Miscellaneous Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders

Familial Idiopathic Hyperphosphatasia

Familial idiopathic hyperphosphatasia, also known as hyperostosis corticalis deformans juvenilis, familial osteoectasia, or juvenile Paget disease, is a rare autosomal recessive disorder affecting young children, generally within their first 18 months and exhibiting a striking predilection for those of Puerto Rican descent. The condition is associated with progressive bone deformities. Clinically, it is characterized by dwarfism, painful bowing of the limbs, muscular weakness, abnormal gait, acetabular protrusio, pathologic fractures, spinal deformities, loss of vision and hearing, elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase, and an increase in the amount of leucine aminopeptidase. Recent investigations suggest that this disorder is caused by mutations in the TNFRSF11B gene located on the long arm of chromosome 8 (8q24) that result in deficiency of osteoprotegerin (OPG). OPG is a cytokine receptor, also known as osteoclastogenesis inhibitor factor (OCIF), which normally suppresses bone resorption by regulating activity of osteoclasts.

Imaging Evaluation

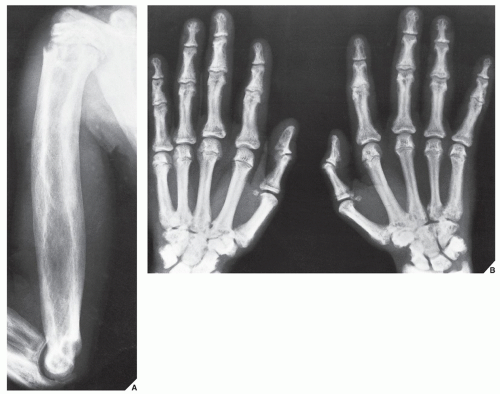

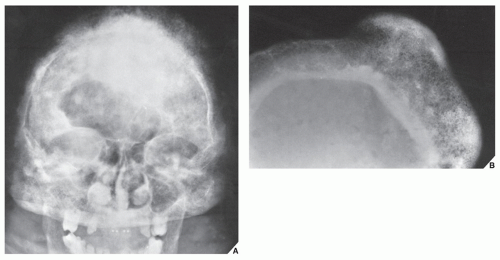

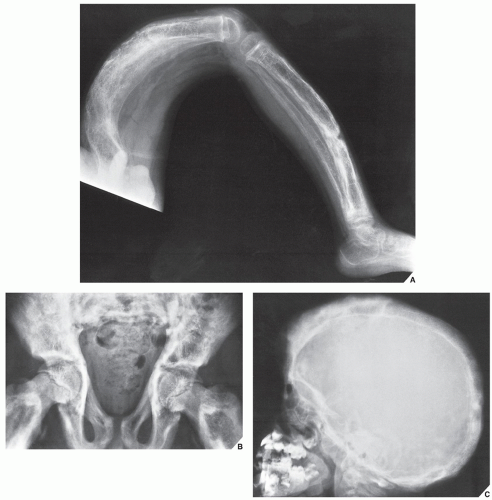

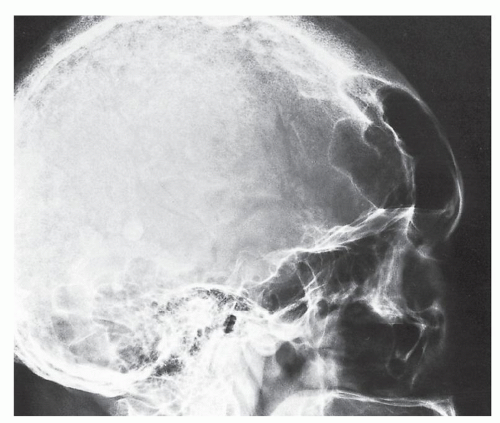

Increased turnover of bone and skeletal collagen demonstrated by radionuclide bone scan is a characteristic finding in familial idiopathic hyperphosphatasia. Its radiographic features are typical. Although this disorder has no relationship to classic Paget disease, it is often referred to as juvenile Paget disease, and it exhibits similar radiographic features. The long bones are increased in size, showing thickening of the cortex and a coarse trabecular pattern (Figs. 30.1 and 30.2). Likewise, bowing deformities are common, as are involvement of the pelvis and skull (Fig. 30.3). However, unlike Paget disease, the epiphyses are usually not affected.

Treatment consists of administration of bisphosphonates and calcitonins.

Differential Diagnosis

A few conditions exist similar to familial idiopathic hyperphosphatasia that belong to the general group of endosteal hyperostoses, or hyperostosis corticalis generalisata. In particular, an autosomal recessive form of these disorders, van Buchem disease, although classified as chronic hyperphosphatasia tarda, is in fact a distinct dysplasia. Its onset is later than that of congenital hyperphosphatasia, and the age of patients ranges from 25 to 50 years. The major radiographic finding is a symmetric thickening of the cortices of the long and short tubular bones. The femora are not bowed, and the articular ends are spared. The cranial bones show marked thickening of the vault and the base. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels are elevated, but calcium and phosphorus levels are normal.

Acromegaly

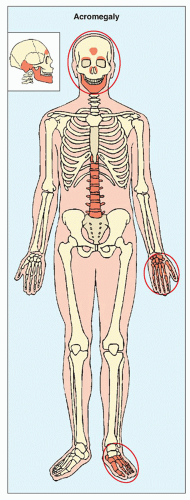

Increased secretion of growth hormone (somatotropin) by the eosinophilic cells of the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland, as a result of either hyperplasia of the gland or a tumor, leads to acceleration of bone growth. If this condition develops before skeletal maturity (i.e., while the growth plates are still open), then it results in gigantism; development after skeletal maturity results in acromegaly. The onset of symptoms is usually insidious, and the involvement of certain target sites in the skeleton is typical (Fig. 30.4). Gradual enlargement of the hands and feet as well as exaggeration of facial features are the earliest manifestations. The characteristic facial changes result from overgrowth of the frontal sinuses, protrusion of the jaw (prognathism), accentuation of the orbital ridges, enlargement of the nose and lips, and thickening and coarsening of the soft tissues of the face.

Radiographic Evaluation

Radiographic examination reveals a number of characteristic features of this condition. A lateral radiograph of the skull demonstrates thickening of the cranial bones and increased density. The diploë may be obliterated. The sella turcica, which houses the pituitary gland, may or may not be enlarged. The paranasal sinuses become enlarged (Fig. 30.5) and the mastoid cells become overpneumatized. The prognathous jaw, one of the obvious clinical features of this condition, is apparent on the lateral view of the facial bones.

The hands also exhibit revealing radiographic changes. The heads of the metacarpals are enlarged, and irregular bony thickening along the margins, simulating beak-like osteophytes, may be seen. Increase in the size of the sesamoid at the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb may be helpful in evaluating acromegaly. Values of the sesamoid index (determined by the height and width of this ossicle measured in millimeters) greater than 30 in women and greater than 40 in men suggest acromegaly; however, generally, the dividing line between normal and abnormal values is not sharp enough to allow individual borderline cases to be diagnosed on the basis of this index alone. Characteristic changes are also seen in the distal

phalanges; their bases enlarge and the terminal tufts form spur-like projections. The joint spaces widen as a result of hypertrophy of articular cartilage (Fig. 30.6), and hypertrophy of the soft tissues may also occur, leading to the development of square, spade-shaped fingers.

phalanges; their bases enlarge and the terminal tufts form spur-like projections. The joint spaces widen as a result of hypertrophy of articular cartilage (Fig. 30.6), and hypertrophy of the soft tissues may also occur, leading to the development of square, spade-shaped fingers.

Evaluation of the foot on the lateral view allows an important measurement to be made, the heel-pad thickness. This index is determined by the distance from the posteroinferior surface of the calcaneus to the nearest skin surface. In a normal 150-lb subject, the heel-pad thickness should not exceed 22 mm. For each additional 25 lb of body weight, 1 mm can be added to the basic value; thus, 24 mm would be the highest normal value for a 200-lb person. If the heel-pad thickness is greater than the established normal value, then acromegaly is a strong possibility (Fig. 30.7), and determination of growth hormone level by immunoassay is called for.

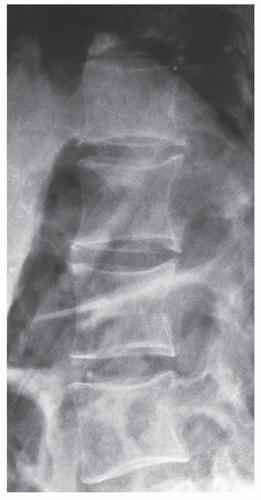

The spine in acromegaly may also reveal identifying features. A lateral radiograph of the spine may disclose an increase in the anteroposterior diameter of a vertebral body as well as scalloping or increased concavity of the posterior vertebral margin (Fig. 30.8). Although the exact mechanism of this phenomenon is not known, bone resorption has been implicated as a potential cause. Other conditions have also been associated with posterior vertebral scalloping (Table 30.1). In addition, thoracic kyphosis is often increased in spinal acromegaly and lumbar lordosis is accentuated. The invertebral disk space may be wider than normal because of overgrowth of the cartilaginous portion of the disk.

The articular abnormalities seen in acromegaly are the result of a common complication, degenerative joint disease, which is in turn the result of overgrowth of the articular cartilage and subsequent inadequate nourishment of abnormally thick cartilage. The combination of joint space narrowing, osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and formation of cyst-like lesions is similar to the primary osteoarthritic process.

FIGURE 30.8 Acromegalic spine. Lateral radiograph of the thoracolumbar spine of a 49-year-old woman demonstrates posterior vertebral scalloping, a phenomenon apparently caused by bone resorption. |

TABLE 30.1 Causes of Scalloping in Vertebral Bodies | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Gaucher Disease

Classification

Gaucher disease is a familial inherited disturbance transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait, arising from numerous mutations at the genetic locus encoding the enzyme glucocerebrosidase (glucocerebrosidase cerebroside β-glucosidase) located on chromosome 1 (1q21), that leads to the defective activity of lysosomal hydrolase. It is a metabolic disorder characterized by the abnormal deposition of cerebrosides (glycolipids) in the reticuloendothelial cells of the spleen, liver, and bone marrow. These altered macrophages, called Gaucher cells, are the histologic hallmark of the disease. Gaucher disease is classified into three distinct categories (phenotypes):

Type I: The nonneuronopathic, or adult type, is the most common form, occurring mainly in Ashkenazi Jews. Onset is in the patient’s first or second decade, and the individuals affected usually live normal life spans. Bone abnormalities and hepatosplenomegaly characterize this form of the disease, although some patients may not show any symptoms.

Type II: The acute neuronopathic form is lethal within the patient’s first year. This type apparently has no predilection for any ethnic group. Hepatosplenomegaly is invariably present, in addition to brain damage and seizure disorder.

Type III: The subacute juvenile neuronopathic form, occurring mainly in Swedish nationality from the Norbotten region begins in the latter part of the first year and follows a malignant course similar to that of type II. Patients present with hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, respiratory problems, mental retardation, and seizures and usually die by the end of their second decade of life.

The presenting clinical features of patients depend on the type of disease they have. The adult form of the disorder (type I) is the most common one and typically presents with abdominal distention secondary to splenomegaly. Recurrent bone pain is a sign of skeletal involvement, and acute severe bone pain together with swelling and fever suggests acute pyogenic osteomyelitis. This clinical complex, which is the result of ischemic necrosis of bone, has been called aseptic osteomyelitis. Pingueculae may be present in the eyes, and the skin may acquire a brown pigmentation. Epistaxis or other hemorrhages caused by thrombocytopenia may occur. The diagnosis is made by demonstrating characteristic Gaucher cells in bone marrow aspirate or in a biopsy specimen from the liver.

Imaging Evaluation

The radiographic examination in Gaucher disease reveals characteristic findings. There is a diffuse osteoporosis that is frequently associated with medullary expansion. In the ends of the long bones, this phenomenon is referred to as the Erlenmeyer flask deformity (Fig. 30.9 and Table 30.2). Localized bone destruction assuming a honeycomb appearance is also typically seen (Fig. 30.10); gross osteolytic destruction is usually limited to the shafts of the long bones and occasionally may be seen within the cortical bone. Moreover, sclerotic changes are common, occurring secondary to a repair process or bone infarctions (Fig. 30.11). Medullary bone infarction and a periosteal reaction may lead to a bone-within-bone phenomenon, which may resemble osteomyelitis (Fig. 30.12). Hermann and associates conducted a study of 29 patients with type I Gaucher disease using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to determine the usefulness of this technique in the evaluation of bone marrow involvement. The results of this investigation suggest that MRI is a valuable noninvasive modality in this respect to assess disease activity. Apparently, the patients with decreased signal intensity within bone marrow on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted images, but showing a relative increase in signal intensity from T1 weighting to T2 weighting can be considered to have an “active process” that correlates well with their symptoms. More recently, quantitative MRI technique in form of quantitative chemical shift imaging (QCSI) was introduced. This technique quantifies the fat content in bone marrow by using the difference in resonant frequencies between fat and water, thus detecting the reduction in the fat fraction that occurs when Gaucher cells displace the normal triglyceride-rich adipocytes in bone marrow. Low bone marrow fat fractions as detected by QCSI have been shown to correspond to increased clinical activity of the disease and emerging osseous complications. This technique also can be effective as a tool for monitoring response to treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree