Chapter 31 Metastases to Abdominal-Pelvic Organs

Introduction

Metastasis is a complex process in which a tumor cell leaves the original site of disease, called the primary tumor, to spread to others parts of the body. Cancer cells can break away from a primary tumor, enter the blood vessels, circulate through the bloodstream, and be deposited in other organs of the body far from the primary tumor. When tumor cells metastasize to distant organs, the new tumor is called secondary or metastatic tumor.1

Epidemiology

Most tumors can metastasize. The most common sites of metastasis from solid tumors are the lungs, liver, and bones. However, the frequency, location, and patterns of metastases will depend on the primary tumor. Certain tumors rarely metastasize whereas some cancers tend to metastasize earlier than others.2 The presence of metastatic disease may also be correlated with the tumoral histology. Undifferentiated, anaplastic, and high-grade tumors have a tendency to give more metastases than well-differentiated and low-grade tumors.3 The cells in a metastatic tumor resemble those in the primary tumor. However, when the metastatic tumor is undifferentiated, the pathologist can use several adjuvant techniques, such as immunohistochemistry, to try to identify the origin of the primary tumor. In rare cases, patients will have metastatic disease without a primary tumor found, and these patients are considered to have a cancer of an unknown primary tumor.4

Patterns of Tumor Spread

The three principal pathways of tumor dissemination are hematogenic, lymphatic, and local invasion. The purpose of this chapter is to review hematogenous metastasis to intra-abdominal and pelvic organs. We divide our chapter by individual organ.

Key Points General principles

• Metastasis is a complex process in which tumor cells leave the original site to spread to other parts of the body.

• The most common sites of metastasis from solid tumors are the lungs, liver, and bones.

• The diagnosis of the presence of metastatic disease is one of the most important steps in staging patients.

• The three principal pathways of tumor dissemination are hematogeneous, lymphatic, and local invasion.

• Several imaging modalities may be used in the staging including US, CT, and MRI.

Key Points What the surgeon, radiation oncologist, and medical oncologist want to know

• The surgeon wants to know the presence of metastases, the number and size of the lesions, multifocality, and vascular involvement to plan resection.

• The radiation oncologist needs to know the location, size, and relationship of tumor to radiosensitive organs to plan radiation therapy field.

• The medical oncologist wants to know the number, location, and size of the lesions in the baseline study and the response to chemotherapy on follow-up imaging.

Liver

The most common solid organ to receive metastatic disease is the liver. Approximately 50% to 60% of patients who die of cancer have hepatic metastases at autopsy.5 The tumors that most commonly give metastases to the liver include lung; breast; gastrointestinal tract, such as esophageal, gastric, and colorectal; pancreas; and melanoma. Liver metastases usually appear as multiple solid lesions; however, in some cases, it may present as a solitary lesion, confluent masses, and infiltrative lesions that may mimic cirrhosis.6 Various imaging modalities may be used in the assessment of presence of hepatic metastases.

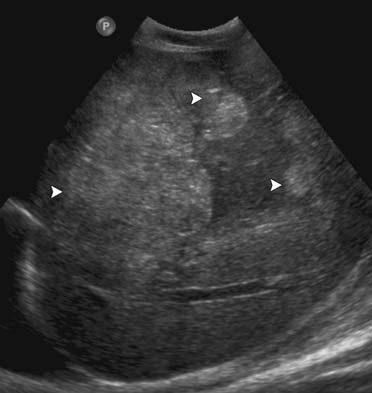

On US, liver metastases can have a variety of different appearances. Generally, the majority of the liver metastases present as multiple, solid, hypoechoic lesions from hypovascular tumors such as breast and lung cancer (Figure 31-1). They may show a peripheral hypoechoic rim known as the halo sign, which has been shown to represent a zone of proliferating tumor, a pseudocapsule, and/or compressed liver parenchyma.7 Other liver metastases may appear isoechoic, hyperechoic, and with an anechoic cystic component. Hyperechoic lesions are frequently associated with gastrointestinal primary tumors, renal cell carcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma (Figure 31-2). Cystic metastases may demonstrate mural solid nodules or thick septations. Calcified metastases present with posterior acoustic shadowing and are usually seen with mucinous adenocarcinoma of the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts.8

Although US has been widely used to detect liver metastases, its sensitivity in detecting liver metastases is lower than that of CT and MRI. Wernecke and coworkers9 reported a 53% sensitivity of US in the detection of hepatic masses. The application of new technologies such as microbubble intravenous contrast agents that improve the difference between the metastatic lesions and the background liver parenchyma increases the sensitivity of US in detecting hepatic metastases, even though its use is more common in some centers in Europe.10 Additional limitations of US include being operator-dependent, nonreproducible, and limited by abdominal gas.

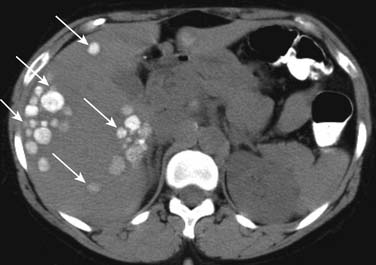

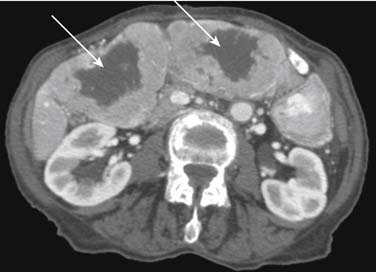

On unenhanced CT, the majority of the liver metastases appear as low-attenuating lesions compared with the surrounding liver parenchyma (Figure 31-3). Calcifications may be seen in the metastatic lesions from a primary mucin-secreting tumor of the gastrointestinal tract or ovary as well as after chemotherapy treatment (Figure 31-4). The use of intravenous contrast medium facilitates the distinction between focal lesions and the underlying liver parenchyma, improving the detection and characterization of hepatic lesions.11

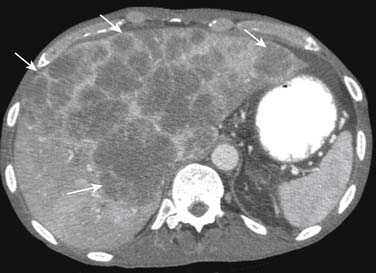

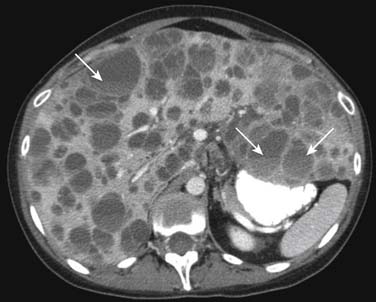

On enhanced CT, the imaging features of liver metastases will depend on the primary tumor. The most common liver metastases are hypovascular compared with the adjacent liver and appear as low-attenuation lesions on the portal venous phase of imaging, when the surrounding normal liver is at its peak of enhancement (Figures 31-5 and 31-6). It may also present a hypoattenuating halo and areas of hemorrhage and necrosis when the growth exceeds the tumor neovascularity (Figures 31-7 to 31-9). Hypovascular metastases usually originate from primary tumors from the gastrointestinal tract including colon, rectum, esophagus, and stomach and other sites such as lung, pancreas, and prostate.12

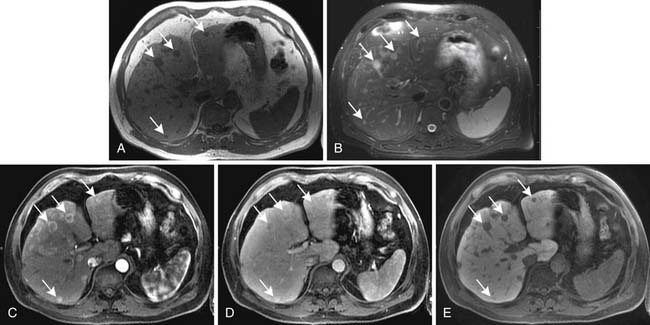

Alternatively, the hepatic metastases with increased arterial flow relative to normal liver are best seen as hypervascular lesions during the arterial dominant phase of enhancement. Moreover, they may show washout and become hypoattenuating on delayed images (Figure 31-10). Hypervascular metastases usually originate from renal cell carcinomas and neuroendocrine tumors. Other primary tumors that may present with hypervascular liver metastases include medullary thyroid cancer, melanoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors.13

The reported accuracy of CT in detecting hepatic metastases ranges from 75% to 96% based on studies with patients with colorectal cancer.14,15 The limitations of CT include radiation exposure and the risk of adverse reaction with the use of iodine intravenous contrast agents.

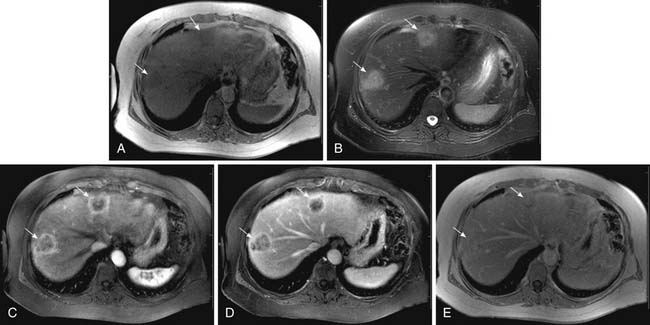

On MRI, hepatic metastases may have a variable appearance. The majority of liver metastases appear as low signal intensity on unenhanced T1-weighted images. Some tumors that may contain melanin or fat, such as metastases from melanoma and liposarcomas, respectively, can appear hyperintense on T1-weighted images. Hemorrhagic metastases may also appear hyperintense on T1-weighted images. On T2-weighted images, most liver metastases appear with high signal intensity (Figure 31-11). Lesions with central necrosis or cystic metastases can result in even higher signal intensity in T2-weighted images, whereas calcified lesions may be hypointense on T2-weighted images.16

After intravenous injection of gadolinium, most liver metastases show a peripheral ring of enhancement and are seen in the portal venous phase of imaging as hypointense lesions in comparison with the enhancing surrounding liver parenchyma (see Figure 31-11). Larger lesions may show cauliflower-like enhancement. The hypervascular metastases appear as foci of intense enhancement versus the background liver parenchyma during the arterial phase of enhancement (Figure 31-12). The presence of washout of the contrast from the lesion on delayed images is highly suspicious for malignancy.17 The reported sensitivity of MRI for the evaluation of suspected hepatic metastases ranges from 80% to 99%.18,19 The limitations of MRI include restriction to big centers and contraindication for patients with pacemakers and ferromagnetic implants.

Key Points Liver

• The liver is the most common solid organ to receive metastatic disease.

• Approximately 50% to 60% of patients who die of cancer have hepatic metastases at autopsy.

• Liver metastases may have a variable appearance and imaging features depend on the primary tumor.

• Most common liver metastases are hypovascular and appear as low-attenuation lesions compared with the adjacent liver parenchyma in the portal venous phase.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree