7 Ultrasound of the renal tract

The normal renal tract

Ultrasound technique

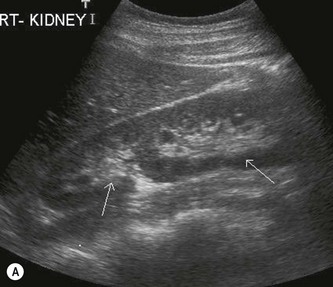

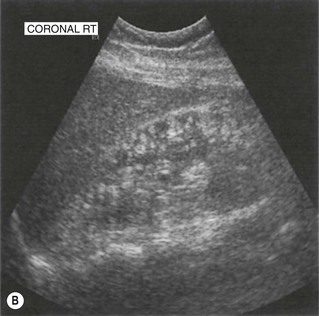

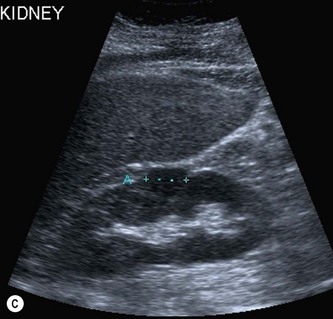

The right kidney is readily demonstrated through the right lobe of the liver. Generally a subcostal approach displays the (more anterior) lower pole to best effect, while an intercostal approach is best for demonstrating the upper pole (Fig. 7.1). The left kidney (LK) is not usually demonstrable in a true sagittal plane because it lies posterior to the stomach and splenic flexure. The spleen can be used as an acoustic window to the upper pole by scanning coronally, from the patient’s left side, with the patient supine or decubitus (left side raised) but, unless the spleen is enlarged, the lower pole must usually be imaged from the left side posteriorly. Coronal sections of both kidneys are particularly useful as they display the renal pelvicalyceal system and its relationship to the renal hilum (Fig. 7.1C). This section demonstrates the main blood vessels and ureter (if dilated). As with any other organ, the kidneys must be examined in both longitudinal and transverse (axial) planes and the operator must be flexible in his/her approach to obtain the necessary results.

Normal ultrasound appearances of the kidneys

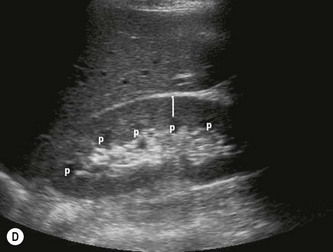

The cortex of the normal kidney is slightly hypoechoic when compared to the adjacent liver parenchyma, although this is age dependent. In young people it may be of similar echogenicity and in the elderly it is not unusual for it to be comparatively hyperechoic and thinner. The medullary pyramids are seen as regularly spaced, hypoechoic (not echo-free) triangular structures between the cortex and the renal sinus (Fig. 7.1). The tiny reflective structures often seen at the margins of the pyramids are echoes from the arcuate arteries which branch around the pyramids.

The kidney develops in the fetus from a number of lobes that fuse together. Occasionally the traces of these lobes can be seen on the surface of the kidney, forming fetal lobulations (Fig. 7.2A); these may persist into adulthood. The issue for the sonographer is being able to recognise these as normal variations, as distinct from a renal mass, or renal scarring.

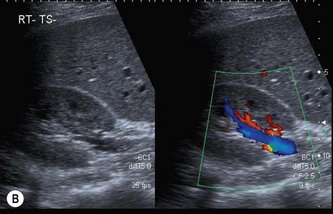

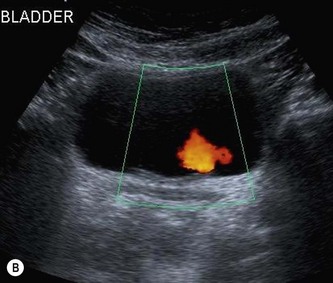

Normal ultrasound appearances of the lower renal tract

When the bladder is distended with urine, the walls are thin, regular and hyperechoic. The walls may appear thickened or trabeculated if the bladder is insufficiently distended, making it difficult to exclude a bladder lesion. The ureteric orifices can be demonstrated in a transverse section at the bladder base. Ureteric jets can easily be demonstrated with colour Doppler at this point and normally occur between 1.5 and 12.4 times per minute (a mean of 5.4 jets per minute) from each side (Fig. 7.2B).1

It is useful to examine the pelvis for other masses, e.g. related to the uterus or ovaries, which could exert pressure on the ureters causing proximal dilatation. The prostate is demonstrated transabdominally by angling caudally through the full bladder (Fig 7.2C). The investigation of choice for the prostate is transrectal ultrasound, however, an approximate idea of its size can be gained from transabdominal scanning.

Measurements

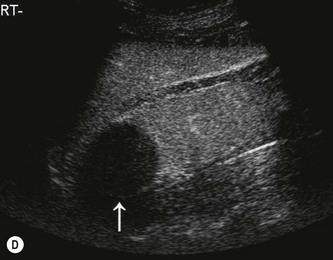

The cortical thickness of the kidney is generally taken as the distance between the capsule and the margin of the medullary pyramid (Fig. 7.1D). This varies between individuals and within individual kidneys, and tends to decrease with age.

Haemodynamics

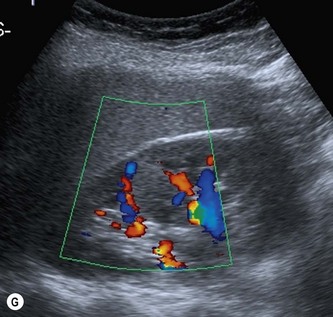

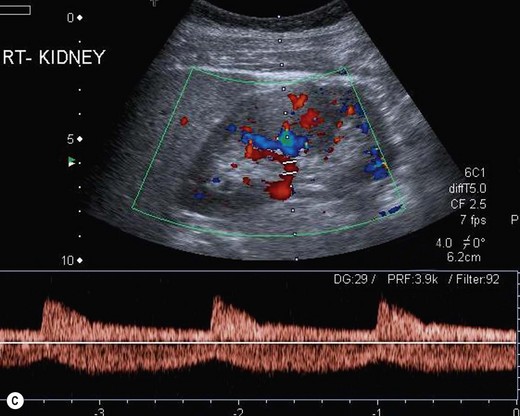

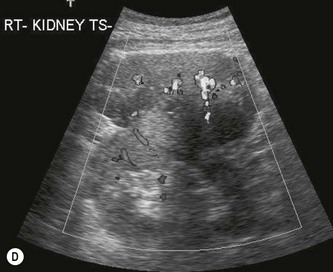

The vascular tree of the kidney can be effectively demonstrated with colour Doppler (Fig. 7.3). By manipulating the system sensitivity and using a low PRF, small vessels can be demonstrated at the periphery of the kidney.

Fig. 7.3 • (A) Colour Doppler of the RK demonstrating normal intrarenal perfusion throughout the kidney.

(B) Power Doppler demonstrating renal perfusion.

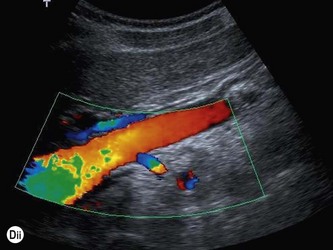

(Dii) The LRA appears in blue as it is flowing away from the transducer.

Demonstration of the extrarenal main artery and vein with colour Doppler is most successful in the coronal or axial section by identifying the renal hilum and tracing the artery back to the aorta or the vein to the IVC. The best Doppler signals – i.e. the highest Doppler shift frequencies – are obtained when the direction of the vessel is parallel to the beam, and taken on suspended respiration. The LRV is readily demonstrated between the SMA and aorta by scanning just below the body of the pancreas in transverse section. The origins of the renal arteries may be seen arising from the aorta in a coronal section (Fig. 7.3D).

The normal adult renal vasculature is of low resistance with a fast, almost vertical systolic upstroke and continuous forward end diastolic flow. Resistance generally increases with age.2 The more peripheral arteries are of lower velocity with weaker Doppler signals, and are less pulsatile than the main vessel.

Renal anatomical variants

Duplex kidney

This term is used to describe a spectrum of possible appearances, from two separate kidneys with separate collecting systems and duplex ureters, to a more simple division of the pelvicalyceal system at the renal hilum (Fig. 7.4A). The latter is more difficult to recognize on ultrasound, but the two moieties of the pelvicalyceal system are separated by a zone of normal renal cortex which invaginates the kidney – a hypertrophied column of Bertin (see below).

Duplex kidney is the most common congenital renal abnormality. It may be associated with other anomalies such as reflux, ectopic ureteric orifice or ureterocele, and may predispose the patient to infection or obstruction of the upper moiety or, rarely, the lower moiety.3 The main issue for the sonographer here is that one moiety may be mistaken on ultrasound for the entire kidney, especially if bowel gas overlies part of the kidney, and the operator must ensure that both renal poles are properly demonstrated. A chronically obstructed moiety in an adult patient may masquerade as a renal cyst or as fluid-filled bowel.

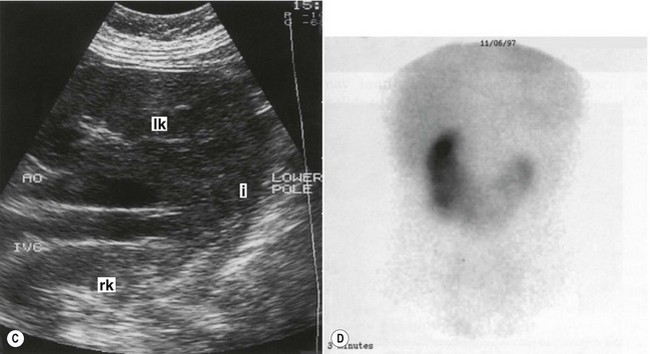

Horseshoe kidneys

In the horseshoe kidney, the kidneys lie one on each side of the abdomen but their lower poles are fused by a connecting band of renal tissue, or isthmus, which lies anterior to the aorta and IVC (Fig. 7.4B–D). The kidneys tend to be rotated and lie with their lower poles medially.

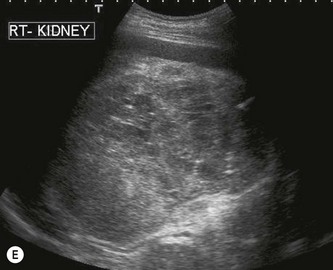

Extrarenal pelvis

Not infrequently, the renal pelvis projects outside the kidney, medial to the renal sinus. This is best seen in a transverse section through the renal hilum. It is frequently ‘baggy’ containing anechoic urine, which is prominently demonstrated on the ultrasound scan (Fig. 7.4E). The importance of recognizing the extra-renal pelvis lies in not confusing it with dilatation of the PCS, or with a para-pelvic cyst or collection.

Hypertrophied column of Bertin

The septum of Bertin is an invagination of renal cortex down to the renal sinus. It occurs at the junctions of original fetal lobulations and is present in Duplex systems, (see above) dividing the two moieties. Particularly prominent, hypertrophied columns of Bertin may mimic a renal tumour. It is usually possible to distinguish between the two as the column of Bertin does not affect the renal outline and has the same acoustic characteristics as the adjacent cortex (Fig. 7.4F, G).

Colour or power Doppler are helpful in revealing the normal, regular vascular pattern (as opposed to the chaotic and increased blood flow pattern of malignant renal tumours). If doubt persists, particularly in a symptomatic patient, CEUS reliably differentiates a prominent column of Bertin from tumour.4 An isotope scan can also be helpful demonstrating normally functioning renal tissue.

Renal cysts and cystic disease

Cysts

Ultrasound appearances

Like cysts in any other organ, they must display three basic characteristics – anechoic, a thin, well-defined capsule and exhibit posterior enhancement – if they are to be legitimately called ‘simple’. It can be difficult to appreciate the posterior enhancement if the hyperechoic perirenal fat lies distal to the cyst; scanning from a different angle (Fig. 7.5) is helpful.

Whilst a solitary, simple cyst can almost certainly be ignored, cysts with more complex acoustic characteristics may require further investigation, e.g. CT. A calcified wall may be associated with malignancy. Increasingly small renal cysts are incidentally discovered on ultrasound due to improved technology and they are by no means always simple. In 1989 Bosniak5 proposed a classification of cysts to be used with CT to differentiate benign from malignant lesions (Fig. 7.5B, C; Table 7.1). This has been used over the years in conjunction with ultrasound findings in order to highlight possible malignancy. Whilst it broadly works, it is by no means a definitive test6 and complex renal cysts should normally be monitored or undergo CT to evaluate further.

Table 7.1 Bosniak renal cyst classification for CT5

| CATEGORY | FEATURES |

|---|---|

| I | Benign simple cyst, thin walled, no septae, calcification or solid components. No contrast enhancement with CT |

| II | May contain hairline septae, possible fine calcification in the wall. Sharp margins. Benign |

| IIF | More hairline septae. Minimal thickening of septa or wall. May contain nodular calcification. No contrast enhancement of any soft tissue elements. Well marginated. Usually benign |

| III | Indeterminate cystic mass with thickened irregular wall or septa in which enhancement can be seen |

| 1V | Clearly malignant, containing enhancing soft tissue components |

These lesions can now be successfully characterized into the Bosniak classification using CEUS7 (see also Fig. 7.10.) CEUS is able to differentiate the vascularized solid components of complex renal masses at least as well as CT, and can also be used to monitor lesions, thereby reducing the radiation dose from CT.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

Ultrasound appearances

The disease is always bilateral, causing progressively enlarging kidneys with multiple cysts of various sizes, many having irregular margins (Fig. 7.6). There may be little or no demonstrable normal renal tissue and the kidneys may become so large that they visibly distend the abdomen.

APKD predisposes the patient to urinary tract infections, stones and cyst haemorrhage. The liver, spleen and pancreas should also be examined on ultrasound for associated cysts. Although there have been reports of an increased incidence of RCC in APKD, there is no substantial evidence for this and it is generally considered that the risk of RCC is the same as the general population.8,9

Tuberose sclerosis

Tuberose sclerosis is a rare, multisystem disorder with a wide spectrum of possible presentation. Up to 75% of patients may develop multiple renal cysts and/or multiple angiomyolipomas (AMLs).10 Rarely, renal cell carcinoma may occur, although it is thought that the occurrence is similar to that of the general population. However, RCC tends to occur at a younger age in patients with TS (see Fig. 7.8B).

Acquired cystic disease

Multiple cysts form in the kidneys, which may, like autosomal dominant PCKD, haemorrhage or become infected. The disease tends to be more severe the longer the patient has been on dialysis. The proliferative changes which cause acquired cystic disease also give rise to small adenomata and the ultrasound appearances maybe a combination of cysts and solid, hypoechoic nodules. In particular, acquired cystic disease has the potential for malignancy11,12 and it is therefore prudent to screen native kidneys, even after renal transplantation has been performed (Fig. 7.7).

Benign focal renal tumours

Angiomyolipoma

These are usually solitary, asymptomatic lesions, found incidentally on the scan. They tend to be well-defined and highly reflective, often rounded lesions containing blood vessels, muscle tissue and fat as the name suggests. They are usually asymptomatic, although the larger lesions can haemorrhage, causing haematuria and pain. AMLs are also associated with tuberose sclerosis, when they are often multiple and bilateral (Fig. 7.8). Because the contrast between the hypoechoic renal parenchyma and the hyperechoic AML is so great, very small lesions in the order of a few millimetres can be recognized on ultrasound.

Fig. 7.8 • (A) AML in the RK (calipers).

(B) Multiple, small AMLs in a patient with tuberose sclerosis.

An AML may cause a diagnostic dilemma, particularly in patients presenting with haematuria. They tend to be smaller and more echogenic than RCCs, and sometimes demonstrate shadowing, which is not normally seen in small carcinomas.13 When doubt persists, CT is usually able to differentiate in these cases by identifying the fat content of the lesion. However this is not infallible as a small number of AMLs (<5%) do not contain fat and a number of other tumours, such as lipoma, liposarcoma and some RCCs, also may contain fat.14

Adenoma

The renal adenoma is usually a small, well-defined hyperechoic lesion, similar in appearance to the AML. It is felt that adenomas are frequently early manifestations of renal carcinoma as distinct from a benign lesion14,15 and the two may be histologically indistinguishable.

Renal adenomas are often found in association with an RCC in the same or contralateral kidney,16 although these are radiologically indistinguishable from metastases. Because of the controversy surrounding the distinction between adenomas and small RCCs, the management of patients with these masses is uncertain. Most incidentally discovered, small (less than 3 cm) parenchymal renal masses are slow growing and may safely be monitored with CT or ultrasound, particularly in the elderly.17

There are a number of other benign renal tumours including leiomyoma, haemangioma, fibroma, oncocytoma and lymphangioma. Ultrasound is usually unable to characterize these, and CT may be helpful in evaluating the kidney further.14

Malignant renal tract masses

Imaging and management of malignant renal masses

Renal malignancy is not infrequently detected incidentally on ultrasound. Such lesions tend to be small (<4 cm) and isolated, with a good prognosis. Surveillance with ultrasound is an option in older patients or those with comorbidities, as many small lesions in older patients are stable in size. Any increase in size triggers more aggressive treatment.18

There is now a range of treatment options for renal malignancy; in addition to nephrectomy – still the treatment of choice in most centres – it is possible to offer minimally invasive techniques such as laparoscopic removal, nephron-preserving partial nephrectomy or percutaneous ablation (CT or ultrasound-guided.) CEUS may be used to guide percutaneous ablation for small renal tumours, and is useful in demonstrating tumour devascularization post ablation, or to monitor ablated tumours for signs of recurrence19 (see below and also Fig. 7.10).

Renal cell carcinoma

Ultrasound appearances

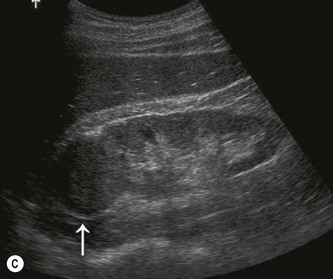

The RCC is a heterogeneous mass that often enlarges and deforms the shape of the kidney (Fig. 7.9). The mass may contain areas of cystic degeneration and/or calcification. It has a predilection to spread into the ipsilateral renal vein and IVC (see also Chapter 8). The increasing use of ultrasound, and its improved quality has led to an increase in the detection of small tumours, often in asymptomatic patients. Around 50% of all RCCs diagnosed fall into this category.20

(C) A small RCC (calipers) discovered incidentally during abdominal US.

(D) Colour Doppler of an exophytic RCC reveals disorganized, multidirectional blood flow.

Colour Doppler reveals a disorganized and increased blood flow pattern in larger masses with high velocities from the arteriovenous (AV) shunts within the carcinoma. CEUS may demonstrate a variety of contrast uptake patterns, with heterogeneous uptake, or hyper-enhancement in the sinusoidal phase.4–721 CEUS is also helpful in identifying residual tissue after tumours have been ablated (Fig. 7.10).

Fig. 7.10 • CEUS:

(A) Small RCC (calipers) pre-contrast.

(B) The lesion in (A) is hypervascular and takes up contrast throughout.

(C) Another small RCC post-ablation (arrow) before contrast.

Clearly smaller masses have a better prognosis and are likely to be early in stage with no metastases.20 With larger masses, liver, adrenal and lymph node metastases may be demonstrated on ultrasound. CT is used to stage the disease and will also demonstrate if metastases are present in the lungs.