Romaric Loffroy

Intractable hematuria from the bladder is a potentially life-threatening event that raises major therapeutic challenges. Causes of severe hematuria include mainly unresectable bladder carcinoma, radiation cystitis, and cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis. In many patients, bleeding cannot be adequately controlled by conservative measures, such as irrigation with formalin, silver nitrate or alum (aluminum sulfate) solution, intravesical hydrostatic pressure, hyperbaric oxygen, or endoscopic diathermy.1,2 Radical surgery is not always feasible because the operative risk is often high in this patient population. Angiography with embolization is a minimally invasive procedure that is emerging as a safe, and effective means to control bladder bleeding. Indeed, vesical artery embolization is occasionally indicated in these patients when all other measures have failed. Despite limited published experience with this procedure, success in 90% of patients is reported when the vesical arteries can be identified.3–8

DEVICE/MATERIAL DESCRIPTION

Conditioning of patients is important before embolization can be considered. Indeed, patients should be prepared appropriately before embolization, which should include patient resuscitation and optimum hydration, bladder irrigation with clot evacuation, and blood transfusion when indicated.

Pelvic endovascular procedures are usually performed using local anesthesia with a digital subtraction angiography unit. Unilateral or bilateral retrograde catheterization of the femoral artery is performed using a 5-Fr or 6-Fr sheath. Then, selective angiography of the internal iliac arteries is routinely performed using a 5-Fr Cobra or Simmons (Cordis Johnson&Johnson) type 2 catheter to delineate the pelvic arterial anatomy. The Simmons catheter tip is then placed as subselectively as possible into the anterior division of the internal iliac artery to opacify its branches. The vesical arteries can arise as discrete branches of the anterior division of the hypogastric artery and as branches from the pudendal and uterine arteries. Abnormal hypervascularity or even a mass may be seen at angiography, but visualization of extravasation is unusual. Based on angiographic findings, superselective catheterization of the vesical branches is routinely done using a 3-Fr coaxial microcatheter.

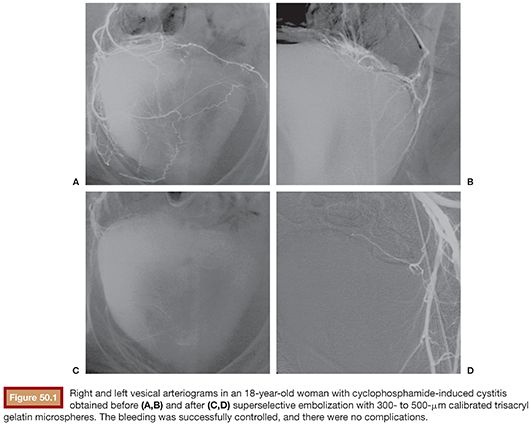

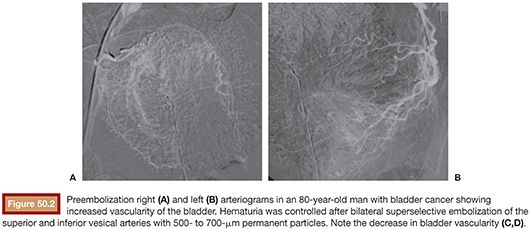

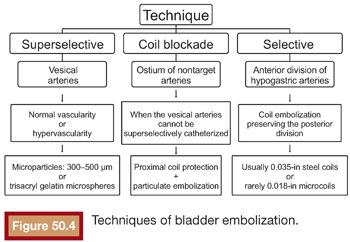

Flow-directed embolization is usually achieved using polyvinyl alcohol particles or trisacryl gelatin microspheres mixed with contrast medium (Fig. 50.1). Initially, 300- to 500-µm particles are typically used. As the distal branches fill, larger particles (usually 500- to 700-µm) are administered for a more proximal embolization (Fig. 50.2).

Occasionally when the vesical arteries cannot be selectively catheterized, coil blockade is performed. This technique consists of occluding a distal branch at its ostium while preserving flow in the vesical branches to steer the particles into these branches and protect the proximally embolized territory from distal particulate embolization. Coil blockade is performed using 0.018-in fibered or soft platinum microcoils of various lengths and diameters.8

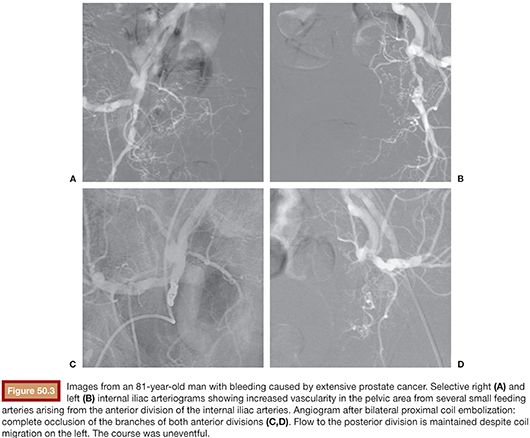

When the main distal branches of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery cannot be selectively catheterized, the catheter tip is left in the anterior division of the internal iliac artery and embolization is performed from this position using 0.035-in steel coils of an appropriate size or mechanically disrupted absorbable gelatin sponge powder sheet regardless of whether or not bleeding was detected by angiography (Fig. 50.3).5,6 Sometimes even when the bladder arteries were selectively catheterized and embolized, all anterior branches can be subsequently embolized. As needed, the same procedure is repeated on the opposite side via an ipsilateral or contralateral puncture. The main techniques of bladder embolization are described in Figure 50.4.

TECHNIQUE

Earlier studies suggest a higher risk of rebleeding after unilateral embolization than after bilateral embolization.9,10 Rebleeding after unilateral embolization is probably related to the rich collateral blood supply to the internal iliac artery from the contralateral internal iliac, inferior mesenteric, external iliac, and femoral arteries. To prevent rebleeding from these collateral vessels, the anterior division of the internal iliac artery should probably be embolized bilaterally regardless of whether the bleeding site is detectable on angiography.6,7,11–13

The influence of the type of embolic agent on clinical outcomes is controversial. In most previous series, the number of patients was too small to allow conclusions to be made about the best embolic agents for this indication.5–8,14 Although authors have used various embolic materials with time, particulate embolic agents, such as calibrated trisacryl gelatin microspheres, are preferred currently. Recanalization may develop after 2 to 3 weeks when gelatin sponge particles are used.15 When superselective catheterization is not possible, the distal arterial territory can be protected by placing coils immediately distal to the branches requiring embolization. This technique is helpful when a tumor has recruited several small collateral feeding vessels from the branches of the internal iliac artery. It can help prevent ischemic complications.

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

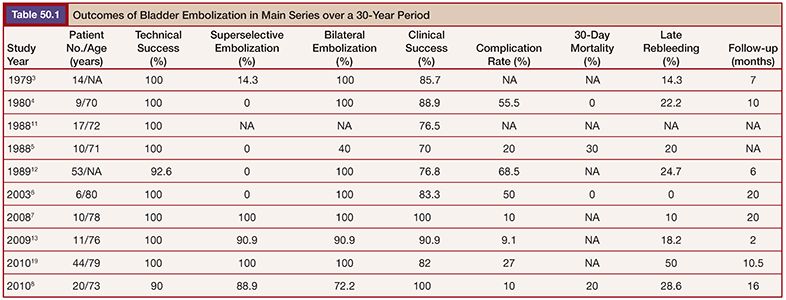

Severe hematuria that persists despite conventional treatment raises major therapeutic challenges. Patients are usually older and have radiation cystitis, cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis, or inoperable bladder or prostate cancer with bladder invasion and advanced disease. Prolonged or repeated hospitalization for bladder irrigation and multiple blood transfusions are not practical, and the risk of major morbidity associated with radical surgery is often unacceptably high. Endovascular embolization is a minimally invasive method that allows the patient to stay at home without catheters. Most studies of endovascular embolization for severe hematuria are small case series, but the technical success rate is high, ranging from 92.6% to 100%.3–8,13 Embolotherapy can provide at least short-term success that is adequate to palliatively improve quality of life with few complications. Indeed, the initial clinical success can be very high, especially in the most recently published studies in which superselective embolization was performed in most patients, supporting the use of this technique in such a setting (Table 50.1).7,8,13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree