Musculoskeletal Neoplasms

Thomas H. Berquist

Mark J. Kransdorf

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Imaging Approaches

Key Facts

Imaging studies are essential for detecting, characterizing, and staging bone lesions.

Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and radionuclide scans all play a role. Angiography is useful for evaluating tumor vascularity and for preoperative embolization.

Effectiveness of imaging studies for evaluating features of bone tumors is as follows:

Radiographs

CT

MRI

Radionuclide Scans

Lesion morphology

Thin cortical bone

Lesion extent

Early detection in marrow and soft tissues

Site (cortical, marrow, diaphysis, metaphysis, epiphysis)

Bone destruction or production

Joint space involvement

Skip lesions

Bone production or destruction

Periosteal response

Marrow edema patterns

Metastasis

Periosteal response

Calcifications/matrix

Cortical destruction

Soft tissue calcification or ossifications

Trabecular destruction

Suggested Reading

Greenfield GB, Arrington JA. Imaging of bone tumors: A multimodality approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1995.

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Radiographic Features

Key Facts

Routine radiographs provide vital and fundamental information regarding tumors and tumorlike conditions of bone. Key features are as follows:

Patterns of bone destruction:

Geographic: least aggressive. Margins may be sclerotic, well defined without sclerosis, or ill defined.

Moth-eaten: more aggressive, less well defined. Longer zone of transition. Seen with malignant lesions and osteomyelitis.

Permeative: most aggressive with more rapid destruction. Margins not defined. Seen with Ewing sarcoma, aggressive malignancies, and infections.

Bone formation

Matrix—calcification or ossification

Trabeculation—seen with giant cell tumors, chondromyxoid fibroma, aneurysmal bone cyst, hemangioma, nonossifying fibroma

Cortical penetration

Periosteal response

Soft tissue mass

Distribution:

Central, eccentric, cortical, juxtacortical

Diaphyseal, metaphyseal, epiphyseal

Skeletal location (e.g., tibia and calcaneus)

FIGURE 10-2 Moth-eaten. Lateral view of the femur showing a destructive lesion with poorly defined margins and a pathologic fracture anteriorly (arrowhead) as the result of metastasis. |

FIGURE 10-3 Permeative. Poorly defined lytic lesion in the proximal humerus with permeative cortical changes attributable to Ewing sarcoma. |

FIGURE 10-5 Periosteal response. Osteogenic sarcoma with bone sclerosis and cortical break: a triangular elevation (arrow) (Codman triangle) seen with aggressive lesions. |

Suggested Reading

Greenspan A, Remagen W. Differential diagnosis of tumors and tumorlike lesion of bone and joints. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:1–24.

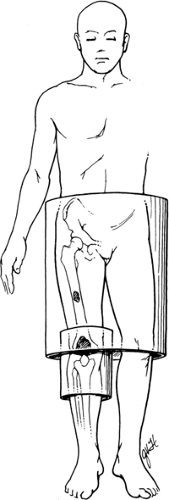

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Protocols

Key Facts

MRI of bone tumors is approached somewhat differently compared with other indications.

The field of view needs to include a larger area to evaluate adjacent joints and to avoid overlooking skip lesions.

Image planes, especially for long bones, should be selected to demonstrate the osseous structure on one image.

Coil selected should be large enough to cover the needed anatomic area.

Pulse sequences typically include axial T1- and T2-weighted spin-echo MR images. We prefer conventional T2 images to turbo T2 or fat-suppressed turbo T2 images.

Contrast enhancement is used routinely.

Suggested Reading

Kransdorf MJ, Berquist TH. Musculoskeletal neoplasms. In: Berquist TH, ed. MRI of the musculoskeletal system, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:802–915.

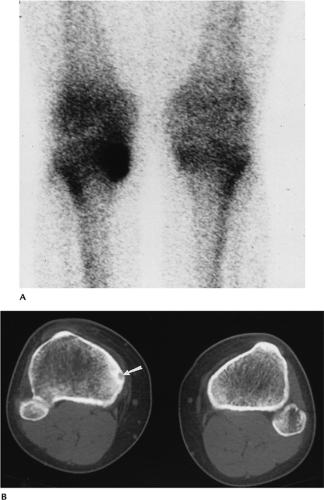

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Osteoid Osteoma

Key Facts

Clinical:

Osteoid osteoma is a relatively common lesion accounting for 12% of benign bone tumors. Patients present with pain, worse at night, often relieved by anti-inflammatory medications (75%).

Age: 5 to 35 years, peak second decade

Sex: Males outnumber females 3:1.

Common locations: majority in lower extremity; proximal femur, femoral neck

Three types of osteoid osteoma:

Cortical: most common. Fusiform cortical thickening with a lucent nidus. May contain central calcification.

Cancellous: femoral neck and small bones of the hand, foot, and posterior elements of the spine.

Subperiosteal: least common. Arise in soft tissue adjacent to bone.

Imaging features:

Radiographic features: small round lucent area, usually in cortex with surrounding sclerosis. May have central calcification or ossification.

CT: technique of choice for detection and characterization.

MRI: small focal lesion with bone and soft tissue edema on T2-weighted or short T1 inversion recovery (STIR) images. Subtle lesions enhance with dynamic contrast studies.

Differential diagnosis:

Brodie abscess

Osteoblastoma

Stress fracture

Treatment: complete resection of nidus; percutaneous radiofrequency ablation.

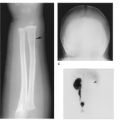

FIGURE 10-9 Tibial osteoid osteoma. (A) Posterior image from a bone scan showing increased tracer in the medial tibia. (B) CT scan clearly defines the nidus (arrow) and surrounding bone sclerosis. |

Suggested Reading

Assorin J, Richardi G, Railhec JJ, et al. Osteoid osteoma. MR imaging versus CT. Radiology 1994;191:217–233.

Greenspan A. Benign bone forming lesions: Osteoma, osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma. Skel Radiol 1993;22:485–500.

Liu PT, Chivers FS, Roberts CC, et al. Imaging of osteoid osteoma by dynamic gadolinium-enhanced imaging. Radiology 2003;277:691–700.

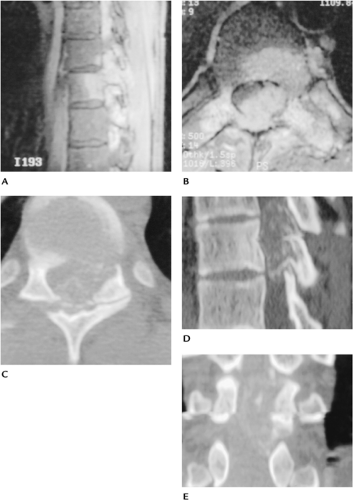

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Osteoblastoma

Key Facts

Clinical:

Osteoblastomas account for 3.5% of benign bone tumors. Patients present with chronic local pain.

Age: any age, most common second decade

Sex: Males outnumber females 3:1.

Common locations: vertebrae (42.5%), posterior elements most commonly involved

Imaging features:

Radiographic features: May be similar to osteoid osteoma, but larger (>1.5 cm). May have malignant appearance. Bone expanded; 55% have an ossified matrix.

CT: cortical expansion, ossified matrix

MRI: variable, not well defined

Differential diagnosis:

Osteoid osteoma

Aneurysmal bone cyst

Osteosarcoma

Treatment: en bloc resection, bone grafting

Suggested Reading

McLeod RA, Dahlin DC, Beabout JW. The spectrum of osteoblastoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1976;126:321–335.

Unni KK. Dahlin’s bone tumors: General aspects and data on 11,087 cases. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:131–142.

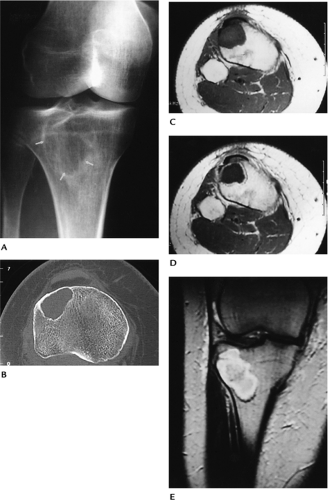

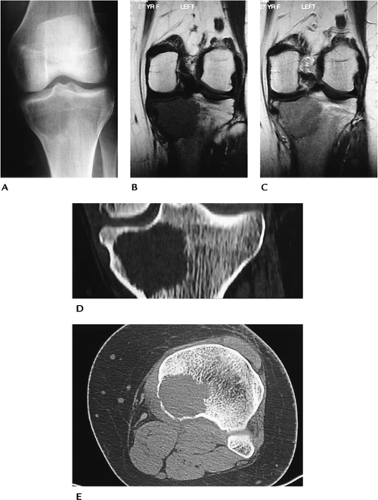

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Osteochondroma

Key Facts

Clinical:

Osteochondromas are the most common accounting for 35% of benign skeletal neoplasms. Patients present with a palpable mass that may be painful.

Age: 5 to 50 years, peak second decade

Sex: Males outnumber females 2:1.

Common locations: distal femur, proximal tibia, proximal humerus

Imaging features:

Radiographic features: bony projection with contiguous marrow and cortex from bone of origin

CT: similar to radiograph. Cartilaginous cap more easily appreciated (normal cap thickness <1.5–2 cm).

MRI: cartilage cap low intensity on T1-weighted and high intensity on T2-weighted sequences. Other features similar to radiographs.

Differential diagnosis:

Usually characteristic

Myositis ossificans

Treatment: Observe unless symptoms or cosmetic deformity, then resect.

Suggested Reading

Unni KK. Dahlin’s bone tumors: General aspects and data on 11,087 cases, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:11–24, 121–130, 355–432.

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Enchondroma

Key Facts

Clinical:

Enchondromas account for 13.4% of benign bone tumors. Most are asymptomatic. If painful, low-grade chondrosarcoma should be excluded. Chondrosarcomas have more intense uptake on radionuclide scans and typically erode two thirds of the cortical thickness. There may also be periosteal reaction and a soft tissue mass.

Age: all age groups, 55% in the second through fourth decades

Sex: no sex predilection

Common locations: small bones of hand and feet (50%) with 87% in the hand, proximal femur, and humerus

Imaging features:

Radiographic features: medullary with sharp margins. Calcification common. May be multiple.

CT: well-defined lesion with central calcified matrix. Cortical erosion easily measured.

MRI: lobulated low intensity on T1-weighted and high intensity on T2-weighted images. Useful for differentiating enchondroma from chondrosarcoma. Mineralized areas show decreased signal intensity on all pulse sequences.

Differential diagnosis:

Bone infarct

Chondrosarcoma

Treatment: Observe. Curettage and bone graft if symptomatic.

FIGURE 10-13 AP (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of a phalangeal enchondroma. There is cortical expansion and a pathologic fracture (arrow). |

Suggested Reading

Murphy MD, Flemming DJ, Boyea SR, et al. Enchondroma vs. chondrosarcoma in the appendicular skeleton: Differentiating features. Radiographics 1998;18:1213–1237.

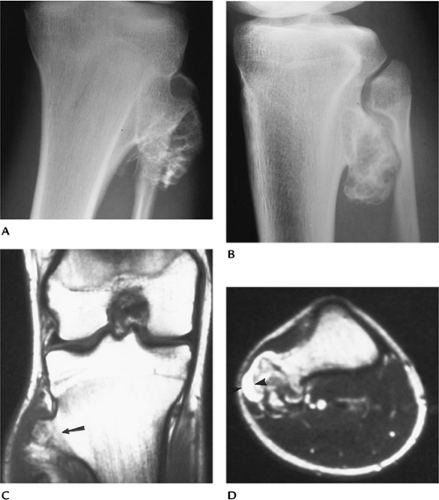

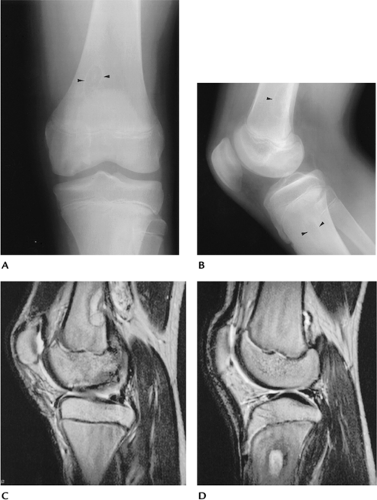

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Chondroblastoma

Key Facts

Clinical:

Patients present with chronic local pain.

Age: 90% occur from 5 to 25 years of age, approximately 70% in second decade.

Sex: Males outnumber females 2–3:1.

Common locations: epiphyseal with 40% in the knee and 16% in the proximal humerus

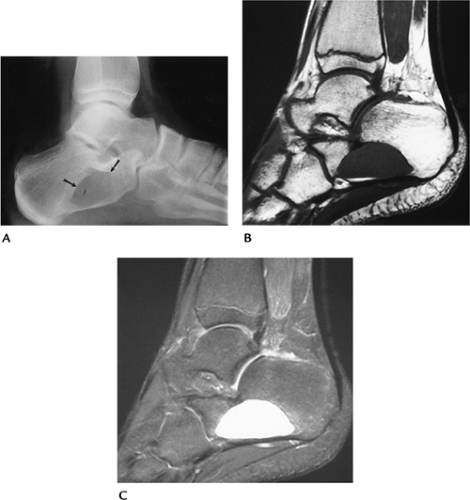

Imaging features:

Radiographic features: epiphyseal location. Sharp margins with sclerotic rim. Calcification in approximately 50% to 60%.

CT: well-defined lesion with sclerotic margins and, frequently, central calcification

MRI: well-defined low-intensity lesion on T1-weighted and variably high signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences, with extensive surrounding edema in the majority of cases

Differential diagnosis:

Giant cell tumor

Avascular necrosis

Clear cell chondrosarcoma

Treatment: curettage and bone grafting

Suggested Reading

Unni KK. Dahlin’s bone tumors: General aspects and data on 11,087 cases. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:47–57.

Weatherall PT, Moole GE, Mendelsohn DB, et al. Chondroblastoma: Classic and confusing appearance at MR. Radiology 1994;190:467–474.

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Chondromyxoid Fibroma

Key Facts

Clinical:

Patients present with local pain and swelling.

Age: 5 to 50 years, most common (55%) in the second and third decades

Sex: slightly more common in males

Common locations: metaphysis of the knee and distal tibia

Imaging features:

Radiographic features: eccentric metaphyseal lesion with well-defined sclerotic margins. Calcifications seen in 12%, more common in those aged more than 40 years.

CT: eccentric metaphyseal lesion with well-defined sclerotic margins. Calcifications easily appreciated

MRI: well-defined lesion with uniform low intensity on T1-weighted and high or intermediate intensity on T2-weighted sequences

Differential diagnosis:

Fibrous defect

Fibrous dysplasia

Chondroblastoma

Aneurysmal bone cyst

Treatment: curettage and bone grafting

Suggested Reading

Rahimi A, Beabout JW, Ivens JC, et al. Chondromyxoid fibroma: A clinicopathological study of 76 cases. Cancer 1972;30:726–736.

Yamaguchi T, Dorfman HD. Radiographic and histologic patterns of calcification in chondromyxoid fibroma. Skel Radiol 1998;27:559–564.

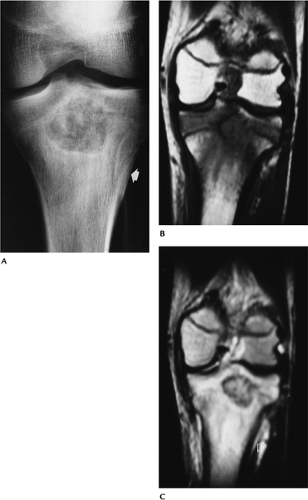

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Nonossifying Fibroma

Key Facts

Clinical:

Nonossifying fibroma, fibrous cortical defect, and fibroxanthoma describe similar metaphyseal lesions. Lesions are common and typically discovered incidentally.

Age: 5 to 35 years, peak second decade

Sex: No sex predilection.

Common locations: distal femur, distal tibia

Imaging features:

Radiographic features: well-defined eccentric lytic defect with scalloped sclerotic margins in the metaphysis of a long bone

CT: well-defined eccentric lytic defect with scalloped sclerotic margins in the metaphysis of a long bone

MRI: well-defined cortical lesion with low to intermediate intensity on T1-weighted and low to intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences

Differential diagnosis:

Fibrous dysplasia

Chondromyxoid fibroma

Eosinophilic granuloma

Treatment: none unless potential for pathologic fracture

Suggested Reading

Jee W, Choe B, Kang H, et al. Nonossifying fibroma. Characteristics at MR imaging with pathologic correlation. Radiology 1998;209:197–202.

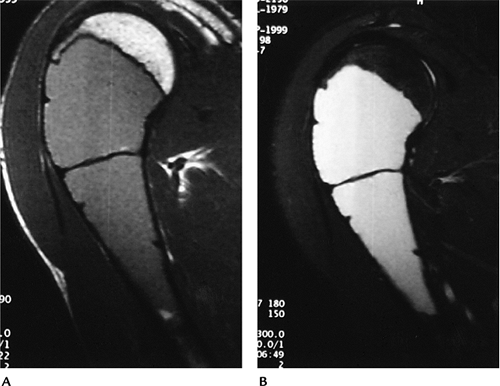

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Bone Cyst

Key Facts

Clinical:

Patients are asymptomatic unless pathologic fracture occurs.

Age: first two decades

Sex: Males outnumber females 3:1.

Common locations: proximal humerus, femur, or tibia (90% in humerus or femur)

Imaging features:

Radiographic features: well-defined lytic lesion frequently near the physis. May be septated. If fracture has occurred, the “fallen fragment sign” (bone fragment in the dependent portion of the cyst) is virtually pathognomonic.

CT: fluid density, well-defined lesion with bony septations

MRI: uniformly low intensity on T1-weighted and high intensity on T2-weighted sequences. Fluid–fluid level or “fallen fragment” after fracture.

Differential diagnosis:

Aneurysmal bone cyst

Fibrous dysplasia

Treatment: aspiration and steroid injection. If in a weight-bearing region, consider curettage and bone grafting.

FIGURE 10-18 Unicameral bone cyst. AP radiograph of the humerus with a bone cyst and pathologic fracture with the “fallen fragment sign” (arrows). |

Suggested Reading

Conway WF, Hayes CW. Miscellaneous lesions of the bone. Radiol Clin North Am 1993;31:299–323.

Kileen K. The fallen fragment sign. Radiology 1998;207:261–262.

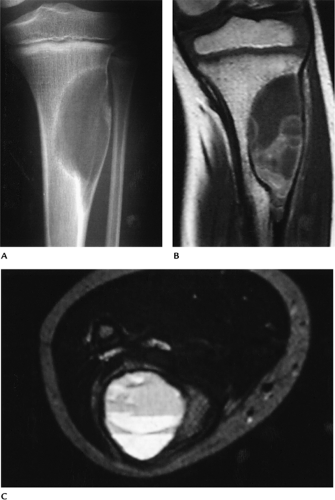

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

Key Facts

Clinical:

Patients present with pain.

Age: 5 to 35 years, 80% in the first two decades

Sex: Females slightly outnumber males.

Common locations: more than 50% in the long bones; 12% to 30% in the spine

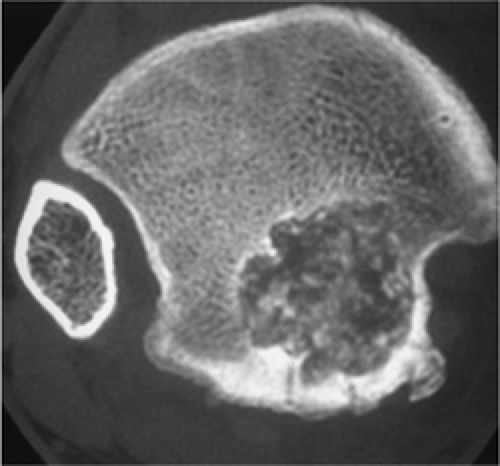

Imaging features:

Radiographic features: eccentric lytic lesion with expanded or “ballooned” bony contour. Sclerotic rim and periosteal response are common.

CT: same features as radiographs but fluid density

MRI: well-defined lesion with high signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences. Fluid–fluid levels are common.

Differential diagnosis:

Bone cyst

Giant cell tumor

Osteoblastoma (vertebral location)

Treatment: curettage and bone grafting

Suggested Reading

Munk PL, Helms CA, Holt RG, et al. MR imaging of aneurysmal bone cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1989;153:99–101.

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Fibrous Dysplasia

Key Facts

Clinical:

Typically asymptomatic. Abnormal bone growth may cause deformity. Lesions may be single (monostotic) in which case the femur, tibia, ribs, and skull base are most commonly involved. Multiple lesions (polyostotic) involve one side of the skeleton in 90% of patients. These lesions are more often symptomatic and may enlarge until skeletal maturity.

Associated syndromes:

Mazabraud syndrome: fibrous dysplasia and multiple intramuscular myxomas

Albright-McCune: females with polyostotic dysplasia, skin lesions, and precocious puberty

Age: most often second or third decade

Sex: slightly more common in females

Common locations: skull, mandible, ribs, femoral neck, tibia

Imaging features:

Radiographic features: metaphyseal or diaphyseal lytic or “ground glass” density with sharp margins and bone expansion. May affect multiple bones in approximately 15% of patients. “Long lesion in long bone.”

CT: well-defined lesion with sclerotic margins

MRI: well-defined lesion with low-intensity margins. Low signal intensity on T1-weighted and intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences.

Differential diagnosis:

Nonossifying fibroma

Bone cyst

Aneurysmal bone cyst

Chondromyxoid fibroma

Treatment: observation

Suggested Reading

Campanacci M, Laus M. Osteofibrous dysplasia of the tibia and fibula. J Bone Joint Surg 1981;63A:367–375.

Gober GA, Nicholas RW. Case report 800. Skeletal fibrous dysplasia associated with intramuscular myxomas (Mazabraud’s syndrome). Skel Radiol 1993;22:452–455.

Greenspan A, Remagen W. Differential diagnosis of tumors and tumorlike lesions in bone and joints. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:215–223.

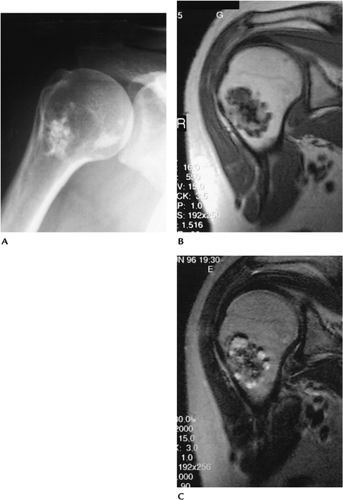

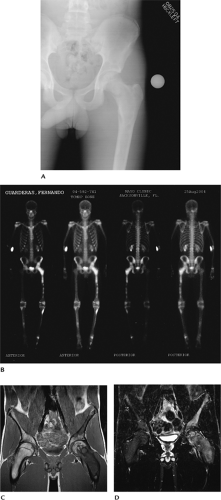

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Giant Cell Tumor

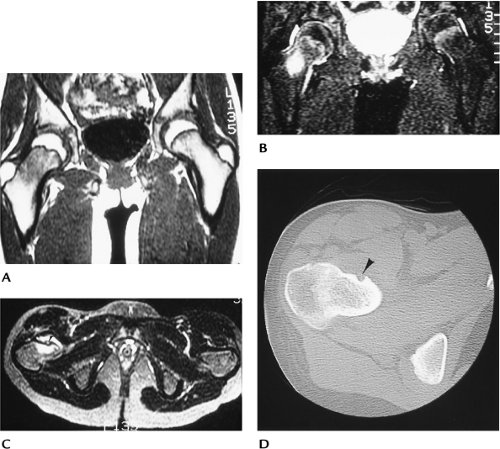

Key Facts

Clinical:

Giant cell tumors account for 22.7% of benign bone tumors. Patients present with pain and swelling in the involved site. A tender palpable mass commonly present.

Age: 20 to 40 years

Sex: Females affected slightly more frequently than males.

Common locations: most involve the distal femur or proximal tibia (46%) followed by the distal radius and sacrum. Epiphyseal location.

Imaging features:

Radiographic features: lytic lesion with nonsclerotic margins originating in the metaphysis but extending to subchondral bone. Cortical breakthrough in 33% to 50% of cases.

CT: similar to radiographs. No tumor matrix.

MRI: low intensity on T1-weighted and intermediate signal on T2-weighted sequences. T2 sequences may show decreased signal because of hemosiderin deposition. In some cases, signal intensity increased on T2-weighted images. May have fluid–fluid levels. Enhanced on post-contrast images.

Differential diagnosis:

Chondroblastoma

Osteosarcoma

Fibrosarcoma

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

Treatment: resection with grafting or, in some cases, joint prosthesis

Suggested Reading

Aoki J, Tanikawa H, Ishü K, et al. MR findings indicative of hemosiderin in giant-cell tumor of bone: Frequency, cause, and diagnostic significance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;166:145–148.

Bone Tumors/Tumorlike Conditions: Eosinophilic Granuloma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree