Joseph J. Zechlinski • William S. Rilling

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) represent a broad spectrum of tumors arising from neuroendocrine (NE) cells throughout the body, often secreting peptides which cause characteristic hormonal syndromes. Classically, this manifests as diarrhea, flushing, wheezing, abdominal cramping, and/or peripheral edema, the constellation of symptoms known as carcinoid syndrome. In contrast, most pancreatic NETs (pNETs) are nonfunctioning, although they can secrete various peptide hormones and are named as such, including insulinoma, gastrinoma, glucagonoma, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIPoma).

NE carcinoma was classically described as a more indolent neoplasm; however, tumor biology is variable and can be aggressive. To this point, a large proportion of patients with NETs have liver metastases at the time of diagnosis and often have a high disease burden, with only 10% of patients being candidates for surgical resection at presentation.1 These patients have the best chance for long-term survival following surgical resection, with 5-year survival approaching 60% to 80%.2 In contrast, chemotherapy generally has a more limited role, with disease control lasting only 8 to 10 months.3 Given this disparity, various other treatment modalities are employed in the multidisciplinary care of NETs, including liver-directed therapies and targeted molecular therapies.

CLASSIFICATION

Traditionally considered a rare neoplasm, analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database in contemporary reviews reveals that NETs have a similar incidence as testicular cancer, cervical cancer, multiple myeloma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and cancers of the central nervous system. Furthermore, the prevalence of NETs is increasing—365% in the last 30 years—now being more common than esophageal cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, and hepatobiliary cancer in the United States.4,5

NETs can arise from many tissues in the body, but gastrointestinal, pancreatic, lung, and thymic origins have been most extensively studied with regard to classification. Several systems exist, with the World Health Organization (WHO) classification most commonly used for tumors of the gastrointestinal tract.6 Recently updated in 2010, it divides NETs into low grade, NE neoplasm grade 1; intermediate grade, NE neoplasm grade 2; and high grade, NE carcinoma grade 3. Tumor differentiation, referring to the histologic similarity of the tumor to the tissue of origin, and tumor grade, based on mitotic count and Ki 67 index (a measure of proliferative rate), are principle determinants of tumor aggressiveness and act as prognostic factors. Generally, high-grade tumors have an elevated mitotic rate (>10 to 20 mitoses per 10 high-power fields), high Ki 67 index (>20%), extensive necrosis, and pleomorphism.7 Staging is based on the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) system, using cytologic grade, proliferative index (Ki 67), tumor size, degree of metastases, and the primary site.

CURATIVE TREATMENTS

Surgical resection and/or intraoperative ablation offers the best curative treatment for neuroendocrine liver metastases (NLMs), with 5-year survival estimated at 70.5% for resectable lesions based on a recent systematic review.8 Aggressive pursuit of the primary tumor is a critical part of the surgical treatment algorithm. The goal of curative surgery is a macroscopically complete (R0/R1) resection and/or ablation. Palliative surgical “debulking” is somewhat controversial and may be considered appropriate if greater than 90% of the tumor burden can be resected or surgically ablated.9,10 Despite the demonstrated survival benefit, disease recurrence is extremely common following resection and/or intraoperative ablation. In a recent review of 339 patients, 94% had recurrent disease at 5 years.11 Survival can be improved with liver-directed therapies performed in patients with progressive disease following initial resection.12 As stated earlier, a minority (~10%) of patients are candidates for resection at initial presentation.2 For the remaining majority of patients, liver-directed therapies and/or systemic and targeted molecular therapies are considered.

Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is a potential curative treatment of NLMs; however, prognosis is worse relative to all other liver transplant recipients (5-year survival 57.8% vs. 74% among 185 patients transplanted in the United States),1 and postoperative mortality is relatively high. Similar data were observed in a European series of 103 patients across 23 institutions (overall survival of 47% and recurrence-free survival of 24% at 5 years).13 Nevertheless, some centers will consider patients with NLMs for transplantation.

Systemic and Targeted Molecular Therapies

Systemic chemotherapy has varied success in the treatment of NLMs and depends on primary tumor site and histologic tumor grade. Regimens for well-differentiated pNET generally include combinations of streptozotocin, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). Midgut NET has been treated with similar regimens with the addition of cyclophosphamide, and etoposide/cisplatin has been studied in poorly differentiated gastroenteropancreatic NET.3 Systemic chemotherapy for carcinoid tumors has been less successful.

Somatostatin analogues (SSA) have been used extensively, especially for symptom control. Many other targeted therapies are under review, acting on the mTOR, VEGF, EGFR, IGF-1R, histone deacetylase, protein degradation, immunomodulating, c-kit, and PDGFR pathways.14 To date, bevacizumab, sunitinib, and everolimus are the most promising available agents and have been studied in phase III clinical trials.15

Somatostatin functions as an inhibitor of endocrine activity, reducing portal venous blood flow, decreasing gastrointestinal secretions, inhibiting peristalsis, and downregulating gastrointestinal hormone production. Native human somatostatin peptides have a short half-life of approximately 1 minute,16 but synthetic analogues have been developed with half-lives of 2 hours—chiefly among these are octreotide and lanreotide. These work exceptionally well for symptom control and reduction of urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid levels17–21 and also have antiproliferative effects. Side effects are generally mild, including nausea, bloating, and steatorrhea.7 The PROMID study, a randomized phase III trial using octreotide long-acting repeatable (LAR) versus supportive care in gastroenteropancreatic NETs, reported a median time to progression of 14.3 months for octreotide versus 6 months for placebo (P = .000072), but there was no significant difference in survival.22 Additionally, this benefit was most pronounced in patients with low tumor burden, well-differentiated tumors, and resected primary tumor.

The mTOR inhibitors temsirolimus and everolimus have been studied in NETs. In the RADIANT 1 trial, everolimus monotherapy (n = 115) had a response rate and median progression-free survival (PFS) of 9% and 9.7 months, respectively, and everolimus plus octreotide (n = 45) demonstrated a 4% response rate and PFS of 16.7 months.23 In a subsequent phase III trial of metastatic functional carcinoid tumors (RADIANT 2), increased PFS of 16.4 months versus 11.3 months was observed when 10 mg oral everolimus daily was added to 30 mg intramuscular octreotide LAR every 28 days, compared to octreotide LAR alone. This result was borderline significant (P = .026).24 The RADIANT 3 trial randomized 410 patients with PNETs to everolimus versus supportive care, showing PFS of 11.0 months versus 4.6 months for placebo.25

Inhibition of the VEGF pathway has been promising, as increased circulating levels of VEGF are associated with NET progression. A monoclonal antibody to VEGF, bevacizumab, showed a 95% PFS at 18 weeks versus 68% for pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN).26 Another agent, sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitor, was also studied in patients with PNET. This phase III study including 171 patients demonstrated median PFS of 11.4 months versus 5.5 months, favoring sunitinib 37.5 mg daily to placebo.27

Liver-Directed Transarterial Therapies

Interventional approaches to NET include but are not limited to transarterial techniques of tumor embolization and radioembolization. Embolization can be further subdivided into transarterial embolization (TAE), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), and drug-eluting bead chemoembolization (DEB-TACE). NETs are typically hypervascular within the liver, receiving greater than 90% of their blood supply from the hepatic artery, compared to normal liver parenchyma which receives 75% to 80% of its blood supply from the portal vein and only 20% to 25% from the hepatic artery.28–30 This provides a rationale for embolic, chemoembolic, or radioembolic material to concentrate with hepatic metastases when administered via selective or superselective catheter angiography. Liver-directed therapies are generally indicated for patients with symptomatic unresectable disease. The timing of integrating liver-directed therapy in asymptomatic patients is somewhat controversial, but given the high response rates in general, many centers favor integrating liver-directed therapies earlier in the disease course.

Hepatic Arterial Embolization and Transarterial Chemoembolization

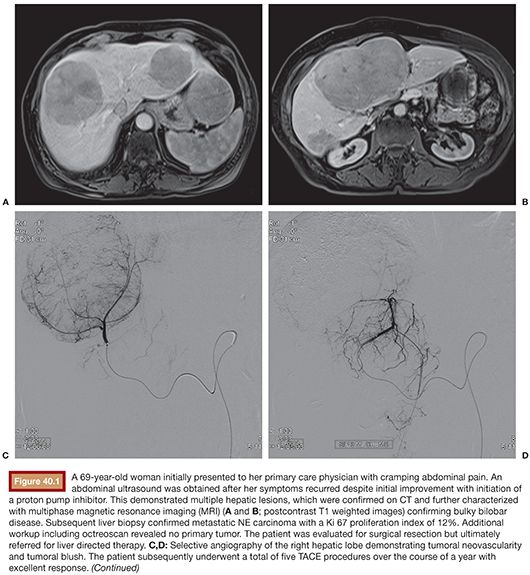

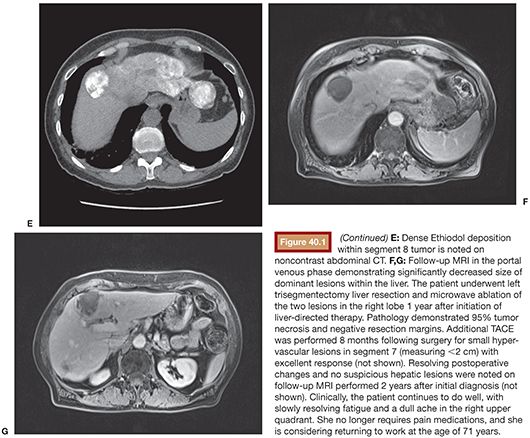

First proven in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma, bland embolization and chemoembolization are gaining traction as palliative treatment of NLMs, particularly in cases of high metastatic tumor burden in the liver. Occasionally, patients are successfully rendered surgically resectable following this type of liver-directed therapy (Fig. 40.1). Administration of embolic material via the hepatic artery, with or without coadministration of chemotherapy, has shown generally high response rates both in tumor control and symptom palliation. Although it is known that chemotherapy accumulates up to a 20-fold greater concentration when coadministered with an embolic agent,1 the choice of TAE versus TACE in this setting remains controversial.31

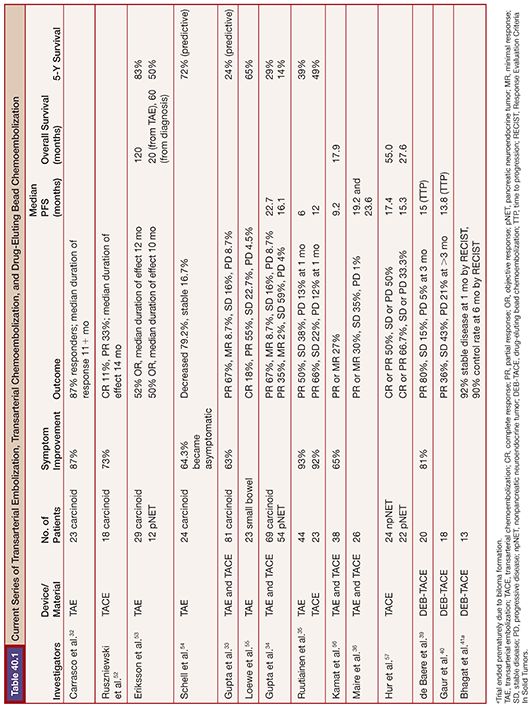

TAE and TACE have been studied in NLMs for over three decades (Table 40.1). Carrasco et al.32 treated 25 patients with carcinoid syndrome using TAE consisting of Ivalon particles (Unipoint Industries, High Point, North Carolina) delivered from the main hepatic artery or a branch vessel, taking care to maintain vessel patency to allow for repeat embolization procedures; a total of 79 embolizations were performed. Symptom improvement was dramatic among 20 of the 23 patients who were followed, with over two-thirds reporting excellent symptom control and a median response duration of 20 months. Among 52 patients with carcinoid tumors treated with either TAE or TACE, 63% had an improvement in symptoms in a study by Gupta et al.33 Carcinoid crisis was observed following 12.3% of procedures, which was managed in part with octreotide.

In contrast, in a study of 69 patients with metastatic carcinoid, patients treated with TAE were actually six times more likely to respond radiographically than those treated with TACE (81% vs. 44.4%; P = .002); however, overall survival was similar between the two treatments.34 Given the relative resistance of carcinoid tumors to systemic chemotherapy, this result is not necessarily unexpected. In contrast, patients with islet cell tumors showed a trend toward improved response (50% vs. 25%) and prolonged survival (31.5 months vs. 18.2 months) with TACE compared to TAE, but the differences were not statistically significant. Ruutiainen et al.35 reviewed the results of 219 embolizations in 67 patients with NLMs.35 Twenty-three patients had TAE, whereas 44 patients had triple drug TACE. Overall, 30-day mortality was 1.4%, with no difference in grade 3 or greater toxicity or hospital stay (1.5 days) between the two groups. Mean duration of symptom control was 15 months for TACE and 7.5 months for TAE. There was no significant difference in survival between the two groups.

A small prospective randomized study was recently published by Maire et al.36 Twenty-six patients with unresectable NLM were randomized to TAE versus TACE. Two-year PFS was not significantly different (38% TACE, 44% TAE), with no significant difference in 2-year overall survival. An extensive review comparing TAE and TACE for treatment of metastatic carcinoid and islet cell carcinomas concluded that the therapeutic advantage of adding chemotherapy to the embolization regimen is questionable and that the regimens vary widely in the literature such that a consensus on ideal chemotherapy has not been established.31

Transarterial Chemoembolization with Drug-Eluting Beads

Although coadministration of chemotherapy with an embolic agent effectively increases drug concentration within liver metastases, the pharmacokinetics are variable and not optimized. Drug-eluting beads (DEBs) are a relatively new local drug delivery platform that can allow for much slower and reproducible drug release. In vitro study of an emulsion of doxorubicin and Lipiodol demonstrated complete release of the chemotherapeutic agent within 4 hours, whereas only 15% of the doxorubicin eluded from 100- to 300-mm DC beads in 24 hours.37 Theoretically, DEBs can therefore maximize drug delivery to hepatic metastases and minimize systemic toxicity. Plasma levels of circulating chemotherapy are diminished up to 70% to 85% with use of DEBs versus conventional TACE in a rabbit hypervascular tumor model.38

Initial experience with DEB-TACE in NETs has shown high response rates, but there are concerns regarding increased incidence of biliary toxicity. de Baere et al.39 treated 20 patients with well-differentiated gastroenteropancreatic tumors with DEBs (500 to 700 mm) loaded with doxorubicin. After 3 months, partial response was seen in 16 of 20 patients (80%), and only 1 patient (5%) had progressive disease. Mean time to progression was 15 months. Five patients (25%) developed subsegmental regions of liver necrosis identified on follow-up computed tomography (CT) scans located peripheral to the tumors targeted for embolization. In another study of 18 patients with metastatic NETs, an objective response was observed in 17 of 26 (65%) procedures at intermediate-term (>3 months) follow-up.40 Two patients developed biliary injuries, one of whom required placement of a percutaneous internal/external biliary drainage catheter and the other noted incidentally on routine follow-up imaging and did not require additional treatment. In a more recent study of 13 patients with metastatic NETs, an objective response rate of 78% was observed in the targeted lesions; however, 7 patients (54%) developed bilomas following DEB-TACE (100- to 300-µm beads loaded with doxorubicin).41 Four of them required percutaneous drainage.

Guiu et al.,42 expanding on the initial report by de Baere et al.,39 analyzed 278 patients with NETs who underwent either conventional TACE (n = 152) or DEB-TACE (n = 126), compared to patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who underwent conventional TACE (n = 142) or DEB-TACE (n = 56). Liver/biliary injuries were defined as either a dilated bile duct, portal vein narrowing or thrombosis, or a biloma/liver infarct (grouped together given the difficulty in discriminating between these two entities at contrast-enhanced CT). Liver/biliary injuries occurred with a frequency of 35.7% for NET and 30.4% for HCC after DEB-TACE sessions, whereas frequencies of 7.2% and 4.2% were observed following conventional TACE for treatment of NET and HCC, respectively. On multivariate analysis, the risk of liver/biliary injury was 6.63 times greater with DEB-TACE than with conventional TACE.

Radioembolization

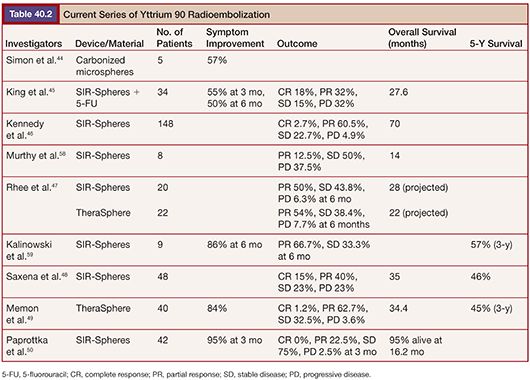

External beam radiation therapy has a limited role in the treatment of hepatic metastases due to the sensitivity of normal hepatic parenchyma relative to the doses required to treat metastatic lesions. However, use of a microsphere platform to deliver localized radiotherapy has been used with success in HCC and has subsequently been used to treat hepatic metastases.43 Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) consists of yttrium 90 (90Y) microspheres delivered via the hepatic artery typically to a target dose of 120 Gy. 90Y is a pure β emitter with a tissue penetration of approximately 2.5 mm. Similar to the preferential uptake of Lipiodol emulsions with TACE procedures, hypervascular NE metastases preferentially accumulate 90Y microspheres relative to normal liver parenchyma. Two devices are currently available: glass microspheres (TheraSphere; Nordion, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) and resin microspheres (SIR-Spheres; SIRTeX Medical Limited, New South Wales, Australia). Several trials have investigated their use for NLMs (Table 40.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree