Chapter 107 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affects approximately 1 million Americans; the incidence is equal in males and females, and the peak onset is in adolescence or early adulthood. Both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease represent a chronic inflammatory process without a known specific cause. Ulcerative colitis primarily involves the colon, whereas Crohn disease involves primarily the small intestine. The distinction between ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease defies classification in as many as 10% of patients. In children, the presentation may be nonspecific, leading to a delay in diagnosis that ranges from months to years.1 Clinical and laboratory markers for active disease are inadequate; therefore repeated imaging is common, especially in patients with Crohn disease.2,3 Chronic ulcerative colitis is an idiopathic inflammatory disease of the colon that typically affects older children and young adults; an infantile form has been described that is devastating and often fatal (e-Fig.107-1). The disease is characterized by mucosal inflammation, edema, and ulceration, and it is accompanied by submucosal edema in the early stages and fibrosis in the later stages. Transmural disease is uncommon. The disease may be localized in the distal colon, or it may spread to involve the entire colon and the terminal ileum. Skip areas are not characteristic, and their presence should raise the diagnosis of Crohn disease. e-Figure 107-1 Infantile ulcerative colitis in a 3-week-old girl with rectal bleeding. Crohn disease that affects the small bowel is discussed in Chapter 105. The disease can affect the colon and the small intestine. Two features that favor the diagnosis of Crohn disease over ulcerative colitis are the frequent sparing of the rectum, and the presence of skip areas in Crohn disease. Colonoscopy is often the initial examination in patients with suspected Crohn colitis, because it allows visualization of early changes and permits biopsy for diagnosis. Capsule endoscopy is commonly used in both adult and pediatric practice to visualize small-bowel abnormalities.4 Abdominal radiographs are most often nonspecific; typically, they show an absence of recognizable stool from affected colonic segments, and they may show evidence of mucosal edema or “thumbprinting” (Fig. 107-2).5 Patients with toxic megacolon should not undergo contrast enemas because of the high risk of perforation. Figure 107-2 Ulcerative colitis in a 14-year-old girl. Double-contrast barium enema, formerly the diagnostic imaging procedure of choice, has been replaced by colonoscopy with biopsy.4,6 Ulcerative colitis always affects the rectum, with contiguous proximal involvement. Skip areas do not occur, although different parts of the colon may not be equally affected. The terminal ileum may become secondarily affected when there is proximal colonic involvement; terminal ileal involvement is known as backwash ileitis (e-Fig. 107-3). Ultimately, the colonic wall becomes stiff, shortened, and tubular—the “lead pipe” colon—secondary to fibrosis of the submucosa (e-Fig.107-4). Late-stage disease produces presacral thickening, and retroperitoneal fibrosis is a rare complication. e-Figure 107-3 Ulcerative colitis with pseudopolyposis and “backwash ileitis” in a 15-year-old boy. e-Figure 107-4 Ulcerative colitis in a teenage girl. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be performed to investigate disease activity (abdominal pain, fever, or other symptoms), to diagnose complications, or to identify associated liver or biliary disease.7,8 When ulcerative colitis is active, cross-sectional imaging shows colonic wall enhancement with preservation of the smooth outer contour of the bowel (e-Fig.107-5). Surrounding fat stranding, mesenteric adenopathy, ascites, and, when perforation occurs, abscesses may also be evident, but extramural changes are much less common than in Crohn disease. In chronic ulcerative colitis, fatty changes may occur in the submucosa. e-Figure 107-5 Pelvic image from abdominal-pelvic computed tomography in a 12-year-old with known ulcerative colitis. As with ulcerative colitis, double-contrast barium enemas are seldom used today for diagnosis or monitoring of disease activity. Characteristic aphthous ulcers are small and superficial, seen as an elevated edematous halo with a central umbilication caused by barium in the shallow ulcer crater. Eventually, the inflammation becomes transmural, and the characteristic “rose thorn” configuration develops from deep ulcers that extend into the thickened bowel wall. A “cobblestone” pseudopolyposis pattern, similar to that seen in the small intestine, may be apparent: areas of edematous mucosa separated by areas of denuded mucosa and deep ulcerations.9 Small-bowel follow-through (SBFT) examinations can identify complications of diseases that affect the colon, and sequelae such as enteric fistulae (Fig. 107-6). Enteroclysis is helpful in unmasking focal areas of disease activity, such as strictures (e-Fig. 107-7). Crohn disease is more likely to lead to colonic strictures than is ulcerative colitis. Figure 107-6 Active Crohn disease with fistula formation on small-bowel follow-through. e-Figure 107-7 Crohn disease in a 12-year-old girl. CT and MRI are very useful in evaluation of the disease activity and its complications (see Chapter 105). Extent of extramural inflammatory changes and affected loops of bowel can be identified, as can development of abscess or colonic strictures (Figs. 107-8 and 107-9). Figure 107-8 Active Crohn disease in a 19-year-old. Figure 107-9 Magnetic resonance enterography of active Crohn disease in an 8-year-old boy. Newer imaging techniques include CT or MR enterography and CT or MR enteroclysis, which hold promise in improving the identification of disease activity and its complications. In CT enterography, the patient drinks a negative bowel contrast agent that distends the lumen more than water or traditional positive contrast and that does not mask vascular mucosal enhancement.10,11 CT enteroclysis, like small-bowel enteroclysis, is performed by using high-flow contrast introduced via nasoduodenal intubation. It is more invasive than enterography, but it provides a more controlled volume challenge to the bowel in order to define the presence of sinus tracts and fistulae and to differentiate stricture from inflammation of the bowel wall.12 CT enteroclysis has shown value in both detecting and excluding partial small-bowel obstruction and to guide specific therapies in these challenging patients. Increasingly, pediatric centers are using MR imaging, rather than CT to avoid radiation exposure.2 Magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) yields equivalent images of the small and large intestine and the intraabdominal organs.13,14 MRE is able to differentiate active inflammation from chronic inflammation in the layers of the bowel wall. Furthermore, CT and MRE are able to identify intraperitoneal complications such as fistulae and abscesses. MRE is also superior to CT for the diagnosis and management of perianal fistulae (Fig. 107-10).15–17 Some centers will image the entire abdomen and pelvis during these MR studies, because these patients may have inflammatory processes that involve the liver, pancreas, or biliary tree. Figure 107-10 Magnetic resonance image (MRI) of perianal fistula in a girl with a new diagnosis of Crohn disease. Initial treatment of both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease is with medical therapy to suppress the inflammation. However, the majority of Crohn patients (up to 80%) and one third of ulcerative colitis patients will end up needing surgery.18,19 The most common reasons for surgery in Crohn patients are small-bowel obstructions that do not respond to medical therapy because of bowel stricture or adhesion, and bowel perforation that leads to abscess. The most common reason for surgery in pediatric ulcerative colitis patients is active disease that does not respond to medical management or that leads to complications. Pseudomembranous colitis refers to severe colonic disease that occurs in approximately 15% to 25% of patients with antibiotic-associated diarrhea.20 The toxins produced by the bacterium Clostridium difficile are the most important cause of antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis.20,21 Other, less common toxins include those produced by C. perfringens and Staphylococcus aureus. The diagnosis is a clinical and laboratory one, it is more common in adults than in children, and it is rare in infants. Recently, studies have shown an association of recurrent C. difficile colitis in patients who had undergone remote appendectomy, suggesting a role of immune protection by the normal appendix.22,23 The radiographic findings are similar to those of the other colitides.24 Enema is not necessary and should be avoided, particularly in severe cases, to avoid the risk of perforation. Ultrasound (US), MR, or CT findings of pancolitis, with or without ascites, suggest the diagnosis in the appropriate clinical setting.25,26 The hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is a condition characterized by renal failure and the destruction of red blood cells. In children, it is related to foods such as undercooked meat in 90% of cases. The syndrome has a peak incidence of approximately 6.1 per 100,000 in children aged less than 5 years.27 Most cases are caused by a Shiga-like toxin produced by Escherichia coli serotype 0157:H7, found in raw or incompletely cooked beef and unpasteurized dairy products. Additional toxins are produced by other bacterial agents and include Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia, and Campylobacter. Hemorrhagic colitis is common. Renal and central nervous system complications can markedly affect the course and prognosis of this disease.28 This syndrome is most common during the summer months in children younger than 5 years of age. HUS usually has a gastrointestinal prodrome of diarrhea that precedes clinical evidence of acute renal failure, fever, anemia, and thrombocytopenia.28–30 A positive stool culture for the specific Shiga toxin–producing E. coli pathogen is definitive when positive. Serologic tests for antibodies to the Shiga toxin or to the lipopolysaccharide 0157 can be done, although these are not widely available.27 US, CT, or occasionally contrast enema is generally requested before the correct diagnosis is made. The findings consist of thickening of the wall of the involved bowel segment, more typically the colon, seen as “thumbprinting” on abdominal radiographs or contrast enema, and marked bowel wall thickening on CT or US.31 The involved segments are typically in continuity without skip lesions, and pancolitis can occur. Fat stranding and free fluid are often seen near the involved segments.32 Toxic megacolon and colonic perforation have been reported, and colonic strictures can occur as a late complication.33 Ionizing radiation treatment may cause acute inflammation during therapy. Later, chronic symptoms may be related to chronic inflammation or stricture. These changes can occur months to years after exposure and may involve the small bowel, colon, or rectum. Endarteritis, with end-vessel and microvascular circulation compromise, is the hallmark of supervening chronic ischemia.35 Radiation injury leads to activation of mucosal cytokines and increased levels of inflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL)-2, -6 and -8.36 Factors that affect the development of radiation colitis include patient comorbidities and, most importantly, the total radiation dose and the volume of bowel irradiated; radiation enteritis tends to develop in patients who have received on the order of 45 Gy, but it can occur with doses as low as 5 to 12 Gy.35,37 Diarrhea, cramping, and sometimes lower intestinal bleeding are the key clinical features of the acute phase, which is usually self-limiting. Eventually, fibrosis may occur, which leads to stiffness and loss of mobility of the affected portions of the colon. Chronic radiation colitis is a progressive, precancerous disease. Additional complications include partial obstruction and fragility of the bowel, which may culminate in perforation.36 Diarrhea and abdominal pain are additional symptoms in patients with chronic radiation colitis.36 Patients with radiation colitis do not usually undergo imaging examinations during the acute phase. Fluoroscopic imaging with either SBFT or contrast enema may delineate the chronic, fibrotic change to the affected colon (e-Fig. 107-11). CT and MR show relatively nonspecific findings of bowel wall thickening; however, the diagnostic finding is the distribution of these changes within the radiation port.35 e-Figure 107-11 Radiation colitis in an 8-year-old boy who had received radiation therapy for pelvic tumor 3 years earlier. Treatment is related to symptom relief and includes dietary changes with reduction of fat and lactose intake in addition to medications for nausea and diarrhea. Management of patients with chronic disease can be challenging; as many as 30% of patients my require surgery for fistulae, perforation, or bowel obstruction that does not respond to nonsurgical management.37 Neutropenic colitis, also known as typhlitis, is a necrotizing colitis primarily seen in children with hematopoietic malignancies, although it is also seen in children with solid tumors who undergo high-dosage chemotherapy.38 There are no definitive diagnostic criteria, although diagnosis is typically made when clinical and imaging findings are suggestive. The disease most often affects the cecum, hence the term typhlitis. The appendix may be involved and may produce clinical findings that mimic acute appendicitis.39 Edema and inflammation of the colon, including the distal ileum, may occur, and pneumatosis, perforation, or abscess may supervene. Radiographs are typically nonspecific and may show a focal ileus in the right lower quadrant. Often, a sentinel loop of dilated terminal ileum may be seen.40 Because the clinical presentation may mimic acute appendicitis, cross-sectional imaging is a critical diagnostic differentiating tool. US shows a markedly thickened cecal wall that may be either hyperechoic or hypoechoic.41 Intraluminal fluid and ascites may also be identified. CT shows marked thickening of the affected portions of the colon, which is usually more marked in the cecum; surrounding inflammatory change; and free fluid (Fig. 107-12).42 Extension of this process may involve the terminal ileum. Figure 107-12 Neutropenic colitis. The infectious colitides are usually caused by the same agents that affect the small bowel, discussed in Chapter 105. Imaging studies are rarely needed and, when performed, usually show nonspecific colitis.31 Fibrosing colonopathy was first described in 1994 in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) who received lipase replacement therapy.44 With the introduction of oral, enteric-coated, high-dose pancreatic enzyme medication, clinicians increased the amount of enzyme supplements to many of these patients. Some that received particularly high doses later came to medical attention with what has been termed fibrosing colonopathy. Children were at higher risk than adults, until strict dosage guidelines were implemented. This entity is now rare because of compliance with appropriate dosage recommendations.45 The most common contrast enema findings are colonic strictures, loss of haustra, and colonic shortening.46 The bowel wall may be thickened, and ascites may be evident on cross-sectional imaging. The vermiform appendix—a thin, tubular, intestinal diverticulum attached to the base of the cecum—is often referred to as a vestigial organ. Although conventional wisdom has long asserted that the appendix has no known function, there is evidence suggesting that it plays a role in immune function and as a reservoir for normal gut flora.22,23

Inflammatory and Infectious Diseases

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Presentation

Frontal (A) and lateral (B) projections during barium enema show tubular narrowing of the rectum and sigmoid colon (arrows) with an abrupt transition zone. The findings were suggestive of aganglionosis, but biopsy revealed ulcerative colitis.

Crohn Disease

Imaging

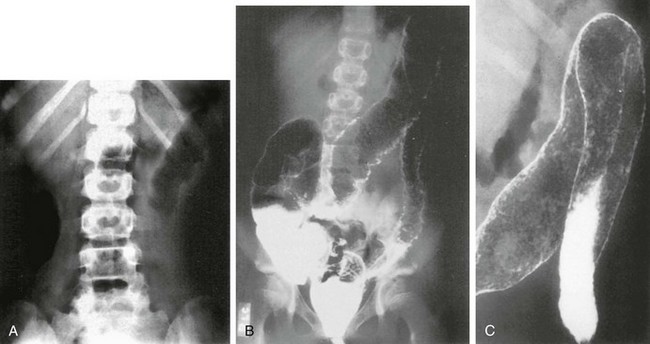

A, Abdominal radiograph shows “thumbprinting” of the distal transverse colon, suggesting submucosal edema. B, Double-contrast enema shows granularity and irregularity of the colonic mucosa. Small ulcerations are seen throughout the transverse colon and the descending colon. The entire colon was involved. C, Coned-down view of the splenic flexure shows multiple areas of pseudopolyps.

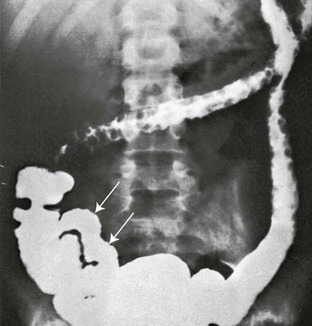

Multiple, round, marginal filling defects appear in the transverse and descending portions of the colon, reflecting retained islands of normal mucosa between areas of denuded mucosa. The terminal ileum (arrows) is rigid and lacks a normal mucosal pattern.

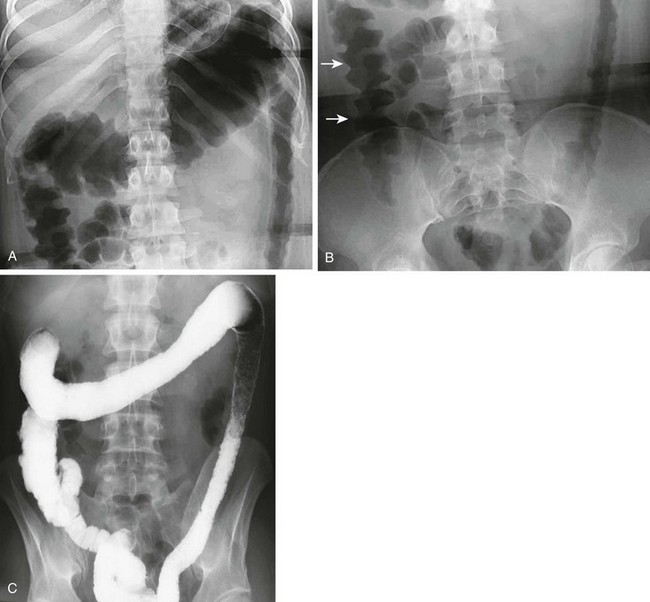

The radiographs show both acute and chronic changes of the colon resulting from ulcerative colitis. A, Abdominal radiograph shows that the transverse colon is very distended, and the left colon has a fixed, narrow “lead pipe” appearance. B, In the lower abdomen, the right colon is edematous, as seen by thumbprinting (arrows). C, The enema reveals the featureless and nondistensible left colon (“lead pipe”), resulting from fibrosis in chronic ulcerative colitis.

The examination shows a smooth outer wall with marked mucosal enhancement of the rectosigmoid colon and engorgement of pelvic vessels. (Courtesy Dr. Marta Hernanz-Schulman, Nashville, TN.)

Crohn Disease

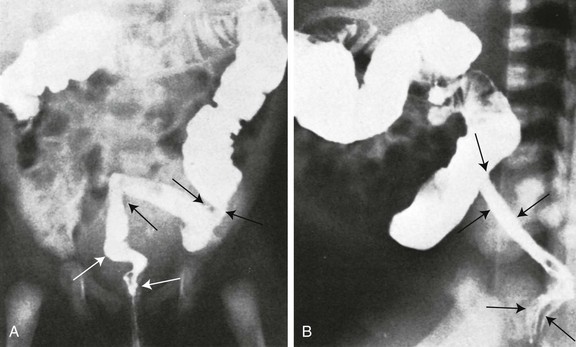

The fistula (arrow) extends between the ileum and the medial wall of the cecum.

The fluoroscopic enteroclysis image shows a stricture of the terminal ileum (arrow). The stricture led to proximal obstruction and dilation and required surgical resection.

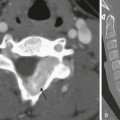

Computed Tomography shows the distended ileum (arrow) proximal to the thick-walled ileal loops and mesenteric stranding and vascular engorgement, resulting from active inflammation. Mural thickening and vascular engorgement of colonic segments is apparent. Positive oral contrast in the lumen interferes with evaluation of mucosal enhancement.

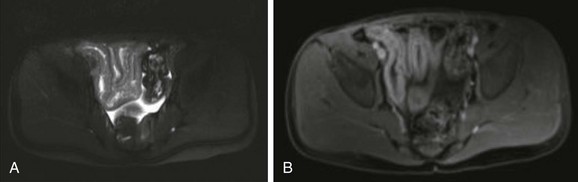

A, T2-weighted axial image of the pelvis shows several thickened, contiguous loops of terminal ileum that represent active Crohn disease. B, After gadolinium administration, bright signal enhancement appears in the bowel wall relative to normal adjacent colon and rectum.

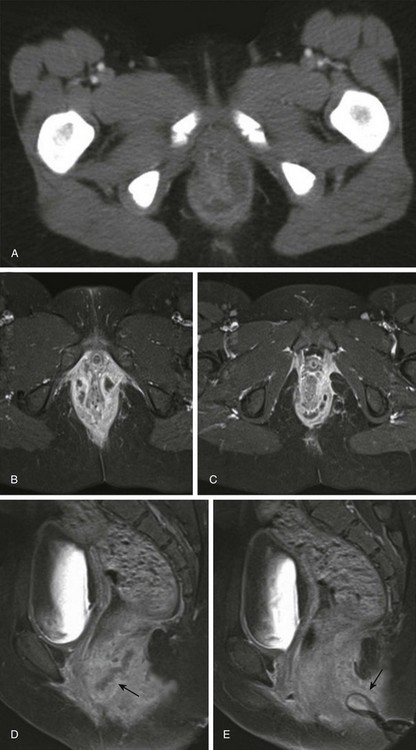

A, Initial axial computed tomography shows of perianal inflammation and small abscesses partially encircling the anus. B-C, Axial postcontrast fat-saturated MRI demonstrates the superior image contrast of the findings compared with CT. Exuberant inflammation (enhancement) and small abscesses nearly circumscribe the anus. D, Perianal abscesses in sagittal view (arrow). E, Superficial position of the drain (arrow) relative to the more deep position of the perianal abscess seen in image D. The patient required diverting colostomy to successfully treat her perianal disease. (Reprinted with kind permission of Springer Science+Business Media from Anupindi S, Ayyala R, Kelsen J, Mamula P, Applegate KE. Imaging of inflammatory bowel disease in children. In: Medina LS, Applegate KE, Blackmore CC, eds. Evidence-based imaging in pediatrics: optimizing imaging in pediatric patient care. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2010.)

Treatment

Pseudomembranous Colitis

Etiology

Imaging

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Etiology

Clinical Presentation

Imaging

Radiation Colitis

Etiology

Clinical Presentation

Imaging

Barium enema shows narrowing, rigidity, and loss of haustration in the distal descending and sigmoid portions of the colon.

Treatment

Neutropenic Colitis

Etiology

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) in an 18-year-old man with acute myelogenous leukemia, fever, and neutropenia. A, Axial CT image shows the marked thickening of the cecum and a small amount of free fluid. B, Coronal CT reformat shows pancolitis, affecting the right colon to a greater extent.

Infectious Colitis

Fibrosing Colonopathy

Etiology

Imaging

Appendicitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine