Case presentation

A 5-year-old male is brought for right elbow pain and swelling after falling while playing on the monkey bars at school. The fall was witnessed by several teachers and friends, who reported no loss of consciousness or other injuries. He complains of right elbow pain but denies neck or back pain. His physical examination is remarkable for impressive right elbow swelling and pain. He is grossly neurovascularly intact and there is no other apparent injury.

Imaging considerations

Plain radiography

Proper evaluation of suspected supracondylar fractures requires anterior-posterior and lateral views of the elbow. , The lateral view is obtained with the elbow in flexion at a true 90-degree angle, or at least as close to this as possible. , Oblique views are not typically required but can be used to further identify minimally displaced fractures if there is strong clinical suspicion for a fracture. The clinician should bear in mind the possibility of additional associated fractures with a supracondylar fracture. Associated fractures of the wrist and forearm are most common, but fractures of the proximal humerus or clavicle also occur. Therefore, when a supracondylar fracture is present, one should have a low threshold to image other sites of clinical concern, such as the wrist or forearm, when clinically indicated by physical examination, or when physical examination is difficult, especially in young children. ,

There are several key elements to address when evaluating a plain radiograph for supracondylar fractures, as not all are readily evident. The lateral view is particularly important for this purpose:

| ELEMENT | COMMENTS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a The anterior humeral line in children: when <4 years can pass through the anterior third (31%), middle third (52%), or posterior third (18%) of the capitellum without any pathology. ,

The elbow fat pads are an important element, as they may be the only indication of a fracture. Fat pads may be seen in either a posterior location or anterior location. , The posterior fat pad is always associated with a joint effusion when it is seen on the lateral view with the elbow flexed (hence the importance of the 90-degree lateral elbow radiograph). , The presence of a posterior fat pad is associated with an occult elbow fracture in 76% of cases when no fracture is identified on the initial radiographs. The presence of a posterior fat pad is not exclusive to supracondylar fractures, however. One series reported that the presence of a posterior fat pad was associated with a supracondylar fracture in 53% of cases, proximal ulna in 26% of cases, lateral condyle in 12% of cases, or radial-neck in 9% of cases. The anterior fat pad is normally visualized on a lateral flexed elbow view but can be elevated due to the presence of an elbow joint effusion.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography has the advantage of lacking ionizing radiation and general availability, but skill is required in order to produce a meaningful study. This modality has a reported sensitivity of up to 96% and specificity up to 90% for detecting pediatric elbow fractures when performed by providers in the emergency setting who are specifically trained in sonographic musculoskeletal imaging.

Computed tomography (CT)

Routine use of CT is not indicated for suspected pediatric supracondylar fractures. However, this modality has excellent sensitivity and specificity for the detection of these injuries. , CT may be utilized if there is a complex injury but subspecialty consultation is appropriate prior to obtaining such a study.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Routine use of MRI is not indicated for suspected pediatric supracondylar fractures. This imaging modality does have the ability to detect soft tissue and cartilage injuries. ,

Imaging findings

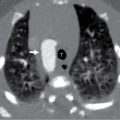

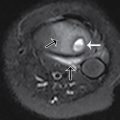

After administration of intranasal fentanyl, plain radiography is obtained of the elbow and the forearm. Selected images are seen here, demonstrating a severely displaced supracondylar fracture ( Figs. 52.1 and 52.2 ).

Case conclusion

Pediatric Orthopedics was consulted to evaluate the patient, who was placed in a posterior long arm splint without any attempt at reduction. He was taken to the operating suite several hours later for closed reduction and percutaneous pinning of the fracture and recovered without complications.

Supracondylar fractures are common in the pediatric population, representing 3% of all fractures. , The usual mechanism of injury is a fall from an outstretched arm and can result from extension and flexion injuries, with the majority being extension-type injuries. , , Extension injuries are classified according to the Gartland Classification System ( Fig. 52.3 ), which classifies these fractures based on the degree of fracture displacement seen on the lateral view plain radiograph: ,

| GARTLAND TYPE | FINDINGS | STABLE? | MANAGEMENT |

| I | Minimal (<2 mm) to no displacement Intact anterior humeral line | Yes | Conservative—immobilization for 3–4 weeks |

| II | Slight displacement (>2 mm) with a posterior angulation of the distal fragment Anterior humeral line does not bisect the capitellum correctly Intact posterior cortex | Maybe | Controversial |

| III | Posteromedial or posterolateral displacement of the distal fragment Loss of integrity of the posterior cortex | No | Closed reduction and fixation with K wires |

| IV | No specific radiographic findings but multidirectional instability noted during surgical reduction. | No | Operative technique varies |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree