11 Interventional techniques

Ultrasound-guided biopsy: general considerations

Methods of ultrasound guidance

Biopsy guidance

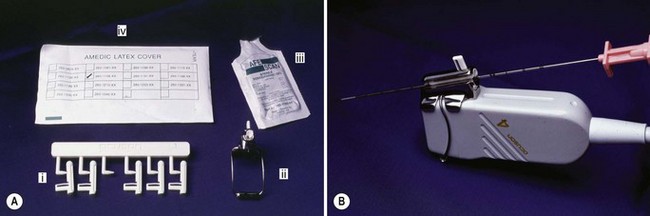

Most manufacturers provide a biopsy guide which fits snugly onto the transducer head and provides a rigid pathway for the needle (Fig. 11.1) These are now common and a widely accepted method of biopsy. The fixed biopsy guide contains a groove for a series of plastic inserts ranging from 14G to 22G size, depending upon the size of the biopsy needle. It is usual to use one size greater than the needle (i.e. a 16G insert for an 18G needle) as the needle tends to move more freely. The guide is sterilized and fitted onto the transducer over a sterile sheath.

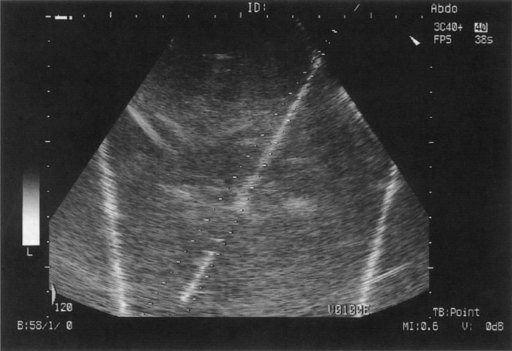

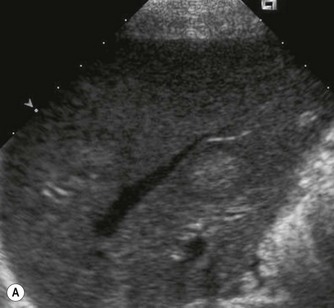

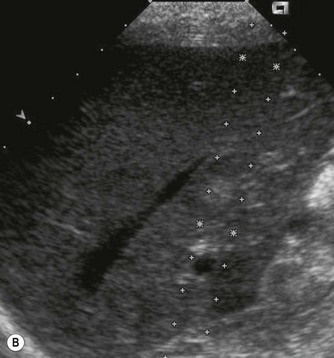

The needle pathway is displayed on the ultrasound monitor electronically – as a line or narrow sector – through which the needle passes. The operator then scans in order to align the electronic pathway along the chosen route, the needle inserted, and the biopsy taken. These attachments should be tested regularly to ensure the needle follows the correct path (Fig. 11.2).

Equipment and needles

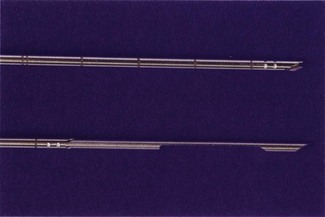

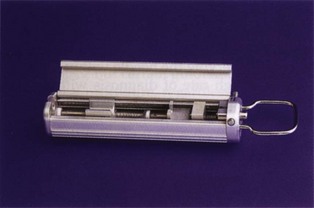

The core of tissue for histological analysis is obtained with a specially designed needle consisting of an inner needle with a chamber or recess for the tissue sample and an outer, cutting needle which moves over it i.e. the Tru-cut needle. The biopsy is obtained in two stages – first the inner needle is advanced into the tissue, then the outer cutting sheath is advanced over it and the needle withdrawn containing the required tissue core (Fig. 11.3). The use of a spring-loaded ‘gun’ to operate these needles is now commonplace (Fig. 11.4). It is designed to enable operation of the needle with one hand, (whilst being able to hold the probe with the other) and has the advantage of being sterile and disposable.

The whole needle is advanced into the tissue, just in front of the area to be biopsied. By pressing the spring-loaded control, the inner part is quickly advanced into the lesion, followed rapidly by the cutting sheath over it. Needles can be obtained in a variety of sizes, generally 14, 16, 18 or 20G. Most focal lesions are biopsied with a standard 18G needle. As a general principle, as the needle advances approximately 1.5–2.0 cm during biopsy, it is advisable to position the needle tip on the edge of a lesion to obtain a good histological sample as most lesion necrosis tends to be centrally located. Because the gun enables the operator to scan with one hand and biopsy with the other, the needle can be observed within the lesion, yielding a high rate of diagnosis with a single pass technique,1 and minimizing post-biopsy complications.

Ultrasound-guided biopsy procedures

Liver biopsy

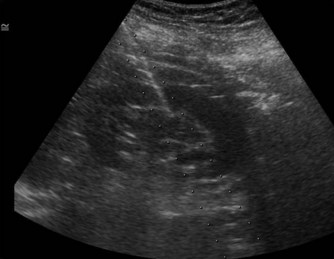

The most common reason for ultrasound-guided biopsy is for metastatic disease. The liver is one of the most common sites for metastases and histology may be required to confirm the diagnosis, or, more usually, to identify the origin of an unknown primary lesion (Figs 11.5–11.7). Biopsy of suspected HCCs is generally avoided, as it is associated with a poorer treatment outcome and there is a small risk of tumour seeding. CEUS and/or MRI can now characterize many lesions, avoiding the need for biopsy in an increasing number of cases. Focal lesion biopsy is generally safely and accurately performed with an 18G needle which yields reliable tissue for histological analysis. In general, an accuracy of 96% should be achievable.2

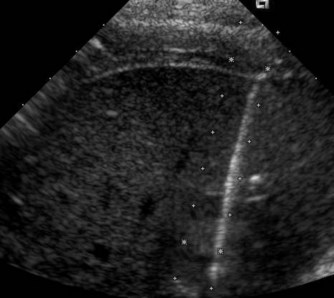

Fig. 11.6 • The needle is introduced into the liver, just in front of the lesion under ultrasound guidance.

Where coagulation profiles are not correctable (and most generally are) liver biopsy can be performed using a ‘plugged’ technique or, more commonly, by the transjugular route (Fig. 11.8).

Pancreatic biopsy

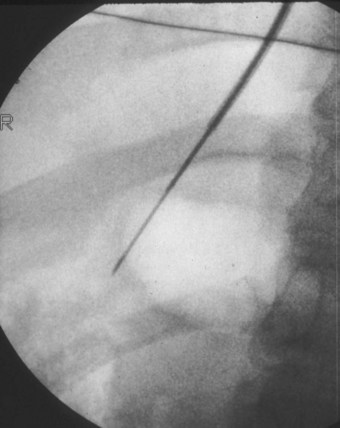

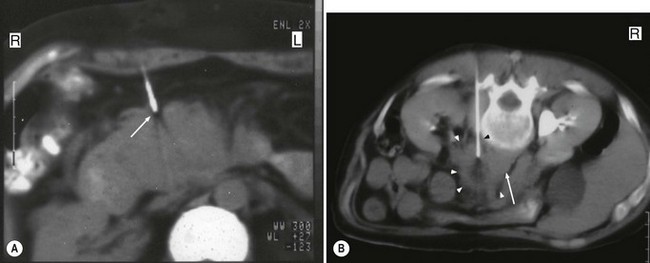

The commonest reason for biopsy of the pancreas is in patients presenting with obstructive jaundice due to a mass in the head of the gland. A fine needle technique enables the mass to be accessed through the stomach and left lobe of liver without complications, however, an 18G needle biopsy is advisable to try to reduce false-negative results due to the well-known situation of a carcinoma being associated with an element of peripheral inflammation. Pancreatic biopsies are often better performed under CT control (Fig. 11.9) particularly when lesions are small, patients big and/or the lesion is difficult to identify with ultrasound. In those patients with negative biopsies very often interval CT scans are performed to see if the lesion is static or progressive.

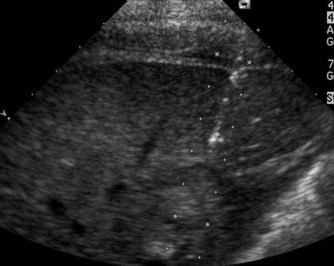

Native kidney biopsy

The patient’s cooperation is required in suspending respiration at the crucial moment. This avoids undue damage to the kidney as the needle is introduced through the capsule. The needle should be positioned just within the capsule prior to biopsy so that the maximum amount of cortical tissue is obtained for analysis as the throw of the needle may be up to 2 cm (Fig. 11.10).

Renal transplant biopsy

Biopsy is a valuable tool in the post-operative management of a transplant recipient (Chapter 7), enabling the cause of graft dysfunction to be identified, in particular differentiating acute tubular necrosis from acute rejection. Ultrasound guidance is essential in order to reduce complications such as haematoma, vascular damage (which may result in an AV fistula or pseudoaneurysm formation) and laceration of the renal collecting system.

A single pass technique, using the spring-loaded biopsy gun with an 18G needle is usually sufficient for histological purposes, however two passes may be required so that electron microscopy and immunofluorescence can also be performed. The procedure is well tolerated by the patient and the complication rate low at less than 5%.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree