Fig. 1

Area of high signal intensity seen on diffusion-weighted imaging suggestive of acute ischemic stroke

The brain does not, for the most part, have its own energy stores and relies on blood flow for its survival. Thus, it is susceptible to damage with even short periods of lack of blood flow. Normal cerebral blood flow (CBF) is around 50–60 ml/100 g/min. The brain may respond to changes in blood flow by local vasodilatation, opening collaterals and/or increasing the oxygen and glucose extraction from blood. Neuronal dysfunction occurs when the CBF decreases to around 20 ml/100 g/min. Permanent damage occurs when the CBF goes below 10 ml/100 g/min [3].

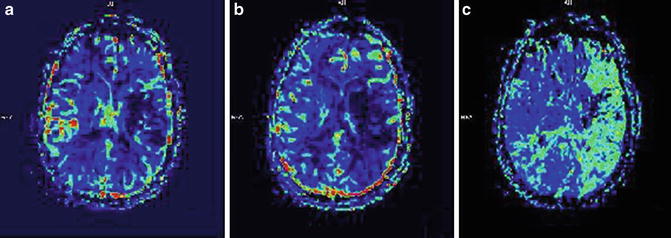

The majority of strokes are due to a small area of tissue that is deprived of blood flow. Often, a single blood vessel becomes blocked. The immediate region surrounding the blood vessel is most affected – this is called the ischemic core where cells are damaged and may die. Further away from the core, the cells may still be receiving a small amount of oxygen and glucose through diffusion from collateral vessels. The CBF in these regions is around 25–50 % of normal. The cellular integrity may be preserved in these regions. These cells can recover if blood flow is restored to them quickly. This region is called the penumbra [3]. Saving this tissue, the penumbra, is the goal of reperfusion therapy. Perfusion imaging can help visualize and separate tissue which is potentially salvageable from that which has already been infarcted (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

MRI perfusion imaging. (a) CBV (cerebral blood volume reduced in an area which likely corresponds with infarcted tissue), (b) CBF (cerebral blood flow which is reduced in an area larger than ischemic core), and (c) MTT (mean transit time which demonstrates slow arrival of contrast in the left hemisphere). The regions outside of the infarcted area with slow arrival of contrast represent potentially salvageable tissue amenable to reperfusion strategies

Initial Assessment of the Stroke Patient

The initial assessment of a stroke patient requires a broad approach as there are many other diagnoses which could mimic a stroke as well as stroke patients generally have multiple comorbidities. The basics should not be overlooked and the patient should be assessed for airway, breathing, and circulation. Attention should be paid to any other condition which could easily be reversible – such as hypoglycemia. A quick, concise history should be obtained including last known time normal as this will guide further therapy. A rapid assessment to determine if a patient is a candidate for thrombolytic therapy should be completed including National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and evaluation of inclusion and exclusion criteria for tPA (tissue plasminogen activator/brand name: Alteplase) as described later in this chapter. Point-of-care blood glucose should be obtained. The NIHSS, which quantifies the neurological exam, should be performed in the first 10 min from arrival prior to imaging if possible. Two IV lines (preferably 18 g) should be placed in case thrombolytic therapy or if contrast-enhanced imaging is necessary. Computerized tomography (CT) should be done within minutes of arrival and interpreted shortly thereafter. Labs including CBC (complete blood count), CMP (comprehensive metabolic panel), PT (prothrombin time), PTT (partial thromboplastin time), INR (international normalized ratio), and cardiac enzymes (if indicated) should be drawn. Lytic therapy may be initiated in the imaging suite to avoid delays. It may be started without waiting for laboratory test results unless the patient is on anticoagulation or has history of known bleeding diathesis. An electrocardiogram (EKG) should be completed as well. Next, investigations should be tailored to determine the cause of the stroke in each individual patient [4].

Summary

Obtain a quick, concise history including last known time normal, past medical history, risk factors for stroke, and medications, and perform evaluation of inclusion and exclusion criteria for tPA.

NIHSS should be performed.

IV lines placed.

Non-contrast head CT should be done and rapidly interpreted.

Labs should be drawn including CBC, CMP, PT, PTT, and INR and EKG completed.

Further investigations should be performed for evaluation of stroke etiology.

Acute Therapy: Ischemic Stroke

The phrase “time is brain” was intended to emphasize that brain tissue is rapidly lost during a stroke and rapid evaluation and treatment is necessitated. During each minute in which a large vessel ischemic stroke goes untreated, the patient can lose 1.9 million neurons, 13.8 billion synapses, and 12 km (7 miles) of axonal fibers [5].

Candidates for acute therapy should be identified as rapidly as possible. The goal of treatment during an ischemic stroke should be the restoration of blood flow as quickly and safely as possible. The approach to acute ischemic stroke treatment can be divided into vascular and neuronal strategies. Noninterventional vascular strategies focus on recanalization, increasing blood flow to the penumbra, and avoidance of clot propagation. Neuronal strategies focus on novel treatments such as neuroprotection.

Intravenous Thrombolysis

The first NINDS (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke) trial had shown that IV tPA had improved patient functional outcome at 3 months if the patient was treated within 3 h of symptom onset [6]. Later trials including ECASS 3 (European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study) showed that IV tPA not only was safe but patients benefitted from receiving the medication up to 4.5 h after stroke onset [7]. However, although the use of IV tPA within the 3–4.5 h window is generally accepted, it is currently not FDA (Food and Drug Administration) approved.

Multiple prior analyses of data of patients who received tPA have shown that each 15 min reduction in time to ignition of tPA treatment was associated with an increase in the odds of walking independently at discharge and being discharged to home rather than an institution. The same 15 min reduction in time to tPA treatment was associated with a decrease in the odds of death before discharge and symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation of infarction. Given these findings, one should strive to give tPA as rapidly as possible after identification of a potential candidate rather than later [8].

The initial NINDS stroke trial included patients with ischemic stroke who could be treated with IV tPA within 3 h of symptom onset. Six hundred twenty-four patients were randomized to treatment with placebo or IV tPA (0.9 mg/kg up to 90 mg, 10 % as a bolus followed by the rest over 60 min). At 3 months a complete or near recovery occurred in a statistically greater number of patients assigned to IV tPA than placebo (38 % vs. 21 %). Three-month mortality was not significantly different between the two groups. Severe systemic hemorrhage occurred in less than 1 % of patients [6].

ECASS 3 trial assigned 821 patients with acute ischemic stroke to receive IV tPA or placebo. Additional exclusion criteria were included in this study. Patients greater than 80 years old, NIHSS >25, those with a combination of previous stroke and diabetes, and those on anticoagulants regardless of INR were excluded from participation in the study. This was done to satisfy safety concerns from the European regulatory agency. Depending on local stroke center guidelines, the exclusion criteria from ECASS 3 may be taken into consideration when offering tPA to patients. The results of ECASS 3 showed that significantly more patients had a better outcome with IV tPA than placebo. There was no difference in mortality between IV tPA and placebo. Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was significantly more likely to occur with IV tPA administration than with placebo [7].

IV tPA should be offered to patients presenting within the 4.5 h (3–4.5 h use is recommended by American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) but not FDA approved and therefore off-label) window who meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Selection of candidates for intravenous thrombolysis requires a neurologic evaluation, neuroimaging, determination of eligibility in accordance with the inclusion, and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

Table 1

Guidelines for the use of IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)

Indications | Contraindications | Warningsa (relative contraindications) |

|---|---|---|

>18 years of age | Hemorrhage on imaging | Abnormal blood glucose (<50 mg/dL or >400 mg/dL) |

Measurable deficit NIHSS | Subarachnoid hemorrhage on imaging | Severe neurologic deficit (NIHSS > 22) |

Symptom onset within 3 h | Serious head or spinal trauma within the last 3 months | Major and early infarct signs on CT |

No hemorrhage on CT | History of intracranial hemorrhage | Minor neurologic deficit |

No contraindications (see next column) | Uncontrolled hypertension SBP > 185 or diastolic >110 mmHg | Rapidly improving symptoms |

Seizures at onset of stroke | ||

Active internal bleeding | ||

Intracranial neoplasm, AVM, or aneurysm | ||

Known bleeding diathesis (INR > 1.7, PT > 15, heparin within the past 48 h w/elevated aPTT | ||

Platelet count <100,000 |

Today’s guidelines for tPA administration come from the original trials designed to show the efficacy of tPA in acute stroke patients. Noncompliance with the guidelines has been associated with an increase in the risk of hemorrhage [9]. However, strict compliance with these criteria has excluded patients who may have benefitted from receiving tPA. Therefore, in extreme emergent situations, a rational individualized decision may be necessary for a certain patient.

Before starting IV tPA, the treating physician should make sure that treatment is within 4.5 h of onset of symptoms, there is a measurable neurologic deficit, inclusion and exclusion criteria are met, non-contrast head CT or MRI is done and does not show hemorrhage or large infarct, blood pressure parameters are met, IV lines are in place, and accurate body weight has been determined.

Serum glucose should be checked to ensure that hypoglycemia is not a cause of the precipitating neurologic findings. Patients with low platelet counts or elevated prothrombin times should be excluded. Uncontrollable hypertension is also exclusionary.

The tPA dose is calculated at 0.9 mg/kg of actual body weight with a maximum dose of 90 mg. Ten percent of the dose is given as a bolus over one minute. The rest is infused over an hour. Following administration of tPA, close monitoring of the patient is required with frequent assessment of vital signs and neurologic status as per local institution guidelines. A follow-up CT should be done 24 h post-tPA administration or sooner if there is any deterioration in clinical exam.

Tight blood pressure control is essential during the administration of thrombolytic therapy. The blood pressure must be less than or equal to 185/110 mmHg before starting the medication. Aggressive blood pressure lowering can be achieved using a variety of antihypertensives. Labetalol or IV nicardipine are routinely used. If blood pressure cannot be reliably controlled, thrombolytic therapy should not be administered. Following administration of tPA, the blood pressure needs to be kept below 180/105 for at least 24 h.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree