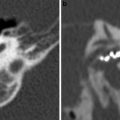

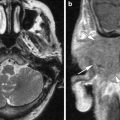

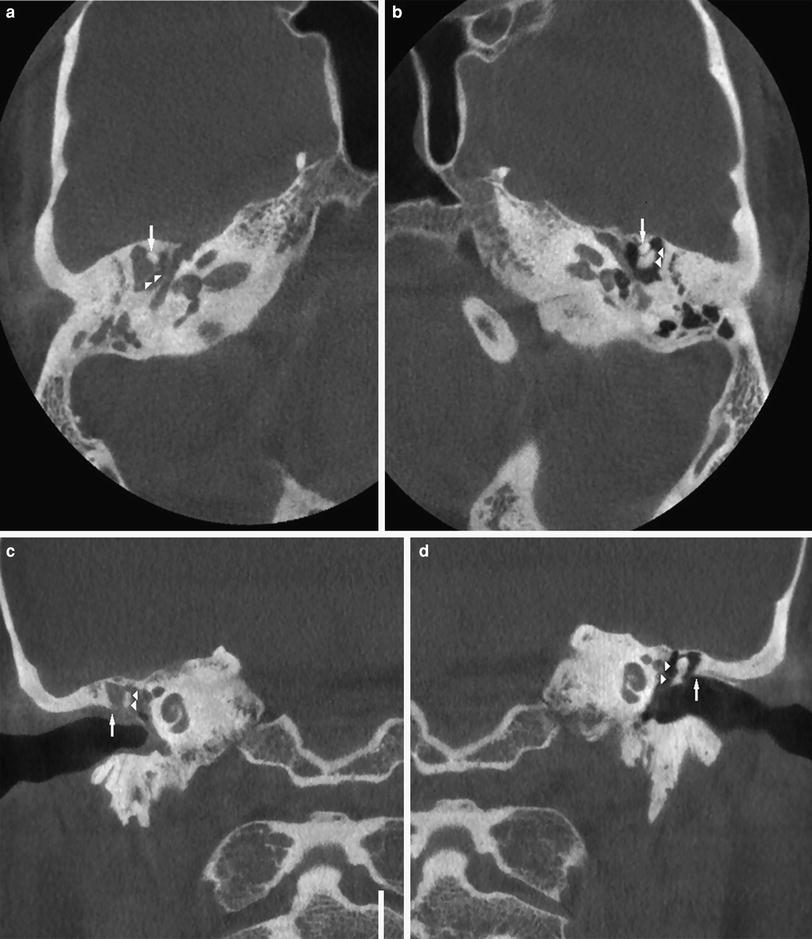

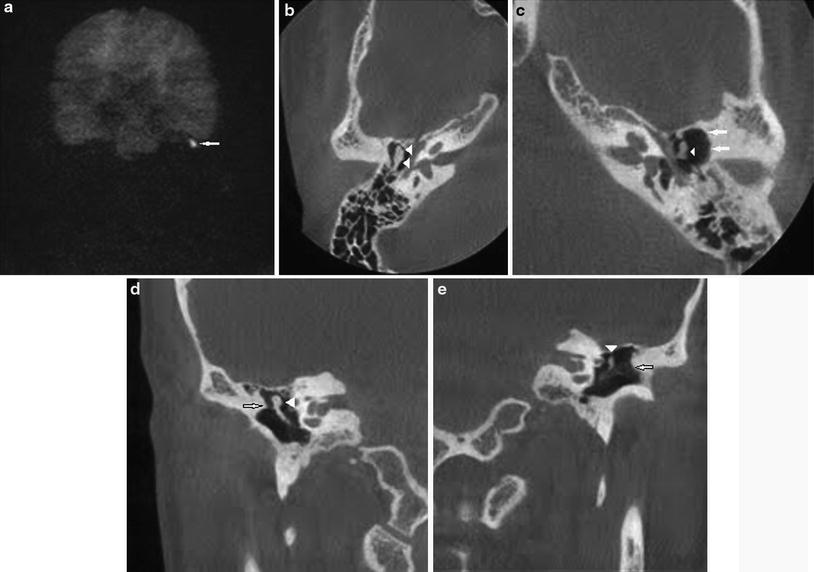

Fig. 1

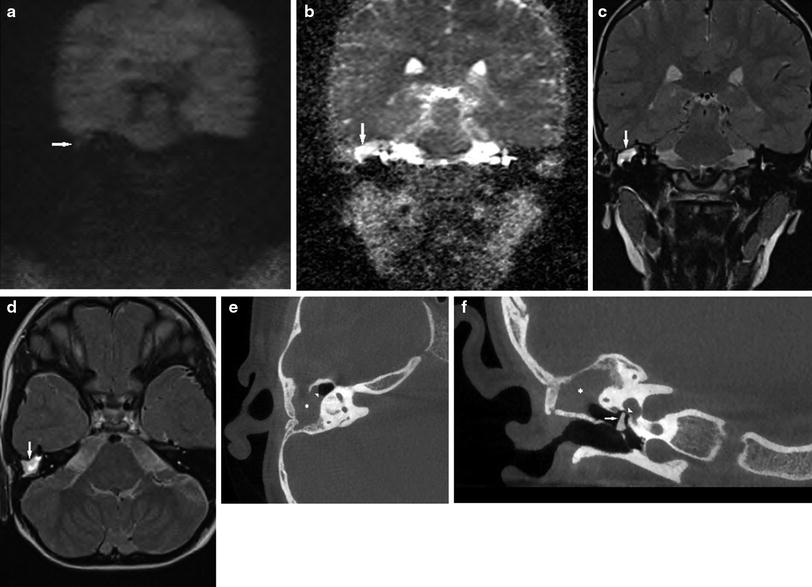

A 41-year-old-female investigated for conductive hearing loss on the left side. At otoscopy, an intact tympanic membrane was found with suspicion of a whitisch lesion behind it. b1000 HASTE diffusion-weighted sequence confirmed the presence of a congenital cholesteatoma. CBCT located the lesion and showed the erosive effect of the cholesteatoma on the ossicular chain. At surgery, the bony delineation over the second segment of the facial nerve canal was eroded. a Double oblique CBCT reformation through the plane of stapes and footplate on the right side (same level as Fig. 1b) demonstrating a normal footplate and a normal aspect and alignment of the tip of incus long process, capitellum and stapes crurae (arrow). b Double oblique CBCT reformation through the plane of stapes and footplate on the left side. There is a nodular soft tissue lesion (arrow) with loss of delineation of incus long process, capitellum and crurae of the stapes (compare to normal findings on the right side in Fig. 1a). c Coronal CBCT reformation at the level of the oval window (same level as Fig. 1d). In front of the oval window, the capitellum can be noted (arrow). Note the bony delineation over the second segment of the facial nerve running underneath the lateral semicircular canal (arrowhead). d Coronal CBCT reformation at the level of the oval window. Large semi-lunar soft tissue nodule in the mesotympanon (arrow). Note the loss of delineation of the capitellum (compare to the normal findings in Fig. 1c). The lesion is also abutting the second segment of the facial nerve (arrowhead). e Coronal b1000 HASTE diffusion-weighted image clearly demonstrates the nodular high signal intensity of the lesion, compatible with a congenital cholesteatoma (arrow)

By definition, a congenital cholesteatoma is found behind an intact tympanic membrane without any signs of infection (Baràth et al. 2011; De Foer et al. 2010a; Nelson et al. 2002; Darrouzet et al. 2002).

Middle ear congenital cholesteatoma represent approximately 2 % of all middle ear cholesteatomas (Baràth et al. 2011). In the paediatric population, the number of congenital cholesteatomas in the overall paediatric cholesteatoma population is higher, reaching 16 % (Darrouzet et al. 2002).

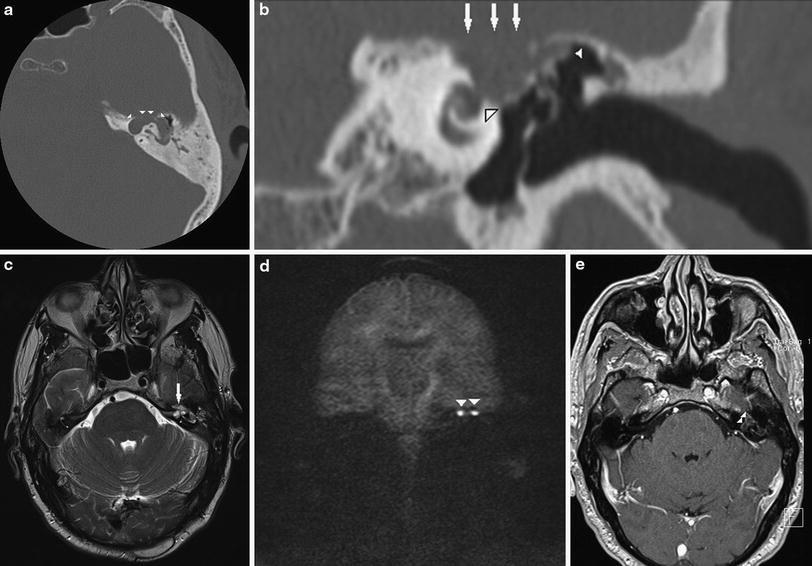

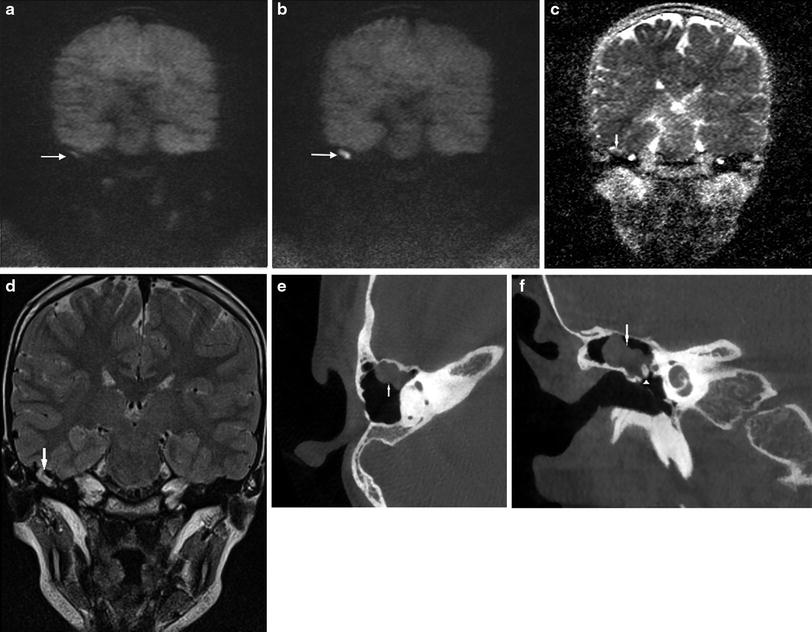

Congenital cholesteatoma can also be situated in the petrous bone near the otic capsule (Fig. 2). In those cases, it is very often found near the geniculate ganglion in which it can have a component protruding in the middle ear as well as an inner ear component (De Foer et al. 2010a). The middle ear component can give rise to conductive hearing loss, the inner ear component around the geniculate ganglion can give rise to a progressive facial nerve palsy. Care should be taken that at surgery both components of the congenital cholesteatoma are resected as any residual cholesteatoma in the inner ear may continue to grow. Usually, these patients are young.

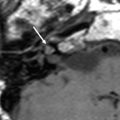

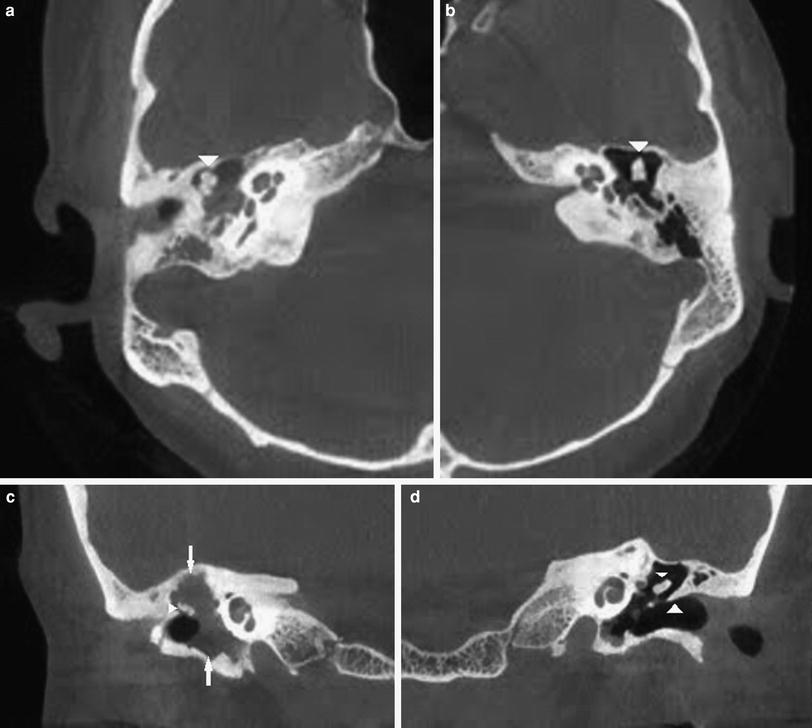

Fig. 2

A 51-year-old male with a long-standing history of mixed hearing loss on the left side and a sudden onset of facial nerve paralysis on the left side (House–Brackmann grade III). The sharply delineated punched-out lesion on CT in the left petrous bone apex, near the region of the geniculate ganglion with invasion in the membranous labyrinth, is higly suspicious of a congenital cholesteatoma. The lesion probably had a large middle ear component which was partially evacuated through the tympanic membrane into the external auditory canal. MR findings confirm the presence of a congenital cholesteatoma as the lesion displays a clear hyper-intense signal on b1000 diffusion-weighted images. a Axial CT image at the level of the superior semicircular canal on the left side. A sharply delineated semi-lunar punched-out soft tissue lesion (arrowheads) anteriorly located in the petrous bone apex around the anterior limb of the superior semicircular canal can be noted. b Coronal CT image at the level of the geniculate ganglion and cochlea. Note the large sharply delineated punched-out soft tissue lesion in the region of the geniculate ganglion (arrows). The lesion is abutting the cochlea (large arrowhead). There is a small component of soft tissues extending in the middle ear attic (small arrowhead). The delineation of the ossicles is lost due to erosion and subsequent partial evacuation of the middle ear component of the congenital cholesteatoma. c Axial TSE T2-weighted image at the level of the membranous labyrinth on the left side. There is small moderate intense nodular lesion anterior in the petrous bone apex (arrow). d Coronal b1000 HASTE diffusion-weighted image (same level as Fig. 2b). Bilobular hyper-intense lesion, underneath the tegmen (arrowheads), pathognomonic for a congenital cholesteatoma. e Axial T1-weighted image 45 min after intravenous administration of gadolinium-DTPA. Anterior and medial in the petrous bone apex, a bilobular peripherally enhancing low intense lesion is noted (arrowheads). The lesion displays signal characteristics and enhancement pattern of a cholesteatoma

It should be noted that congenital cholesteatoma can be found anywhere around the structures of the membranous labyrinth. When situated around the structures of the inner ear, profound sensorineural hearing loss can be found.

4.3 Clinical Signs

The clinical presentation of a congenital middle ear cholesteatoma may be an asymptomatic white mass behind an intact tympanic membrane, usually discovered incidentally in the course of the evaluation of conductive hearing loss (Baràth et al. 2011; De Foer et al. 2010a; Nelson et al. 2002; Darrouzet et al. 2002). In advanced stages, congenital cholesteatoma may cause the same symptoms as the acquired one (Baràth et al. 2011; De Foer et al. 2010a) (see below).

In case of a congenital cholesteatoma situated in or near the otic capsule, sensorineural hearing loss is usually found. Association to facial nerve palsy can be found in case of extension to the geniculate ganglion region (De Foer et al. 2010a).

4.4 Treatment

The treatment of congenital cholesteatoma is almost always surgery. Depending on its location, surgery can be extremely difficult with considerable postoperative morbidity due to temporary balance disturbances and definite sensorineural hearing loss in case of invasion of the membranous labyrinth.

In case of a middle ear location, reconstructive surgery of the ossicular chain is very often required. Most frequently, closed techniques are used (De Foer et al. 2010a; Nelson et al. 2002; Darrouzet et al. 2002) (see below).

If the congenital cholesteatoma is located near the geniculate ganglion, care should be taken to remove the entire congenital cholesteatoma as retained parts of the congenital cholesteatoma—mainly the inner ear components—may continue to grow.

4.5 Imaging

In the particular setting of a young patient presenting with conductive hearing loss and a whitish lesion at otoscopy behind an intact tympanic membrane, CT scan will nicely demonstrate the cholesteatoma as a usually rather small nodular soft tissue lesion in the anterosuperior part of the middle ear. It will also show the relationship to the ossicles and eventual ossicular erosion (Fig. 1) (Baràth et al. 2011; De Foer et al. 2010a).

Discussion still remains whether cone beam CT or CT should be used to evaluate middle ear structures and whether cone beam CT should be used to perform cholesteatoma evaluation on CT. The role of cone beam CT seems however to be increasing. It should be noted also that radiation dose in CBCT of temporal bones is substantially lower than that of CT (own unpublished data).

In case of a location in the inner ear or membranous labyrinth, the congenital cholesteatoma presents itself as a sharply delineated punched-out lesion in the temporal bone pyramid abutting or involving the structures of the membranous labyrinth. As already mentioned, the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve is very often involved (Fig. 2).

Very often, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is required to evaluate the involvement of the membranous labyrinth. On non-echo planar (EP) diffusion-weighted (DW) sequences, the congenital cholesteatoma will demonstrate as a clear—usually nodular—hyper-intensity on b1000 images (Figs. 1, 2). On ADC maps, the congenital cholesteatoma displays low signal intensity due to diffusion restriction. On T2-weighted images, the lesion shows a moderate hyper-intensity. Intensity on T1-weighted images is low, with possibly some peripheral enhancement after intravenous administration of gadolinium (Fig. 2).

Differential diagnosis should be made with other lytic temporal bone lesions. Metastatic lesions can be found anywhere in the temporal bone but usually involve a different age group of patients. These lesions are almost always ill-defined contrary to the sharply delineated punched-out lesions of the congenital cholesteatoma. The glomus jugulo-tympanicum has an entirely different clinical presentation, very often with pulsatile tinnitus. At otoscopy, a blueish lesion can be found behind an intact tympanic membrane. Moreover the lesion is invariably centred over the jugular foramen, with—contrary to the congenital cholesteatoma—ill-defined borders (De Foer et al. 2010a).

5 The Acquired Cholesteatoma

5.1 Introduction: Etiopathogenesis

There are many theories regarding the etiopathogenic mechanism of acquired cholesteatoma. The ‘retraction pocket theory’ is the generally most accepted one.

In this theory, the acquired cholesteatoma is regarded as a type of chronic middle ear infection. Together with poor ventilation of the middle ear and mastoid—due to Eustachian tube dysfunction—this leads to an increased negative pressure in the tympanic cavity, resulting in retraction of the tympanic membrane with invagination of a part of it in the middle ear (Baràth et al. 2011).

5.2 Location

There are two different subtypes of cholesteatoma depending on the location of origin of the cholesteatoma, the pars flaccida cholesteatoma and the pars tensa cholesteatoma.

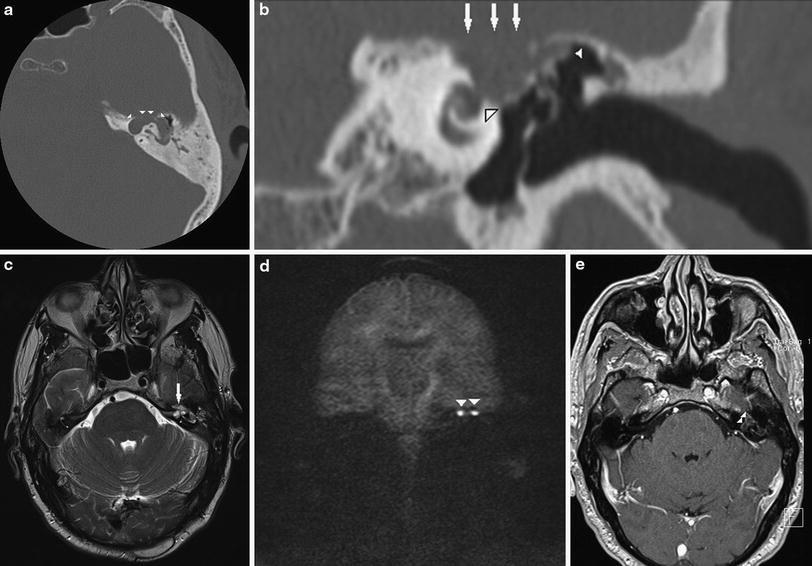

Most frequently, these retraction pockets are situated at the upper part of the tympanic membrane, the so-called pars flaccida (Baràth et al. 2011; De Foer et al. 2010a; Lemmerling and De Foer 2001). Pars flaccida retraction pockets expand into the lateral epitympanic recess, the so-called Prusack’s space. By gradually exfoliating, the retraction pocket enlarges and will start to erode surrounding structures. It can erode the malleus head, incus body and lateral epitympanic wall (Fig. 3). If the lesion grows further, it will start to fill up the attic with possible further erosion of the tegmen of the middle ear, the bony delineation of the tympanic segment of the facial nerve and the lateral semicircular canal (Baràth et al. 2011; De Foer et al. 2010a; Lemmerling and De Foer 2001). By doing so, the cholesteatoma may invade the middle cranial fossa or the membranous labyrinth. In case of membranous labyrinth invasion, it is usually the surrounding inflammation that is invading the membranous labyrinth and not the cholesteatoma as such (Baràth et al. 2011; De Foer et al. 2010a; Lemmerling and De Foer 2001).

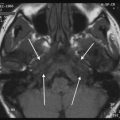

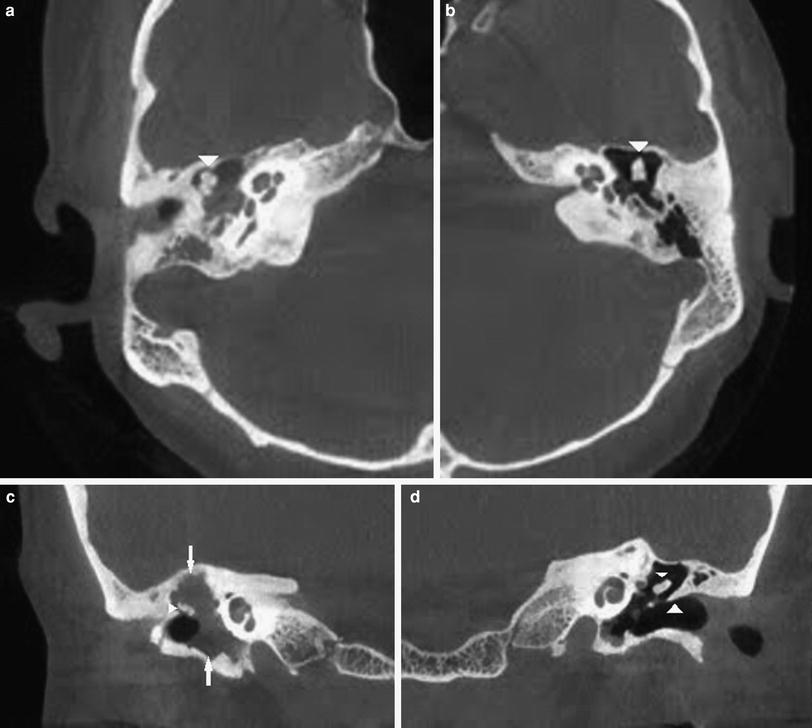

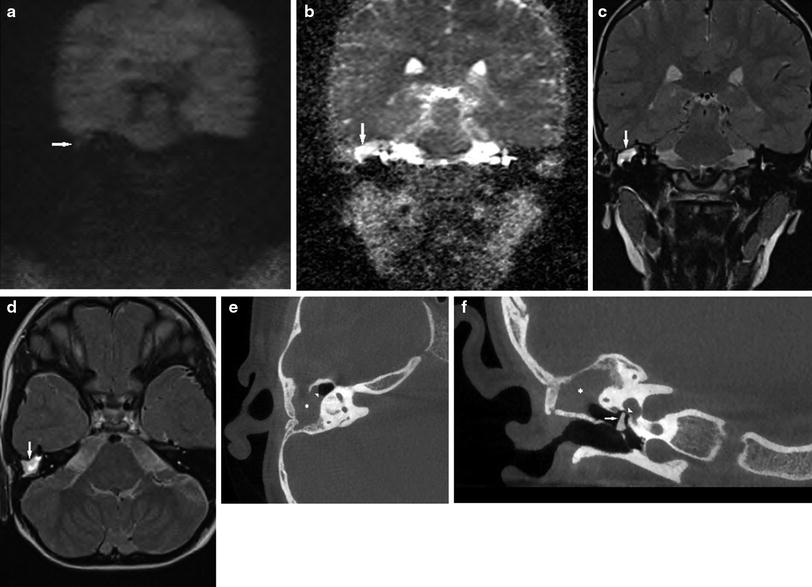

Fig. 3

A 24-year-old male with a history of chronic ear discharge on the right side and with suspicion of a retraction pocket at otoscopy. Pathognomonic image at CBCT of a pars flaccida cholesteatoma presenting itself as a soft tissue opacification in Prussak’s space with clear erosion of incus body and short process. a Axial CBCT image on the right side at the level of the second segment of the facial nerve. Note the complete opacification of the poorly aerated middle ear. There is almost complete erosion of the incus body and short process (arrowheads). Note the intact appearance of the malleus head (arrow). Compare to the normal left side in Fig. 3b. b Axial CBCT image on the left side at the level of the second segment of the facial nerve (same level as Fig. 3a). Again, there is a poorly aerated middle ear. There is a normal delineation of the malleus head (arrow) and incus body (arrowheads). The incus short process cannot be delineated on this image due to partial volume effect. c Coronal CBCT image on the right side at the level of the cochlea. Note the opacification of the meso- and epitympanon with erosion of the scutum (arrow). The complex of malleus head and incus body—compare to the normal side in Fig. 3d—looks thinned and eroded (arrowheads). d Coronal CBCT image on the left side at the level of the cochlea (same level as Fig. 3c). There is a complete aeration of the middle ear with completely intact delineation of the complex malleus and incus body (arrowheads). Note the intact delineation of the scutum (arrow) and the aerated Prussak’s space

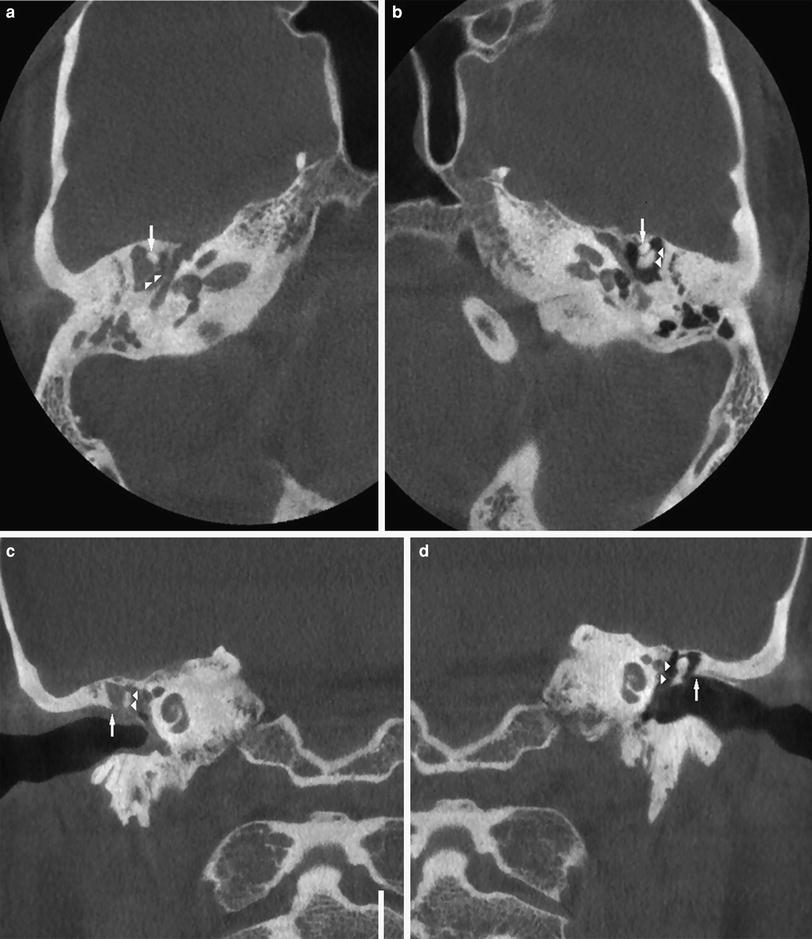

If the retraction pocket originates at the posterior-inferior part of the tympanic membrane—the so-called pars tensa—the cholesteatoma will expand around the long apophysis of the incus with extension medially to the ossicles (Fig. 4). This type of cholesteatoma is also called the sinus cholesteatoma. Contrary to the pars flaccida cholesteatoma, the pars tensa cholesteatoma grows from the lower part of the mesotympanon upwards and will displace the ossicles laterally. The pars tensa cholesteatoma is much less frequent than the pars flaccida cholesteatoma.

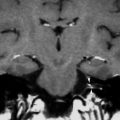

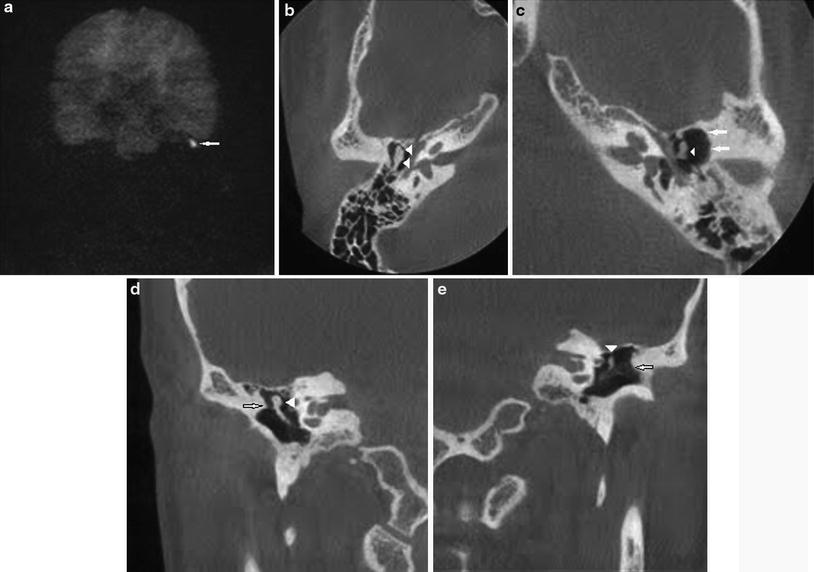

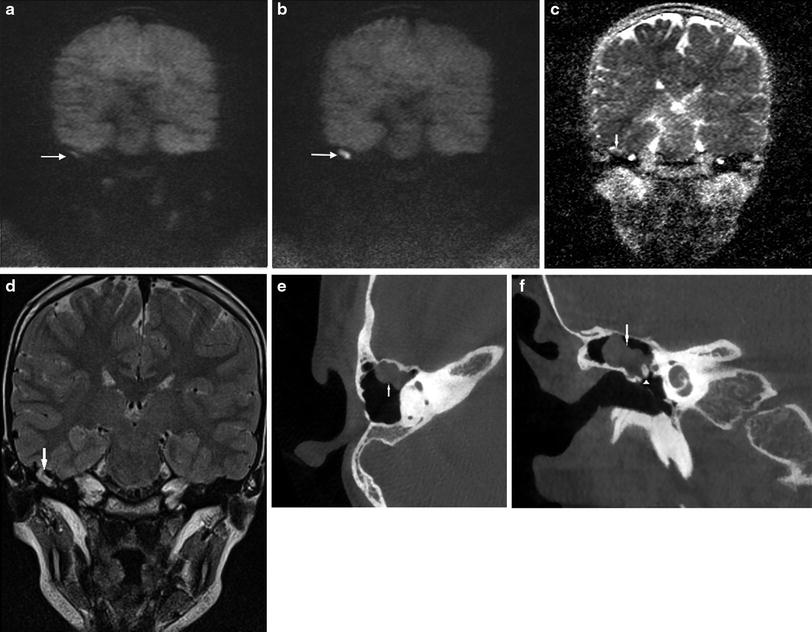

Fig. 4

An 18-year-old woman with a conductive hearing loss on the right side and a whitish lesion behind the pars tensa of an intact tympanic membrane. Findings on this CBCT examination are typical for a pars tensa cholesteatoma with ossicular erosion and lateral displacement of the ossicles. a Axial CBCT image at the level of the oval window. There is complete opacification of the middle ear with an intact delineation of the malleus and incus (arrowhead). Malleus and incus look displaced laterally (compare to the normal side, Fig. 4b). b Axial CBCT image at the level of the oval window (same level as Fig. 4a). The middle ear is completely aerated with a normal delineation of the ossicular chain (arrowhead). c Coronal CBCT image at the level of the cochlea. There is complete opacification of the middle ear, antrum and mastoid (arrows). The incus corpus seems to be slightly eroded (small arrowhead) with lateral displacement of the ossicules (compare to the normal situation on the left side in Fig. 4d). d Coronal CBCT image at the level of the cochlea. The middle ear and mastoid are completely aerated. There is a normal delineation of the ossicular chain (small arrowhead) and scutum (large arrowhead). Compare to Fig. 4c to evaluate the position of the ossicles

5.3 Clinical Signs

Patients with acquired cholesteatoma have a history of recurrent ear disease, Eustachian tube dysfunction, atelectasis of the middle ear and reduced pneumatisation of the mastoid. They usually have a long-standing history of chronic middle ear infection. At otoscopy, an intact or perforated tympanic membrane can be found. The cholesteatoma presents itself as a whitish, pearly soft tissue mass on or behind the tympanic membrane. Very often the clinician will be unable to exactly evaluate the extent of the cholesteatoma.

Special attention should be paid to the entity of the ‘empty cholesteatoma’—also called mural cholesteatoma. In these particular cases, the content of the cholesteatoma has evacuated itself—either by auto-evacuation either by suction cleaning—via the external auditory canal. The cholesteatoma epithelium however is still adherent to the walls of the middle ear and mastoid (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

A 42-year-old male with a clinically and otoscopically known middle ear cholesteatoma on the left side. HASTE diffusion-weighted image clearly demonstrates a high signal intensity on the left side, pathognomic for a middle ear cholesteatoma. However, CBCT performed 4 months later—prior to surgery—shows no clear soft tissue density in the left middle ear and/or mastoid. However, the indirect signs of cholesteatoma—e.g. ossicular erosion—are still present. It was concluded that the cholesteatoma had been evacuated in the time period elapsed between the MRI and CBCT examination probably due to auto evacuation of the cholesteatoma. The content of the cholesteatoma sac was evacuated but the cholesteatoma matrix is still adherent to the walls of the middle ear. a Coronal b1000 HASTE diffusion-weighted sequence clearly demonstrates a nodular hyper-intensity on the left side pathognomonic of middle ear cholesteatoma (arrow). b Axial CBCT image at the level of the second segment of the facial nerve on the right side. There is a normal delineation of the ossicular chain (arrowheads) without any associated soft tissues. Note the higher density of the ossicles when compared with the demineralised aspect of the ossicles on the left side (see Fig. 5c). c Axial CBCT image at the level of the second segment of the facial nerve on the left side. Compared to the normal side in Fig. 5b, the lateral epitympanic wall seems to be eroded (arrows) and the incus body also seems to be eroded (arrowhead). Note that the residual ossicular chain looks also demineralised compared to the normal right side in Fig. 5b. Clear nodular soft tissues cannot be found. d Coronal CBCT image at the level of the internal auditory canal on the right side. There is a normal delineation of the ossicular chain (arrowhead) without any associated soft tissues. Note that Prussak’s space is free and that the scutum is sharp (arrow). e Coronal CBCT image at the level of the internal auditory canal on the left side. There are no clear associated soft tissues. The scutum looks amputated (arrow), with an eroded ossicular chain (arrowhead) looking also demineralised. Compare to the normal side in Fig. 5d

Middle ear cholesteatoma may present with the following clinical signs (Baràth et al. 2011; De Foer et al. 2010a; Lemmerling and De Foer 2001).

Chronic ear discharge of the ear is one of the most frequent complaints. Some form of hearing loss is found in the majority of patients, ranging from 60 to 80 %. The hearing loss can be conductive or mixed. Less frequently, sensorineural hearing loss is found. Patients may also present with a dead ear (Baràth et al. 2011; De Foer et al. 2010a; Lemmerling and De Foer 2001). Facial paralysis occurs rarely with middle ear cholesteatomas. Only in extensive cases, the bony delineation of the facial nerve canal may become eroded with subsequent paralysis. Sudden vertigo can be seen in cases with erosion of the lateral semicircular canal and membranous labyrinth invasion.

5.4 Treatment

Treatment of the acquired cholesteatoma is in most cases performed by surgery.

Different surgical approaches exist.

In the canal wall down (CWD) approach or radical mastoidectomy, the mastoid is opened, the wall of the external auditory canal is removed with total eradication of pathology. The large postoperative cavity enables a good control and inspection for the surgeon but has major drawbacks for the patient. The patient is for example no longer allowed to swim as contact of the water with the exposed lateral semicircular canal may give rise to a sudden onset of vertigo (Lemmerling and De Foer 2001).

Most frequently however, the canal wall up (CWU) procedure is used. In this type of procedure, the wall of the external auditory canal is preserved, the mastoid is opened and the pathology is eradicated. At the same time, a tympanic membrane graft and/or ossicular chain reconstruction can be performed. However, sometimes the reconstruction of the ossicular chain needs to be performed during a second-look procedure (De Foer et al. 2010a; Lemmerling and De Foer 2001; Brown 1982) (Figs. 6, 7).

Fig. 6

An 8-year-old girl with a prior history of surgery for an attical cholesteatoma on the right side, treated by CWU tympanoplasty. This case illustrates the current state-of-the-art way of working in cholesteatoma follow-up. The first MRI follow-up examination displayed a doubtful high signal intensity on b1000 HASTE diffusion-weighted images which became a clear nodular high signal intensity on MRI follow-up. CT scan—in this case CBCT, resulting in a substantially lower radiation dose—is reserved for the pre-operative setting. a Coronal b1000 HASTE diffusion-weighted image 1 year after first-stage surgery demonstrates a doubtful high signal intensity (arrow) in the right temporal bone, underneath the tegmen. Based upon this image, diagnosis of a cholesteatoma cannot be confirmed. MRI follow-up examination after 1 year was advised. b Coronal b1000 HASTE diffusion-weighted image acquired 1 year after Fig. 1a showing a clear bilobular nodular high signal intensity (arrow) compatible with a large residual cholesteatoma. c Corresponding ADC map, same level as Fig. 6a and b. The cholesteatoma corresponds to a nodular zone of clear signal drop (arrow). d Corresponding coronal TSE T2-weighted image, same level as Fig. 6a, b and c. The cholesteatoma corresponds to a bilobular nodular moderate intense lesion under the tegmen on the right side (arrow). e Axial CBCT image—performed in a preoperative setting—through the superior semicircular canal. The cholesteatoma is seen as a bilobular nodular soft tissue lesion (arrow), located anterior in the mastoidectomy cavity. f Coronal CBCT image—performed in a preoperative setting—at the level of the cochlea. Large nodular soft tissue lesion, anterior in the canal-wall-up tympanoplasty cavity (arrow), partially situated around the malleus head (arrowhead): residual cholesteatoma. Note the persistent delineation of the external auditory canal typical for a CWU tympanoplasty

Fig. 7

A 6-year-old boy with a history of cholesteatoma surgery 1 year prior on the right side. The shortened MRI protocol (b0, b1000 HASTE diffusion, coronal and axial TSE T2-weighted images) excludes the presence of a cholesteatoma. CBCT was performed prior to surgery in order to correct the malpositioned ossicular reconstruction. a Coronal b1000 HASTE diffusion-weighted image. On the right side, there is an isointense lesion underneath the tegmen (arrow). The low signal intensity excludes the presence of a cholesteatoma. b Corresponding ADC map (same level as Fig. 7a). On the right side, there is a persisting hyper-intense signal on ADC map, confirming the absence of cholesteatoma (arrow). c Coronal TSE T2-weighted image at the level of the cochlea (same level as Fig. 7a and b). There is a clear hyper-intensity on the right side (arrow). Signal intensity is by far too high to be compatible with a cholesteatoma. The resection cavity is filled with post-operative tissue. d Axial TSE T2-weighted image at the level of the superior semicircular canal. Again a clear hyper-intensity on the right side is noted (arrow). Signal intensity is again too high to be compatible with a cholesteatoma. e Axial CBCT image on the right side at the level of the superior semicircular canal. There is a subtotal opacification (asterisk) of the resection cavity with a posterior convex delineation (arrowhead). The subtotal opacification on CBCT cannot be differentiated. f Coronal CBCT image on the right side at the level of the oval window. Note again the homogeneous opacification (asterisk) of the resection cavity. Again the soft tissue opacification cannot be differentiated. There is an ossicular reconstruction based on a remodelled incus (arrow). The remodelled incus is not abutting the oval window (arrowhead). Surgical reintervention is hence mandatory. Note again the intact delineation of the roof of the external auditory canal compatible with a CWU tympanoplasty technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree