can be abstracted from concrete data structures using programming techniques such as generic programming [79]. However, generic algorithms still need to make certain assumptions about the data they operate on. The question remains what these concepts are that describe “data”: what properties should be expected by some algorithm from any kind of data provided for scientific visualization? Moreover, consistency among concepts shared by independent algorithms is also required to achieve interoperability among algorithms and eventually (independently developed) applications. While any particular problem can be addressed by some particular solution, a common concept allows to build a framework instead of just a collection of tools. Tools are what an end user needs to solve a particular problem with a known solution. However, when a problem is not yet clearly defined and a solution unknown, then a framework is required that allows exploration of various approaches and eventually adaption toward a specific direction that does not exist a priori.

Differential Geometry: Manifolds, Tangential Spaces, and Vector Spaces

. However, not all data occurring in scientific visualization are manifolds. The more general case of topological spaces will be discussed in sections “Topology: Discretized Manifolds” and “Topology.”

. However, not all data occurring in scientific visualization are manifolds. The more general case of topological spaces will be discussed in sections “Topology: Discretized Manifolds” and “Topology.” ) is a set V together with two binary operations vector addition +: V × V → V and scalar multiplication ∘: F × V → V. The mathematical concept of a vector is defined as an element v ∈ V. A vector space is closed under the operations + and ∘, i.e., for all elements u, v ∈ V and all elements λ ∈ F there is u + v ∈ V and λ ∘ u ∈ V (vector space axioms). The vector space axioms allow computing the differences of vectors and therefore defining the derivative of a vector-valued function

) is a set V together with two binary operations vector addition +: V × V → V and scalar multiplication ∘: F × V → V. The mathematical concept of a vector is defined as an element v ∈ V. A vector space is closed under the operations + and ∘, i.e., for all elements u, v ∈ V and all elements λ ∈ F there is u + v ∈ V and λ ∘ u ∈ V (vector space axioms). The vector space axioms allow computing the differences of vectors and therefore defining the derivative of a vector-valued function  as

as

Tangential Vectors

that computes the derivative along a curve

that computes the derivative along a curve  for an arbitrary scalar-valued function

for an arbitrary scalar-valued function  :

:

with μ = 0… n − 1, which define a basis of the tangential space T q(s)(M) on the n-dimensional manifold M at each point q(s) ∈ M:

with μ = 0… n − 1, which define a basis of the tangential space T q(s)(M) on the n-dimensional manifold M at each point q(s) ∈ M:

in the chart {x μ } and {∂ μ } are the basis vectors of the tangential space in this chart. In the following text the Einstein sum convention is used, which assumes implicit summation over indices occurring on the same side of an equation. Often tangential vectors are used synonymous with the term “vectors” in computer graphics when a direction vector from point A to point B is meant. A tangential vector on an n-dimensional manifold is represented by n numbers in a chart.

in the chart {x μ } and {∂ μ } are the basis vectors of the tangential space in this chart. In the following text the Einstein sum convention is used, which assumes implicit summation over indices occurring on the same side of an equation. Often tangential vectors are used synonymous with the term “vectors” in computer graphics when a direction vector from point A to point B is meant. A tangential vector on an n-dimensional manifold is represented by n numbers in a chart.Covectors

that map tangential vectors v ∈ T(M) to a scalar value v(f) for any function

that map tangential vectors v ∈ T(M) to a scalar value v(f) for any function  defines another vector space which is dual to the tangential vectors. Its elements are called covectors:

defines another vector space which is dual to the tangential vectors. Its elements are called covectors:

. A covector V can thus be visually imagined as a sequence of coplanar (locally flat) planes at distances given by the magnitude of the covector that count the number of planes which are crossed by a vector

. A covector V can thus be visually imagined as a sequence of coplanar (locally flat) planes at distances given by the magnitude of the covector that count the number of planes which are crossed by a vector  . This number is V (w). For instance, for the Cartesian coordinate function x, the covector dx “measures” the “crossing rate” of a vector w in the direction along the coordinate line x; see Figs. 1 and 2. On an n-dimensional manifold a covector is correspondingly symbolized by a (n − 1)-dimensional subspace.

. This number is V (w). For instance, for the Cartesian coordinate function x, the covector dx “measures” the “crossing rate” of a vector w in the direction along the coordinate line x; see Figs. 1 and 2. On an n-dimensional manifold a covector is correspondingly symbolized by a (n − 1)-dimensional subspace.

}. (a) Radial field dr ∂ r . (b) Azimuthal field dϕ ∂ ϕ view of the equatorial plane (z-axis towards eye). (c) Altitudal field dθ ∂ θ slice along the z-axis

}. (a) Radial field dr ∂ r . (b) Azimuthal field dϕ ∂ ϕ view of the equatorial plane (z-axis towards eye). (c) Altitudal field dθ ∂ θ slice along the z-axisTensors

of tensors, which reduces the dimensionality of the tensor:

of tensors, which reduces the dimensionality of the tensor:

, as they can be used to define a metric or inner product on the tangential vectors. Its inverse, defined by operating on the covectors, is called the co-metric. A metric, same as the co-metric, is represented as a symmetric n × n matrix in a chart for an n-dimensional manifold.

, as they can be used to define a metric or inner product on the tangential vectors. Its inverse, defined by operating on the covectors, is called the co-metric. A metric, same as the co-metric, is represented as a symmetric n × n matrix in a chart for an n-dimensional manifold.

Exterior Product

is an algebraic construction generating vector space elements of higher dimensions from elements of a vector space V. The new vector space is denoted Λ(V ). It is alternating, fulfilling the property

is an algebraic construction generating vector space elements of higher dimensions from elements of a vector space V. The new vector space is denoted Λ(V ). It is alternating, fulfilling the property  (which results in

(which results in  ). The exterior product defines an algebra on its elements, the exterior algebra (or Grassmann algebra). It is a sub-algebra of the tensor algebra consisting of the antisymmetric tensors. The exterior algebra is defined intrinsically by the vector space and does not require a metric. For a given n – dimensional vector space V, there can at most be nth power of an exterior product, consisting of n different basis vectors. The (n + 1)th power must vanish, because at least one basis vector would occur twice, and there is exactly one basis vector in Λ n (V ).

). The exterior product defines an algebra on its elements, the exterior algebra (or Grassmann algebra). It is a sub-algebra of the tensor algebra consisting of the antisymmetric tensors. The exterior algebra is defined intrinsically by the vector space and does not require a metric. For a given n – dimensional vector space V, there can at most be nth power of an exterior product, consisting of n different basis vectors. The (n + 1)th power must vanish, because at least one basis vector would occur twice, and there is exactly one basis vector in Λ n (V ).

Visualizing Exterior Products

and

and  (three components in 3D, six components in 4D). A bi-tangential vector (13) can be understood visually as an (oriented, i.e., signed) plane that is spun by the two defining tangential vectors, independently of the dimensionality of the underlying base space. A bi-covector (14) corresponds to the subspace of an n-dimensional hyperspace where a plane is “cut out.” In three dimensions these visualizations overlap: both a bi-tangential vector and a covector correspond to a plane, and both a tangential vector and a bi-covector correspond to one-dimensional direction (“arrow”). In four dimensions, these visuals are more distinct but still overlap: a covector corresponds to a three-dimensional volume, but a bi-tangential vector is represented by a plane same as a bi-covector, since cutting out a 2D plane from four-dimensional space yields a 2D plane again. Only in higher dimensions these symbolic representations become unique. However, both a co-vector and a pseudo-vector will always correspond to (i.e., appear as) an (n − 1)-dimensional hyperspace.

(three components in 3D, six components in 4D). A bi-tangential vector (13) can be understood visually as an (oriented, i.e., signed) plane that is spun by the two defining tangential vectors, independently of the dimensionality of the underlying base space. A bi-covector (14) corresponds to the subspace of an n-dimensional hyperspace where a plane is “cut out.” In three dimensions these visualizations overlap: both a bi-tangential vector and a covector correspond to a plane, and both a tangential vector and a bi-covector correspond to one-dimensional direction (“arrow”). In four dimensions, these visuals are more distinct but still overlap: a covector corresponds to a three-dimensional volume, but a bi-tangential vector is represented by a plane same as a bi-covector, since cutting out a 2D plane from four-dimensional space yields a 2D plane again. Only in higher dimensions these symbolic representations become unique. However, both a co-vector and a pseudo-vector will always correspond to (i.e., appear as) an (n − 1)-dimensional hyperspace.

and

and  . However, when inversing a coordinate x μ → −x μ , they flip sign, whereas a “true” scalar does not. An example known from Euclidean vector algebra is the allegedly scalar value constructed from the dot and cross product of three vectors

. However, when inversing a coordinate x μ → −x μ , they flip sign, whereas a “true” scalar does not. An example known from Euclidean vector algebra is the allegedly scalar value constructed from the dot and cross product of three vectors  which is the negative of when its arguments are flipped:

which is the negative of when its arguments are flipped:

. In computer graphics, both left-handed and right-handed coordinate systems occur, which may lead to lots of confusions.

. In computer graphics, both left-handed and right-handed coordinate systems occur, which may lead to lots of confusions.

(V 0 the electrostatic, A k the magnetic vector potential), take the form

(V 0 the electrostatic, A k the magnetic vector potential), take the form

Geometric Algebra

that is associative (uv)w = u(vw), left distributive

that is associative (uv)w = u(vw), left distributive  , and right distributive (

, and right distributive ( and reduces to the inner product as defined by the metric v 2 = g(v, v). It can be shown that the sum of the outer product and the inner product fulfill these requirements; this defines the geometric product as the sum of both:

and reduces to the inner product as defined by the metric v 2 = g(v, v). It can be shown that the sum of the outer product and the inner product fulfill these requirements; this defines the geometric product as the sum of both:

and

and  are of different dimensionalities ({n} {{2} and {n} {{0}, respectively), the result must be in a higher-dimensional vector space of dimensionality {n} {{2} + {n} {{0}. This space is formed by the linear combination of k-vectors; its elements are called multivectors. Its dimensionality is

are of different dimensionalities ({n} {{2} and {n} {{0}, respectively), the result must be in a higher-dimensional vector space of dimensionality {n} {{2} + {n} {{0}. This space is formed by the linear combination of k-vectors; its elements are called multivectors. Its dimensionality is  .

.

Vector and Fiber Bundles

will be used to denote a fiber bundle over the base space B. It is also said that the space F fibers over the base space B.

will be used to denote a fiber bundle over the base space B. It is also said that the space F fibers over the base space B. . Every differentiable manifold possesses a tangent bundle

. Every differentiable manifold possesses a tangent bundle  . The dimension of

. The dimension of  is twice the dimension of the underlying manifold M, its elements are points plus tangential vectors. T p (M) is the fiber of the tangent bundle over the point p.

is twice the dimension of the underlying manifold M, its elements are points plus tangential vectors. T p (M) is the fiber of the tangent bundle over the point p.Topology: Discretized Manifolds

. The dimension of the cell is k. Zero-cells are called vertices, one-cells are edges, two-cells are faces or polygons, and three-cells are polyhedra – see also section “Chains.” An n-cell within an n-dimensional space is just called a “cell.” (n − 1)-cells are sometimes called “facets” and (n − 2)-cells are known as “ridges.” For k-cells of arbitrary dimension, incidence and adjacency relationships are defined as follows: two cells c 1, c 2 are incident if c 1 ⊆ ∂ c 2, where ∂ c 2 denotes the border of the cell c 2. Two cells of the same dimension can never be incident because dim(c 1) ≠ dim(c 2) for two incident cells c 1, c 2. c 1 is a side of c 2 if dim(c 1) < dim(c 2), which may be written as c 1 < c 2. The special case

. The dimension of the cell is k. Zero-cells are called vertices, one-cells are edges, two-cells are faces or polygons, and three-cells are polyhedra – see also section “Chains.” An n-cell within an n-dimensional space is just called a “cell.” (n − 1)-cells are sometimes called “facets” and (n − 2)-cells are known as “ridges.” For k-cells of arbitrary dimension, incidence and adjacency relationships are defined as follows: two cells c 1, c 2 are incident if c 1 ⊆ ∂ c 2, where ∂ c 2 denotes the border of the cell c 2. Two cells of the same dimension can never be incident because dim(c 1) ≠ dim(c 2) for two incident cells c 1, c 2. c 1 is a side of c 2 if dim(c 1) < dim(c 2), which may be written as c 1 < c 2. The special case  may be denoted by c 1 ≺ c 2. Two k -cells c 1, c 2 with k > 0 are called adjacent if they have a common side, i.e.,

may be denoted by c 1 ≺ c 2. Two k -cells c 1, c 2 with k > 0 are called adjacent if they have a common side, i.e.,

within an n-dimensional Hausdorff space is an ordered sequence of k-cells

within an n-dimensional Hausdorff space is an ordered sequence of k-cells  of decreasing dimensions such that

of decreasing dimensions such that  . These relationships allow to determine topological neighborhoods: adjacent cells are called neighbors. The set of all k + 1 cells which are incident to a k-cell forms a neighborhood of the k-cell. The cells of a Hausdorff space X constitute a topological base, leading to the following definition: a (“closure-finite, weak-topology”) CW-complex

. These relationships allow to determine topological neighborhoods: adjacent cells are called neighbors. The set of all k + 1 cells which are incident to a k-cell forms a neighborhood of the k-cell. The cells of a Hausdorff space X constitute a topological base, leading to the following definition: a (“closure-finite, weak-topology”) CW-complex  , also called a decomposition of a Hausdorff space X, is a hierarchical system of spaces

, also called a decomposition of a Hausdorff space X, is a hierarchical system of spaces  , constructed by pairwise disjoint open cells c ⊂ X with the Hausdorff topology

, constructed by pairwise disjoint open cells c ⊂ X with the Hausdorff topology  , such that X (n) is obtained from X (n−1) by attaching adjacent n-cells to each (n − 1)-cell and

, such that X (n) is obtained from X (n−1) by attaching adjacent n-cells to each (n − 1)-cell and  . The respective subspaces X (n) are called the n-skeletons of X. A CW complex can be understood as a set of cells which are glued together at their subcells. It generalizes the concept of a graph by adding cells of dimension greater than 1.

. The respective subspaces X (n) are called the n-skeletons of X. A CW complex can be understood as a set of cells which are glued together at their subcells. It generalizes the concept of a graph by adding cells of dimension greater than 1. . Note that a cell does not need to be “straight,” such that, e.g., a two-cell may be constructed from a single vertex and an edge connecting the vertex to itself, as, e.g., illustrated by J. Hart [34]. Alternative approaches toward the definition of cells are more restrictively based on isometry to Euclidean space, defining the notion of “convexity” first. However, it is recommendable to avoid the assumption of Euclidean space and treating the topological properties of a mesh purely based on its combinatorial relationships.

. Note that a cell does not need to be “straight,” such that, e.g., a two-cell may be constructed from a single vertex and an edge connecting the vertex to itself, as, e.g., illustrated by J. Hart [34]. Alternative approaches toward the definition of cells are more restrictively based on isometry to Euclidean space, defining the notion of “convexity” first. However, it is recommendable to avoid the assumption of Euclidean space and treating the topological properties of a mesh purely based on its combinatorial relationships.Ontological Scheme and Seven-Level Hierarchy

Hierarchy object | Identifier type | Identifier semantic |

|---|---|---|

Bundle | Floating point number | Time value |

Slice | String | Grid name |

Grid | Integer set | Topological properties |

Skeleton | Reference | Relationship map |

Representation | String | Field name |

Field | Multidimensional index | Array index |

Field Properties

Topological Skeletons

Non-topological Representations

3 Differential Forms and Topology

Differential Forms

. They are commonly called co-variant vectors, covectors (see section “Tangential Vectors”), or Pfaff-forms. The set of one-forms generates the dual vector space or cotangential space T p ∗(M). It is important to highlight that the tangent vectors v ∈ T P (M) are not contained in the manifold itself, so the differential forms also generate an additional space over P ∈ M. In the following, these one-forms are generalized to (alternating) differential forms.

. They are commonly called co-variant vectors, covectors (see section “Tangential Vectors”), or Pfaff-forms. The set of one-forms generates the dual vector space or cotangential space T p ∗(M). It is important to highlight that the tangent vectors v ∈ T P (M) are not contained in the manifold itself, so the differential forms also generate an additional space over P ∈ M. In the following, these one-forms are generalized to (alternating) differential forms. as a linear mapping which assigns a scalar to each one-form α by

as a linear mapping which assigns a scalar to each one-form α by

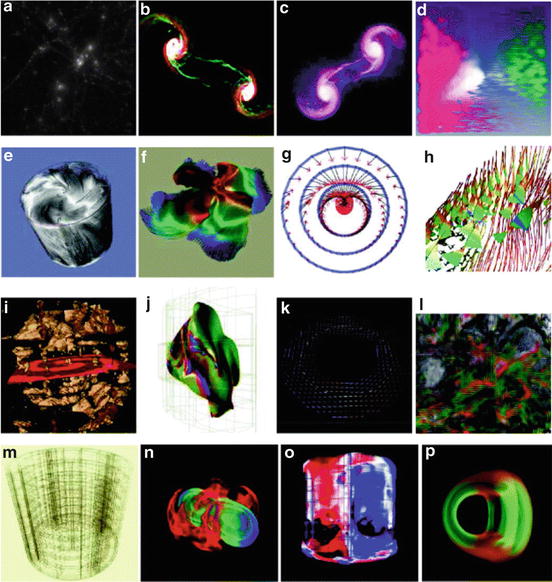

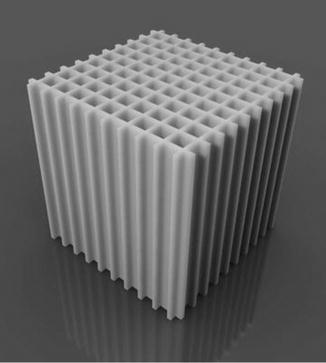

with C p representing an integration domain, e.g., an interval x 1 and x 2, results in the same value f(x 2) − f(x 1). In the general case, a p-form is not always the exterior derivative of a p-one-form; therefore, the integration of p-forms is not independent of the integration domain. An example is given by the exterior derivative of a p-form β resulting in a p + 1-form γ = d β. The structure of such a generated differential form can be depicted by a tube-like structure such as in Fig. 7. While the wedge product of an r-form and an s-form results in an r + s-form, this resulting form is not necessarily representable as a derivative. Figure 7 depicts a two-form which is not constructed by the exterior derivative but instead by

with C p representing an integration domain, e.g., an interval x 1 and x 2, results in the same value f(x 2) − f(x 1). In the general case, a p-form is not always the exterior derivative of a p-one-form; therefore, the integration of p-forms is not independent of the integration domain. An example is given by the exterior derivative of a p-form β resulting in a p + 1-form γ = d β. The structure of such a generated differential form can be depicted by a tube-like structure such as in Fig. 7. While the wedge product of an r-form and an s-form results in an r + s-form, this resulting form is not necessarily representable as a derivative. Figure 7 depicts a two-form which is not constructed by the exterior derivative but instead by  , where α and β are one-forms. In the general case, a p-form attached on an n-dimensional manifold M is represented by using (n − p)-dimensional surfaces.

, where α and β are one-forms. In the general case, a p-form attached on an n-dimensional manifold M is represented by using (n − p)-dimensional surfaces.

, where α and β are one-forms. The topologically tube-like structure of the two-forms is enclosed by the depicted planes

, where α and β are one-forms. The topologically tube-like structure of the two-forms is enclosed by the depicted planesChains

and a vector space

and a vector space  can be written by

can be written by

, the following classification for elements of a cell complex is obtained:

, the following classification for elements of a cell complex is obtained:

0: if the cell is not in the complex

1: if the unchanged cell is in the complex

− 1: if the orientation is changed

, whereby τ p i ∈ K. The boundary operator ∂ p defines a (p − 1)-chain computed from a p-chain:

, whereby τ p i ∈ K. The boundary operator ∂ p defines a (p − 1)-chain computed from a p-chain:  . The boundary of a cell τ p j can be written as alternating sum over elements of dimension p − 1:

. The boundary of a cell τ p j can be written as alternating sum over elements of dimension p − 1:![$$\displaystyle{ \partial _{p}\tau _{p}^{i} =\sum \nolimits _{ i}(-1)^{i}[k_{ 0},k_{1},\ldots,\tilde{k}_{i},\ldots k_{n}] }$$](/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/A183156_2_En_35_Chapter_Equ29.gif)

indicates that k i is deleted from the sequence. This map is compatible with the additive and the external multiplicative structure of chains and builds a linear transformation:

indicates that k i is deleted from the sequence. This map is compatible with the additive and the external multiplicative structure of chains and builds a linear transformation: