and Michael F. Sorrell2

(1)

Herbert B. Saichek Professor of Radiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA

(2)

Robert L. Grissom Professor of Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA

161 Hepatoblastoma I: With Age-Dependent Differential Diagnosis

The liver is the third most common site for intra-abdominal malignancy in children, following adrenal neuroblastoma and Wilms’ tumor. Hepatic tumors account for only 1–4 % of the solid tumors in children. Of these malignant hepatic tumors, hepatoblastoma (HPB) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are the most common and account for the majority of the pediatric liver tumor.

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute data for the 21-year period from 1975 to 1995 shows that hepatoblastoma accounts for 79 % of liver cancer in children under the age of 15. However, since liver cancers account for only a little more than 1 % of childhood cancer, this results in about 100 cases of HPB a year in the USA. The incidence of hepatoblastoma is highest in infants and falls off rapidly, with most cases occurring prior to age 5.

The differential diagnosis for pediatric liver tumor depends on the age of the patient:

Infants (1–12 months): hemangioma, infantile hemangioendothelioma, and hamartoma

Children (1–10 years): hepatoblastoma (children <5 years: HPB 23× more common than HCC)

Adolescents (11–18 years): hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

HCC is less likely than hepatoblastoma to be resectable at diagnosis (10–30 %) and less responsive to chemotherapy. HCC has also been described after the Kasai procedure in patients with biliary atresia. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver (UESL) is less common than HPB and HCC. Benign infantile hemangioendothelioma usually undergoes spontaneous regression, but may be life threatening due to congestive heart failure and/or consumptive coagulopathy when treatment with resection, embolization, or arterial ligation is necessary. Mesenchymal hamartoma is a benign cystic lesion that should be resected whenever possible. Other more rare tumors include embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the biliary tree in children, and germ cell tumors occur in the neonatal liver. Metastatic liver lesions such as neuroblastoma, Wilms’ tumor, and lymphoma remain the most common neoplasm seen in the pediatric liver.

The clinical presentation of HPB and HCC is nonspecific and the symptoms may include abdominal swelling and discomfort owing to the size of the tumor. Fortunately, the rate of survival for pediatric patients with primary malignant liver tumor has significantly improved in the past decades, particularly due to advancements in neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which may render a previously inoperable tumor resectable. Currently, the only curative options for pediatric patients with primary tumor are complete surgical resection of the tumor and organ transplantation.

Hepatoblastoma, usually a multifocal tumor, appears with stippled or chunky calcifications in 40–50 % of patients loosely correlated to histologically detected osteoid matrix. The detection of calcifications is however not essential for diagnosis. At MR imaging, hepatoblastomas appear as multifocal large masses throughout the liver. As a result the liver presents with massive hepatomegaly. The tumors appear heterogeneous with frequent intratumoral hemorrhage, which is best visualized on the T1-weighted images. On the post-contrast images, the lesions show heterogeneous enhancement with restricted diffusion in the majority of the lesion. The liver may be surrounded by ascites. The appearance on the ultrasound and CT is similar to MRI; however, MR imaging has better soft tissue contrast and allows better delineation of the lesions and the background liver (Figs. 161.1 and 161.2).

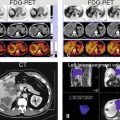

Fig. 161.1

Hepatoblastoma in a 17-month-old boy with MRI, CT, and ultrasound correlation. (a) Axial single-shot TSE image (SSTSE) shows a large heterogeneous mass (arrows) that has replaced much of the liver. Note the clear delineation between the mass and the surrounding liver (red arrows). (b) Axial T1-weighted GRE in-phase (T1 in phase) image shows a large focus of hemorrhage with the hepatoblastoma (arrow). (c) Axial arterial phase 3D T1-weighted GRE image (ART): the mass shows variable enhancement with solid areas enhancing more (arrow) than the necrotic areas (*). (d) Axial delayed phase GRE image (DEL): the lesion shows washout and remains heterogeneous. (e) Coronal T2-weighted SSTSE image (SSTSE): the lesion, with the surrounding perihepatic ascites, fills almost the entire abdomen. (f, g) Axial diffusion-weighted image (DWI) and ADC show restricted diffusion in large parts of the tumor (*). (h) Coronal delayed phase GRE image (DEL): the lesion shows large necrotic areas interspersed within the solid enhancing parts of the large mass

Fig. 161.2

Hepatoblastoma with MRI, CT, and ultrasound correlation. (a, d) Two ultrasound images show just parts of the entire lesion; the full extent of this large lesion is difficult to capture with ultrasound. (b, e) A graph (b) shows the age-dependent incidence of the pediatric liver cancers; note that most tumors are diagnosed before the age of 4 years. The highest incidence of about 9/100,000 occurs before the age of 1 year. The majority of these tumors are hepatoblastoma (HPB) as shown in the pie diagram in E. Please note that percentages in E are approximate and may show considerable variation. (c, f) Axial contrast-enhanced CT image shows the large liver mass with a hypertrophic hepatic artery (arrow in C) that is larger than the aorta and feeds the entire lesion. The tumor is poorly delineated from the liver due to inherently low soft tissue contrast of CT (HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, UESL undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree