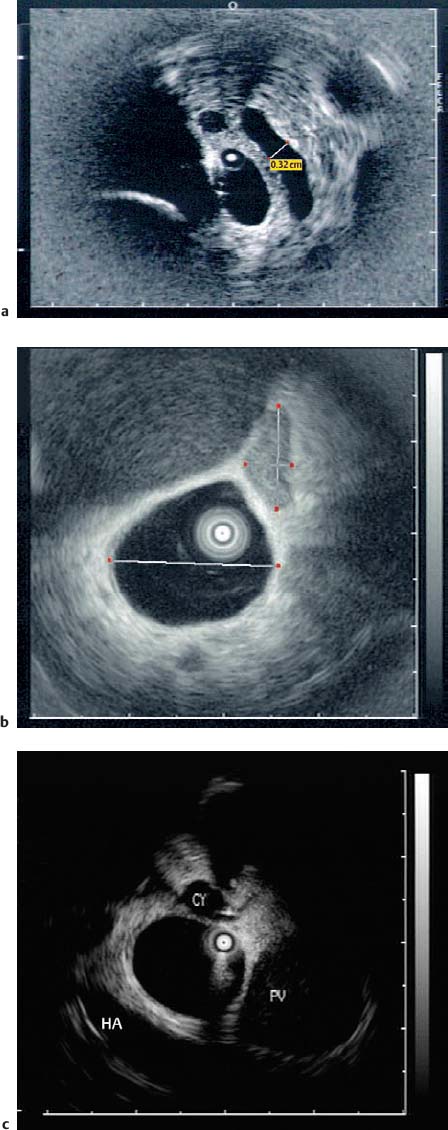

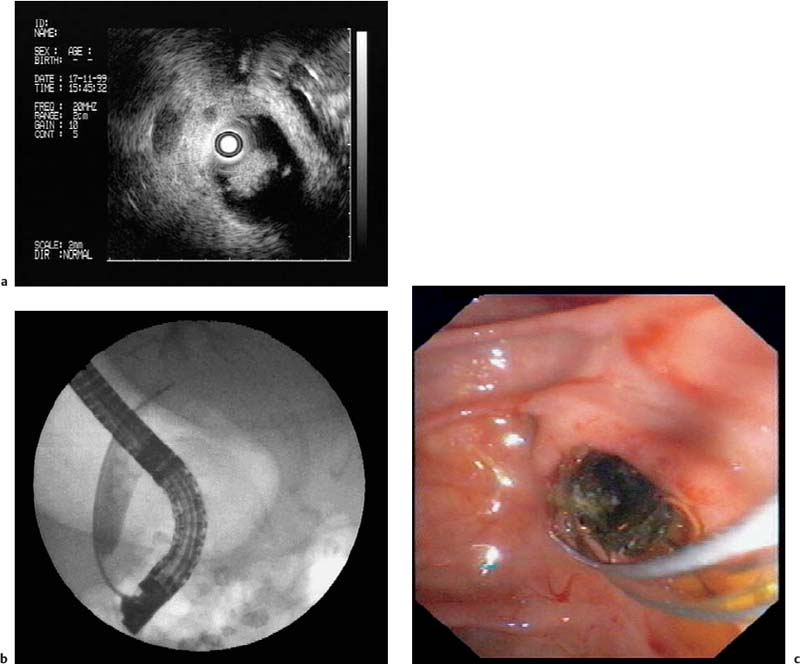

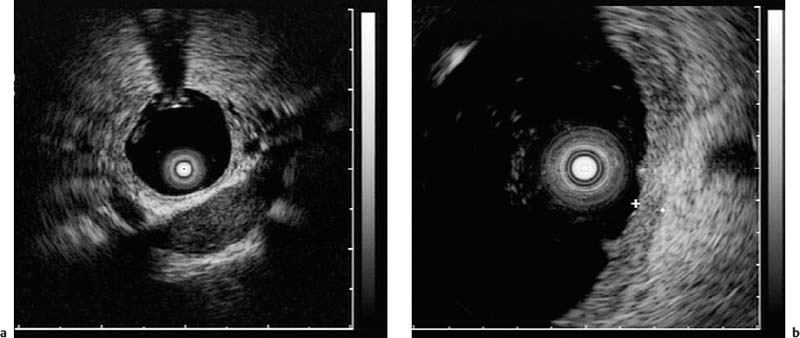

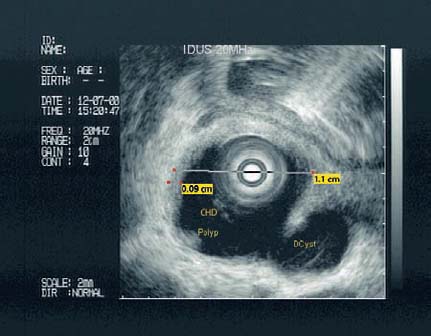

5 Intraductal Ultrasound Following initial reports on the intravascular use of high-frequency filiform miniprobes, biliary and pancreatic intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS) led to impressive imaging of these ducts and to valuable diagnostic information complementary to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), especially in patients with intraductal papillary tumors—further enhancing the potential of endoscopic ultrasonography.1–3 Although there are some features that are typical of malignant lesions, there are no criteria sufficiently reliable to allow differentiation between benign and malignant biliary or pancreatic lesions. Miniprobes with outer diameters of only 2–3 mm can be inserted through the instrument channel of standard endoscopes and provide high-frequency ultrasound images. The flexibility and small diameter of miniprobes allow intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS) in the biliary tract and pancreatic duct, as well as in the endobronchial system. High-frequency endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) probes are not well suited for screening examinations. The high resolution of miniprobes is useful for further differentiation and characterization of pathological structures that have been identified with other imaging methods (e.g., endoscopy or transabdominal ultrasound) or to answer specific clinical questions (e.g., suspected choledocholithiasis). Due to wear on the instruments, miniprobes have a short lifespan when used intraductally, and this is still a drawback with this endosonographic technique. No cost-benefit analyses have so far been published. In comparison with conventional endosonography, miniprobes work at substantially higher frequencies (12–30 MHz). This results in a high resolution (0.07–0.18 mm) that allows precise differentiation of the discrete wall layers in the esophagus, stomach, and bowel. Electronic miniprobes have a ring at the top that incorporates 64 transducer elements, which produce a 360° image. Electronic miniprobes are highly flexible, but have the disadvantage of restricted lateral resolution. In contrast, mechanical systems produce a 360° image with significantly better resolution, with a rotating transducer at the top of the probe. New miniprobe developments, with controlled automated retraction over a defined distance, allow three-dimensional reconstruction after complex image processing. Continuing research on probe design, which may improve the durability of the instruments and extend the depth of penetration, may encourage more widespread use of this novel technology. Intraductal Ultrasound of the Hepatobiliary System Small-caliber miniprobes can be inserted into the bile duct during ERCP. Prior papillotomy makes insertion easier, but may not be essential. Wire-guided miniprobes allow cannulation of the bile duct in nearly 100% of cases without previous sphincterotomy.4 Miniprobes can also be placed in specific intrahepatic bile ducts over a selectively placed guide wire. The position of the probe can be controlled radiographically during endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC). IDUS prolongs the examination time only marginally (≈ 5–10 minutes). It has been reported that it does not increase the complication rate with ERCP (one case of mild pancreatitis in 400 patients).5 Biliary IDUS provides a high-resolution display of structures in the hepatoduodenal ligament (portal vein, hepatic artery, and lymph nodes) (Fig. 5.1).6 Close to the papilla of Vater, IDUS depicts the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma with a penetration depth of 2 cm. In the intrahepatic position, the miniprobe shows parallel branches of the portal vein and the surrounding liver parenchyma. IDUS distinguishes three layers of the normal wall of the bile duct. The fine inner and more echogenic layer corresponds to the transition echo. The next layer, less echogenic, matches the mucosa and muscularis propria (fibromuscular layer). The outer more echogenic layer corresponds to the fatty tissue of the subserosa, the serosa, and the transition echo to neighboring organs.7 Fig. 5.1a–c Anatomy of the bile duct. a Intraductal (common bile duct) imaging of the pancreatic duct close to the papilla. b A lymph node in the hepatoduodenal ligament close to the cystic duct.6 c The origin of the cystic duct. PV, portalvein; HA, hepatic artery; CY, cystic duct. With both transabdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography, it can sometimes be difficult to detect gallstones in the bile duct. Interpreting magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the bile duct is still a sophisticated exercise. ERCP is therefore still the gold standard in the diagnosis and treatment of choledocholithiasis. However, even on ERCP, small stones may be overlooked, and it is difficult to distinguish between aerobilia and small stones. Conventional endosonography from a duodenal position has a high sensitivity of 95% for detecting choledocholithiasis, similar to that of ERCP.8 The best results reported for detecting choledocholithiasis were obtained with IDUS of the bile duct.9,10 In a prospective study by Palazzo, 97% of bile duct stones were detected with the miniprobe, 81% during ERCP, 61% with intravenous cholangiography, and 45% by transabdominal ultrasonography.11 Particular advantages of IDUS are that it makes it easier to distinguish between air, sludge, and stones and that it provides high resolution even of small stones (< 5 mm in diameter). IDUS of the bile duct can therefore be a valuable tool for diagnosing choledocholithiasis. If (wire-guided) IDUS of the bile duct is negative, sphincterotomy can be avoided. In contrast to invasive IDUS, we prefer extraductal ultrasound (EDUS; see also Chapter 20 on EUS of the hepatobiliary system) in most cases12 (see below). Review of the Literature IDUS is useful for detecting small residual bile duct stones during endoscopic balloon sphincteroplasty when stones are fragmented by mechanical lithotripsy, or when there is evidence of a dilated bile duct (> 10 mm).13 In 62 patients with suspected bile duct stones, the accuracy of ERC combined with IDUS for diagnosing bile duct stone and/or sludge was higher than that of ERC alone (97% versus 87%; P<0.05). With dilated bile ducts, the diagnostic accuracy of ERC combined with IDUS was also higher than that of ERC alone (95.5% versus 72.7%; P<0.05). Additional diagnostic information provided by IDUS included identification of cystic duct stones in five patients, characterization of bile duct strictures in two patients, and choledochal varices in one patient.14 In 65 patients in whom there was a strong suspicion of choledocholithiasis, the IDUS probe was inserted by means of the duodenoscope into the bile duct without a sphincterotomy. All stones identified by IDUS or retrograde cholangiography were removed after endoscopic sphincterotomy. The final diagnosis was choledocholithiasis in 59 patients. The bile duct diameter ranged from 0.6 to 2.3 cm, and the stone size from 2 mm to 2 cm. IDUS successfully identified all stones in these patients.15 IDUS is also helpful for confirming complete stone clearance after endoscopic stone removal, thereby decreasing the rate of early recurrence of common bile duct stones.16,17 Examples are shown in Figs. 5.2 and 5.3; by contrast, adenoma of the papilla with intraductal growth is illustrated in Fig. 5.4. Fig. 5.2a–c Choledocholithiasis. a Intraductal ultrasonography, showing choledocholithiasis and the accompanying acoustic shadow. b The corresponding endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram. c The corresponding endoscopic image. Fig. 5.3a, b a Choledocholithiasis with cholangitis. b Wall thickening is seen between the markers (scale: 2 mm). Fig. 5.4 Adenoma of the papilla with intraductal growth. Intraductal ultrasound is particularly helpful for detecting intraductal growth (polyps) and therefore indicates when surgery is required. CHD, common hepatic duct; DCyst, ductal cyst. IDUS can help to distinguish between benign and malignant bile strictures. The criteria for malignancy are fewer echogenic lesions extending beyond the borders of the organ, irregular ductal surfaces, interruption of the typical ultrasound wall layering, and a heterogeneous echo pattern.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Choledocholithiasis

Choledocholithiasis

Bile Duct Strictures

Bile Duct Strictures