3 Pathology of the gallbladder and biliary tree

Introduction

Ultrasound is an essential first-line investigation in suspected gallbladder and biliary duct disease. It is highly sensitive, accurate and comparatively cheap and is the imaging modality of choice.1 Gallbladder pathology is common and is asymptomatic in over 13% of the population.2

Cholelithiasis

The most commonly and reliably identified gallbladder pathology is gallstones. More than 10% of the population of the UK have gallstones. Many of these are asymptomatic (Box 3.1), which is an important point to remember. When scanning a patient with abdominal pain it should not automatically be assumed that, when gallstones are present, they are responsible for the pain. It is not uncommon to find further pathology in the presence of gallstones and a comprehensive upper abdominal survey should always be carried out. However, up to 35% of patients who have gallstones require surgery to relieve symptoms (Table 3.1).3

Table 3.1 Causes of a thickened gallbladder wall

| Physiological | Post-prandial |

| Inflammatory | Acute or chronic cholecystitis |

| Sclerosing cholangitis | |

| Crohn’s disease | |

| AIDS | |

| Adjacent inflammatory causes | Pancreatitis |

| Hepatitis | |

| Pericholecystic abscesses | |

| Non-inflammatory | Adenomyomatosis |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | |

| Focal areas of thickening due to metastases or polyps | |

| Leukaemia | |

| Oedema | Ascites from a variety of causes, including organ failure, lymphatic obstruction and portal hypertension |

| Varices | Varices of the gallbladder wall in portal hypertension |

Ultrasound appearances

There are three classic acoustic properties associated with stones in the gallbladder; they are highly reflective, mobile and cast a distal acoustic shadow. In the majority of cases, all these properties are demonstrated (Figs 3.1–3.3).

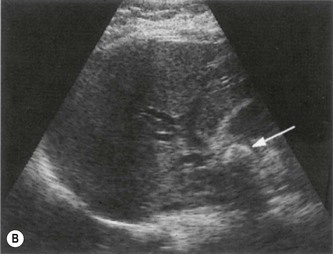

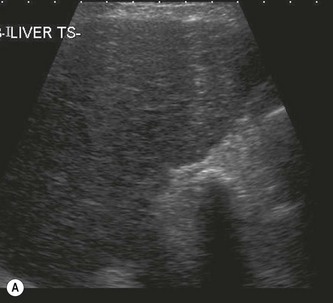

Fig. 3.1 • (A) LS and (B) TS through a gallbladder demonstrating stones with posterior acoustic shadowing.

(C) Tiny stones lie together to form a block of acoustic shadow behind the gallbladder.

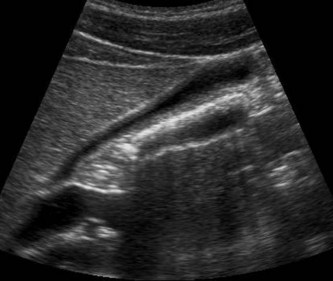

Fig. 3.2 • Gallstone mobility:

(A) Shadowing from a stone in the neck of the gallbladder.

(B) With the patient erect, the stone drops to the fundus of the gallbladder.

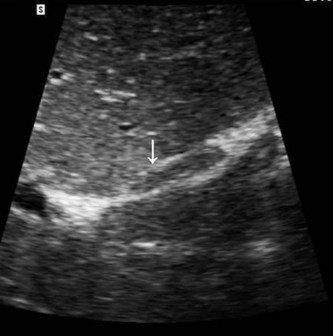

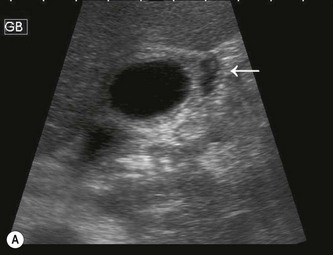

Fig. 3.3 • (A) Floating gallstones cast a shadow from the anterior gallbladder (arrow).

(B) Floating stones in the gallbladder lumen, mimicking gas-filled bowel.

Shadowing

The ability to display a shadow posterior to a stone depends on several factors:

Fig. 3.4 • (A) This small stone is wider than the beamwidth, and so casts an acoustic shadow (arrow).

Fig. 3.6 • The shadow from the stone in Figure 3.4 is obscured by overamplification of the echoes behind the gallbladder.

Reflectivity

Some stones are only poorly reflective, but should still cause a distal acoustic shadow.

Mobility

Most stones are gravity dependent, and this may be demonstrated by scanning the patient in an erect position (Fig. 3.2), when a mobile calculus will drop from the neck or body of the gallbladder to lie in the fundus. Some stones will float, however, forming a reflective layer just beneath the anterior gallbladder wall with shadowing that obscures the rest of the lumen (Fig. 3.3B). When the gallbladder lumen is contracted, either due to physiological or pathological reasons, any stones present are unable to move and this is also the case in a gallbladder packed with stones (Fig. 3.7D).

Occasionally a stone may become impacted in the neck, and movement of the patient is unable to dislodge it. Stones lodged in the gallbladder neck or cystic duct may result in a permanently contracted gallbladder, a gallbladder full of fine echoes due to inspissated (thickened) bile (Fig. 3.8) or a distended gallbladder due to a mucocoele (see below).

Choledocholithiasis

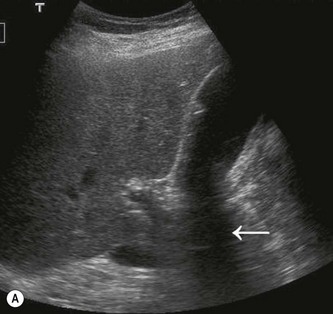

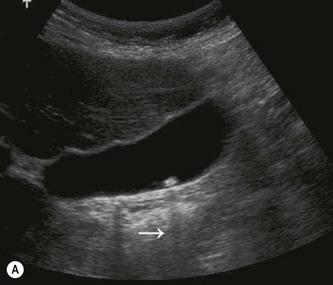

Choledocholithiasis develops in up to 20% of patients with gallstones.4 Stones may pass from the gallbladder into the common duct, or may develop de novo within the duct. Stones in the CBD may obstruct the drainage of bile from the liver causing obstructive jaundice. Due to shadowing from adjacent duodenum ductal stones are often difficult to demonstrate, and care must be taken to visualize the lower end of the duct if possible (Fig. 3.9).

It is also important to remember that stones in the CBD may be present without duct dilatation and attempts to image the entire common duct with ultrasound should always be made, even if it is of normal calibre at the porta (Fig. 3.10).

Other ultrasound signs to look for are shown in Box 3.2.

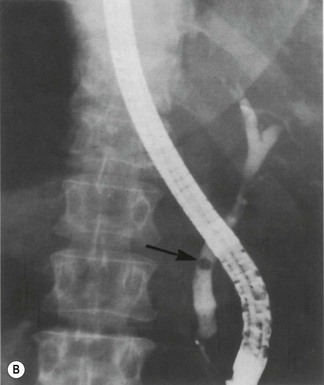

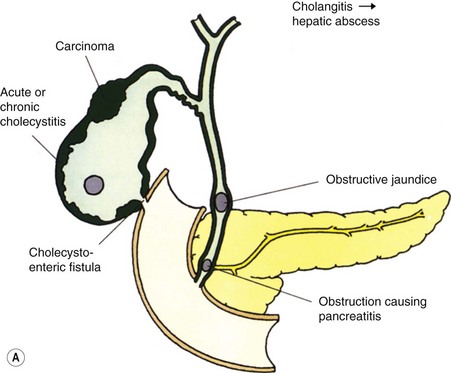

Possible complications of gallstones are outlined in Figure 3.11A. In rare cases, stones may perforate the inflamed gallbladder wall to form a fistula into the small intestine or colon. A large stone passing into the small intestine may impact in the ileum, causing intestinal obstruction (Fig. 3.11B).

Biliary reflux and gallstone pancreatitis

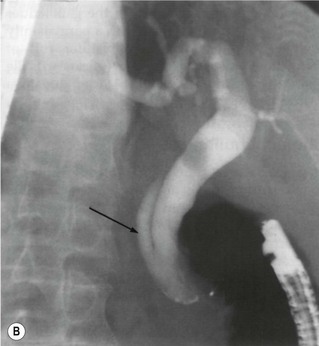

Bile reflux is also associated with anomalous cystic duct insertion (Fig. 3.12A, B) which is more readily recognized on MRCP than ultrasound.

Fig. 3.12 • (A) Anomalous insertion of the cystic duct (arrows) into the lower end of the CBD.

(B) Appearances of case in (A) are confirmed on ERCP. A stone is also present in the duct.

(C) MRCP showing stones in the CBD.

(D) ERCP can be used for therapeutic purposes, such as stone removal or stent insertion.

Further management of gallstones

MRCP and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrate stones in the duct with greater accuracy than ultrasound, particularly at the lower end of the CBD, which may be obscured by duodenal gas on ultrasound5 (Fig. 3.12C, D). ERCP is invasive, carrying a small risk of morbidity or, rarely, mortality due to perforation, infection or pancreatitis, but has the advantage of providing the therapeutic option of sphincterotomy and stone removal. This is the modality of choice when stones are known to exist in the duct, (for example following MRCP) and has supplanted surgical removal in many cases.6

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the preferred method of treatment for symptomatic gallbladder disease in an elective setting. Acute cholecystitis is also increasingly managed by early laparoscopic surgery, with a slightly higher rate of conversion to open surgery than elective cases.7 Laparoscopic ultrasound may be used as a suitable alternative to operative cholangiography to examine the common duct for residual stones during surgery.8 It compares well to cholangiography, with a sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 100%, and avoids any radiation dose, but has been slow to be adopted in the UK, as it requires specialized equipment and training.9 Both ultrasound and cholescintigraphy are used in monitoring post-operative biliary leaks or haematoma (Fig. 3.13).

Other, less common options include dissolution therapy and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL). However, these treatments are often only partially successful, require careful patient selection, and also run a significant risk of stone recurrence.10

Enlargement of the gallbladder

Owing to the enormous variation in size and shape of the normal gallbladder, it is not possible to diagnose pathological enlargement by simply using measurements. Three dimensional techniques may prove useful in assessing gallbladder volume11 but this is a technique which is only likely to be clinically useful in a minority of patients with impaired gallbladder emptying.

An enlarged gallbladder is frequently referred to as hydropic. It may be due to obstruction of the cystic duct (see below) or associated with numerous disease processes such as diabetes, primary sclerosing cholangitis, leptospirosis or in response to some types of drug. A pathologically dilated gallbladder, as opposed to one which is physiologically dilated, usually assumes a more rounded, tense appearance (Fig. 3.14).

Mucocoele of the gallbladder

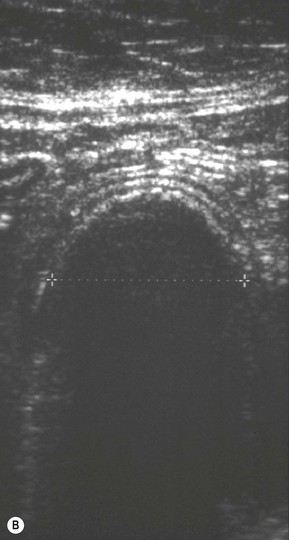

If the gallbladder is dilated in the absence of duct dilatation, make a careful search for an obstructing lesion at the neck; a stone in the cystic duct is more difficult to identify on ultrasound as it is not surrounded by echo-free bile (Fig. 3.8).

Mirizzi’s syndrome

On ultrasound the gallbladder is typically contracted and contains debris. A stone impacted at the neck may be demonstrated together with dilatation of the intrahepatic ducts with a normal-calibre lower common duct (Fig. 3.14). The diagnosis is a difficult one, as it is frequently not possible to rule out carcinoma. CT or MRI may assist in this distinction, and ERCP is still considered the ‘gold standard’ especially as it can offer therapeutic stone removal and/or stent placement.12 Endoscopic or intraductal ultrasound, if available, have improved the diagnostic accuracy of suspected cases.13 Although rare, it is an important diagnosis as cholecystectomy in these cases has a higher rate of operative and post-operative complications.14

The contracted or small gallbladder

Postprandial

The most likely cause of a contracted gallbladder is physiological, following a meal. (This may still occur despite instructions to fast and it is always worth enquiring when and what the patient has last eaten or drunk.) The normal gallbladder wall is thickened when contracted, and this must not be confused with a pathological process (Fig. 3.15).

Pathological causes of a small gallbladder

The reflective surface of the stones and distal shadowing are apparent, and the anterior gallbladder wall can be demonstrated with correct focusing and good technique (Figs 3.7D, 3.16). Do not confuse the appearances of a previous cholecystectomy, when bowel in the gallbladder fossa casts a shadow, for a contracted stone-filled gallbladder.

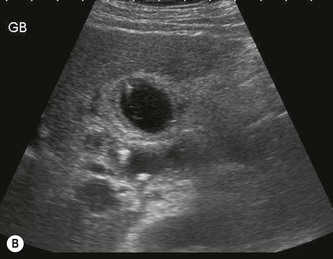

Fig. 3.16 • (A) Shadowing from the gallbladder fossa indicates a contracted gallbladder packed with stones.

(B) A small layer of bile is visible between the stones and the anterior gallbladder wall.

A less common cause of a small gallbladder is the microgallbladder associated with cystic fibrosis (Fig. 3.17). The gallbladder itself is abnormally small, rather than just contracted. Cystic fibrosis also carries an increased incidence of gallstones because of the altered composition of the bile and bile stasis and the wall might be thickened and fibrosed from cholecystitis.

Porcelain gallbladder

When the gallbladder wall becomes calcified the resulting appearance is of a solid reflective structure causing a distal shadow in the gallbladder fossa (Fig. 3.18). (This can be distinguished from a gallbladder full of stones where the wall can usually be seen anterior to the shadowing [Fig. 3.7D]).

There is an association between porcelain gallbladder and gallbladder carcinoma, so a prophylactic cholecystectomy is usually performed to pre-empt malignant development.15

Hyperplastic conditions of the gallbladder wall

Adenomyomatosis

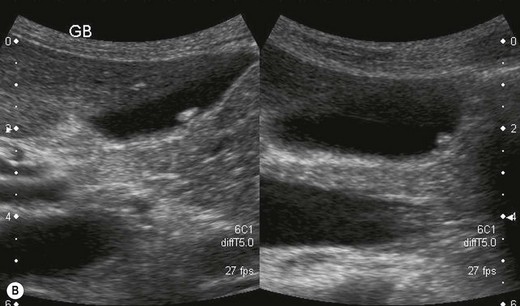

The epithelium that lines the gallbladder wall undergoes hyperplastic change – extending diverticulae into the adjacent muscular layer of the wall. These diverticulae, or sinuses (known as Rokitansky–Aschoff sinuses) are visible within the wall as fluid-filled spaces, (Fig. 3.19), which can bulge eccentrically into the lumen, and may contain echogenic material or even (normally pigment) stones.

The wall thickening may be focal or diffuse, and the sinuses may be little more than hypoechoic ‘spots’ in the thickened wall, or may become quite large cavities in some cases.16 Deposits of crystals in the gallbladder wall frequently result in distinctive ‘comet-tail’ artefacts, due to rapid small reverberations of the sound.17

Focal adenomyomatosis most often occurs at the fundus (Fig. 3.19C) and may be difficult to distinguish from carcinoma. [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) may be useful in the diagnosis of problem cases.18 Often asymptomatic, it may present with biliary colic although it is unclear whether this is caused by co-existent stones. Its distinctive appearance allows the diagnosis to be made easily, whether or not stones are present.

Cholecystectomy is performed in symptomatic patients – usually those who also have stones. Although essentially a benign condition, a few cases of associated malignant transformation have been reported, usually in patients with associated anomalous insertion of the pancreatic duct.19

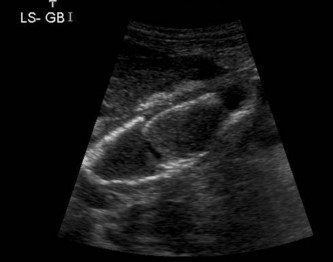

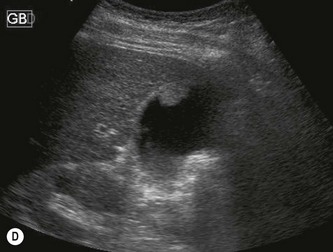

Polyps

Gallbladder polyps are common, usually asymptomatic lesions which are incidental findings in up to 5% of the population. Occasionally they are the cause of biliary colic. They are reflective structures, projecting into the gallbladder lumen, which do not cast an acoustic shadow. Unless on a long stalk they will remain fixed on varying the patient position and are therefore usually distinguishable from stones (Fig. 3.20).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree