. The excision should be taken down to the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm; a 1 cm tumor-free margin has been shown to decrease the risk of local recurrence and should be the goal unless doing so would compromise function of a major organ.23

• An inguinal femoral lymph node dissection is performed for all lesions greater than stage IA. The standard approach has been a radical lymphadenectomy that removes both the superficial and deep inguinofemoral lymph nodes, however, sentinel lymph node biopsy is under investigation as an alternative to reduce the morbidity.49

• For lesions that are well-lateralized (>1 cm from midline structures) and do not involve the anterior labia minora, a unilateral lymph node dissection may be performed. In a prospective GOG study, only 2.5% of 272 patients with non-midline vulvar tumors were found to have contralateral groin node metastases in the absence of ipsilateral lymph node metastases.47 A bilateral lymph node dissection should be performed if lymph node metastases are found on unilateral dissection.

• Pelvic nodal dissection is generally not performed due to the associated morbidity of the procedure. The current standard of care is to administer pelvic radiation therapy in the presence of regional nodal disease.

5.1.2. Postoperative Radiotherapy

• Adjuvant radiotherapy for positive nodes is recommended when there are two or more microscopically positive lymph nodes, one or more macroscopically involved lymph nodes, any evidence of extracapsular extension, or if only a small number of lymph nodes was sampled. Postoperative radiotherapy may also be considered when margins are <10 mm or in patients with small tumors for whom an inguinofemoral lymph node dissection is prohibited.

• GOG 37, which randomized patients to adjuvant pelvic and groin radiotherapy versus pelvic lymph node dissection, was stopped early due to a significant relapse-free survival between the two treatment arms at 2 years.50 At 6 years, there was no significant difference in overall survival in the entire population (P = 0.18) that may be attributed to the greater number of intercurrent deaths in the radiotherapy arm. There was a significant overall survival advantage with radiotherapy in the subgroup of patients with fixed or ulcerated nodes or two or more positive lymph nodes. As a result, pelvic lymph node dissection in patients with vulvar cancer is rarely performed with regional nodal radiation now being the standard of care for patients with metastases to two or more groin nodes.

• For patients with close or positive surgical margins, re-excision should be considered. If re-excision is not possible, postoperative radiotherapy has been shown to decrease risk of local recurrence.51

• For patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy for positive groin nodes, radiotherapy fields should include bilateral groins and the caudal external iliac lymph nodes on the ipsilateral side.

• In the absence of clinical or radiographic evidence of pelvic lymph node disease, the superior border of the radiotherapy fields should encompass the caudal external iliac nodes and should generally not extend more cephalad than the middle of the sacroiliac joints.

• Radiotherapy to the primary tumor is generally recommended in most cases requiring radiation of the inguinal and pelvic lymph nodes. Risk of recurrence in tissues shielded by a midline block has been reported after postoperative radiotherapy.52

5.1.3. Preoperative Radiotherapy

• Preoperative radiotherapy is often considered when tumors approximate normal tissues such as the anal sphincter, clitoris, clitoral hood or frenulum, pubic arch, or with disease involving more than the distal urethra or extending past the vaginal introitus.

• Moderate doses of preoperative radiotherapy followed by surgical excision of the residual tumor have resulted in pathologic responses in approximately 50% of cases.53–55

• In a phase II study by the GOG, 71 patients with FIGO stage III or IV disease were treated with preoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy delivered in a split-course regimen.56 Two patients had persistent unresectable disease; bowel and bladder continence preservation was achieved in all but three patients.

5.1.4. Definitive Chemoradiotherapy

• Definitive chemoradiotherapy may be considered for those for whom radical excision would require an ostomy as a result of bowel or bladder resection or for those with disease fixed to the bone. If residual disease remains after chemoradiotherapy, surgical excision is recommended.

• Although the studies are limited, the results have been reasonable with high rates of pathologic (70%) and clinical (48%) complete response (Table 20-4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree