Erosive Osteoarthritis

Erosive osteoarthritis was first described by Kellgren and Moore in 1952 and reintroduced in 1961 by Crain, who called it interphalangeal osteoarthritis. He defined this disorder as a localized variant of osteoarthritis involving the finger joints, characterized by degenerative changes with intermittent inflammatory episodes leading to deformities and ankylosis. In 1966, Peter and Pearson coined the term erosive osteoarthritis, and Ehrlich in 1972 described it as inflammatory osteoarthritis, based on the clinical symptoms of swelling, tenderness, erythema, and warmth. It can be defined as a progressive disorder of the interphalangeal joints with severe synovitis, superimposed on the changes of degenerative joint disease. Although the cause is still unclear, several investigators have suggested hormonal influences, metabolic background, autoimmunity, and heredity as being involved.

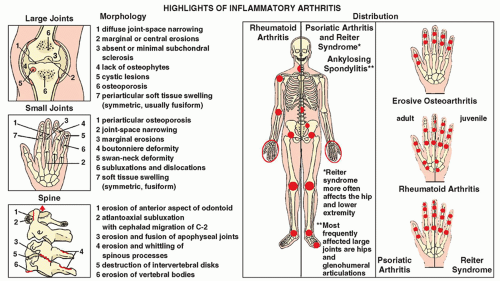

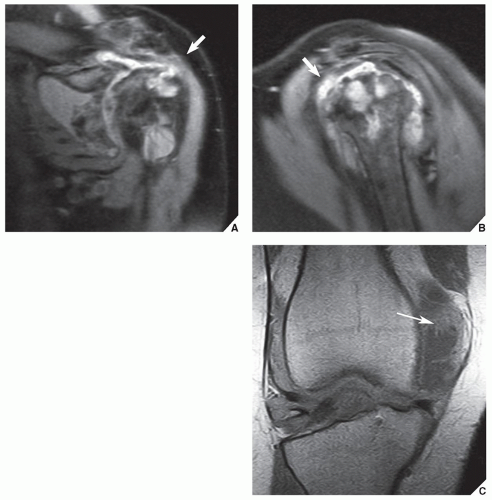

Erosive osteoarthritis is a progressive inflammatory arthritis seen predominantly in middle-aged women. Only rarely are men affected, with an estimated female-to-male ratio of 12:1. Patients’ ages range from 36 to 83 years, and mean age of onset is 50.5 years. This condition combines certain clinical manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis with certain imaging features of degenerative joint disease. Involvement is limited to the hands, with the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints being the most frequently affected. Large joints, such as the hip or shoulder, are only rarely involved. The arthritis usually begins abruptly and is characterized by pain, swelling, and tenderness of the small joints of the hands. Also described are throbbing paresthesias of the fingertips and morning stiffness.

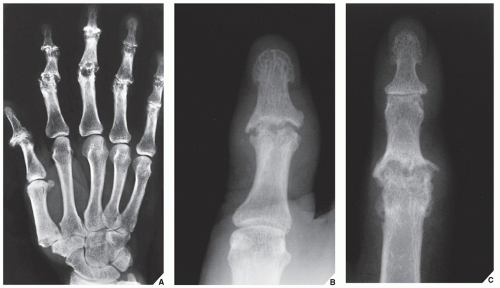

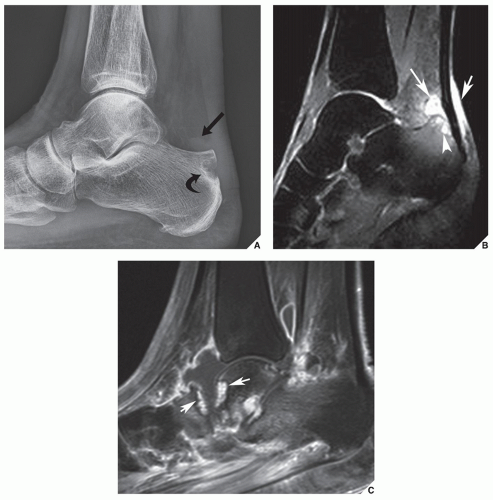

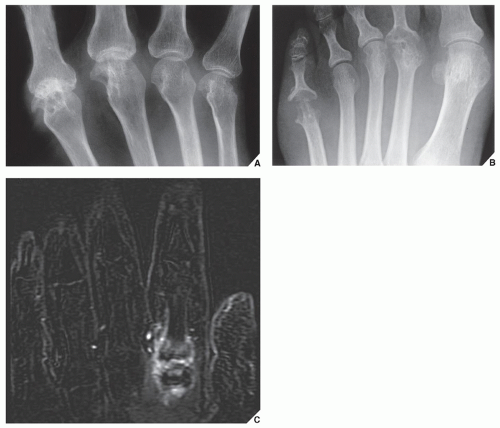

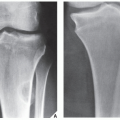

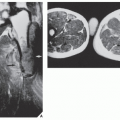

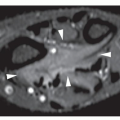

In the early stage of the disease, the main feature is symmetric synovitis of the interphalangeal joints. Later, this is followed by articular erosions, which exhibit a characteristic radiographic feature named the

gull-wing deformity by Martel. This configuration is seen as a result of central erosion and marginal proliferation of bone (

Fig. 14.2); Heberden nodes may also be present. Periosteal reaction taking the form of linear or fluffy bone apposition over the cortex near the affected joints is occasionally observed. Swelling of soft tissue, usually fusiform, may be present around involved articulations (

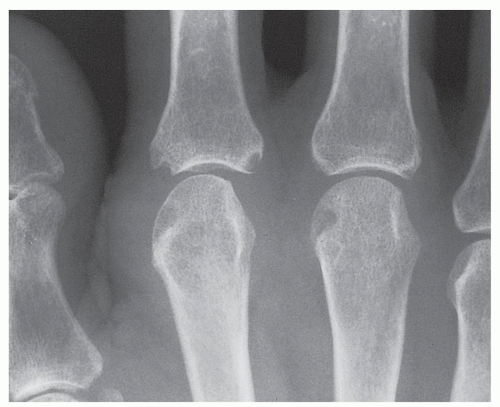

Fig. 14.2C); however, periarticular osteoporosis is rarely present. Later in the disease process, bone ankylosis of the phalanges may develop. Approximately 15% of patients with erosive osteoarthritis may have clinical, laboratory, and radiographic manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (

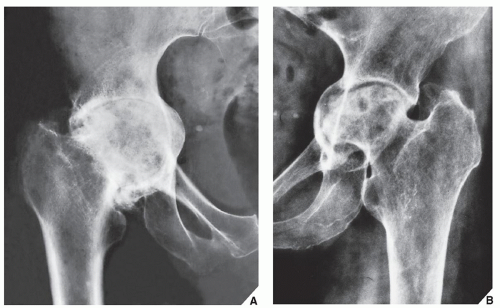

Fig. 14.3). The exact relationship between these two conditions is still unclear. Some investigators believe that erosive osteoarthritis is actually rheumatoid arthritis originating in unusual sites but subsequently progressing to the articulations that are more typically involved. Others suggest that each is a distinct entity, citing as evidence the fact that the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis does not resemble that of patients with erosive osteoarthritis, that the immunologic abnormalities commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis are absent in the latter condition, and that the serologic test for rheumatoid factor is negative.

Because, occasionally, imaging presentation of erosive and non-erosive osteoarthritis may be similar, the investigators were looking into the other means to distinguish these two conditions. The recent studies of serum biomarkers were very promising in this respect. They demonstrated elevation of myeloperoxidase, C-reactive protein, and serum levels of nitrated form of a marker of type II collagen denaturation (Coll2-1NO2) in patients with erosive osteoarthritis.

Occasionally, a variant of erosive osteoarthritis may be seen as one of the features of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. This rare systemic disorder also manifests with generalized gastrointestinal polyposis, hyperpigmentation of the skin, and nail atrophy.