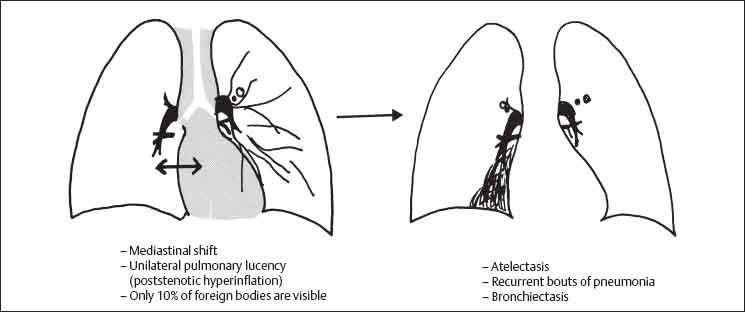

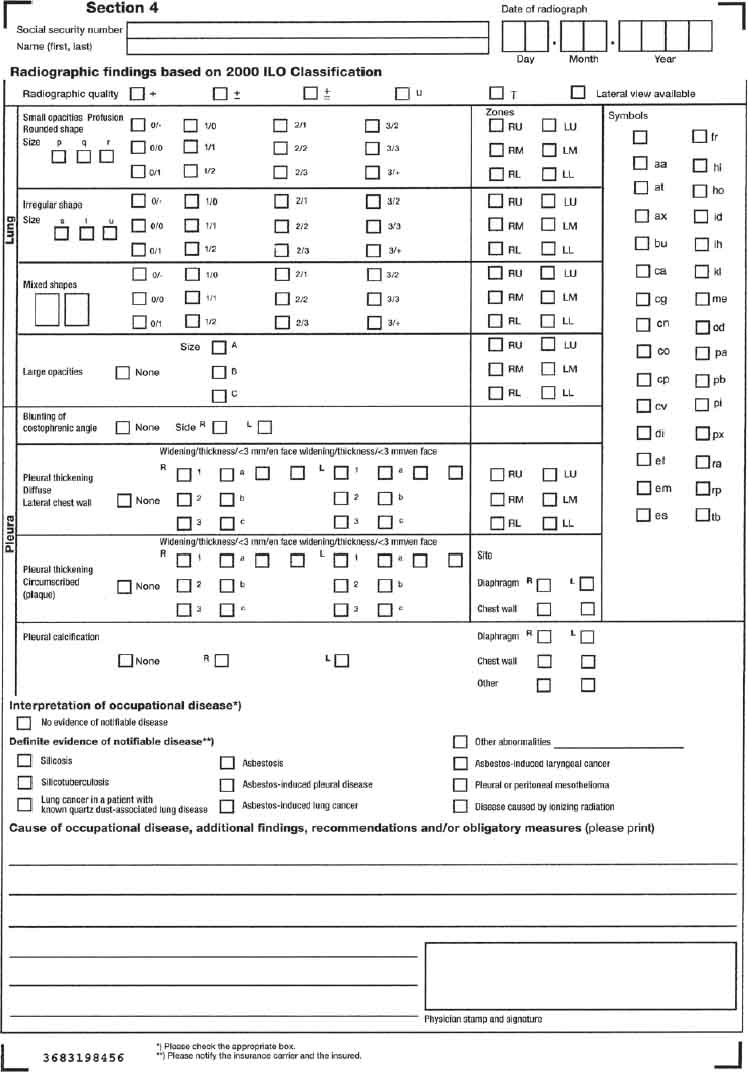

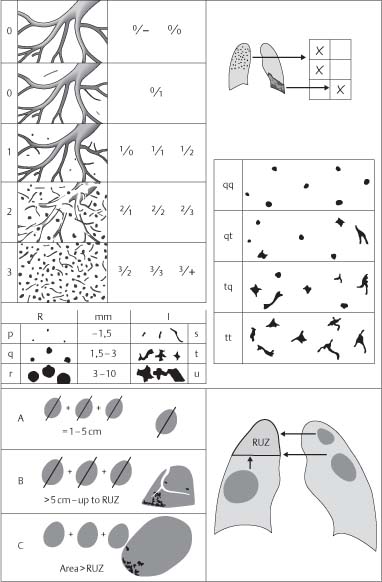

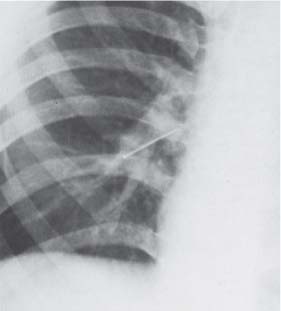

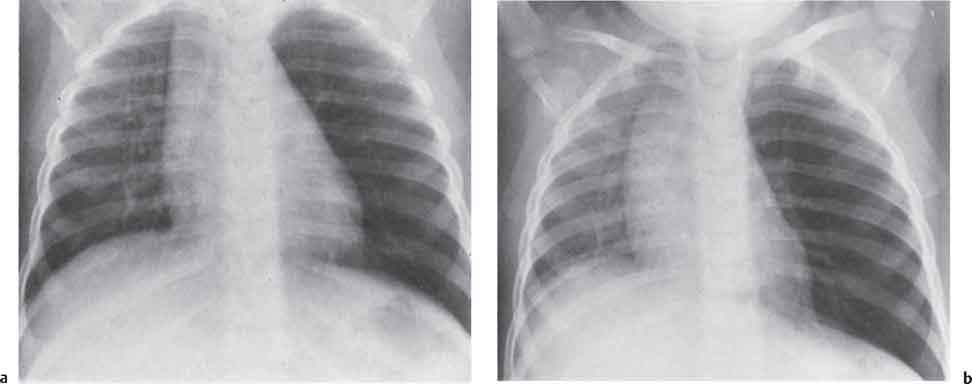

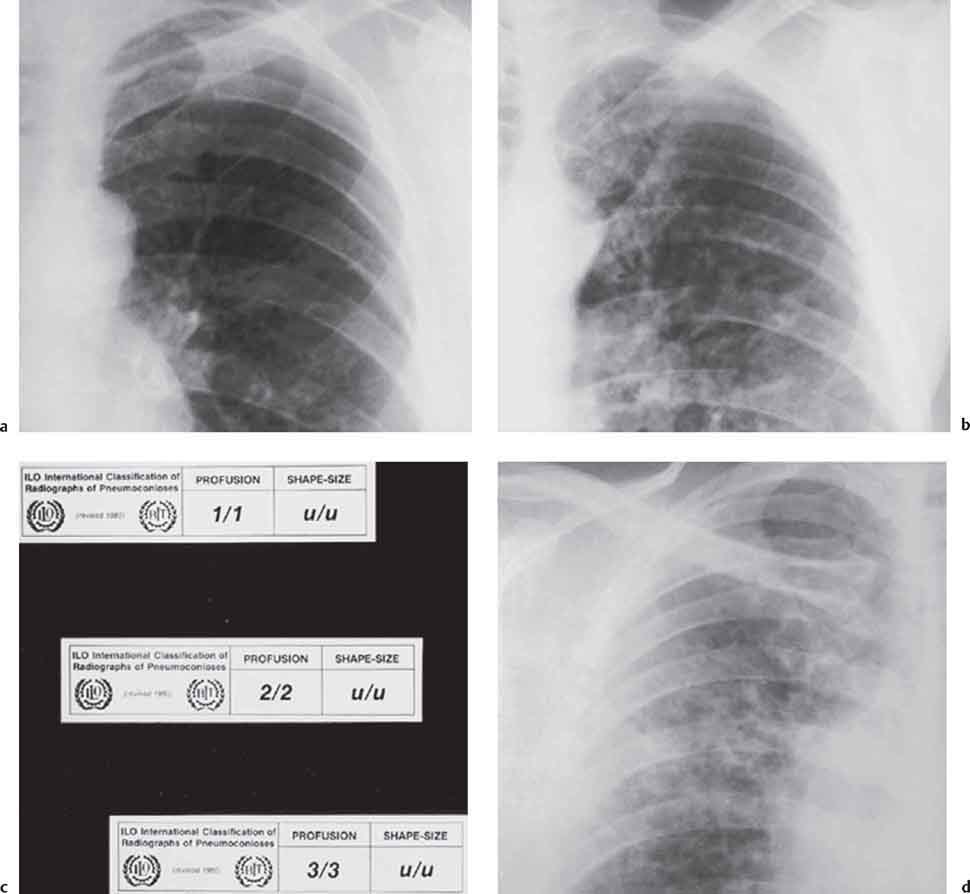

5 Inhalational Lung Diseases and Pneumoconioses Foreign body aspiration is typically seen in early childhood. Much less frequently, adults may inhale tooth fragments or dental fillings. Aspirated foreign bodies usually pass down the right main bronchus, which has a more vertical orientation than the left main bronchus. Radiographic features may indicate the presence and location of the foreign body (Figs. 5.1, 5.2). This can then be confirmed and removed at bronchoscopy or computed tomography (CT) may be performed prior to bronchoscopy. Aspiration material leads to tracheal/bronchial irritation with symptoms of cough and dyspnea. If the foreign body is not detected promptly, it becomes surrounded by fibrous tissue and patients then may be asymptomatic or have minimal symptoms for many years. Radiopaque foreign bodies such as coins, marbles, and teeth are visible on standard radiographs. Indirect signs indicating the presence of a nonopaque foreign body include: (Figs. 5.3 and 5.4): Fig. 5.1 Swallowed and aspirated teeth. Fig. 5.2 Aspirated pin. Fig. 5.3 Foreign body aspiration. Fig. 5.4a, b Check-valve obstruction in foreign body aspiration (a) with contralateral shift of the mediastinum to the right side in expiration (b). Helical CT will frequently allow direct visualization of the foreign body within the airway. Regional air trapping within the lung distal to the endobronchial body may be seen in cases of check-valve obstruction or atelectasis, and pneumonic consolidation may be present if the inhaled body leads to a high-grade obstruction. The pneumoconioses are a group of lung diseases caused by inhalation of inorganic or organic dust of animal or plant origin. Typically, chronic environmental or domestic exposure leads to disease after a variable number of years. Minute dust particles up to a maximum diameter of 10 µm reach the alveoli during inspiration. There they are phagocytosed by macrophages and are deposited in the lung parenchyma. Larger particles are retained in the upper respiratory tract and are cleared by the mucociliary escalator. In simple pneumoconiosis, the inhaled dust particles do not cause a reaction in the pulmonary parenchyma. Foreign body reactions, however, are frequent and result in eventual fibrosis. Dust particles may also bind with endogenous proteins; this complex then acts as an antigen and the resulting allergic inflammatory response may also progress to pulmonary fibrosis. Parenchymal fibrosis is characterized by cicatricial emphysema and a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function tests. An accompanying chronic bronchitis is frequent and results in a degree of obstructive ventilatory impairment. In addition, certain types of dust cause specific types of lung injury. For example, silicosis may be associated with tuberculous reactivation and asbestos exposure is associated with an increased risk of developing both bronchial carcinoma and mesothelioma. Pneumoconioses are recognized as occupational diseases if a probable link between the occupation and the illness can be established. This “probability” is based on the history of exposure, abnormal pulmonary function tests, and appropriate findings on imaging studies. Lung biopsy is rarely necessary. The International Labor Office has established standardized criteria for the classification of pneumoconioses based on the categorization of pulmonary opacities on the posteroanterior (PA) chest radiograph (ILO 2000): Table 5.1 Pneumoconioses due to inorganic dusts (from Mathys 2001) Fig. 5.5 Radiographic interpretation form based on the ILO Classification (see pp. 131–134 for coding and symbols). The ILO provides three guidelines for interpreting radiographic findings: Formal disability assessment by a specially trained and approved physician is based strictly on use of standard reference radiographs, computer-interpretable data sheets, and in some cases CT assessment. A simplified scheme based on overall impression of pulmonary involvement has been adopted for clinical use. The predominant type of opacity and the predominant grade of profusion are determined using the ILO verbal definitions. For example, grade qq 2/2 refers to numerous round opacities, 1.5–3 mm in diameter, scattered throughout both lungs but not obscuring pulmonary vascular markings; qt 2/2 refers to the additional presence of irregular opacities 1.5–3 mm in diameter. This simplified scheme by definition precludes a detailed account of all findings and, in particular, of regional variations in severity of change. Fig. 5.6 Illustrative radiographs from the ILO reference series. Fig. 5.7 Diagram illustrating pulmonary opacity codes used in the ILO Classification. RUZ = right upper zone (see pp. 131–134, Fig. 2.10).

Foreign Body Aspiration

Clinical Features

Radiologic Findings

Chest Radiograph

Computed Tomography

Pneumoconiosis

Pathology and International Labor Office (ILO) Classification

Syndrome

Source of antigen

Effects

Progressive pneumoconiosis due to silica-containing dusts, with relatively severe fibrosis:

Talcosis

Chalk (magnesium, silicate), industrial lubricants, rubber products. Inhalation of pure talc, talc in association with silica (talcosiliosis), and talc in association with asbestos fibers (talcoasbestosis).

1. Changes similar to asbestosis but with sparing of the apices and costophrenic angles. 2. Confluence of nodules to give PMF-type appearance. 3. Hilar lymph node enlargement.

Kaolinosis (kaolin lung)

Aluminum silicate, porcelain, and ceramic industries.

Fibrosis due to the presence of quartz dust in kaolin.

Persistent pneumoconioses due to quartz-free dusts, with mild fibrosis:

Anthracosis

Coal dust, coal mining, heaters.

No clinical effects or radiographic changes; black lungs seen at autopsy.

Siderosis

Iron oxide, arc welders, silver polishers, iron mining.

Inert deposits producing small opacities. Nodular opacification characteristically involving the midzones and reversible on cessation of exposure. Silicosiderosis: pulmonary fibrosis.

Bauxite lung

Aluminum manufacturing, smelting of aluminum ore to produce corundum.

Emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis.

Aluminum lung

Manufacture of explosives.

Fine reticular and focal opacities, spontaneous pneumothorax.

Berylliosis

Aircraft manufacturing.

Only 2% of exposed workers develop berylliosis; acute form manifest as alveolitis, chronic form is associated with generalized granulomatous disease similar to sarcoidosis.

Hard-metal lung disease

Tungsten, carbide, cobalt, titanium, vanadium, antimony, tin, steel tool manufacturing.

Spectrum of change from bronchitis and bronchiolitis through to subacute fibrosing alveolitis and giant cell interstitial pneumonia.

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine