MR imaging allows detailed evaluation of temporomandibular (TMJ) anatomy because of its inherent tissue contrast and high resolution. Joint biomechanics can be assessed through imaging patients in the closed and open jaw positions. Despite the accuracy of MR imaging in detecting disc position, results must be interpreted together with clinical findings, because an anteriorly displaced disc can be seen in up to one-third of asymptomatic patients, and a normal disc position can be seen in up to one-quarter of symptomatic patients. Interpretation of MR imaging requires knowledge of the normal anatomy and an understanding of normal and abnormal biomechanics.

- •

Internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is very common.

- •

MR imaging is the preferred study for evaluating the TMJ.

- •

Key TMJ features to evaluate include disc position, disc morphology, condylar translation, presence of a joint effusion, and superimposed osteoarthritis.

- •

Disc position can be classified as normal, anteriorly displaced with recapture, and anteriorly displaced without recapture.

- •

MR imaging is also useful to exclude other diagnoses that may mimic internal derangement, including infection and inflammatory arthritis.

Introduction

Up to 20% to 30% of the population experiences pain related to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), and 3% to 7% seek treatment. TMJ disorder or dysfunction (TMD) is an umbrella term that encompasses several clinical entities that affect the TMJ, muscles of mastication, or both. Internal derangement of the disc and joint mechanics is the most common of these various clinical diagnoses. Internal derangement of the TMJ is defined as an abnormal positional and functional relationship between the disc and articulating surfaces. Common clinical symptoms include pain and joint sounds (clicking or crepitus), but joint sounds are nonspecific as they are found in up to 35.8% of asymptomatic persons under 18 years of age. However, the clinical evaluation can be unreliable as many symptoms of internal derangement overlap with myofascial pain dysfunction, which is often a stress-related psychophysiologic disorder. Therefore, MR imaging has become part of the standard evaluation of TMD. Less common entities affecting the TMJ include infection, trauma, neoplasm, and inflammatory arthritis.

MR imaging allows detailed evaluation of TMJ anatomy because of its inherent tissue contrast and high resolution using surface coils. MR also allows assessment of joint biomechanics through imaging patients in the closed and open jaw positions. Furthermore, a dynamic study can be obtained with cine MR imaging as the patient opens and closes the jaw. Despite the sensitivity and specificity of MR imaging in detecting disc position, results must be interpreted together with clinical findings, because an anteriorly displaced disc can be seen in up to 34% of asymptomatic patients, and a normal disc position can be seen in up to 23% of symptomatic patients. Interpretation of MR imaging of the TMJ requires knowledge of the normal anatomy and an understanding of normal and abnormal biomechanics.

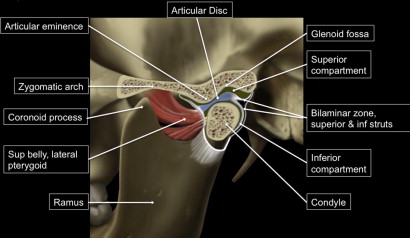

Normal anatomy

The TMJ is an unusual synovial joint in that the articular surfaces are covered with fibrocartilage rather than hyaline cartilage. The articular capsule is attached to the edges of the glenoid fossa, including the articular tubercle, and to the neck of the mandible. The fibrocartilaginous articular disc, or meniscus, lies within the articular capsule between the mandibular condyle and glenoid fossa, dividing the synovial cavity into superior and inferior synovial compartments ( Fig. 1 ). The lateral pterygoid muscle inserts anteriorly on the mandibular condyle at the pterygoid fovea and the anterior band of the disc. The articular disc, or meniscus, is a biconcave avascular connective tissue structure composed of three segments: anterior band, intermediate zone, and posterior band.

The anterior and posterior bands are triangular in shape and connected by the thin intermediate zone. The anterior band is attached to the joint capsule, condylar head, and superior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle, whereas the posterior band attaches to the bilaminar zone or retrodiscal tissue, which is a rich neurovascular tissue. The bilaminar zone, also known as the posterior ligament , provides stability to the disc by attaching the posterior band of the disc to the mandibular condyle and the temporal bone (see Fig. 1 ).

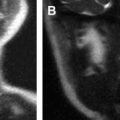

MR Imaging

On sagittal MR imaging, the normal disc appears as a biconcave structure with homogenous low signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging. Rarely, bright signal can be seen within the intermediate zone on T2-weighted imaging, resembling a centrally hydrated disc. The fibrofatty bilaminar zone, or retrodiscal tissue, has a higher signal intensity than muscle on proton density and T1-weighted sequences. More fibers of the posterior attachment with intermediate signal intensity are seen extending from the superior aspect of the posterior band of the disc to attach to the temporal bone, and another band originates from the inferior aspect of the posterior band and attaches to the condylar neck ( Fig. 2 ).

Normal anatomy

The TMJ is an unusual synovial joint in that the articular surfaces are covered with fibrocartilage rather than hyaline cartilage. The articular capsule is attached to the edges of the glenoid fossa, including the articular tubercle, and to the neck of the mandible. The fibrocartilaginous articular disc, or meniscus, lies within the articular capsule between the mandibular condyle and glenoid fossa, dividing the synovial cavity into superior and inferior synovial compartments ( Fig. 1 ). The lateral pterygoid muscle inserts anteriorly on the mandibular condyle at the pterygoid fovea and the anterior band of the disc. The articular disc, or meniscus, is a biconcave avascular connective tissue structure composed of three segments: anterior band, intermediate zone, and posterior band.

The anterior and posterior bands are triangular in shape and connected by the thin intermediate zone. The anterior band is attached to the joint capsule, condylar head, and superior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle, whereas the posterior band attaches to the bilaminar zone or retrodiscal tissue, which is a rich neurovascular tissue. The bilaminar zone, also known as the posterior ligament , provides stability to the disc by attaching the posterior band of the disc to the mandibular condyle and the temporal bone (see Fig. 1 ).

MR Imaging

On sagittal MR imaging, the normal disc appears as a biconcave structure with homogenous low signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging. Rarely, bright signal can be seen within the intermediate zone on T2-weighted imaging, resembling a centrally hydrated disc. The fibrofatty bilaminar zone, or retrodiscal tissue, has a higher signal intensity than muscle on proton density and T1-weighted sequences. More fibers of the posterior attachment with intermediate signal intensity are seen extending from the superior aspect of the posterior band of the disc to attach to the temporal bone, and another band originates from the inferior aspect of the posterior band and attaches to the condylar neck ( Fig. 2 ).

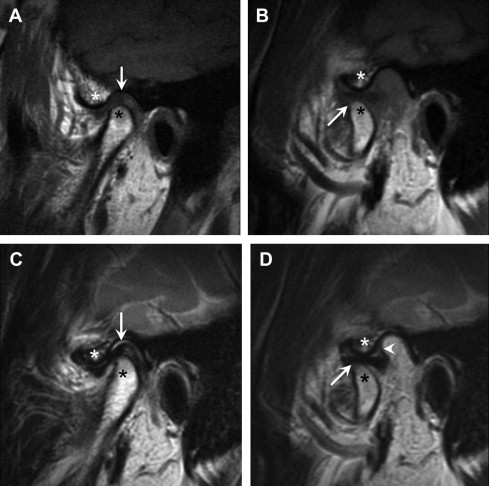

Normal biomechanics

The TMJ is primarily a hinge and glide articulation, but also allows side-to-side motion. The muscles of mastication are responsible for the opening and closing of the jaw. The temporalis, medial pterygoid, and masseter muscles facilitate jaw closure. The lateral pterygoid contributes to jaw opening. In a normal joint in the closed mouth position, the disc is positioned between the condylar head inferiorly, the glenoid fossa superiorly, and the articular eminence anteriorly. The disc is often sigmoid-shaped and lies in the anterior half of the joint space (see Fig. 2 C). In the closed mouth position, the junction of the posterior band and bilaminar zone should lie immediately above the condylar head near the 12 o’clock position ( Fig. 3 ). The junction of the posterior band and bilaminar zone should fall within 10° of vertical to be within the 95th percentile of normal. However, controversy exists over this definition of normal versus abnormal, because this definition results in anterior displacement in a large number of asymptomatic volunteers (33%). Rammelsberg and colleagues suggested that a disc should be considered anteriorly displaced beyond 30° from the vertical. At Emory, the term partial anterior displacement is used to describe discs that do not fall within 10° from the 12 o’clock position, but rather lie around the 10 to 11 o’clock position.

During jaw opening, two motions occur at the TMJ. First, rotation occurs around a horizontal axis through the condylar heads. The second motion is anterior translation of the condyle and disc to a position beneath the articular eminence. The disc slides into a position between the condylar head and articular eminence and takes on a more “bow tie” appearance (see Fig. 2 D; Fig. 4 ). The loose tissue of the bilaminar zone allows a remarkable range of motion of the disc. In the open mouth position, the disc rotates posteriorly on the condyle and the entire complex moves anteriorly.

On coronal images, the medial and lateral borders of the disc are aligned with the condylar head and do not bulge medially or laterally.

MR imaging protocol

MR imaging is the standard imaging choice for evaluating the TMJ for internal derangement. The authors’ TMJ imaging is performed with a standard noncontrast protocol that includes static and cine imaging in open and closed mouth positions ( Table 1 ). Dual-surface coils are used to provide excellent detail of the joint with a small field of view and high signal-to-noise ratio.

| # | Sequence | Plane | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T1: TR 500, TE min, 3 mm, 0.5 skip | COR | Closed mouth |

| 2 | T1: TR 500, TE min, 2 mm, 0 skip | AX | Closed mouth |

| 3 | T2 & PD, TR 3500, TE min & 85 | Left SAG OBL | Closed mouth |

| 4 | T2 & PD, TR 3500, TE min & 85 | Right SAG OBL | Closed mouth |

| 5 | T2 & PD, TR 3500, TE min & 85 | LEFT SAG OBL | Open mouth |

| 6 | T2 & PD, TR 3500, TE min & 85 | Right SAG OBL | Open mouth |

| 7 | T2, TR 1180, TE 64, cine | Left SAG OBL | Dynamic |

| 8 | T2, TR 1180, TE 64, cine | Right SAG OBL | Dynamic |

Coronal and axial T1-weighted images are routinely obtained to exclude other pathologies in the masticator space and to evaluate the contour and marrow signal of the mandibular condyles. Additionally, the coronal images are needed to identify lateral or medial disc displacement. The oblique or parasagittal images are corrected sagittal images (approximately 30° from the true sagittal) that are scanned in a plane perpendicular to the horizontal long axis of the mandibular condyle. The authors do not routinely use intravenous contrast for TMJ imaging, although early reports suggested that gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images with fat saturation may improve detection of disruption or injury to the posterior disc attachment. Dynamic information can be obtained with MR imaging by acquiring static images with spin echo techniques at progressive increments from closed to open position and then displaying the images sequentially in a back-and-forth closed cine loop. Other authors have also described using a balanced steady-state free procession sequence at 3T for dynamic MR imaging of the TMJ.

Although MR is the preferred imaging study for internal derangement of the TMJ, CT may be complementary to MR for evaluating inflammatory arthritis, infection, or tumors. CT may also be complementary in the setting of coexistent internal derangement and osteoarthritis ( Box 1 ).

- •

Internal derangement: MR is the primary imaging modality

- •

Osteoarthritis (often complication of internal derangement): MR and CT may be complimentary

- •

Infection: MR and CT may be complementary

- •

Tumor: MR and CT may be complementary

- •

Inflammatory arthritis: MR and CT may be complementary

- •

Trauma: CT is the primary imaging modality

Internal derangement

The most common abnormality of the TMJ is internal derangement, which is an abnormal relationship of the disc with respect to the mandibular condyle, articular eminence, and glenoid fossa. The incidence of symptomatic internal derangement peaks in the second to fourth decade of life, with a female-to-male ratio of 3:1. Patients most often present with jaw pain on biting and opening, clicking and locking when opening or closing, and decreased maximum incisal opening. Headaches and myofascial pain may occur secondarily or be unrelated to the internal derangement. Internal derangement is considered an acquired, progressive degenerative process. Wilkes classified various stages of internal derangement, progressing from an early stage with only reciprocal clicking and no pain, to a late stage characterized by pain, restriction of motion, and grinding symptoms. In the earliest stages, only mild anterior displacement of a morphologically normal disc is present in the closed mouth position, whereas the late stage is characterized by anterior displacement without recapture of a thinned disc with perforation and arthritic changes ( Box 2 ). It is important to understand the Wilkes staging system, because many TMJ surgeons use this system to classify and treat patients.