chapter 3 Modes of Radioactive Decay

Radioactive decay is a process in which an unstable nucleus transforms into a more stable one by emitting particles, photons, or both, releasing energy in the process. Atomic electrons may become involved in some types of radioactive decay, but it is basically a nuclear process caused by nuclear instability. In this chapter we discuss the general characteristics of various modes of radioactive decay and their general importance in nuclear medicine.

a General Concepts

Radioactive decay results in the conversion of mass into energy. If all the products of a particular decay event were gathered together and weighed, they would be found to weigh less than the original radioactive atom. Usually, the energy arises from the conversion of nuclear mass, but in some decay modes, electron mass is converted into energy as well. The total mass-energy conversion amount is called the transition energy, sometimes designated Q.* Most of this energy is imparted as kinetic energy to emitted particles or converted to photons, with a small (usually insignificant) portion given as kinetic energy to the recoiling nucleus. Thus radioactive decay results not only in the transformation of one nuclear species into another but also in the transformation of mass into energy.

b Chemistry and Radioactivity

Radioactive decay is a process involving primarily the nucleus, whereas chemical reactions involve primarily the outermost orbital electrons of the atom. Thus the fact that an atom has a radioactive nucleus does not affect its chemical behavior and, conversely, the chemical state of an atom does not affect its radioactive characteristics. For example, an atom of the radionuclide 131I exhibits the same chemical behavior as an atom of 127I, the naturally occurring stable nuclide, and 131I has the same radioactive characteristics whether it exists as iodide ion ( I− ) or incorporated into a large protein molecule as a radioactive label. Independence of radioactive and chemical properties is of great significance in tracer studies with radioactivity—a radioactive tracer behaves in chemical and physiologic processes exactly the same as its stable, naturally occurring counterpart, and, further, the radioactive properties of the tracer do not change as it enters into chemical or physiologic processes.

A second exception is that the average lifetimes of radionuclides that decay by processes involving orbital electrons (e.g., internal conversion, Section E, and electron capture, Section F) can be changed very slightly by altering the chemical (orbital electron) state of the atom. The differences are so small that they cannot be detected except in elaborate nuclear physics experiments and again are of no practical consequence in nuclear medicine.

c Decay by β− Emission

The electron (e−) and the neutrino (ν) are ejected from the nucleus and carry away the energy released in the process as kinetic energy. The electron is called a β− particle. The neutrino is a “particle” having no mass or electrical charge.* It undergoes virtually no interactions with matter and therefore is essentially undetectable. Its only practical consequence is that it carries away some of the energy released in the decay process.

Decay by β− emission may be represented in standard nuclear notation as

The parent radionuclide (X) and daughter product (Y) represent different chemical elements because atomic number increases by one. Thus β− decay results in a transmutation of elements. Mass number A does not change because the total number of nucleons in the nucleus does not change. This is therefore an isobaric decay mode, that is, the parent and daughter are isobars (see Chapter 2, Section D.3).

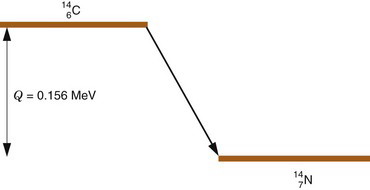

Radioactive decay processes often are represented by a decay scheme diagram. Figure 3-1 shows such a diagram for 14C, a radionuclide that decays solely by β− emission. The line representing 14C (the parent) is drawn above and to the left of the line representing 14N (the daughter). Decay is “to the right” because atomic number increases by one (reading Z values from left to right). The vertical distance between the lines is proportional to the total amount of energy released, that is, the transition energy for the decay process (Q = 0.156 MeV for 14C).

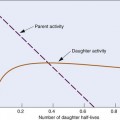

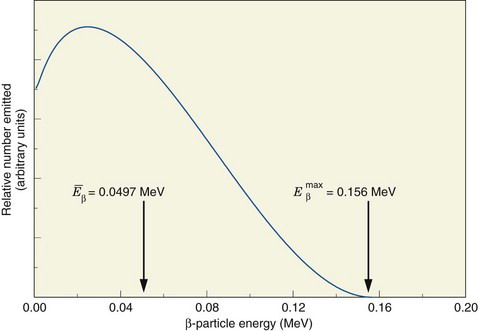

The energy released in β− decay is shared between the β− particle and the neutrino. This sharing of energy is more or less random from one decay to the next. Figure 3-2 shows the distribution, or spectrum, of β−-particle energies resulting from the decay of 14C. The maximum possible β−-particle energy (i.e., the transition energy for the decay process) is denoted by  (0.156 MeV for 14C). From the graph it is apparent that the β− particle usually receives something less than half of the available energy. Only rarely does the β− particle carry away all the energy (

(0.156 MeV for 14C). From the graph it is apparent that the β− particle usually receives something less than half of the available energy. Only rarely does the β− particle carry away all the energy ( ).

).

FIGURE 3-2 Energy spectrum (number emitted vs. energy) for β particles emitted by 14C. Maximum β−-particle energy is Q, the transition energy (see Fig. 3-1). Average energy  is 0.0497 MeV, approximately

is 0.0497 MeV, approximately  .

.

(Data courtesy Dr. Jongwha Chang, Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute.)

Beta particles present special detection and measurement problems for nuclear medicine applications. These arise from the fact that they can penetrate only relatively small thicknesses of solid materials (see Chapter 6, Section B.2). For example, the thickness is at most only a few millimeters in soft tissues. Therefore it is difficult to detect β− particles originating from inside the body with a detector that is located outside the body. For this reason, radionuclides emitting only β− particles rarely are used when measurement in vivo is required. Special types of detector systems also are needed to detect β− particles because they will not penetrate even relatively thin layers of metal or other outside protective materials that are required on some types of detectors. The implications of this are discussed in Chapter 7.

The properties of various radionuclides of medical interest are presented in Appendix C. Radionuclides decaying solely by β− emission listed there include 3H, 14C, and 32P.

d Decay by (β−, γ ) Emission

In some cases, decay by β− emission results in a daughter nucleus that is in an excited or metastable state rather than in the ground state. If an excited state is formed, the daughter nucleus promptly decays to a more stable nuclear arrangement by the emission of a γ ray (see Chapter 2, Section D.5). This sequential decay process is called (β−, γ) decay. In standard nuclear notation, it may be represented as

Note that γ emission does not result in a transmutation of elements.

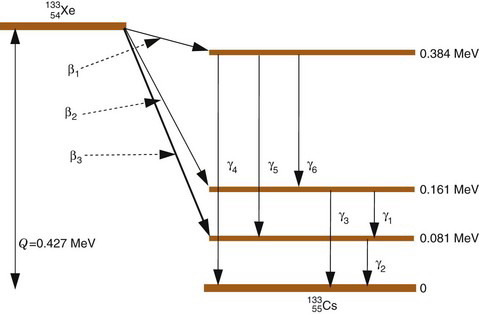

An example of (β−, γ) decay is the radionuclide 133 Xe, which decays by β− emission to one of three different excited states of 133Cs. Figure 3-3 is a decay scheme for this radionuclide. The daughter nucleus decays to the ground state or to another, less energetic excited state by emitting a γ ray. If it is to another excited state, additional γ rays may be emitted before the ground state is finally reached. Thus in (β−, γ) decay more than one γ ray may be emitted before the daughter nucleus reaches the ground state (e.g., β2 followed by γ1 and γ 2 in 133 Xe decay).

The number of nuclei decaying through the different excited states is determined by probability values that are characteristic of the particular radionuclide. For example, in 133 Xe decay (Fig. 3-3), 99.3% of the decay events are by β3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

. This varies from one radionuclide to the next but has a characteristic value for any given radionuclide. Typically,

. This varies from one radionuclide to the next but has a characteristic value for any given radionuclide. Typically,  . For 14C,

. For 14C,  .

.