4 Pathology of the liver and portal venous system

Focal liver lesions

The ‘mass effect’

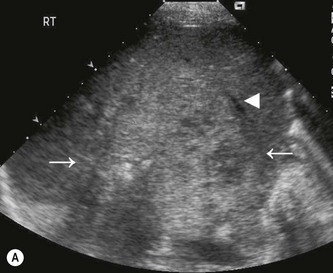

Masses that are large and/or closely adjacent to a vessel demonstrate the effect more readily. The mass effect does not, of course, differentiate benign from malignant masses, or help in any way to characterize the mass. It is particularly useful when the mass is isoechoic compared with normal liver (see Fig. 4.15 below). In such cases, the effect of the mass on adjacent structures may be the main clue to its presence.

Benign focal liver lesions

Simple cysts

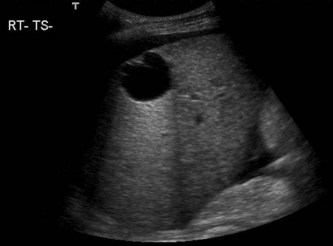

The simple cyst has three acoustic properties, which are pathognomonic: it is anechoic, has a well-defined smooth capsule and exhibits posterior enhancement (increased through-transmission of sound) (Fig. 4.1). Although theoretically it is possible to confuse a simple cyst with a choledochal cyst (see Chapter 3), the latter’s connection to the biliary tree is usually demonstrable on ultrasound. A radioisotope HIDA scan will confirm the biliary connection if doubt exists.

Complex cysts

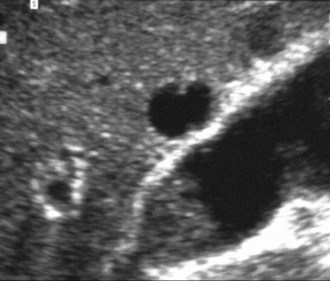

Some cysts may contain a thin septum, which is not a significant finding. Occasionally haemorrhage or infection may occur in a simple cyst, giving rise to low level, fine echoes within it (Fig. 4.2). Such cysts are usually treated conservatively although the larger ones may be monitored with ultrasound, particularly if symptomatic. Percutaneous aspiration of larger cysts under ultrasound guidance may afford temporary decompression but is rarely performed, as they invariably recur, and there is a risk of infection. Laparoscopic fenestration (deroofing) in which part of the cyst wall is removed allowing drainage, provides a more permanent solution to large, symptomatic cysts.1

A rare cause of a cystic lesion in the liver is the cystadenoma – a benign epithelial tumour which may appear uni- or multilocular. These have a pre-malignant potential, rarely progressing to form a cystadenocarcinoma. Close monitoring with ultrasound will demonstrate gradual increase in size, changes in the appearances of the wall of the cyst, such as thickening or papillary projections, and internal echoes in some cases, which may indicate malignant change. Cystic malignant liver lesions are uncommon, and the majority represent necrotic metastases, but it is extremely important to recognize suspicious malignant features such as solid nodules or thickened walls and septations (Fig. 4.3). A diagnostic aspiration may be performed under ultrasound guidance, and the fluid may contain elevated levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) if malignant.2 Cystadenomas are usually surgically removed due to their malignant potential (Fig. 4.4).

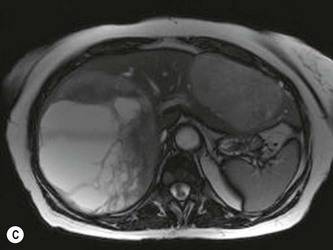

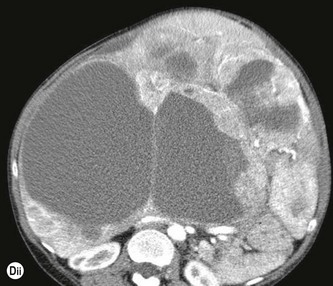

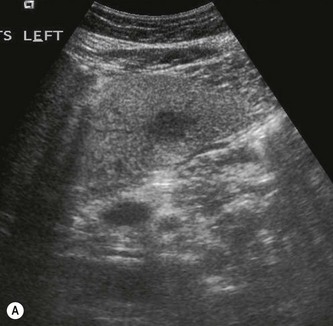

Polycystic liver

There is a fine dividing line between a liver that contains multiple simple cysts and ‘polycystic liver disease’. The latter usually occurs with polycystic kidneys, a common autosomal dominant condition readily recognizable on ultrasound (see Chapter 7), but rarely may affect the liver alone, sparing the kidneys (Fig. 4.5). The appearances are of multiple, often septated cysts, of varying sizes throughout the liver. The cumulative enhancement behind the numerous cysts imparts a highly irregular echogenicity to the liver texture and may make it extremely difficult to pick up other focal lesions which may be present.

Fig. 4.5 • Multiple cysts enlarging the left lobe of liver in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

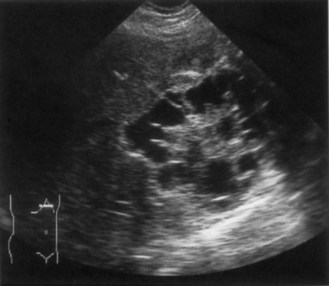

Hydatid (echinococcal) cyst

Ultrasound may demonstrate a spectrum of appearances, from cystic through to solid, and the diagnosis can be made by looking carefully at the wall and contents; the hydatid cyst has two layers to its capsule, which may appear thickened, separated or detached on ultrasound. Daughter cysts may arise from the inner capsule – the honeycomb or cartwheel appearance (Fig. 4.6) and the cyst may contain floating membranes and fine sand or debris.3 A calcified rind around a cyst is usually associated with an old, inactive hydatid lesion.

The diagnosis of hydatid, as opposed to a simple cyst, is an important one, as any attempted aspiration may spread the parasite further by seeding along the needle track if the operator is unaware of the diagnosis. Hydatids may be treated successfully using percutaneous ultrasound guided aspiration with sclerotherapy although surgical resection is necessary for some cases.4

Abscesses

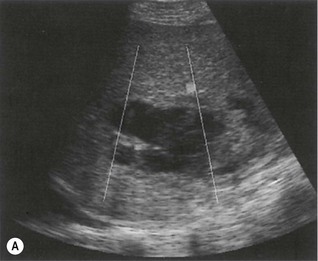

Ultrasound appearances

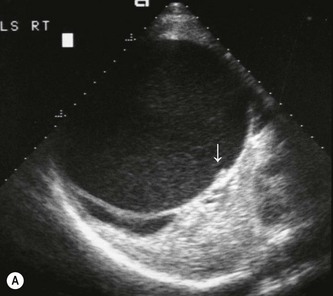

Hepatic abscesses may display a spectrum of acoustic features. Their internal appearances vary considerably; in the very early stages there is a zone of infected, oedematous liver tissue which appears on ultrasound as a hypoechoic, solid focal lesion. As the infection develops, the liver tissue becomes necrotic and liquefaction takes place. The abscess may still appear full of homogeneous echoes from pus and can be mistaken for a solid lesion, but as it progresses, the fluid content may become apparent, usually with considerable debris within it. Because they are fluid-filled, abscesses demonstrate posterior enhancement (Fig. 4.7A). The margins of an abscess are irregular, often ill-defined and frequently thickened. The inflammatory capsule of the abscess may demonstrate vascularity on colour or power Doppler, but this is not invariable, and depends on equipment sensitivity and size of the lesion. Infection with gas-forming organisms may account for the presence of gas within some liver abscesses (Fig. 4.7B).

(C) A percutaneous drain put into a liver abscess under ultrasound guidance.

(D) A resolving abscess (arrows) demonstrates calcification, with no liquefied content.

(E) Two abscesses in a patient on immunosuppression.

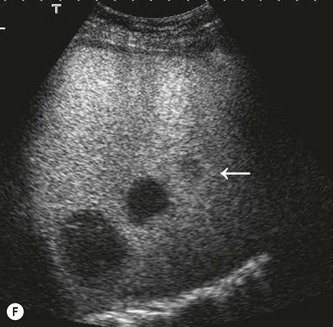

(F) CEUS of the case in E demonstrates a third smaller abscess (arrow) not visible pre-contrast.

There are three main types of abscess.

Pyogenic abscess

Pyogenic abscesses are frequently multiple, and the patient must be closely monitored after diagnosis to prevent rapid spread. They are still considered a lethal problem, which has increased in recent years due to increasingly aggressive surgical approaches to many abdominal neoplasms.5

Amoebic abscess

This is a parasitic infection which is rare in the UK, but found frequently in parts of Africa, India and the southern parts of the USA. Increasing worldwide travel means a more frequent recognition of such lesions with ultrasound,6 and suspicion should be raised when the patient has visited these countries. It is usually contracted by drinking contaminated water and infects the colon, ulcerating the wall and subsequently being transported to the liver via the portal venous system.

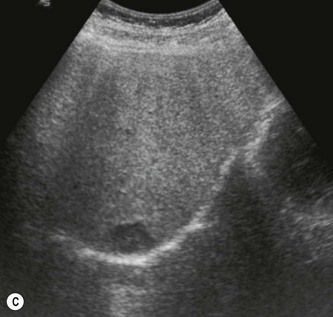

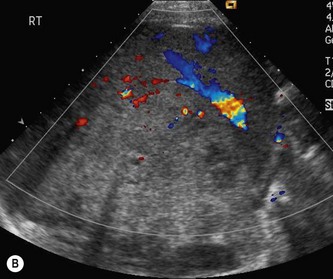

Haematoma

A haematoma is the result of trauma (usually, therefore, via the emergency department) but the trauma may also be iatrogenic, e.g. following a biopsy procedure (hence the value of using ultrasound guidance to avoid major vessels in the liver) or surgery. The liver haematoma may have similar acoustic appearances to those of an abscess but does not share the same clinical features or history (Fig. 4.8).

The acoustic appearances depend upon the timing – a fresh haematoma may appear liquid and hypoechoic, but rapidly becomes more ‘solid’ looking and hyperechoic, as the blood clots. As it resolves the haematoma liquefies and may contain fibrin strands. It will invariably demonstrate a band of posterior enhancement and has irregular, ill-defined walls in the early stages. Later on it may encapsulate, leaving a permanent cystic ‘space’ in the liver, and the capsule may calcify. Injury to the more peripheral regions may cause a subcapsular haematoma which demonstrates the same acoustic properties. The haematoma outlines the surface of the liver and the capsule can be seen surrounding it. This may be the cause of a palpable ‘enlarged’ liver (Fig. 4.8B).

Intervention is rarely necessary and monitoring with ultrasound confirms eventual resolution. More serious hepatic ruptures, however, causing haemoperitoneum, may require surgery. CEUS is useful in demonstrating the extent of injury and is particularly useful in the absence of a haemoperitoneum (see Chapter 10, Fig. 10.1) (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Cystic focal liver lesions – differential diagnoses

| SIMPLE CYST | |

| Anechoic, thin capsule, posterior enhancement (may contain thin septae) | Common finding, usually insignificant |

| Consider polycystic disease if multiple (rarely an AV malformation may mimic a septated cyst – exclude by using colour Doppler) | |

| COMPLEX CYST | |

| Thin capsule + internal echoes | Haemorrhage or infection in a cyst |

| Mucinous metastasis | |

| Cystadenoma | |

| Capsule thickened or complex, may also contain echoes | Hydatid cyst |

| Cystadenocarcinoma | |

| Intrahepatic pancreatic pseudocyst (rare) | |

| SOLID/CYSTIC LESION | |

| Irregular margin, internal echoes + debris/solid material | Abscess |

| Haematoma | |

| Necrotic metastasis | |

| Cavernous haemangioma |

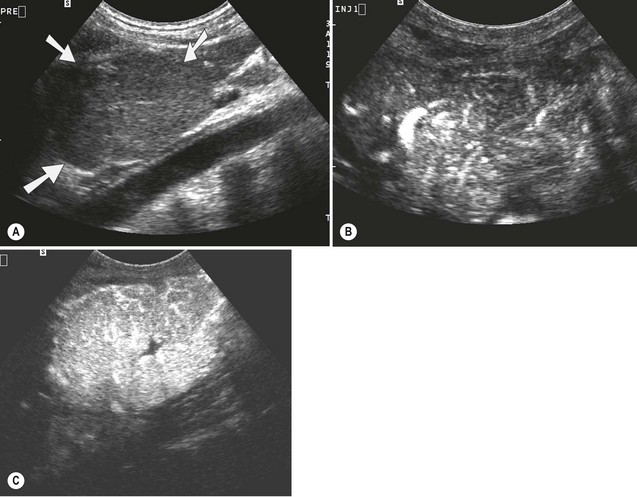

Haemangioma

Their acoustic appearances vary; the majority are hyperechoic, rounded well-defined lesions, but they may also be hypoechoic or of mixed echogenicity. In patients with fatty livers, the haemangioma frequently looks hypoechoic relative to the background of the hyperechoic hepatic parenchyma. Larger ones can demonstrate a spectrum of reflectivity depending on their composition, and may demonstrate pools of blood and central areas of degeneration. They frequently exhibit slightly increased through-transmission, with posterior enhancement, particularly if large. This is probably due to the increased blood content compared with the surrounding liver parenchyma (Fig. 4.9).

As with many lesions, colour or power Doppler is too insensitive to pick up the slow flow in haemangiomas or to assist with lesion characterization. Microbubble contrast agents demonstrate a peripheral, globular enhancement with gradual centripetal filling to become isoechoic with the background liver in the sinusoidal phase.7 CEUS frequently provides a definitive diagnosis at the time of scanning, reassuring the patient and obviating the need for further imaging of follow-up (Fig. 4.9).

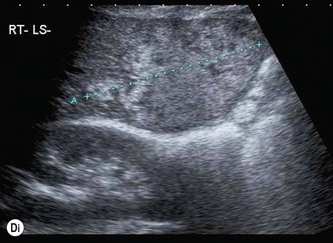

Focal nodular hyperplasia

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is the second most common solid, benign liver tumour. It is made up of a hyperplastic proliferation of liver cells with hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, biliary and fibrous elements. It is most commonly found in young women, and is usually discovered by chance, being asymptomatic. Its ultrasound characteristics vary, from hypo-, iso- to hyperechoic compared with background liver (Fig. 4.10) and it may be multifocal. As with the haemangioma, it presents a diagnostic dilemma when found on CT or ultrasound, as its characteristics vary. As with haemangioma, CEUS is extremely helpful in characterizing incidental FNH, as it usually displays rapid arterial stellate filling, followed by centripetal enhancement with contrast uptake isoechoic with background liver in the sinusoidal phase.8 It may, however, be difficult to differentiate from the rarer adenoma which also exhibits rapid arterialization on CEUS.9

Fig. 4.10 • FNH:

(A) In the left lobe (arrows). These are frequently almost isoechoic with normal liver tissue.

(C) The same lesion seconds later, showing a central scar.

(E) Another example of an FNH, almost isoechoic with background liver.

Adenoma

The hepatic adenoma is a benign focal lesion consisting of a cluster of atypical liver cells (Fig. 4.11). Within this, there may be pools of bile or focal areas of haemorrhage or necrosis. This gives rise to a heterogeneous, patchy echotexture. The smaller ones tend to be homogeneous with a smooth texture. Their lipid content causes a tendency to be hyperechoic, although usually less reflective than a haemangioma, and many have similar reflectivity to the surrounding liver parenchyma.

Fig. 4.11 • (A) Adenoma in segment V of the liver in a young woman on the contraceptive pill.

(B) An unusual example of cystic degeneration in a large adenoma.

Clinical features

They may cause pain, particularly if they haemorrhage, and may be palpable. If present during pregnancy, they can enlarge and rupture under the influence of oestrogen. In rare cases malignant transformation may occur10 so surgical removal is the management of choice, although occasionally some adenomas regress if the oral contraceptive is discontinued.

Focal fatty change

Focal fatty infiltration

The deposition of fat confined to certain focal areas of the liver is related to the blood supply to that area. Fatty infiltration increases the reflectivity of the parenchyma, making it hyperechoic. This can simulate a focal mass, such as a metastasis. Unlike a focal lesion however, it does not display any mass effect and the course of related vessels remains constant. It tends to have a characteristic straight-edged shape, rectangular or ovoid, corresponding to the region of local blood supply (Fig. 4.12). Foci of fatty change may be multiple, or may affect isolated liver segments. The most common sites are in segment IV around the porta, in the caudate lobe (segment I) and in the posterior area of the left lobe (segment III).

Fig. 4.12 • (A) Focal fatty change (arrow) can mimic a focal lesion.

(B) Focal fatty sparing in a characteristic position just anterior to the gallbladder.

CEUS is useful and accurate in differentiating focal fatty change from a true lesion, as the contrast uptake is identical to background liver, and the contrast convincingly demonstrates the lack of mass effect (Fig. 4.12D) This technique usually obviates the need for further imaging in focal fatty change.

Focal fatty sparing

The reverse process may also occur, in which a diffusely fatty, hyperechogenic liver has an area which has been spared from fat deposition due to its blood supply. This area is less reflective than the surrounding liver and may mimic a hypoechoic neoplastic lesion, but as with focal fatty infiltration, it has regular outlines and shape and no mass effect. The most common sites for fatty sparing are similar to those for focal fatty infiltration; segment IV just anterior to the portal vein or gallbladder (Fig. 4.12B), segment I (the caudate lobe) and around the gallbladder fossa.

Unlike a true focal lesion, fatty change does not exhibit a mass effect, and normal, undisplaced vasculature can be demonstrated with colour Doppler (in the larger areas) or contrast ultrasound (particularly useful for the smaller focal areas) in both of focal fatty infiltration and fatty sparing (see also Fig. 4.19C).

Granuloma

Granulomas are benign liver masses which are associated with chronic inflammatory liver diseases. They have a particular association with primary biliary cirrhosis, sarcoidosis or tuberculosis. They may be multiple and small, in which case the liver often looks coarse and hyperechoic. More often they are small discrete lesions which may be hypo- or isoechoic, sometimes with a hypoechoic rim like a target, or calcified with distal shadowing (Fig. 4.13). They can undergo central necrosis.

Hepatic calcification

Calcification occurs in the liver as a result of some pathological processes, and may be seen following infection or parasitic infestation. It may be focal – usually the end stage of a previous abscess, haematoma or granuloma – which usually indicates that the lesion in question is no longer active. It may also be seen within some metastases. Calcification may also be linear in nature, following the course of the portal tracts. This can be associated with old tuberculosis or other previous parasitic infestations such as schistosomiasis11 (Fig. 4.14).

Fig. 4.14 • Considerable deposits of calcification are seen in the liver in this patient with nephrotic syndrome.

Calcification, which casts a strong and definite shadow should be distinguished from air in the biliary tree (Fig. 3.46), which casts a reverberative shadow and is usually associated with previous biliary interventions, such as ERCP, sphincterotomy or stent placement.

Malignant focal liver lesions

Metastases

The liver is one of the most common sites to which malignant tumours metastasize. Secondary deposits are usually bloodborne, spreading to the liver via the portal venous system (e.g. in the case of gastrointestinal malignancies) or hepatic artery (e.g. lung or breast primaries,) or spread via the lymphatic system. Some spread along the peritoneal surfaces – for example ovarian carcinoma. This demonstrates an initial invasion of the subserosal surfaces of the liver (see Fig. 4.16A below), as opposed to the more central distribution seen with a haematogenous spread (see Fig. 4.16B below). The former, peripheral pattern is more easily missed on ultrasound because small deposits are often obscured by near-field artefact or rib shadows. It is therefore advisable for the operator to be aware of the possible pattern of spread when searching for liver metastases.

Ultrasound appearances

The acoustic appearances of liver secondaries are extremely variable (Figs 4.15, 4.16). When compared with normal surrounding liver parenchyma, metastases may be hyperechoic, hypoechoic, isoechoic or of mixed pattern. It is not possible to characterize the primary source by the acoustic properties of the metastases.

Fig. 4.15 • The mass effect

(A) A large isoechoic lesion (arrows), displaces the middle hepatic vein (arrowhead).

Fig. 4.16 • Examples of liver metastases:

(B) Bloodborne metastases from bowel carcinoma are distributed throughout the liver.

(E) A necrotic metastasis, demonstrating posterior acoustic enhancement.

(F) Calcified metastases from breast carcinoma.

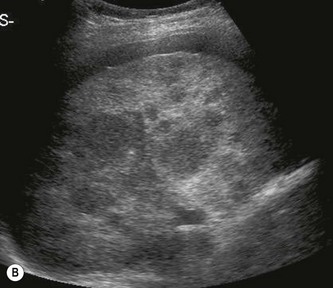

Metastases tend to be solid with ill-defined margins. Some metastases, particularly the larger ones, contain fluid as a result of central necrosis (Fig. 4.16E), or because they contain mucin, for example from some ovarian primaries. Occasionally, calcification is seen within a deposit, causing distal acoustic shadowing, and this may also develop following treatment with chemotherapy. In some diseases, for example lymphoma, the metastases may be multiple but tiny – not immediately obvious to the operator as discrete focal lesions but as a coarse-textured liver (Fig. 4.16F). This type of appearance is non-specific and could be associated with a number of conditions, both benign and malignant.

Doppler is unhelpful in characterizing liver metastases, most of which appear poorly vascular or avascular. Fundamental non-contrast ultrasound lacks sensitivity in the diagnosis of liver metastases, as many lesions are either isoechoic, or small (subcentimetre) rendering them almost invisible. The use of microbubble contrast agents radically improves both the characterization and detection of metastatic deposits on ultrasound.12 The injection of a bolus of contrast agent when viewed using pulse-inversion demonstrates variable vascular phase enhancement in the arterial and portal phases, but the sinusoidal phase invariably lacks contrast uptake (Fig. 4.16G, H). This is a particularly useful technique as it increases the contrast resolution between metastasis and background liver, meaning that even subcentimetre lesions are reliably demonstrated.

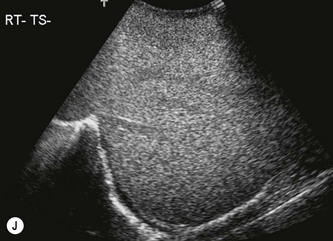

CEUS also increases the operator’s confidence in the absence of metastases, particularly in cases with altered LFTs and prior history of malignancy (Fig. 4.16J). This is useful in obviating the need for further imaging in normal livers.

Clinical features and management

Ultrasound-guided biopsy may be useful in diagnosing the primary and complements further imaging such as X-rays and contrast bowel studies. Accurate staging of the disease is performed with CT, MRI and/or PET-CT,13 which have improved sensitivity for identifying extrahepatic and systemic disease, such as peritoneal deposits and lymphadenopathy, and which can more accurately demonstrate adjacent spread of primary disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree